Causes of the 2007–2012 global financial crisis: Difference between revisions

→References: add to Category:Late 2000s global financial crisis; add section "See also". |

→Notable quotations on the causes and nature of the crisis: rm cherry picked quote, out of hundreds of thousand regarding the subprime crisis who gets to pick these three massive POV violation |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

While the housing and credit bubbles built, a series of factors caused the financial system to both expand and become increasingly fragile. Policymakers did not recognize the increasingly important role played by financial institutions such as [[investment banks]] and [[hedge funds]], also known as the [[shadow banking system]]. Some experts believe these institutions had become as important as commercial (depository) banks in providing credit to the U.S. economy, but they were not subject to the same regulations.<ref>[http://www.newyorkfed.org/newsevents/speeches/2008/tfg080609.html Geithner-Speech Reducing Systemic Risk in a Dynamic Financial System]</ref> These institutions as well as certain regulated banks had also assumed significant debt burdens while providing the loans described above and did not have a financial cushion sufficient to absorb large loan defaults or MBS losses.<ref>[http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/9c158a92-1a3c-11de-9f91-0000779fd2ac.html Greenspan-We Need a Better Cushion Against Risk]</ref> These losses impacted the ability of financial institutions to lend, slowing economic activity. Concerns regarding the stability of key financial institutions drove central banks to provide funds to encourage lending and restore faith in the [[commercial paper]] markets, which are integral to funding business operations. Governments also [[bailout|bailed out]] key financial institutions and implemented economic stimulus programs, assuming significant additional financial commitments. |

While the housing and credit bubbles built, a series of factors caused the financial system to both expand and become increasingly fragile. Policymakers did not recognize the increasingly important role played by financial institutions such as [[investment banks]] and [[hedge funds]], also known as the [[shadow banking system]]. Some experts believe these institutions had become as important as commercial (depository) banks in providing credit to the U.S. economy, but they were not subject to the same regulations.<ref>[http://www.newyorkfed.org/newsevents/speeches/2008/tfg080609.html Geithner-Speech Reducing Systemic Risk in a Dynamic Financial System]</ref> These institutions as well as certain regulated banks had also assumed significant debt burdens while providing the loans described above and did not have a financial cushion sufficient to absorb large loan defaults or MBS losses.<ref>[http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/9c158a92-1a3c-11de-9f91-0000779fd2ac.html Greenspan-We Need a Better Cushion Against Risk]</ref> These losses impacted the ability of financial institutions to lend, slowing economic activity. Concerns regarding the stability of key financial institutions drove central banks to provide funds to encourage lending and restore faith in the [[commercial paper]] markets, which are integral to funding business operations. Governments also [[bailout|bailed out]] key financial institutions and implemented economic stimulus programs, assuming significant additional financial commitments. |

||

==Notable quotations on the causes and nature of the crisis== |

|||

Fed Chairman [[Ben Bernanke]] summarized the crisis as follows during a January 2009 speech: |

|||

<blockquote> |

|||

For almost a year and a half the global financial system has been under extraordinary stress—stress that has now decisively spilled over to the global economy more broadly. The proximate cause of the crisis was the turn of the housing cycle in the United States and the associated rise in delinquencies on subprime mortgages, which imposed substantial losses on many financial institutions and shook investor confidence in credit markets. However, although the subprime debacle triggered the crisis, the developments in the U.S. mortgage market were only one aspect of a much larger and more encompassing credit boom whose impact transcended the mortgage market to affect many other forms of credit. Aspects of this broader credit boom included widespread declines in underwriting standards, breakdowns in lending oversight by investors and rating agencies, increased reliance on complex and opaque credit instruments that proved fragile under stress, and unusually low compensation for risk-taking. The abrupt end of the credit boom has had widespread financial and economic ramifications. Financial institutions have seen their capital depleted by losses and writedowns and their balance sheets clogged by complex credit products and other illiquid assets of uncertain value. Rising credit risks and intense risk aversion have pushed credit spreads to unprecedented levels, and markets for securitized assets, except for mortgage securities with government guarantees, have shut down. Heightened systemic risks, falling asset values, and tightening credit have in turn taken a heavy toll on business and consumer confidence and precipitated a sharp slowing in global economic activity. The damage, in terms of lost output, lost jobs, and lost wealth, is already substantial.<ref>[http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20090113a.htm Bernanke Speech - January 13 2009]</ref></blockquote> |

|||

In its "Declaration of the Summit on Financial Markets and the World Economy," dated 15 November 2008, leaders of the [[G-20 major economies|Group of 20]] cited the following causes: |

|||

{{quote|During a period of strong global growth, growing capital flows, and prolonged stability earlier this decade, market participants sought higher yields without an adequate appreciation of the risks and failed to exercise proper due diligence. At the same time, weak underwriting standards, unsound risk management practices, increasingly complex and opaque financial products, and consequent excessive leverage combined to create vulnerabilities in the system. Policy-makers, regulators and supervisors, in some advanced countries, did not adequately appreciate and address the risks building up in financial markets, keep pace with financial innovation, or take into account the systemic ramifications of domestic regulatory actions.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2008/11/20081115-1.html |title=Declaration of G20 |publisher=Whitehouse.gov |date= |accessdate=2009-02-27}}</ref>}} |

|||

[[Thomas Friedman]] summarized the causes of the crisis in November 2008: {{quote|Governments are having a problem arresting this deflationary downward spiral — maybe because this financial crisis combines four chemicals we have never seen combined to this degree before, and we don’t fully grasp how damaging their interactions have been, and may still be. Those chemicals are: 1) massive leverage — by everyone from consumers who bought houses for nothing down to hedge funds that were betting $30 for every $1 they had in cash; 2) a world economy that is so much more intertwined than people realized, which is exemplified by British police departments that are financially strapped today because they put their savings in online Icelandic banks — to get a little better yield — that have gone bust; 3) globally intertwined financial instruments that are so complex that most of the C.E.O.’s dealing with them did not and do not understand how they work — especially on the downside; 4) a financial crisis that started in America with our toxic mortgages. When a crisis starts in Mexico or Thailand, we can protect ourselves; when it starts in America, no one can. You put this much leverage together with this much global integration with this much complexity and start the crisis in America and you have a very explosive situation.<ref>[http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/16/opinion/16friedman.html?em NYT Friedman - We're Gonna Need a Bigger Boat]</ref>}} |

|||

U.S. President [[Barack Obama]] discussed the causes of the crisis in a June 2009 speech:<ref>[http://www.whitehouse.gov/the_press_office/Remarks-of-the-President-on-Regulatory-Reform/]</ref> |

|||

*"It is an indisputable fact that one of the most significant contributors to our economic downturn was a unraveling of major financial institutions and the lack of adequate regulatory structures to prevent abuse and excess. A culture of irresponsibility took root from Wall Street to Washington to Main Street. And a regulatory regime basically crafted in the wake of a 20th century economic crisis -- the Great Depression -- was overwhelmed by the speed, scope, and sophistication of a 21st century global economy." |

|||

*"Many Americans bought homes and borrowed money without being adequately informed of the terms, and often without accepting the responsibilities." |

|||

*"Meanwhile, executive compensation -- unmoored from long-term performance or even reality -- rewarded recklessness rather than responsibility." |

|||

*"There was far too much debt and not nearly enough capital in the system. And a growing economy bred complacency." |

|||

==Macroeconomic conditions== |

==Macroeconomic conditions== |

||

Revision as of 21:37, 14 July 2009

An editor has nominated this article for deletion. You are welcome to participate in the deletion discussion, which will decide whether or not to retain it. |

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

| Part of a series on the |

| Great Recession |

|---|

| Timeline |

Many factors directly and indirectly caused the ongoing Financial crisis of 2007-2009, also known as the Subprime mortgage crisis, with experts placing different weights upon particular causes. The complexity and interdependence of many of the causes, as well as competing political, economic and organizational interests, have resulted in a variety of narratives describing the crisis. One category of causes created a vulnerable or fragile financial system, including complex financial securities, a dependence on short-term funding markets, and international trade imbalances. Other causes increased the stress on this fragile system, such as high corporate and consumer debt levels. Still others represent shocks to that system, such as the ongoing foreclosure crisis and the failures of key financial institutions. Regulatory and market-based controls did not effectively protect this system or measure the buildup of risk. Some causes relate to particular markets, such as the stock market or housing market, while others relate to the global economy more broadly. A proper analysis of the root causes is helpful in managing the crisis and building a more stable financial system.[1]

A conventional summary of the causes

The immediate cause or trigger of the crisis was the bursting of the United States housing bubble which peaked in approximately 2005–2006.[2][3] High default rates on "subprime" and adjustable rate mortgages (ARM), began to increase quickly thereafter. An increase in loan incentives such as easy initial terms and a long-term trend of rising housing prices had encouraged borrowers to assume difficult mortgages in the belief they would be able to quickly refinance at more favorable terms. However, once interest rates began to rise and housing prices started to drop moderately in 2006–2007 in many parts of the U.S., refinancing became more difficult. Defaults and foreclosure activity increased dramatically as easy initial terms expired, home prices failed to go up as anticipated, and ARM interest rates reset higher. Falling prices also resulted in homes worth less than the mortgage loan, providing a financial incentive to enter foreclosure. The ongoing foreclosure epidemic that began in late 2006 in the U.S. continues to be a key factor in the global economic crisis, because it drains wealth from consumers and erodes the financial strength of banking institutions.

In the years leading up to the start of the crisis in 2007, significant amounts of foreign money flowed into the U.S. from fast-growing economies in Asia and oil-producing countries. This inflow of funds combined with low U.S. interest rates from 2002-2004 contributed to easy credit conditions, which fueled both housing and credit bubbles. Loans of various types (e.g., mortgage, credit card, and auto) were easy to obtain and consumers assumed an unprecedented debt load.[4][5] As part of the housing and credit booms, the amount of financial agreements called mortgage-backed securities (MBS), which derive their value from mortgage payments and housing prices, greatly increased. Such financial innovation enabled institutions and investors around the world to invest in the U.S. housing market. As housing prices declined, major global financial institutions that had borrowed and invested heavily in subprime MBS reported significant losses. Falling prices also resulted in homes worth less than the mortgage loan, providing a financial incentive to enter foreclosure. The ongoing foreclosure epidemic that began in late 2006 in the U.S. continues to drain wealth from consumers and erodes the financial strength of banking institutions. Defaults and losses on other loan types also increased significantly as the crisis expanded from the housing market to other parts of the economy. Total losses are estimated in the trillions of U.S. dollars globally.[6]

While the housing and credit bubbles built, a series of factors caused the financial system to both expand and become increasingly fragile. Policymakers did not recognize the increasingly important role played by financial institutions such as investment banks and hedge funds, also known as the shadow banking system. Some experts believe these institutions had become as important as commercial (depository) banks in providing credit to the U.S. economy, but they were not subject to the same regulations.[7] These institutions as well as certain regulated banks had also assumed significant debt burdens while providing the loans described above and did not have a financial cushion sufficient to absorb large loan defaults or MBS losses.[8] These losses impacted the ability of financial institutions to lend, slowing economic activity. Concerns regarding the stability of key financial institutions drove central banks to provide funds to encourage lending and restore faith in the commercial paper markets, which are integral to funding business operations. Governments also bailed out key financial institutions and implemented economic stimulus programs, assuming significant additional financial commitments.

Macroeconomic conditions

Two important factors that contributed to the United states housing bubble were low U.S. interest rates and a large U.S. trade deficit. Low interest rates made bank lending more profitable, while trade deficits resulted in large capital inflows to the U.S. Both made funds for borrowing plentiful and relatively inexpensive.

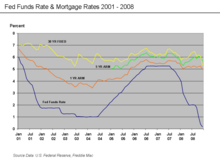

Interest rates

From 2000 to 2003, the Federal Reserve lowered the federal funds rate target from 6.5% to 1.0%.[9] This was done to soften the effects of the collapse of the dot-com bubble and of the September 2001 terrorist attacks, and to combat the perceived risk of deflation.[10] The Fed then raised the Fed funds rate significantly between July 2004 and July 2006.[11] This contributed to an increase in 1-year and 5-year adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM) rates, making ARM interest rate resets more expensive for homeowners.[12] This may have also contributed to the deflating of the housing bubble, as asset prices generally move inversely to interest rates and it became riskier to speculate in housing.[13][14]

Trade deficits

In 2005, Ben Bernanke addressed the implications of the USA's high and rising current account (trade) deficit, resulting from USA imports exceeding its exports.[15] Between 1996 and 2004, the USA current account deficit increased by $650 billion, from 1.5% to 5.8% of GDP. Financing these deficits required the USA to borrow large sums from abroad, much of it from countries running trade surpluses, mainly the emerging economies in Asia and oil-exporting nations. The balance of payments identity requires that a country (such as the USA) running a current account deficit also have a capital account (investment) surplus of the same amount. Hence large and growing amounts of foreign funds (capital) flowed into the USA to finance its imports. This created demand for various types of financial assets, raising the prices of those assets while lowering interest rates. Foreign investors had these funds to lend, either because they had very high personal savings rates (as high as 40% in China), or because of high oil prices. Bernanke referred to this as a "saving glut."[16] A "flood" of funds (capital or liquidity) reached the USA financial markets. Foreign governments supplied funds by purchasing USA Treasury bonds and thus avoided much of the direct impact of the crisis. USA households, on the other hand, used funds borrowed from foreigners to finance consumption or to bid up the prices of housing and financial assets. Financial institutions invested foreign funds in mortgage-backed securities. USA housing and financial assets dramatically declined in value after the housing bubble burst.[17][18]

Capital market pressures

Private capital and the search for yield

In a Peabody Award winning program, NPR correspondents argued that a "Giant Pool of Money" (represented by $70 trillion in worldwide fixed income investments) sought higher yields than those offered by U.S. Treasury bonds early in the decade, which were low due to low interest rates and trade deficits discussed above. Further, this pool of money had roughly doubled in size from 2000 to 2007, yet the supply of relatively safe, income generating investments had not grown as fast. Investment banks on Wall Street answered this demand with the mortgage-backed security (MBS) and collateralized debt obligation (CDO), which were assigned safe ratings by the credit rating agencies. In effect, Wall Street connected this pool of money to the mortgage market in the U.S., with enormous fees accruing to those throughout the mortgage supply chain, from the mortgage broker selling the loans, to small banks that funded the brokers, to the giant investment banks behind them. By approximately 2003, the supply of mortgages originated at traditional lending standards had been exhausted. However, continued strong demand for MBS and CDO began to drive down lending standards, as long as mortgages could still be sold along the supply chain. Eventually, this speculative bubble proved unsustainable.[19]

Housing market

The U.S. housing bubble and foreclosures

Between 1997 and 2006, the price of the typical American house increased by 124%.[20] During the two decades ending in 2001, the national median home price ranged from 2.9 to 3.1 times median household income. This ratio rose to 4.0 in 2004, and 4.6 in 2006.[21] This housing bubble resulted in quite a few homeowners refinancing their homes at lower interest rates, or financing consumer spending by taking out second mortgages secured by the price appreciation.

By September 2008, average U.S. housing prices had declined by over 20% from their mid-2006 peak.[22][23] Easy credit, and a belief that house prices would continue to appreciate, had encouraged many subprime borrowers to obtain adjustable-rate mortgages. These mortgages enticed borrowers with a below market interest rate for some predetermined period, followed by market interest rates for the remainder of the mortgage's term. Borrowers who could not make the higher payments once the initial grace period ended would try to refinance their mortgages. Refinancing became more difficult, once house prices began to decline in many parts of the USA. Borrowers who found themselves unable to escape higher monthly payments by refinancing began to default. During 2007, lenders had begun foreclosure proceedings on nearly 1.3 million properties, a 79% increase over 2006.[24] This increased to 2.3 million in 2008, an 81% increase vs. 2007.[25] As of August 2008, 9.2% of all mortgages outstanding were either delinquent or in foreclosure.[26]

The Economist described the issue this way: "No part of the financial crisis has received so much attention, with so little to show for it, as the tidal wave of home foreclosures sweeping over America. Government programmes have been ineffectual, and private efforts not much better." Up to 9 million homes may enter foreclosure over the 2009-2011 period, versus one million in a typical year.[27]At roughly U.S. $50,000 per foreclosure according to a 2006 study by the Chicago Federal Reserve Bank, 9 million foreclosures represents $450 billion in losses.[28]

Sub-prime lending

In addition to easy credit conditions, there is evidence that both government and competitive pressures contributed to an increase in the amount of subprime lending during the years preceding the crisis. Major U.S. investment banks and government sponsored enterprises like Fannie Mae played an important role in the expansion of higher-risk lending.[29][30]

The term subprime refers to the credit quality of particular borrowers, who have weakened credit histories and a greater risk of loan default than prime borrowers.[31] The value of U.S. subprime mortgages was estimated at $1.3 trillion as of March 2007,[32] with over 7.5 million first-lien subprime mortgages outstanding.[33]

Subprime mortgages remained below 10% of all mortgage originations until 2004, when they spiked to nearly 20% and remained there through the 2005-2006 peak of the United States housing bubble.[34] A proximate event to this increase was the April 2004 decision by the SEC to relax the net capital rule, which encouraged the largest five investment banks to dramatically increase their financial leverage and aggressively expand their issuance of mortgage-backed securities. This applied additional competitive pressure to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which further expanded their riskier lending.[35] Subprime mortgage payment delinquency rates remained in the 10-15% range from 1998 to 2006[36], then began to increase rapidly, rising to 25% by early 2008.[37][38]

Government pressure to expand home ownership

Some, like American Enterprise Institute fellow Peter J. Wallison[39], believe the roots of the crisis can be traced directly to sub-prime lending by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which are government sponsored entities. On 30 September 1999, The New York Times reported that the Clinton Administration pushed for sub-prime lending: "Fannie Mae, the nation's biggest underwriter of home mortgages, has been under increasing pressure from the Clinton Administration to expand mortgage loans among low and moderate income people...In moving, even tentatively, into this new area of lending, Fannie Mae is taking on significantly more risk, which may not pose any difficulties during flush economic times. But the government-subsidized corporation may run into trouble in an economic downturn, prompting a government rescue similar to that of the savings and loan industry in the 1980s."[40]

In 1995, the administration also tinkered with President Jimmy Carter's Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 by regulating and strengthening the anti-redlining procedures. The result was a push by the administration for greater investment, by financial institutions, into riskier loans. A 2000 United States Department of the Treasury study of lending trends for 305 cities from 1993 to 1998 showed that $467 billion of mortgage credit poured out of CRA-covered lenders into low and mid level income borrowers and neighborhoods.[41]

Mortgage underwriting

In addition to considering higher-risk borrowers, lenders have offered increasingly risky loan options and borrowing incentives. Mortgage underwriting standards declined precipitously during the boom period. The use of automated loan approvals allowed loans to be made without appropriate review and documentation.[42] In 2007, 40% of all subprime loans resulted from automated underwriting.[43][44] The chairman of the Mortgage Bankers Association claimed that mortgage brokers, while profiting from the home loan boom, did not do enough to examine whether borrowers could repay.[45] Mortgage fraud by lenders and borrowers increased enormously. [46]

A study by the Federal Reserve found that the average difference between subprime and prime mortgage interest rates (the "subprime markup") declined significantly between 2001 and 2007. The combination of declining risk premia and credit standards is common to boom and bust credit cycles.[47]

Mortgage fraud

In 2004, the Federal Bureau of Investigation warned of an "epidemic" in mortgage fraud, an important credit risk of nonprime mortgage lending, which, they said, could lead to "a problem that could have as much impact as the S&L crisis".[48] [49][50][51]

Sufficiency of down payments

A down payment refers to the cash paid to the lender for the home and represents the initial homeowners equity or financial interest in the home. In 2005, the median down payment for first-time home buyers was 2%, with 43% of those buyers making no down payment whatsoever.[52] By comparison, China has down payment requirements that exceed 20%, with higher amounts for non-primary residences.[53]

Economist Nouriel Roubini wrote in Forbes in July 2009: "Home prices have already fallen from their peak by about 30%. Based on my analysis, they are going to fall by at least 40% from their peak, and more likely 45%, before they bottom out. They are still falling at an annualized rate of over 18%. That fall of at least 40%-45% percent of home prices from their peak is going to imply that about half of all households that have a mortgage--about 25 million of the 51 million that have mortgages--are going to be underwater with negative equity and will have a significant incentive to walk away from their homes."[54]

Economist Stan Leibowitz argued in the Wall Street Journal that the extent of equity in the home was the key factor in foreclosure, rather than the type of loan, credit worthiness of the borrower, or ability to pay. Although only 12% of homes had negative equity (meaning the property was worth less than the mortgage obligation), they comprised 47% of foreclosures during the second half of 2008. Homeowners with negative equity have less financial incentive to stay in the home.[55]

Predatory lending

Predatory lending refers to the practice of unscrupulous lenders, to enter into "unsafe" or "unsound" secured loans for inappropriate purposes.[56] A classic bait-and-switch method was used by Countrywide, advertising low interest rates for home refinancing. Such loans were written into mind-numbingly detailed contracts, and swapped for more expensive loan products on the day of closing. Whereas the advertisement might state that 1% or 1.5% interest would be charged, the consumer would be put into an adjustable rate mortgage (ARM) in which the interest charged would be greater than the amount of interest paid. This created negative amortization, which the credit consumer might not notice until long after the loan transaction had been consummated.

Countrywide, sued by California Attorney General Jerry Brown for "Unfair Business Practices" and "False Advertising" was making high cost mortgages "to homeowners with weak credit, adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs) that allowed homeowners to make interest-only payments." [57]. When housing prices decreased, homeowners in ARMs then had little incentive to pay their monthly payments, since their home equity had disappeared. This caused Countrywide's financial condition to deteriorate, ultimately resulting in a decision by the Office of Thrift Supervision to seize the lender.

Countrywide, according to Republican Lawmakers, had involved itself in making low-cost loans to politicians, for purposes of gaining political favors. [58].

Former employees from Ameriquest, which was United States's leading wholesale lender,[59] described a system in which they were pushed to falsify mortgage documents and then sell the mortgages to Wall Street banks eager to make fast profits.[59] There is growing evidence that such mortgage frauds may be a cause of the crisis.[59]

Risk-taking behavior

Consumer and household borrowing

U.S. households and financial institutions became increasingly indebted or overleveraged during the years preceding the crisis. This increased their vulnerability to the collapse of the housing bubble and worsened the ensuing economic downturn.

- USA household debt as a percentage of annual disposable personal income was 127% at the end of 2007, versus 77% in 1990.[60]

- U.S. home mortgage debt relative to gross domestic product (GDP) increased from an average of 46% during the 1990s to 73% during 2008, reaching $10.5 trillion.[61]

- In 1981, U.S. private debt was 123% of GDP; by the third quarter of 2008, it was 290%.[62]

Home equity extraction

This refers to homeowners borrowing and spending against the value of their homes, typically via a home equity loan or when selling the home. Free cash used by consumers from home equity extraction doubled from $627 billion in 2001 to $1,428 billion in 2005 as the housing bubble built, a total of nearly $5 trillion dollars over the period, contributing to economic growth world-wide.[63][64][65] U.S. home mortgage debt relative to GDP increased from an average of 46% during the 1990's to 73% during 2008, reaching $10.5 trillion.[66]

Housing speculation

Speculative borrowing in residential real estate has been cited as a contributing factor to the subprime mortgage crisis.[67] During 2006, 22% of homes purchased (1.65 million units) were for investment purposes, with an additional 14% (1.07 million units) purchased as vacation homes. During 2005, these figures were 28% and 12%, respectively. In other words, a record level of nearly 40% of homes purchases were not intended as primary residences. David Lereah, NAR's chief economist at the time, stated that the 2006 decline in investment buying was expected: "Speculators left the market in 2006, which caused investment sales to fall much faster than the primary market."[68]

Housing prices nearly doubled between 2000 and 2006, a vastly different trend from the historical appreciation at roughly the rate of inflation. While homes had not traditionally been treated as investments subject to speculation, this behavior changed during the housing boom. Media widely reported condominiums being purchased while under construction, then being "flipped" (sold) for a profit without the seller ever having lived in them.[69] Some mortgage companies identified risks inherent in this activity as early as 2005, after identifying investors assuming highly leveraged positions in multiple properties.[70]

Nicole Gelinas of the Manhattan Institute described the negative consequences of not adjusting tax and mortgage policies to the shifting treatment of a home from conservative inflation hedge to speculative investment.[71] Economist Robert Shiller argued that speculative bubbles are fueled by "contagious optimism, seemingly impervious to facts, that often takes hold when prices are rising. Bubbles are primarily social phenomena; until we understand and address the psychology that fuels them, they're going to keep forming."[72]

Pro-cyclical human nature

Keynesian economist Hyman Minsky described how speculative borrowing contributed to rising debt and an eventual collapse of asset values.[73] Economist Paul McCulley described how Minsky's hypothesis translates to the current crisis, using Minsky's words: "...from time to time, capitalist economies exhibit inflations and debt deflations which seem to have the potential to spin out of control. In such processes, the economic system's reactions to a movement of the economy amplify the movement--inflation feeds upon inflation and debt-deflation feeds upon debt deflation." In other words, people are momentum investors by nature, not value investors. People naturally take actions that expand the apex and nadir of cycles. One implication for policymakers and regulators is the implementation of counter-cyclical policies, such as contingent capital requirements for banks that increase during boom periods and are reduced during busts.[74]

Corporate risk-taking and leverage

From 2004-07, the top five U.S. investment banks each significantly increased their financial leverage (see diagram), which increased their vulnerability to a financial shock. These five institutions reported over $4.1 trillion in debt for fiscal year 2007, about 30% of USA nominal GDP for 2007. Lehman Brothers was liquidated, Bear Stearns and Merrill Lynch were sold at fire-sale prices, and Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley became commercial banks, subjecting themselves to more stringent regulation. With the exception of Lehman, these companies required or received government support.[75]

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, two U.S. Government sponsored enterprises, owned or guaranteed nearly $5 trillion in mortgage obligations at the time they were placed into conservatorship by the U.S. government in September 2008.[76][77]

These seven entities were highly leveraged and had $9 trillion in debt or guarantee obligations, an enormous concentration of risk, yet were not subject to the same regulation as depository banks.

In a May 2008 speech, Ben Bernanke quoted Walter Bagehot: "A good banker will have accumulated in ordinary times the reserve he is to make use of in extraordinary times."[78]However, this advice was not heeded by these investment banks, which used the boom times to increase their leverage ratio, just the opposite of what Bagehot counseled.

Financial market factors

Financial product innovation

The term financial innovation refers to the ongoing development of financial products designed to achieve particular client objectives, such as offsetting a particular risk exposure (such as the default of a borrower) or to assist with obtaining financing. Examples pertinent to this crisis included: the adjustable-rate mortgage; the bundling of subprime mortgages into mortgage-backed securities (MBS) or collateralized debt obligations (CDO) for sale to investors, a type of securitization; and a form of credit insurance called credit default swaps(CDS). The usage of these products expanded dramatically in the years leading up to the crisis. These products vary in complexity and the ease with which they can be valued on the books of financial institutions.

The CDO in particular enabled financial institutions to obtain investor funds to finance subprime and other lending, extending or increasing the housing bubble and generating large fees. A CDO essentially places cash payments from multiple mortgages or other debt obligations into a single pool, from which the cash is allocated to specific securities in a priority sequence. Those securities obtaining cash first received investment-grade ratings from rating agencies. Lower priority securities received cash thereafter, with lower credit ratings but theoretically a higher rate of return on the amount invested.[79][80]

For a variety of reasons, market participants did not accurately measure the risk inherent with this innovation or understand its impact on the overall stability of the financial system.[81] For example, the pricing model for CDOs clearly did not reflect the level of risk they introduced into the system. The average recovery rate for "high quality" CDOs has been approximately 32 cents on the dollar, while the recovery rate for mezzanine CDO's has been approximately five cents for every dollar. These massive, practically unthinkable, losses have dramatically impacted the balance sheets of banks across the globe, leaving them with very little capital to continue operations.[82]

Others have pointed out that there were not enough of these loans made to cause a crisis of this magnitude. In an article in Portfolio Magazine, Michael Lewis spoke with one trader who noted that "There weren’t enough Americans with [bad] credit taking out [bad loans] to satisfy investors’ appetite for the end product." Essentially, investment banks and hedge funds used financial innovation to synthesize more loans using derivatives. "They were creating [loans] out of whole cloth. One hundred times over! That’s why the losses are so much greater than the loans."[83]

Another example relates to AIG, which insured obligations of various financial institutions through the usage of credit default swaps. The basic CDS transaction involved AIG receiving a premium in exchange for a promise to pay money to party A in the event party B defaulted. However, AIG did not have the financial strength to support its many CDS commitments as the crisis progressed and was taken over by the government in September 2008. U.S. taxpayers provided over $180 billion in government support to AIG during 2008 and early 2009, through which the money flowed to various counterparties to CDS transactions, including many large global financial institutions.[84][85]

Inaccurate credit ratings

Credit rating agencies are now under scrutiny for having given investment-grade ratings to MBSs based on risky subprime mortgage loans. These high ratings enabled these MBS to be sold to investors, thereby financing the housing boom. These ratings were believed justified because of risk reducing practices, such as credit default insurance and equity investors willing to bear the first losses. However, there are also indications that some involved in rating subprime-related securities knew at the time that the rating process was faulty.[86]

Critics allege that the rating agencies suffered from conflicts of interest, as they were paid by investment banks and other firms that organize and sell structured securities to investors.[87] On 11 June 2008, the SEC proposed rules designed to mitigate perceived conflicts of interest between rating agencies and issuers of structured securities.[88] On 3 December 2008, the SEC approved measures to strengthen oversight of credit rating agencies, following a ten-month investigation that found "significant weaknesses in ratings practices," including conflicts of interest.[89]

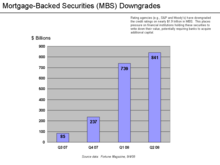

Between Q3 2007 and Q2 2008, rating agencies lowered the credit ratings on $1.9 trillion in mortgage backed securities. Financial institutions felt they had to lower the value of their MBS and acquire additional capital so as to maintain capital ratios. If this involved the sale of new shares of stock, the value of the existing shares was reduced. Thus ratings downgrades lowered the stock prices of many financial firms.[90]

Financial modeling

The limitations of a widely-used financial model also were not properly understood.[91][92] This formula assumed that the price of CDS was correlated with and could predict the correct price of mortgage backed securities. Because it was highly tractable, it rapidly came to be used by a huge percentage of CDO and CDS investors, issuers, and rating agencies.[92] According to one wired.com article[92]: "Then the model fell apart. Cracks started appearing early on, when financial markets began behaving in ways that users of Li's formula hadn't expected. The cracks became full-fledged canyons in 2008—when ruptures in the financial system's foundation swallowed up trillions of dollars and put the survival of the global banking system in serious peril... Li's Gaussian copula formula will go down in history as instrumental in causing the unfathomable losses that brought the world financial system to its knees."

As financial assets became more and more complex, and harder and harder to value, investors were reassured by the fact that both the international bond rating agencies and bank regulators, who came to rely on them, accepted as valid some complex mathematical models which theoretically showed the risks were much smaller than they actually proved to be in practice [93]. George Soros commented that "The super-boom got out of hand when the new products became so complicated that the authorities could no longer calculate the risks and started relying on the risk management methods of the banks themselves. Similarly, the rating agencies relied on the information provided by the originators of synthetic products. It was a shocking abdication of responsibility." [94]

Regulatory avoidance

Certain financial innovation may also have the effect of circumventing regulations, such as off-balance sheet financing that affects the leverage or capital cushion reported by major banks. For example, Martin Wolf wrote in June 2009: "...an enormous part of what banks did in the early part of this decade – the off-balance-sheet vehicles, the derivatives and the 'shadow banking system' itself – was to find a way round regulation."[95]

Boom and collapse of the shadow banking system

In a June 2008 speech, U.S. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, then President and CEO of the NY Federal Reserve Bank, placed significant blame for the freezing of credit markets on a "run" on the entities in the "parallel" banking system, also called the shadow banking system. These entities became critical to the credit markets underpinning the financial system, but were not subject to the same regulatory controls. Further, these entities were vulnerable because they borrowed short-term in liquid markets to purchase long-term, illiquid and risky assets. This meant that disruptions in credit markets would make them subject to rapid deleveraging, selling their long-term assets at depressed prices. He described the significance of these entities: "In early 2007, asset-backed commercial paper conduits, in structured investment vehicles, in auction-rate preferred securities, tender option bonds and variable rate demand notes, had a combined asset size of roughly $2.2 trillion. Assets financed overnight in triparty repo grew to $2.5 trillion. Assets held in hedge funds grew to roughly $1.8 trillion. The combined balance sheets of the then five major investment banks totaled $4 trillion. In comparison, the total assets of the top five bank holding companies in the United States at that point were just over $6 trillion, and total assets of the entire banking system were about $10 trillion." He stated that the "combined effect of these factors was a financial system vulnerable to self-reinforcing asset price and credit cycles."[96]

Nobel laureate Paul Krugman described the run on the shadow banking system as the "core of what happened" to cause the crisis. "As the shadow banking system expanded to rival or even surpass conventional banking in importance, politicians and government officials should have realized that they were re-creating the kind of financial vulnerability that made the Great Depression possible—and they should have responded by extending regulations and the financial safety net to cover these new institutions. Influential figures should have proclaimed a simple rule: anything that does what a bank does, anything that has to be rescued in crises the way banks are, should be regulated like a bank." He referred to this lack of controls as "malign neglect."[97]

Mortgage compensation model, executive pay and bonuses

During the boom period, enormous fees were paid to those throughout the mortgage supply chain, from the mortgage broker selling the loans, to small banks that funded the brokers, to the giant investment banks behind them. Those originating loans were paid fees for selling them, regardless of how the loans performed. Default or credit risk was passed from mortgage originators to investors using various types of financial innovation.[98] This became known as the "originate to distribute" model, as opposed to the traditional model where the bank originating the mortgage retained the credit risk. In effect, the mortgage originators had no "skin in the game," giving rise to moral hazard, in which behavior and consequence were separated.

The New York State Comptroller's Office has said that in 2006, Wall Street executives took home bonuses totaling $23.9 billion. "Wall Street traders were thinking of the bonus at the end of the year, not the long-term health of their firm. The whole system—from mortgage brokers to Wall Street risk managers—seemed tilted toward taking short-term risks while ignoring long-term obligations. The most damning evidence is that most of the people at the top of the banks didn't really understand how those [investments] worked."[21][99]

Investment banker incentive compensation was focused on fees generated from assembling financial products, rather than the performance of those products and profits generated over time. Their bonuses were heavily skewed towards cash rather than stock and not subject to "claw-back" (recovery of the bonus from the employee by the firm) in the event the MBS or CDO created did not perform. In addition, the increased risk (in the form of financial leverage) taken by the major investment banks was not adequately factored into the compensation of senior executives.[100]

Bank CEO Jamie Dimon argued: "Rewards have to track real, sustained, risk-adjusted performance. Golden parachutes, special contracts, and unreasonable perks must disappear. There must be a relentless focus on risk management that starts at the top of the organization and permeates down to the entire firm. This should be business-as-usual, but at too many places, it wasn't."[101]

Regulation and Deregulation

Critics have argued that the regulatory framework did not keep pace with financial innovation, such as the increasing importance of the shadow banking system, derivatives and off-balance sheet financing. In other cases, laws were changed or enforcement weakened in parts of the financial system. Key examples include:

- In 1999, the U.S. Congress passed the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, which repealed part of the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933. This repeal has been criticized for reducing the separation between commercial banks (which traditionally had a conservative culture) and investment banks (which had a more risk-taking culture).[102][103]

- In 2004, the Securities and Exchange Commission relaxed the net capital rule, which enabled investment banks to substantially increase the level of debt they were taking on, fueling the growth in mortgage-backed securities supporting subprime mortgages. The SEC has conceded that self-regulation of investment banks contributed to the crisis.[104][105]

- Financial institutions in the shadow banking system are not subject to the same regulation as depository banks, allowing them to assume additional debt obligations relative to their financial cushion or capital base.[106] This was the case despite the Long-Term Capital Management debacle in 1998, where a highly-leveraged shadow institution failed with systemic implications.

- Regulators and accounting standard-setters allowed depository banks such as Citigroup to move significant amounts of assets and liabilities off-balance sheet into complex legal entities called structured investment vehicles, masking the weakness of the capital base of the firm or degree of leverage or risk taken. One news agency estimated that the top four U.S. banks will have to return between $500 billion and $1 trillion to their balance sheets during 2009.[107] This increased uncertainty during the crisis regarding the financial position of the major banks.[108] Off-balance sheet entities were also used by Enron as part of the scandal that brought down that company in 2001.[109]

- The U.S. Congress allowed the self-regulation of the derivatives market when it passed the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000. Derivatives such as credit default swaps (CDS) can be used to hedge or speculate against particular credit risks. The volume of CDS outstanding increased 100-fold from 1998 to 2008, with estimates of the debt covered by CDS contracts, as of November 2008, ranging from US$33 to $47 trillion. Total over-the-counter (OTC) derivative notional value rose to $683 trillion by June 2008.[110] Warren Buffett famously referred to derivatives as "financial weapons of mass destruction" in early 2003.[111][112]

Other factors

Commodity price volatility

A commodity price bubble was created following the collapse in the housing bubble. The price of oil nearly tripled from $50 to $140 from early 2007 to 2008, before plunging as the financial crisis began to take hold in late 2008.[113] Experts debate the causes, which include the flow of money from housing and other investments into commodities to speculation and monetary policy.[114] An increase in oil prices tends to divert a larger share of consumer spending into gasoline, which creates downward pressure on economic growth in oil importing countries, as wealth flows to oil-producing states.[115]

Inaccurate economic forecasting

A cover story in BusinessWeek Magazine claims that economists mostly failed to predict the worst international economic crisis since the Great Depression of 1930s. [116]. The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania online business journal examines why economists failed to predict a major global financial crisis [4]. An article in the New York Times informs that economist Nouriel Roubini warned of such crisis as early as September 2006, and the article goes on to state that the profession of economics is bad at predicting recessions. [117] According to The Guardian, Roubini was ridiculed for predicting a collapse of the housing market and worldwide recession, while The New York Times labelled him "Dr. Doom". [118] However, there are examples of other experts who gave indications of a financial crisis.[119][120][121]

Monetary expansion and uncertainty

An empirical study by John B. Taylor concluded that the crisis was: (1) caused by excess monetary expansion; (2) prolonged by an inability to evaluate counter-party risk due to opaque financial statements; and (3) worsened by the unpredictable nature of government's response to the crisis.[122][123]

Systemic crisis

Another analysis, different from the mainstream explanation, is that the financial crisis is merely a symptom of another, deeper crisis, which is a systemic crisis of capitalism itself. According to Samir Amin, an Egyptian economist, the constant decrease in GDP growth rates in Western countries since the early 1970s created a growing surplus of capital which did not have sufficient profitable investment outlets in the real economy. The alternative was to place this surplus into the financial market, which became more profitable than productive capital investment, especially with subsequent deregulation.[124] According to Samir Amin, this phenomenon has lead to recurrent financial bubbles (such as the internet bubble) and is the deep cause of the financial crisis of 2007-2009.[125]

John Bellamy Foster, a political economy analyst and editor of the Monthly Review, believes that the decrease in GDP growth rates since the early 1970s is due to increasing market saturation.[126]

John C. Bogle wrote during 2005 that a series of unresolved challenges face capitalism that have contributed to past financial crises and have not been sufficiently addressed: "Corporate America went astray largely because the power of managers went virtually unchecked by our gatekeepers for far too long...They failed to 'keep an eye on these geniuses' to whom they had entrusted the responsibility of the management of America's great corporations." He cites particular issues, including:[127][128]

- "Manager's capitalism" which he argues has replaced "owner's capitalism," meaning management runs the firm for its benefit rather than for the shareholders, a variation on the principal-agent problem;

- Burgeoning executive compensation;

- Managed earnings, mainly a focus on share price rather than the creation of genuine value; and

- The failure of gatekeepers, including auditors, boards of directors, Wall Street analysts, and career politicians.

Interaction of the housing and financial markets

One of the unique features of this crisis relative to previous crises is the interaction of various markets involved. As borrowers stop paying their mortgages, foreclosures and the supply of homes for sale increases. This places downward pressure on housing prices, which further lowers homeowners' equity. The decline in mortgage payments also reduces the value of mortgage-backed securities, which erodes the net worth and financial health of banks. This reduces the amount of lending that banks can support, which slows down business investment. When consumers do not spend, business earnings are impacted, which increases unemployment. This vicious cycle or self-reinforcing loop is at the heart of the crisis.[129]

Thomas Friedman summarized some of this interaction in November 2008:[130]

When these reckless mortgages eventually blew up, it led to a credit crisis. Banks stopped lending. That soon morphed into an equity crisis, as worried investors liquidated stock portfolios. The equity crisis made people feel poor and metastasized into a consumption crisis, which is why purchases of cars, appliances, electronics, homes and clothing have just fallen off a cliff. This, in turn, has sparked more company defaults, exacerbated the credit crisis and metastasized into an unemployment crisis, as companies rush to shed workers.

See also

References

- ^ Bernanke-Four Questions

- ^ "Episode 06292007". Bill Moyers Journal. 2007-06-29. PBS.

{{cite episode}}: External link in|transcripturl=|transcripturl=ignored (|transcript-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Justin Lahart (2007-12-24). "Egg Cracks Differ In Housing, Finance Shells". WSJ.com. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ Bernanke-Four Questions About the Financial Crisis

- ^ Krugman-Revenge of the Glut

- ^ IMF Loss Estimates

- ^ Geithner-Speech Reducing Systemic Risk in a Dynamic Financial System

- ^ Greenspan-We Need a Better Cushion Against Risk

- ^ "Federal Reserve Board: Monetary Policy and Open Market Operations". Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ^ "The Wall Street Journal Online - Featured Article". 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ^ Fed Historical Data-Fed Funds Rate

- ^ National Review - Mastrobattista

- ^ CNN-The Bubble Question

- ^ Business Week-Is a Housing Bubble About to Burst?

- ^ "Bernanke-The Global Saving Glut and U.S. Current Account Deficit". Federalreserve.gov. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ^ "Chairman Ben S. Bernanke, At the Bundesbank Lecture, Berlin, Germany September 11, 2007: Global Imbalances: Recent Developments and Prospects". Federalreserve.gov. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|title=at position 69 (help) - ^ "Economist-When a Flow Becomes a Flood". Economist.com. 2009-01-22. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ^ Roger C. Altman. "Altman-Foreign Affairs-The Great Crash of 2008". Foreignaffairs.org. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ^ NPR-The Giant Pool of Money

- ^ "CSI: credit crunch". 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

{{cite news}}: Text "Economist.com" ignored (help) - ^ a b Ben Steverman and David Bogoslaw (October 18, 2008, 12:01AM EST). "The Financial Crisis Blame Game - BusinessWeek". Businessweek.com. Retrieved 2008-10-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ [1]

- ^ "Economist-A Helping Hand to Homeowners". Economist.com. 2008-10-23. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ^ "U.S. FORECLOSURE ACTIVITY INCREASES 75 PERCENT IN 2007". RealtyTrac. 2008-01-29. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- ^ "RealtyTrac Press Release 2008FY". Realtytrac.com. 2009-01-15. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ^ "MBA Survey".

- ^ Economist - Can't Pay or Won't Pay?

- ^ NYT-Times Topics-Foreclosures

- ^ NY Times-The Reckoning-Agency 04 Rule Lets Banks Pile on Debt

- ^ NYT-The Reckoning-Pressured to Take More Risk, Fannie Reached Tipping Point

- ^ FDIC-Guidance for Subprime Lending

- ^ "How severe is subprime mess?". msnbc.com. Associated Press. 2007-03-13. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ Ben S. Bernanke (2007-05-17). The Subprime Mortgage Market (Speech). Chicago, Illinois. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ Harvard Report-State of the Nation's Housing 2008 Report

- ^ NY Times - The Reckoning - Agency 04 Rule Lets Banks Pile on Debt

- ^ Chicago Federal Reserve Letter August 2007

- ^ Bernanke-Mortgage Delinquencies and Foreclosures May 2008

- ^ Mortgage Bankers Association - National Delinquency Survey

- ^ What Got Us Here?, December 2008.

- ^ Holmes, Steven A. (September 30, 1999), "Fannie Mae Eases Credit To Aid Mortgage Lending", The New York Times, pp. section C page 2, retrieved 2009-03-08

- ^ The Community Reinvestment Act After Financial Modernization, April 2000.

- ^ "Bank Systems & Technology". 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ^ Lynnley Browning (2007-03-27). "The Subprime Loan Machine". nytimes.com. New York City: Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ "REALTOR Magazine-Daily News-Are Computers to Blame for Bad Lending?". 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ^ "Brokers, bankers play subprime blame game - Real estate - MSNBC.com". 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ^ Tyler Cowen (Published: January 13, 2008). "So We Thought. But Then Again . . . - New York Times". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^

Demyanyk, Yuliya (2008-08-19). "Understanding the Subprime Mortgage Crisis". Working Paper Series. Social Science Electronic Publishing. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.cnn.com/2004/LAW/09/17/mortgage.fraud/ FBI warns of mortgage fraud 'epidemic'

- ^ http://www.fbi.gov/pressrel/pressrel05/quickflip121405.htm FBI Press Release on "Operation Quickflip"

- ^ http://articles.latimes.com/2008/aug/25/business/fi-mortgagefraud25 FBI saw threat of mortgage crisis

- ^ http://www.huffingtonpost.com/william-k-black/the-two-documents-everyon_b_169813.html The Two Documents Everyone Should Read to Better Understand the Crisis

- ^ Knox, Noelle (2006-01-17). "43% of first-time home buyers put no money down". USA Today. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ^ "China Down Payment Requirements". Sgpropertypress.wordpress.com. 2007-09-19. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ^ Roubini-10 Risks to Global Growth

- ^ WSJ Leibowitz - New Evidence On Foreclosure Crisis

- ^ http://banking.senate.gov/docs/reports/predlend/occ.htm

- ^ http://thinkdebtrelief.com/debt-relief-blog/money-news/bofa-modifies-64000-home-loans-as-part-of-predatory-lending-settlement/

- ^ http://republicans.oversight.house.gov/media/pdfs/20090319FriendsofAngelo.pdf

- ^ a b c Road to Ruin: Mortgage Fraud Scandal Brewing May 13, 2009 by American News Project hosted by The Real News

- ^ "The End of the Affair". Economist. 2008-10-30. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ^ Fortune-The $4 trillion housing headache

- ^ FT-Wolf Japan's Lessons

- ^ Greenspan Kennedy Report - Table 2

- ^ Equity extraction - Charts

- ^ Reuters-Spending Boosted by Home Equity Loans

- ^ Fortune-The $4 trillion housing headache

- ^ Louis uchitelle (October 26, 1996). "H. P. Minsky, 77, Economist Who Decoded Lending Trends". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ "Speculation statistics".

- ^ "Speculative flipping".

- ^ "Speculation Risks".

- ^ Gelinas-Sheltering Speculation. City-journal.com

- ^ Crook, Clive. "Shiller-Infectious Exuberance-The Atlantic". Theatlantic.com. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ^ "Does the Current Financial Crisis Vindicate the Economics of Hyman Minsky? - Frank Shostak - Mises Institute". Mises.org. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- ^ McCulley-PIMCO-The Shadow Banking System and Hyman Minsky's Economic Journey

- ^ "Agency's '04 Rule Let Banks Pile Up New Debt, and Risk".

- ^ "AEI-The Last Trillion Dollar Commitment". Aei.org. Retrieved 2009-02-27. American Enterprise Institute is a conservative organization with a right- of-center political agenda .

- ^ "Bloomberg-U.S. Considers Bringing Fannie & Freddie Onto Budget". Bloomberg.com. 2008-09-11. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ^ Ben Bernanke

- ^ CDO Explained

- ^ Portfolio-CDO Explained

- ^ "Declaration of G20". Whitehouse.gov. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ^ http://tpmcafe.talkingpointsmemo.com/talk/blogs/paulw/2009/03/the-power-of-belief.php

- ^ Portfolio-Michael Lewis-"The End"-December 2008

- ^ "Bloomberg-Credit Swap Disclosure Obscures True Financial Risk". Bloomberg.com. 2008-11-06. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ^ Business Week-Who's Who on AIG List of Counterparties

- ^ US House of Representatives Committee on Government Oversight and Reform (22 October 2008). "Committee Holds Hearing on the Credit Rating Agencies and the Financial Crisis". Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- ^ "Buttonwood | Credit and blame | Economist.com". Economist.com. 6 September 2007. Retrieved 26 October 2008.

- ^ "SEC Proposes Comprehensive Reforms to Bring Increased Transparency to Credit Rating Process". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. 2008. Retrieved July 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "SEC - Rating Agency Rules". Sec.gov. 2008-12-03. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ^ "The woman who called Wall Street's meltdown". Fortune. 6 August 2008.

- ^ http://moneyfeatures.blogs.money.cnn.com/2009/02/27/the-financial-crisis-why-did-it-happen/

- ^ a b c Salmon, Felix (2009-02-23), "Recipe for Disaster: The Formula That Killed Wall Street", Wired Magazine, no. 17.03, retrieved 2009-03-08

- ^ Floyd Norris (2008). News Analysis: Another Crisis, Another Guarantee, The New York Times, November 24, 2008

- ^ Soros, George (January 22, 2008), "The worst market crisis in 60 years", Financial Times, London, UK, retrieved 2009-03-08

- ^ FT Martin Wolf - Reform of Regulation and Incentives

- ^ Geithner-Speech Reducing Systemic Risk in a Dynamic Financial System

- ^ Krugman, Paul (2009). The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008. W.W. Norton Company Limited. ISBN 978-0-393-07101-6.

- ^ NPR-The Giant Pool of Money

- ^ NYT-Nocera-First, Let's Fix the Bonuses

- ^ NYT-Reckoning-Profits Illusory, Bonuses Real

- ^ WSJ - JPM CEO Jamie Dimon

- ^ Stiglitz-Capitalist Fools

- ^ Ekelund, Robert (2008-09-04). "More Awful Truths About Republicans". Ludwig von Mises Institute. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "SEC Concedes Oversight Flaws".

- ^ "The Reckoning".

- ^ Krugman, Paul (2009). The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008. W.W. Norton Company Limited. ISBN 978-0-393-07101-6.

- ^ Bloomberg-Bank Hidden Junk Menaces $1 Trillion Purge

- ^ Bloomberg-Citigroup SIV Accounting Tough to Defend

- ^ Healy, Paul M. & Palepu, Krishna G.: "The Fall of Enron" (Journal of Economics Perspectives, Volume 17, Number 2. (Spring 2003), p.13

- ^ Forbes-Geithner's Plan for Derivatives

- ^ The Economist-Derivatives-A Nuclear Winter?

- ^ BBC-Buffet Warns on Investment Time Bomb

- ^ Light Crude Oil Chart

- ^ Soros - Rocketing Oil Price is a Bubble

- ^ Mises Institute-The Oil Price Bubble

- ^ Businessweek Magazine

- ^ [2]"Dr. Doom", By Stephen Mihm, August 15, 2008, New York Times Magazine

- ^ [3] Emma Brockes, "He Told Us So," The Guardian, January 24, 2009.

- ^ "Recession in America," The Economist, November 15, 2007.

- ^ Richard Berner, "Perfect Storm for the American Consumer," Morgan Stanley Global Economic Forum, November 12, 2007.

- ^ Kabir Chibber, "Goldman Sees Subprime Cutting $2 Trillion in Lending," Bloomberg.com, November 16, 2007.

- ^ The Financial Crisis and the Policy Responses: An Empirical Analysis of What Went Wrong

- ^ How Government Created the Financial Crisis

- ^ http://www.ismea.org/INESDEV/AMIN.eng.html

- ^ http://www.globalresearch.ca/index.php?context=va&aid=11099

- ^ http://monthlyreview.org/080401foster.php

- ^ Bogle, John (2005). The Battle for the Soul of Capitalism. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11971-8.

- ^ Battle for the Soul of Capitalism

- ^ Feldstein, Martin (2008-11-18). "NYT - How to Help People Whose Homes are Underwater". Online.wsj.com. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ^ Friedman-Gonna Need a Bigger Boat