United Macedonia: Difference between revisions

Macedonian (talk | contribs) →History of the concept: removed dead link |

Macedonian (talk | contribs) m →History of the concept: ref. |

||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

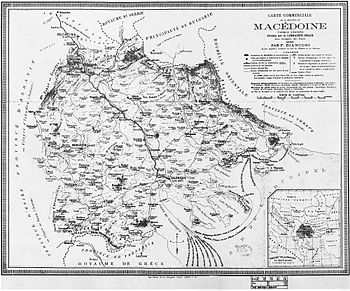

[[Image:85mapmacedonia.jpg|thumb|350px|Map of the whole geographical region of Macedonia as seen by [[F.Bianconi]], 1885.]] |

[[Image:85mapmacedonia.jpg|thumb|350px|Map of the whole geographical region of Macedonia as seen by [[F.Bianconi]], 1885.]] |

||

The United Macedonia concept is still found among official sources in the Republic,<ref name="Times"/><ref name="Bulgaria">{{cite web | last = Lenkova | first = M. | coauthors = Dimitras, P., Papanikolatos, N., Law, C. (eds) | title =Greek Helsinki Monitor: Macedonians of Bulgaria | work = Minorities in Southeast Europe | publisher =Greek Helsinki Monitor, Center for Documentation and Information on Minorities in Europe — Southeast Europe | year = 1999 | url = http://www.greekhelsinki.gr/pdf/cedime-se-bulgaria-macedonians.PDF | format = pdf | accessdate= July 24, 2006}}</ref><ref name="Currency">{{cite news| first=Marlise |last=Simons |title=As Republic Flexes, Greeks Tense Up |date=February 3, 1992 |publisher=New York Times | url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E0CE0DD103CF930A35751C0A964958260}}</ref><ref name=Danforth>{{cite book| title=How can a woman give birth to one Greek and one Macedonian? | url= http://www.gate.net/~mango/How_can_a_woman_give_birth.htm | work=The construction of national identity among immigrants to Australia from Northern Greece | first=Loring M. | last= Danforth |accessdate=2006-12-26 }}</ref> and taught in schools through school textbooks and through other governmental publications<ref>''Facts About the Republic of Macedonia'' - annual booklets since 1992, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia Secretariat of Information, Second edition, 1997, ISBN 9989-42-044-0. p.14. 2 August 1944.</ref><ref>{{cite web| url= http://www.macedonianembassy.org.uk/history.html | title= Official site of the Embassy of the Republic of Macedonia in London | work= An outline of Macedonian history from Ancient times to 1991 | accessdate=2006-12-26 }}</ref> |

The United Macedonia concept is still found among official sources in the Republic,<ref name="Times"/><ref name="Bulgaria">{{cite web | last = Lenkova | first = M. | coauthors = Dimitras, P., Papanikolatos, N., Law, C. (eds) | title =Greek Helsinki Monitor: Macedonians of Bulgaria | work = Minorities in Southeast Europe | publisher =Greek Helsinki Monitor, Center for Documentation and Information on Minorities in Europe — Southeast Europe | year = 1999 | url = http://www.greekhelsinki.gr/pdf/cedime-se-bulgaria-macedonians.PDF | format = pdf | accessdate= July 24, 2006}}</ref><ref name="Currency">{{cite news| first=Marlise |last=Simons |title=As Republic Flexes, Greeks Tense Up |date=February 3, 1992 |publisher=New York Times | url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E0CE0DD103CF930A35751C0A964958260}}</ref><ref name=Danforth>{{cite book| title=How can a woman give birth to one Greek and one Macedonian? | url= http://www.gate.net/~mango/How_can_a_woman_give_birth.htm | work=The construction of national identity among immigrants to Australia from Northern Greece | first=Loring M. | last= Danforth |accessdate=2006-12-26 }}</ref> and taught in schools through school textbooks and through other governmental publications.<ref>''Facts About the Republic of Macedonia'' - annual booklets since 1992, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia Secretariat of Information, Second edition, 1997, ISBN 9989-42-044-0. p.14. 2 August 1944.</ref><ref>{{cite web| url= http://www.macedonianembassy.org.uk/history.html | title= Official site of the Embassy of the Republic of Macedonia in London | work= An outline of Macedonian history from Ancient times to 1991 | accessdate=2006-12-26 }}</ref><ref>''Macedonianism: |

||

FYROM'S expansionist designs against Greece after the Interim Accord (1995)'', Society for Macedonian Studies, Ephesus Publishing, 2007</ref> |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

Revision as of 06:57, 25 November 2010

This article needs editing to comply with Wikipedia's Manual of Style. (May 2010) |

United Macedonia ([Обединета Македонија, Obedineta Makedonija] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help)) is an irredentist concept among extreme ethnic Macedonian nationalists that aims to unify the transnational region of Macedonia in southeastern Europe, which they claim as their homeland, and which they assert was wrongfully divided under the Treaty of Bucharest in 1913, into a single state under Slavic domination with the Greek city of Thessaloniki (Solun in the Slavic languages) as its capital.[1]

History of the concept

The concept of a United Macedonia appeared initially in the late 19th century as variant called authonomous Macedonia in the documents of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization. The organization was founded in 1893 in Ottoman Thessaloniki by a "small band of anti-Ottoman Macedono-Bulgarian revolutionaries,[2] which considered Macedonia an indivisible territory and claimed all of its inhabitants "Macedonians", no matter their religion or ethnicity. The idea then was strictly political and did not imply a secession from Bulgarian ethnicity, but unity of all nationalities in the area.[3] The term United Macedonia has been in use since the early 1900s, notably in connection with the Balkan Socialist Federation.

Although the following perception is not limited to ethnic Macedonians, or extreme nationalists, the majority of ethnic Macedonians usually[citation needed] break down the region of Macedonia as follows, a categorisation which is considered offensive by itself by both Greeks and Bulgarians:

- Vardar Macedonia (Вардарска Македонија) - the Republic of Macedonia.

- Aegean Macedonia (Егејска Македонија) - the three Macedonian peripheries of northern Greece.

- Pirin Macedonia (Пиринска Македонија) - the unofficial name of Blagoevgrad Province in southwestern Bulgaria

- Mala Prespa and Golo Brdo (Мала Преспа и Голо Брдо) - an area in southeastern Albania (sometimes considered to be a part of Aegean Macedonia).

- Prohor Pchinski (Прохор Пчински) - in southern Serbia, (this subregion is considered to be a part of Vardar Macedonia).

- Gora (Гора) - in southern Kosovo (this subregion is also considered to be a part of Vardar Macedonia).

An essential aspect of this concept is the claim that the vast majority of the population in those territories are oppressed ethnic Macedonians and they describe those areas as the unliberated parts of Macedonia. In the cases of Bulgaria and Albania, it is said that they are undercounted in the censuses (In Albania, there are officially 5,000 ethnic Macedonians, whereas Macedonians nationalists claim the figures are more like 120,000-350,000.[citation needed] In Bulgaria, there are officially, 5,071 ethnic Macedonians, whereas Macedonian nationalists claim 200,000 [4]). In Greece, there is a Slavic-speaking minority with various self-identifications (Macedonian, Greek, Bulgarian), estimated by Ethnologue, and the Greek Helsinki Monitor as being between 100,000-200,000 (according to the Greek Helsinki Monitor only an estimated 10,000-30,000 have an ethnic Macedonian national identity [5]). Macedonian nationalists have claimed that there is a Macedonian minority numbering up to 800,000.[citation needed]

The roots of the concept can be traced back to 1910. One of the main platforms from the First Balkan Socialist Conference in 1910 was the solution to the Macedonian Question, Georgi Dimitrov in 1915 writes that the creation of a "Macedonia, which was split into three parts, was to be reunited into a single state enjoying equal rights within the framework of the Balkan Democratic Federation".[6]

The concept about United Macedonia was used by revolutionaries from the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) too. In 1920-1934 their leaders - Todor Alexandrov, Aleksandar Protogerov, Ivan Mihailov, etc., accept this concept with the aim to liberate the territories occupied by Serbia and Greece and to create Independent and United Macedonia for all Macedonians - Bulgarians, Greeks, Serbians, Albanians, etc. Bulgarian government of Alexander Malinov in 1918 offered to give Pirin Macedonia to such a United Macedonia after World War One[7], but the Great Powers did not adopted this idea, because Serbia and Greece opposed. Bulgarian government again in 1945 offered to give Pirin Macedonia to such a United Macedonia after World War Two.[citation needed]

The idea of a United Macedonia under Communist rule was abandoned in 1948 when the Greek Communists lost in the Greek Civil War, and Tito fell out with the Soviet Union and pro-Soviet Bulgaria.

Before and just after the Republic of Macedonia's independence, it was assumed in Greece that the ideology of a United Macedonia was still state-sponsored. In the first constitution of the newly independent Republic of Macedonia, adopted on 17 November 1991, Article 47 read as follows [8]:

- (1) The Republic cares for the status and rights of those persons belonging to the Macedonian people in neighboring countries, as well as Macedonian expatriates, assists their cultural development and promotes links with them. In the exercise of this concern the Republic will not interfere in the sovereign rights of other states or in their internal affairs.

- (2) The Republic cares for the cultural, economic and social rights of the citizens of the Republic abroad.

This was seen in Greece as a declaration of a right to interfere in Greece's internal affairs.[citation needed]

Finally, on 13 September 1995, the Republic of Macedonia signed an Interim Accord with Greece [9] in order to end the economic embargo Greece had imposed, amongst other reasons, for the perceived land claims. Amongst its provisions, the Accord specified that Macedonia would renounce all land claims to neighboring states' territories.

The United Macedonia concept is still found among official sources in the Republic,[1][4][10][11] and taught in schools through school textbooks and through other governmental publications.[12][13][14]

See also

- Macedonia (terminology)

- Demographic history of Macedonia

- Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization

- History of the Republic of Macedonia

- Macedonism

- The Ten Lies of Macedonism

- Titoism

References

- ^ a b Greek Macedonia "not a problem", The Times (London), August 5, 1957

- ^ The Balkans. From Constantinople to Communism. Dennis P Hupchik, page 299

- ^ The Macedoine, "The National Question in Yugoslavia. Origins, History, Politics", by Ivo Banac, Cornell University Press, 1984.

- ^ a b See [1]. Cite error: The named reference "Bulgaria" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ See [2].

- ^ "The Significance of the Second Balkan Conference". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2009-05-21.

- ^ Gerginov, Kr., Bilyarski, Ts. Unpublished documents for Todor Alexandrov's activities 1910-1919, magazine VIS, book 2, 1987, p.214 - Гергинов, Кр. Билярски, Ц. Непубликувани документи за дейността на Тодор Александров 1910-1919, сп. ВИС, кн. 2 от 1987, с. 214.

- ^ Constitution of the Republic of Macedonia, adopted 17 November 1991, amended on 6 January 1992.

- ^ "Interim Accord between the Hellenic Republic and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia", United Nations, 13 September 1995.

- ^ Simons, Marlise (February 3, 1992). "As Republic Flexes, Greeks Tense Up". New York Times.

- ^ Danforth, Loring M. How can a woman give birth to one Greek and one Macedonian?. Retrieved 2006-12-26.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Facts About the Republic of Macedonia - annual booklets since 1992, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia Secretariat of Information, Second edition, 1997, ISBN 9989-42-044-0. p.14. 2 August 1944.

- ^ "Official site of the Embassy of the Republic of Macedonia in London". An outline of Macedonian history from Ancient times to 1991. Retrieved 2006-12-26.

- ^ Macedonianism: FYROM'S expansionist designs against Greece after the Interim Accord (1995), Society for Macedonian Studies, Ephesus Publishing, 2007