Tomohiro Nishikado: Difference between revisions

RjwilmsiBot (talk | contribs) m fixing page range dashes using AWB (7840) |

→Speed Race: re-word |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

===''Speed Race''=== |

===''Speed Race''=== |

||

{{redirect|Speed Race|the anime and manga franchise|Speed Racer}} |

|||

| ⚫ | 1974 saw the release of Nishikado's '' |

||

| ⚫ | 1974 saw the release of Nishikado's ''Speed Race'', an early black-and-white car [[racing video game]],<ref name="Kohler-16"/> which he considers to be "the first [[Arcade game|arcade]] driving game, and possibly the first Japanese game in America (distributed by Midway)."<ref>{{cite web|date=May 6, 2009|title=Interview: 'Space Invaders' creator Tomohiro Nishikado|work=[[USA Today]]|url=http://content.usatoday.com/communities/gamehunters/post/2009/05/66479041/1|accessdate=2011-03-22}}</ref> The game's most important innovations were its introductions of [[collision detection]], where [[Sprite (computer graphics)|sprites]] could collide with each other, and [[scrolling]] graphics, where the sprites moved along a vertical scrolling [[Overhead perspective|overhead]] track,<ref name=Barton-197>Bill Loguidice & Matt Barton (2009), ''Vintage games: an insider look at the history of Grand Theft Auto, Super Mario, and the most influential games of all time'', p. 197, [[Focal Press]], ISBN 0240811461</ref> with the course width becoming wider or narrower as the player's car moves up the road, while the player races against other [[Artificial intelligence|rival cars]], more of which appear as the [[Score (game)|score]] increases. The faster the player's car drives, the more the score increases.<ref name="Speed-Race">{{KLOV game|id=9709|name=Speed Race}}</ref> |

||

In contrast to the [[Paddle (game controller)|volume-control dials]] used for ''Pong'' machines at the time, ''Speed Race'' introduced a realistic [[racing wheel]] [[Game controller|controller]],<ref name="Kohler-16"/> which included an [[Throttle|accelerator]], [[gear shift]], [[speedometer]], and [[tachometer]]. It could be played in either single-player or alternating two-player, where each player attempts to beat the other's score. The game also featured an early example of [[difficulty level]]s, giving players an option between "Beginner's race" and "Advanced player's race".<ref name="Speed-Race"/> The game was re-branded as ''Racer'' by [[Midway Games]] for released in the United States and was influential on later racing games,<ref name=Barton-197/> including [[Atari]] titles such as ''Highway'' in 1975 and ''[[Night Driver]]'' in 1976.<ref>Bill Loguidice & Matt Barton (2009), ''Vintage games: an insider look at the history of Grand Theft Auto, Super Mario, and the most influential games of all time'', pp. 197-8, [[Focal Press]], ISBN 0240811461</ref> |

|||

===''Western Gun / Gun Fight''=== |

===''Western Gun / Gun Fight''=== |

||

| Line 25: | Line 29: | ||

===''Interceptor''=== |

===''Interceptor''=== |

||

Nishikado's next title was '' |

Nishikado's next title was ''Interceptor'', released in Japan in 1975<ref name="Dreams"/> and abroad in 1976. It was an early [[first-person shooter]] and [[combat flight simulator]] that involved piloting a [[Fighter aircraft|jet fighter]], using an eight-way joystick to aim with a crosshair and shoot at enemy aircraft that move in formations of two, can [[2.5D|scale in size]] depending on their distance to the player, and can move out of the player's firing range.<ref name="Interceptor">{{KLOV game|8195|Interceptor}}</ref> |

||

===''Space Invaders''=== |

===''Space Invaders''=== |

||

| Line 41: | Line 45: | ||

His company Dreams is also credited for ''[[Chase H.Q.|Chase HQ: Secret Police]]'' published by [[Metro3D, Inc.|Metrod3D]] for the [[Game Boy Color]] in 1999, the [[3D computer graphics|3D]] [[eroge]] [[visual novel]] ''Dancing Cats'' published by [[Illusion (company)|Illusion]] for the [[Personal computer|PC]] in 2000, ''[[Super Bust-A-Move]]'' (''Super Puzzle Bobble'') published by Taito for the [[PlayStation 2]] in 2000, ''[[Rainbow Islands: The Story of Bubble Bobble 2|Rainbow Islands]]'' (''Bubble Bobble 2'') and ''[[Shaun Palmer's Pro Snowboarder]]'' for the Game Boy Color in 2001, and the 2008 [[Nintendo DS]] version of ''[[Ys I & II]]''.<ref name="Moby-Dreams">{{cite web|title=Dreams Co., Ltd.|publisher=[[MobyGames]]|url=http://www.mobygames.com/company/dreams-co-ltd|accessdate=2011-03-27}}</ref> He personally oversaw the development of ''[[Space Invaders Revolution]]'', released by Taito in 2005,<ref name="IGN-Revolution">{{cite web| url = http://ds.ign.com/articles/646/646799p1.html| title = Space Invaders Revolution| publisher = IGN| date = 2005-08-30| first = Craig| last = Harris| accessdate = 2010-06-18}}</ref> and was involved in the development of ''[[Space Invaders Infinity Gene]]'', released by Taito's current owner [[Square Enix]] in 2008.<ref name="Moby"/> His company Dreams was involved in the development of the [[fighting game]] ''[[Battle Fantasia]]'', released by [[Arc System Works]] in 2008.<ref name="Moby-Dreams"/> |

His company Dreams is also credited for ''[[Chase H.Q.|Chase HQ: Secret Police]]'' published by [[Metro3D, Inc.|Metrod3D]] for the [[Game Boy Color]] in 1999, the [[3D computer graphics|3D]] [[eroge]] [[visual novel]] ''Dancing Cats'' published by [[Illusion (company)|Illusion]] for the [[Personal computer|PC]] in 2000, ''[[Super Bust-A-Move]]'' (''Super Puzzle Bobble'') published by Taito for the [[PlayStation 2]] in 2000, ''[[Rainbow Islands: The Story of Bubble Bobble 2|Rainbow Islands]]'' (''Bubble Bobble 2'') and ''[[Shaun Palmer's Pro Snowboarder]]'' for the Game Boy Color in 2001, and the 2008 [[Nintendo DS]] version of ''[[Ys I & II]]''.<ref name="Moby-Dreams">{{cite web|title=Dreams Co., Ltd.|publisher=[[MobyGames]]|url=http://www.mobygames.com/company/dreams-co-ltd|accessdate=2011-03-27}}</ref> He personally oversaw the development of ''[[Space Invaders Revolution]]'', released by Taito in 2005,<ref name="IGN-Revolution">{{cite web| url = http://ds.ign.com/articles/646/646799p1.html| title = Space Invaders Revolution| publisher = IGN| date = 2005-08-30| first = Craig| last = Harris| accessdate = 2010-06-18}}</ref> and was involved in the development of ''[[Space Invaders Infinity Gene]]'', released by Taito's current owner [[Square Enix]] in 2008.<ref name="Moby"/> His company Dreams was involved in the development of the [[fighting game]] ''[[Battle Fantasia]]'', released by [[Arc System Works]] in 2008.<ref name="Moby-Dreams"/> |

||

==See also== |

|||

*[[List of Taito games]] |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 00:29, 25 September 2011

Tomohiro Nishikado (西角 友宏, Nishikado Tomohiro, born March 31, 1944 in Osaka) is a Japanese video game developer. He is best known as the creator of the shooter game, Space Invaders, released to the public in 1978 by the Taito Corporation of Japan, often credited as the first shoot 'em up[1] and for beginning the golden age of video arcade games.[2]

Originally Nishikado wanted to use airplanes as enemies for Space Invaders, but would have encountered problems making them move smoothly due to the limited computing power at the time (the game was based on Intel's 8 bit 8080 microprocessor). Humans would have been easier to render, but management at Taito forbade the use of human targets.

Prior to Space Invaders, he was also the designer for many of Taito's earlier hits, including the early team sport games Soccer and Davis Cup in 1973, the early scrolling racing video game Speed Race in 1974,[3] the early dual-stick on-foot multi-directional shooter[4] Western Gun (Gun Fight) in 1975,[5] and the first-person combat flight simulator Interceptor[6] in 1975.[7]

Biography

Nishikado graduated with an engineering degree from Tokyo Denki University in 1968. He joined Taito Trading Company in 1969. After working on mechanical games, in 1972, he developed Elepong (similar to Pong), one of Japan's earliest locally-produced video arcade games, released in 1973. He produced over 10 video games before Space Invaders was released in 1978. He left Taito in 1996 to found his own company, Dreams.[7][8]

Davis Cup and Soccer

His first original titles included the sports games Davis Cup and Soccer, both released in 1973.[3] Davis Cup was an early team sport video game, a tennis doubles game with similar ball-and-paddle gameplay to Pong but played in doubles,[9] allowing up to four players to compete.[3] Soccer was also an early team sport video game,[3] and an early video game to be based on football, specifically association football. Soccer was also a ball-and-paddle game, but with a green background to simulate a playfield, allowed each player to control both a forward and a goalkeeper, and let them adjust the size of the players who were represented as paddles on screen.[10] Nishikado claims Soccer to be "Japan's first video game" released.[7]

Speed Race

1974 saw the release of Nishikado's Speed Race, an early black-and-white car racing video game,[3] which he considers to be "the first arcade driving game, and possibly the first Japanese game in America (distributed by Midway)."[11] The game's most important innovations were its introductions of collision detection, where sprites could collide with each other, and scrolling graphics, where the sprites moved along a vertical scrolling overhead track,[12] with the course width becoming wider or narrower as the player's car moves up the road, while the player races against other rival cars, more of which appear as the score increases. The faster the player's car drives, the more the score increases.[13]

In contrast to the volume-control dials used for Pong machines at the time, Speed Race introduced a realistic racing wheel controller,[3] which included an accelerator, gear shift, speedometer, and tachometer. It could be played in either single-player or alternating two-player, where each player attempts to beat the other's score. The game also featured an early example of difficulty levels, giving players an option between "Beginner's race" and "Advanced player's race".[13] The game was re-branded as Racer by Midway Games for released in the United States and was influential on later racing games,[12] including Atari titles such as Highway in 1975 and Night Driver in 1976.[14]

Western Gun / Gun Fight

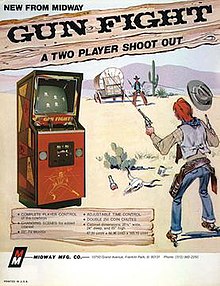

His next major title was Western Gun (known as Gun Fight in the United States), released in 1975,[15] which is historically significant for several reasons.[16] It was an early on-foot, multi-directional shooter,[17] that could be played in single-player or two-player. It also introduced video game violence, being the first video game to depict human-to-human combat,[18] and the first to depict a gun on screen.[17]

The game introduced dual-stick controls,[19] with one eight-way joystick for movement and the other for changing the shooting direction,[17][20] and was the first known video game to feature game characters and fragments of story through its visual presentation.[15] The player characters used in the game represented avatars for the players,[18] and would yell "Got me!" when one of them is shot.[21] Other features of the game included obstacles such as a cactus,[22] and in later levels, pine trees and moving wagons, that can provide cover for the players and are destructible. The guns have limited ammunition, with each player limited to six bullets,[16] and shots can ricochet off the top or bottom edges of the playfield, allowing for indirect hits to be used as a strategy.[16][22]

Western Gun was his second game licensed to Midway for release in the United States. However, the title was changed to Gun Fight for its American release.[23] Midway's Gun Fight adaptation was itself notable for being the first video game to use a microprocessor.[24] Nishikado believed that his original version was more fun, but was impressed with the improved graphics and smoother animation of Midway's version.[21] This led him to design microprocessors into his subsequent games.[15] Gun Fight was a success in the arcades,[18][25] was later ported to the Bally Astrocade console[18] and several computer platforms.[16][26] Gun Fight's success opened the way for Japanese video games in the American market.[24]

Interceptor

Nishikado's next title was Interceptor, released in Japan in 1975[7] and abroad in 1976. It was an early first-person shooter and combat flight simulator that involved piloting a jet fighter, using an eight-way joystick to aim with a crosshair and shoot at enemy aircraft that move in formations of two, can scale in size depending on their distance to the player, and can move out of the player's firing range.[6]

Space Invaders

In 1977, Nishikado began developing Space Invaders, which he created entirely on his own. In addition to designing and programming the game, he also did the artwork and sounds, and engineered the game's arcade hardware, putting together a microcomputer from scratch. Following its release in 1978, Space Invaders went on to become his most successful video game.[27] It is frequently cited as the "first" or "original" in the shoot 'em up genre,[1][28][29] and was responsible for making the shooter game genre become prolific. Space Invaders pitted the player against multiple enemies descending from the top of the screen at a constantly increasing rate of speed.[29] The game used alien creatures inspired by The War of the Worlds because the developers were unable to render the movement of aircraft; in turn, the aliens replaced human enemies because of moral concerns (regarding the portrayal of killing humans) on the part of Taito. As with subsequent shoot 'em ups of the time, the game was set in space as the available technology only permitted a black background. The game also introduced the idea of giving the player a number of "lives". Space Invaders was a massive commercial success, causing a coin shortage in Japan.[30][31] It sold over 360,000 arcade cabinets worldwide,[32] and by 1981 had grossed more than $1 billion (four billion quarters),[33] equivalent to $2.5 billion in 2011.[34]

As one of the earliest shooter games, it set precedents and helped pave the way for future titles and for the shooting genre.[35][36] Space Invaders popularized a more interactive style of gameplay with the enemies responding to the player controlled cannon's movement.[37] It was also the first video game to popularize the concept of achieving a high score,[38][39][35] being the first game to save the player's score.[35] It was also the first game where players had to repel hordes of creatures,[27] take cover from enemy fire, and use destructible barriers,[40] in addition to being the first game to use a continuous background soundtrack, with four simple chromatic descending bass notes repeating in a loop, though it was dynamic and changed pace during stages.[41] It also moved the gaming industry away from Pong-inspired sports games grounded in real-world situations towards action games involving fantastical situations.[42] Space Invaders set the template for the shoot 'em up genre,[42] with its influence extending to most shooting games released to the present day,[27] including first-person shooters such as Wolfenstein,[43][44] Doom,[45] Halo[46] and Call of Duty.[47]

Game designer Shigeru Miyamoto considers Space Invaders a game that revolutionized the video game industry; he was never interested in video games before seeing it, and it would inspire him to produce video games.[48] Several publications ascribe the expansion of the video game industry from a novelty into a global industry to the success of the game, attributing the shift of video games from bars and arcades to more mainstream locations like restaurants and department stores to Space Invaders.[49] The game's success is also credited for ending the video game crash of 1977 and beginning the golden age of video arcade games.[2] The launch of the arcade phenomenon in North America was in part due to Space Invaders.[50] Game Informer considers it, along with Pac-Man, one of the most popular arcade games that tapped into popular culture and generated excitement during the golden age of arcades.[51] The game also played an important role during the second generation of consoles, when it became the Atari 2600's first killer app, establishing Atari as the market leader in the home video game market at the time.[27] Space Invaders is today regarded as one of the most influential video games of all time.[35]

Later career

Nishikado's later credited games for Taito included the racing video game Chase HQ II: Special Criminal Investigation in 1989, the scrolling shooters Darius II (Sagaia) in 1989 and Darius Twin in 1991, the platform game Parasol Stars: The Story of Bubble Bobble III in 1991, the SNES role-playing video game Lufia & the Fortress of Doom in 1993, the beat 'em up Sonic Blast Man II in 1994, and the puzzle game Bust-A-Move 2 (Puzzle Bobble 2) in 1995. Under his own company Dreams, his credited games include Bust-A-Move Millennium, published by Acclaim Entertainment in 2000.[52]

His company Dreams is also credited for Chase HQ: Secret Police published by Metrod3D for the Game Boy Color in 1999, the 3D eroge visual novel Dancing Cats published by Illusion for the PC in 2000, Super Bust-A-Move (Super Puzzle Bobble) published by Taito for the PlayStation 2 in 2000, Rainbow Islands (Bubble Bobble 2) and Shaun Palmer's Pro Snowboarder for the Game Boy Color in 2001, and the 2008 Nintendo DS version of Ys I & II.[53] He personally oversaw the development of Space Invaders Revolution, released by Taito in 2005,[54] and was involved in the development of Space Invaders Infinity Gene, released by Taito's current owner Square Enix in 2008.[52] His company Dreams was involved in the development of the fighting game Battle Fantasia, released by Arc System Works in 2008.[53]

See also

References

- ^ a b Game Genres: Shmups, Professor Jim Whitehead, January 29, 2007, Accessed June 17, 2008

- ^ a b Whittaker, Jason (2004). The Cyberspace Handbook. Routledge. p. 122. ISBN 041516835X.

- ^ a b c d e f Chris Kohler (2005), [[Power-Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life]], BradyGames, p. 16, ISBN 0744004241, retrieved 2011-03-27

{{citation}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ Stephen Totilo, In Search Of The First Video Game Gun, Kotaku

- ^ Chris Kohler (2005), Power-Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life, p. 19, BradyGames, ISBN 0744004241

- ^ a b Interceptor at the Killer List of Videogames

- ^ a b c d "Tomohiro Nishikado's biography at his company's web site". Dreams, Inc. Archived from the original on 2009-04-01. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ^ "Survey of Digital Games: Home Pong to Late 70s arcade" (slide 28).

- ^ Davis Cup at the Killer List of Videogames

- ^ Soccer, Killer List of Videogames

- ^ "Interview: 'Space Invaders' creator Tomohiro Nishikado". USA Today. May 6, 2009. Retrieved 2011-03-22.

- ^ a b Bill Loguidice & Matt Barton (2009), Vintage games: an insider look at the history of Grand Theft Auto, Super Mario, and the most influential games of all time, p. 197, Focal Press, ISBN 0240811461

- ^ a b Speed Race at the Killer List of Videogames

- ^ Bill Loguidice & Matt Barton (2009), Vintage games: an insider look at the history of Grand Theft Auto, Super Mario, and the most influential games of all time, pp. 197-8, Focal Press, ISBN 0240811461

- ^ a b c Chris Kohler (2005), [[Power-Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life]], BradyGames, p. 18, ISBN 0744004241, retrieved 2011-03-27

{{citation}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ a b c d Template:Allgame

- ^ a b c Stephen Totilo (August 31, 2010). "In Search Of The First Video Game Gun". Kotaku. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ^ a b c d Shirley R. Steinberg (2010), Shirley R. Steinberg, Michael Kehler, Lindsay Cornish (ed.), Boy Culture: An Encyclopedia, vol. 1, ABC-CLIO, p. 451, ISBN 0313350809, retrieved 2011-04-02

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Brian Ashcraft & Jean Snow (2008), Arcade Mania: The Turbo-charged World of Japan's Game Centers, Kodansha International, ISBN 4770030789

- ^ Western Gun at the Killer List of Videogames

- ^ a b Chris Kohler (2005), [[Power-Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life]], BradyGames, p. 19, ISBN 0744004241, retrieved 2011-03-27

{{citation}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ a b Rusel DeMaria & Johnny L. Wilson (2003), High score! The illustrated history of electronic games (2 ed.), McGraw-Hill Professional, pp. 24–5, ISBN 0072231726, retrieved 2011-04-02

- ^ Chris Kohler (2005), Power-Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life, p. 211, BradyGames, ISBN 0744004241

- ^ a b Steve L. Kent (2001), The ultimate history of video games: from Pong to Pokémon and beyond : the story behind the craze that touched our lives and changed the world, p. 64, Prima, ISBN 0761536434

- ^ I. M. Stoned (2009), Weed: 420 Things You Didn't Know (Or Remember) About Cannabis, Adams Media, p. 158, ISBN 1440503494, retrieved 2011-04-02,

Before you assume it required you to type things in like "Go North" or "Examine Corpse," you should know that Gun Fight was the Halo of its day.

- ^ "Atarimania - Arcade Classics: Sea Wolf II / Gun Fight". Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ^ a b c d Edwards, Benj. "Ten Things Everyone Should Know About Space Invaders". 1UP.com. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ^ Bielby, Matt, "The Complete YS Guide to Shoot 'Em Ups", Your Sinclair, July, 1990 (issue 55), p. 33

- ^ a b Buchanan, Levi, Space Invaders, IGN, March 31, 2003, Accessed June 14, 2008

- ^ Ashcraft pp. 72–73

- ^ Design your own Space Invaders, Science.ie, 4 March 2008, Accessed 17 June 2008

- ^ Jiji Gaho Sha, inc. (2003), Asia Pacific perspectives, Japan, vol. 1, University of Virginia, p. 57, retrieved 2011-04-09,

At that time, a game for use in entertainment arcades was considered a hit if it sold 1000 units; sales of Space Invaders topped 300,000 units in Japan and 60,000 units overseas.

- ^ Glinert, Ephraim P. (1990), Visual Programming Environments: Applications and Issues, IEEE Computer Society Press, p. 321, ISBN 0818689749, retrieved 2011-04-10,

As of mid-1981, according to Steve Bloom, author of Video Invaders, more than four billion quarters had been dropped into Space Invaders games around the world

- ^ "CPI Inflation Calculator". Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved 2011-03-22.

- ^ a b c d Geddes, Ryan (2007-12-10). "IGN's Top 10 Most Influential Games". IGN. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Craig Glenday, ed. (2008-03-11). "Record Breaking Games: Shooting Games". Guinness World Records Gamer's Edition 2008. Guinness World Records. Guinness. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-904994-21-3.

- ^ Retro Gamer Staff. "Nishikado-San Speaks". Retro Gamer (3). Live Publishing: 35.

- ^ Kevin Bowen. "The Gamespy Hall of Fame: Space Invaders". GameSpy. Retrieved 2010-01-27.

- ^ Craig Glenday, ed. (2008-03-11). "Record Breaking Games: Shooting Games Roundup". Guinness World Records Gamer's Edition 2008. Guinness World Records. Guinness. pp. 106–107. ISBN 978-1-904994-21-3.

- ^ Brian Ashcraft (January 20, 2010). "How Cover Shaped Gaming's Last Decade". Kotaku. Retrieved 2011-03-26.

- ^ Karen Collins (2008), From Pac-Man to pop music: interactive audio in games and new media, Ashgate, p. 2, ISBN 0754662004

- ^ a b "Essential 50: Space Invaders". 1UP.com. Retrieved 2011-03-26.

- ^ Ronald Strickland (2002), Growing up postmodern: neoliberalism and the war on the young, Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 112–3, ISBN 0742516512, retrieved 2011-04-10

- ^ James Paul Gee (2004), What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy, Palgrave Macmillan, p. 47, ISBN 1403965382, retrieved 2011-04-10

- ^ Frans Mäyrä (2008), An introduction to games studies: games in culture, SAGE, p. 104, ISBN 1412934451, retrieved 2011-04-10,

The gameplay of Doom is at its core familiar from the early classics like Space Invaders ... it presents the player with the clear and simple challenge of surviving while shooting everything that moves.

- ^ Steven Edward Jones (2008). The meaning of video games: gaming and textual studies. Taylor & Francis. pp. 84–5. ISBN 041596055X. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

The developers of Halo are aware of their own place in gaming history, and one of them once joked that their game could be seen as "Space Invaders in a tube." The joke contains a double-edged insight: on the one hand, Halo is first and finally about shooting aliens; on the other hand, even the 1978 2-D arcade shooter, Space Invaders, designed by Tomohiro Nishikado for the company Taito, is more interesting than that would suggest.

- ^ Simon Carles (November 16, 2010). "No More Russian - Infinity Ward's Modern Warfare 2, One Year On". GameSetWatch. Retrieved 2011-04-09.

- ^ Sayre, Carolyn (2007-07-19). "10 Questions for Shigeru Miyamoto". Time. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Edge Staff (2007-08-13). "The 30 Defining Moments in Gaming". Edge. Future plc. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ^ Buchanan, Levi (2008-04-08). "Top 10 Classic Shoot 'Em Ups". IGN. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

- ^ "Classic GI: King of the Hill". Game Informer (178). Cathy Preston: 108. 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Tomohiro Nishikado at MobyGames

- ^ a b "Dreams Co., Ltd". MobyGames. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ^ Harris, Craig (2005-08-30). "Space Invaders Revolution". IGN. Retrieved 2010-06-18.

External links

- Article at The Dot Eaters, on Nishikado and a history of Space Invaders.

- Partial list of games credited to Nishikado.