Shawnee: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 72.250.135.92 (talk) to last version by ClueBot NG |

→Shawnee in Ohio and other states: Addition of the Ridgetop Shawnee |

||

| Line 212: | Line 212: | ||

* the East of the River Shawnee, |

* the East of the River Shawnee, |

||

* the Piqua Shawnee Tribe |

* the Piqua Shawnee Tribe |

||

* [[Ridgetop Shawnee]] - [[Kentucky]] - In 2009 and 2010, the State House of the [[Kentucky General Assembly]] recognized the Ridgetop Shawnee Tribe of Indians by passing, unopposed, House Joint Resolutions 15 or HJR-15 in 2009 and HJR-16 in 2010. <ref>{{cite web|title=Kentucky General Assembly 2010 Regular Session HJR-16|url= http://www.lrc.ky.gov/record/10rs/HJ16.htm|publisher=kentucky.gov, updated 9-2-2010}}</ref> <ref>{{cite web|title=Kentucky General Assembly 2009 Regular Session HJR-15|url= http://www.lrc.ky.gov/record/09rs/HJ15.htm|publisher=kentucky.gov, updated 5-2-2009}}</ref>. |

|||

These bands are not [[Federally recognized tribes|federally recognized]], though some legal scholars dispute the formality of this recognition.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.westgov.org/wga/meetings/gaming/watson-ohio.pdf |format=PDF|title=Indian Gambling in Ohio:What are the Odds? |accessdate=2007-09-30 |last=Watson |first=Blake A. |work=Capital University Law Review 237 (2003) (excerpts) |quote=Ohio in any event does not officially recognize Indian tribes. }} Watson cites legal opinions that the resolution by the Ohio Legislature recognizing the United Remnant Band of the Shawnee Nation was ceremonial and did not grant legal status as a tribe. Confirmation of the Remnant Bands recognition is referred to and presented to the Bureau of Indian Affairs and The President of the United States in 1981.</ref> |

These bands are not [[Federally recognized tribes|federally recognized]], though some legal scholars dispute the formality of this recognition.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.westgov.org/wga/meetings/gaming/watson-ohio.pdf |format=PDF|title=Indian Gambling in Ohio:What are the Odds? |accessdate=2007-09-30 |last=Watson |first=Blake A. |work=Capital University Law Review 237 (2003) (excerpts) |quote=Ohio in any event does not officially recognize Indian tribes. }} Watson cites legal opinions that the resolution by the Ohio Legislature recognizing the United Remnant Band of the Shawnee Nation was ceremonial and did not grant legal status as a tribe. Confirmation of the Remnant Bands recognition is referred to and presented to the Bureau of Indian Affairs and The President of the United States in 1981.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 19:23, 30 January 2012

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Oklahoma[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Shawnee, English | |

| Religion | |

| traditional beliefs and Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Sac and Fox (Mesquakie) |

The Shawnee, Shaawanwaki, Shaawanooki and Shaawanowi lenaweeki,[2] are an Algonquian-speaking people native to North America. Historically they inhabited the areas of Ohio, Virginia, West Virginia, Western Maryland, Kentucky, Indiana, and Pennsylvania. Today there are three federally recognized Shawnee tribes: Absentee-Shawnee Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma, Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, and Shawnee Tribe, all of which are headquartered in Oklahoma.

History

Many thousands of years ago groups known as Paleo-Indians lived in what today is referred to as the American Midwest. These groups were hunter-gatherers who hunted a wide range of animals, including the megafauna, which became extinct following the end of the Pleistocene age. Scholars believe that Paleo-Indians were specialized, highly mobile foragers who hunted late Pleistocene fauna such as bison, mastodons, caribou, and mammoths.

Shawnee mound builder origins

Some scholars believe that the Shawnee are descendants of the people of the prehistoric Fort Ancient culture of the Ohio country, although this is not universally accepted.[3][4][5] Fort Ancient flourished from 1000–1650 CE among a people who predominantly inhabited land along the Ohio River in areas of southern modern-day Ohio, northern Kentucky and western West Virginia. The Fort Ancient culture was once thought to have been an expansion of the Mississippian culture. Scholars now believe it developed independently and was descended from the Hopewell culture (100 BCE – 500 CE), also a mound builder people.

The group of cultures collectively called Mound Builders were succeeding prehistoric societies in North America who constructed various styles of complex, massive earthworks: earthen mounds for burial, elite residential and ceremonial purposes. These included the Pre-Columbian cultures of the Archaic period; Woodland period (Adena and Hopewell cultures); and Mississippian period; dating from roughly 3000 BCE to the 16th century CE, and living in regions of the Great Lakes, the Ohio River valley, and the Mississippi River valley and its tributaries, extending into the Southeast of the present-day United States.[6]

Uncertainty surrounds the eventual fate of the Fort Ancient people. Most likely their society, like the Mississippian culture to the south, was severely disrupted by waves of epidemics from new infectious diseases carried by the very first Spanish explorers in the 16th century.[7] After 1525 at the Madisonville-type site, the village's house size becomes smaller and fewer with evidence to be "a less horticulture-centered, sedentary way of life".[8][9] There is a gap in the archaeological record between the most recent Fort Ancient sites and the oldest sites of the Shawnee, who occupied the area at the time of later European (French and English) explorers. It is generally accepted that similarities in material culture, art, mythology, and Shawnee oral history linking them to the Fort Ancients can be used to establish the shift of Fort Ancient society into historical Shawnee society.[10]

The Shawnee traditionally considered the Lenape (or Delaware) their "grandfathers". The Algonquian nations of present-day Canada regarded the Shawnee as their southernmost branch. Along the East Coast, the Algonquian-speaking tribes were mostly located in coastal areas, from Quebec to the Carolinas. Algonquian languages have words similar to the archaic shawano (now: shaawanwa) meaning "south". However, the stem shaawa- does not mean "south" in Shawnee, but "moderate, warm (of weather)". In one Shawnee tale, Shaawaki is the deity of the south.

Shawnee after 1600

Europeans reported encountering Shawnee over a widespread geographic area. The earliest mention of the Shawnee may be a 1614 Dutch map showing the Sawwanew just east of the Delaware River. Later 17th-century Dutch sources also place them in this general location. Accounts by French explorers in the same century usually located the Shawnee along the Ohio River, where they encountered them on forays from Canada and the Illinois Country.[11]

According to one legend, the Shawnee were descended from a party sent by Chief Opechancanough, ruler of the Powhatan Confederacy 1618–1644, to settle in the Shenandoah Valley. The party was led by his son, Sheewa-a-nee.[12] Edward Bland, an explorer who accompanied Abraham Wood's expedition in 1650, wrote that in Opechancanough's day, there had been a falling-out between the "Chawan" chief and the weroance of the Powhatan (also a relative of Opechancanough's family). He said the latter had murdered the former.[13] Explorers Batts and Fallam in 1671 reported that the Shawnee were contesting the Shenandoah Valley with Iroquois in that year, and were losing. By the time European-American settlers began to arrive in the Valley (c. 1730), the Iroquois had departed. The Shawnee were then the sole residents of the northern part of the valley.

Sometime before 1670, a group of Shawnee migrated to the Savannah River area. The English based in Charles Town, South Carolina were contacted by these Shawnee in 1674. They forged a long-lasting alliance. The Savannah River Shawnee were known to the Carolina English as "Savannah Indians". Around the same time, other Shawnee groups migrated to Florida, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and other regions south and east of the Ohio country.

Historian Alan Gallay speculates that the Shawnee migrations of the middle to late 17th century were probably driven by the Iroquois Wars that began in the 1640s. The Shawnee became known for their widespread settlements from modern Illinois and New York to Georgia. Among their known villages were Eskippakithiki, Sonnionto, and Suwanee, Georgia. Their language became a lingua franca for trade among numerous tribes. They became leaders among the tribes, initiating and sustaining pan-Indian resistance to European and Euro-American expansion.[14]

Prior to 1754, the Shawnee had a headquarters at Shawnee Springs at modern-day Cross Junction, Virginia near Winchester. The father of the later chief Cornstalk held his court there. Two other Shawnee villages existed in the Shenandoah Valley: one at Moorefield, West Virginia, and one on the North River. In 1753, Shawnee to the west sent messengers inviting the Virginia people to leave the Shenandoah Valley and cross the Alleghenies. The Virginia Shawnee migrated west the following year,[15][16] joining Shawnee on the Scioto River in the Ohio country.

After the Beaver Wars, the Iroquois claimed the Ohio Country as their hunting ground by right of conquest, and treated the Shawnee and Delaware who resettled there as dependent tribes. Some independent Iroquois bands from various tribes also migrated westward, where they became known in Ohio as the Mingo. These three tribes—the Shawnee, the Delaware, and the Mingo—then became closely associated with one another, despite the differences in their languages. The first two were Algonguian speaking and the third Iroquoian.

Sixty Years' War

After the Battle of the Monongahela in 1755, many Shawnee fought as allies of their trading partners the French during the early years of the French and Indian War (aka Seven Years War).[17] In 1758 they settled with the British colonists, signing the Treaty of Easton in 1758. When the British defeated the French in 1763, other Shawnee joined Pontiac's Rebellion against the British, which failed a year later.

The British issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763 during Pontiac's Rebellion, to draw a boundary line between the British colonies in the east and the Ohio Country west of the Appalachian Mountains. They were trying to settle points of conflict with the Indians and establish a reserve for them. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768, however, extended that line westwards, giving the British a claim to what is now West Virginia and Kentucky. The Shawnee did not agree to this treaty: it was negotiated between British officials and the Iroquois, who claimed sovereignty over the land, although Shawnee and other Native American tribes also hunted there.

After the Stanwix treaty, Anglo-Americans began pouring into the Ohio River Valley for settlement. Violent incidents between settlers and Indians escalated into Dunmore's War in 1774. British diplomats managed to isolate the Shawnee during the conflict: the Iroquois and the Delaware stayed neutral. The Shawnee faced the British colony of Virginia with only a few Mingo allies. Lord Dunmore, royal governor of Virginia, launched a two-pronged invasion into the Ohio Country. Shawnee Chief Cornstalk attacked one wing but fought to a draw in the only major battle of the war, the Battle of Point Pleasant.

In the Treaty of Camp Charlotte, Cornstalk and the Shawnee were compelled to recognize the Ohio River boundary established by the 1768 Stanwix treaty. Many other Shawnee leaders refused to recognize this boundary, however. When the American Revolutionary War broke out in 1776, several Shawnee chiefs advocated joining the war as British allies, hoping to drive the colonists back across the mountains. The Shawnee were divided: Cornstalk led those who wished to remain neutral, while war leaders such as Chief Blackfish and Blue Jacket fought as British allies.

After the Revolution, in the Northwest Indian War between the United States and a confederation of Native American tribes, the Shawnee combined with the Miami into a great fighting force. After the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794, most of the Shawnee bands signed the Treaty of Greenville the next year. They were forced to cede large parts of their homeland to the new United States. Other Shawnee groups rejected this treaty and migrated to Missouri, where they settled near Cape Girardeau.

Tecumseh's War and the War of 1812

The two principal adversaries in the conflict, Tecumseh and William Henry Harrison, had both been junior participants in the Battle of Fallen Timbers at the close of the Northwest Indian War in 1794. Tecumseh was not among the signers of the Treaty of Greenville that had ended the war and ceded much of present-day Ohio, long inhabited by the Shawnees and other Native Americans, to the United States. However, many Indian leaders in the region accepted the Greenville terms, and for the next ten years pan-tribal resistance to American hegemony faded.

In September 1809 William Henry Harrison invited the Pottawatomie, Lenape, Eel Rivers, and the Miami to a meeting in Fort Wayne. In the negotiations Harrison promised large subsidies and payments to the tribes if they would cede the lands he was asking for.[18] After two weeks of negotiating, the Pottawatomie leaders convinced the Miami to accept the treaty as reciprocity to the Pottawatomie who had earlier accepted treaties less advantageous to them at the request of the Miami. Finally the Treaty of Fort Wayne was signed on September 30, 1809, selling the United States over 3,000,000 acres (approximately 12,000 km²), chiefly along the Wabash River north of Vincennes.[18]

Tecumseh was outraged by the Treaty of Fort Wayne, and thereafter he emerged as a prominent political leader. Tecumseh revived an idea advocated in previous years by the Shawnee leader Blue Jacket and the Mohawk leader Joseph Brant, which stated that American Indian land was owned in common by all tribes, and thus no land could be sold without agreement by all. Tecumseh knew that such "broad consensus was impossible", but that is why he supported the position.[19] Not yet ready to confront the United States directly, Tecumseh's primary adversaries were initially the Native American leaders who had signed the treaty, and he threatened to kill them all.[19]

Tecumseh began to expand on his brother's teachings that called for the tribes to return to their ancestral ways, and began to connect the teachings with idea of a pan-tribal alliance. Tecumseh began to travel widely, urging warriors to abandon the accommodationist chiefs and to join the resistance at Prophetstown.[19]

Harrison was impressed by Tecumseh and even referred to him in one letter as "one of those uncommon geniuses."[19] Harrison thought that Tecumseh had the potential to create a strong empire if he went unchecked. Harrison suspected that he was behind attempts to start an uprising, and feared that if he was able to achieve a larger tribal federation, the British would take advantage of the situation to press their claims to the Northwest.[20]

In August 1810 Tecumseh and 400 armed warriors traveled down the Wabash River to meet with Harrison in Vincennes. The warriors were all wearing war paint, and their sudden appearance at first frightened the soldiers at Vincennes. The leaders of the group were escorted to Grouseland were they met Harrison. Tecumseh insisted that the Fort Wayne treaty was illegitimate; he asked Harrison to nullify it and warned that Americans should not attempt to settle the lands sold in the treaty. Tecumseh acknowledged to Harrison that he had threatened to kill the chiefs who signed the treaty if they carried out its terms, and that his confederation was rapidly growing.[20] Harrison responded to Tecumseh that the Miami were the owners of the land and could sell it if they so choose. He also rejected Tecumseh's claim that all the Indians formed one nation, and each nation could have separate relations with the United States. As proof Harrison told Tecumseh that the Great Spirit would have made all the tribes to speak one language if they were to be one nation.[21]

Tecumseh launched an "impassioned rebuttal", but Harrison was unable to understand his language. A Shawnee who was friendly to Harrison cocked his pistol from the side lines to alert Harrison that Tecumseh's speech was leading to trouble. Finally an army lieutenant who could speak Tecumseh's language warned Harrison that he was encouraging the warriors with him to kill Harrison. Many of the warriors began to pull their weapons and Harrison pulled his sword. The entire town's population was only 1,000 and Tecumseh's men could have easily massacred the town, but once the few officers pulled their guns to defend Harrison the warriors backed down.[21] Chief Winnemac, who was friendly to Harrison, countered Tecumseh's arguments to the warriors and instructed them that because they had come in peace, they should return in peace and fight another day. Before leaving, Tecumseh informed Harrison that unless the treaty was nullified, he would seek an alliance with the British.[22]

A comet appeared in March 1811. The Shawnee leader Tecumseh, whose name (Tekoomsē) meant "Shooting Star" or "Panther Across The Sky",[23] traveled throughout the Southeast where he told the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee, and many others that the comet signaled his coming. McKenney reported that the Tecumseh would prove that the Great Spirit had sent him by giving the them a sign. Shortly after Tecumseh left the Southeast, the sign arrived as promised in the form of an earthquake.

During the next year tensions began to rise quickly. Four settlers were murdered on the Missouri River and in another incident a boatload of supplies was seized by natives from a group of traders. Harrison summoned Tecumseh to Vincennes to explain the actions of his allies.[24] In August 1811, Tecumseh met with Harrison at Vincennes, assuring him that the Shawnee brothers meant to remain at peace with the United States. Tecumseh then traveled to the south on a mission to recruit allies among the "Five Civilized Tribes." Most of the southern nations rejected his appeals, but a faction among the Creeks, who came to be known as the Red Sticks, answered his call to arms, leading to the Creek War, which also became a part of the War of 1812[25] Tecumseh delivered many passionate speeches and convinced many to join his cause.

Brothers, we all belong to one family; we are all children of the Great Spirit; we walk in the same path; slake our thirst at the same spring; and now affairs of the greatest concern lead us to smoke the pipe around the same council fire! Brothers, we are friends; we must assist each other to bear our burdens. The blood of many of our fathers and brothers has run like water on the ground, to satisfy the avarice of the white men. We, ourselves, are threatened with a great evil; nothing will pacify them but the destruction of all the red men. Brothers, when the white men first set foot on our grounds, they were hungry; they had no place on which to spread their blankets, or to kindle their fires. They were feeble; they could do nothing for themselves. Our fathers commiserated their distress, and shared freely with them whatever the Great Spirit had given his red children. They gave them food when hungry, medicine when sick, spread skins for them to sleep on, and gave them grounds, that they might hunt and raise corn. Brothers, the white people are like poisonous serpents: when chilled, they are feeble and harmless; but invigorate them with warmth, and they sting their benefactors to death. The white people came among us feeble; and now that we have made them strong, they wish to kill us, or drive us back, as they would wolves and panthers. Brothers, the white men are not friends to the Indians: at first, they only asked for land sufficient for a wigwam; now, nothing will satisfy them but the whole of our hunting grounds, from the rising to the setting sun. Brothers, the white men want more than our hunting grounds; they wish to kill our old men, women, and little ones. Brothers, many winters ago there was no land; the sun did not rise and set; all was darkness. The Great Spirit made all things. He gave the white people a home beyond the great waters. He supplied these grounds with game, and gave them to his red children; and he gave them strength and courage to defend them. Brothers, my people wish for peace; the red men all wish for peace; but where the white people are, there is no peace for them, except it be on the bosom of our mother. Brothers, the white men despise and cheat the Indians; they abuse and insult them; they do not think the red men sufficiently good to live. The red men have borne many and great injuries; they ought to suffer them no longer. My people will not; they are determined on vengeance; they have taken up the tomahawk; they will make it fat with blood; they will drink the blood of the white people. Brothers, my people are brave and numerous; but the white people are too strong for them alone. I wish you to take up the tomahawk with them. If we all unite, we will cause the rivers to stain the great waters with their blood. Brothers, if you do not unite with us, they will first destroy us, and then you will fall an easy prey to them. They have destroyed many nations of red men, because they were not united, because they were not friends to each other. Brothers, the white people send runners amongst us; they wish to make us enemies, that they may sweep over and desolate our hunting grounds, like devastating winds, or rushing waters. Brothers, our Great Father [the King of England] over the great waters is angry with the white people, our enemies. He will send his brave warriors against them; he will send us rifles, and whatever else we want—he is our friend, and we are his children. Brothers, who are the white people that we should fear them? They cannot run fast, and are good marks to shoot at: they are only men; our fathers have killed many of them: we are not squaws, and we will stain the earth red with their blood. Brothers, the Great Spirit is angry with our enemies; he speaks in thunder, and the earth swallows up villages, and drinks up the Mississippi. The great waters will cover their lowlands; their corn cannot grow; and the Great Spirit will sweep those who escape to the hills from the earth with his terrible breath. Brothers, we must be united; we must smoke the same pipe; we must fight each other's battles; and, more than all, we must love the Great Spirit: he is for us; he will destroy our enemies, and make all his red children happy.[26]

On December 11, 1811, the New Madrid Earthquake shook the Muscogee lands and the Midwest. While the interpretation of this event varied from tribe to tribe, one consensus was universally accepted: the powerful earthquake had to have meant something. The earthquake and its aftershocks helped the Tecumseh resistance movement by convincing, not only the Muscogee, but other Native American tribes as well, that the Shawnee must be supported.

The Indians were filled with great terror ... the trees and wigwams shook exceedingly; the ice which skirted the margin of the Arkansas river was broken into pieces; and the most of the Indians thought that the Great Spirit, angry with the human race, was about to destroy the world.

— Roger L. Nichols, The American Indian

The Muscogee who joined Tecumseh's confederation were known as the Red Sticks. Stories of the origin of the Red Stick name varies, but one is that they were named for the Muscogee tradition of carrying a bundle of sticks that mark the days until an event occurs. Sticks painted red symbol war.[27]

[Governor William Harrison,] you have the liberty to return to your own country ... you wish to prevent the Indians from doing as we wish them, to unite and let them consider their lands as common property of the whole ... You never see an Indian endeavor to make the white people do this ... Sell a country! Why not sell the air, the great sea, as well as the earth? Did not the Great Spirit make them all for the use of his children? How can we have confidence in the white people?

— Tecumseh, 1810[28]

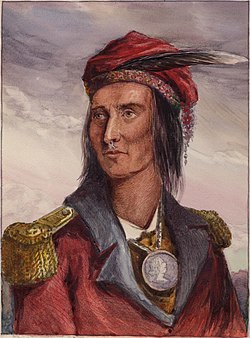

Portraits of Pushmataha (left) and Tecumseh. —Pushmataha, 1811 – Sharing Choctaw History.[29] —Tecumseh, 1811 – The Portable North American Indian Reader.[30] |

After Hull's surrender of Detroit, General William Henry Harrison was given command of the U.S. Army of the Northwest. He set out to retake the city, which was now defended by Colonel Henry Procter in conjunction with Tecumseh. A detachment of Harrison's army was defeated at Frenchtown along the River Raisin on January 22, 1813. Procter left the prisoners with an inadequate guard, who could not prevent some of his North American aboriginal allies from attacking and killing perhaps as many as sixty Americans, many of whom were Kentucky militiamen.[31] The incident became known as the "River Raisin Massacre." The defeat ended Harrison's campaign against Detroit, and the phrase "Remember the River Raisin!" became a rallying cry for the Americans.

In May 1813, Procter and Tecumseh set siege to Fort Meigs in northern Ohio. American reinforcements arriving during the siege were defeated by the natives, but the fort held out. The Indians eventually began to disperse, forcing Procter and Tecumseh to return to Canada. A second offensive against Fort Meigs also failed in July. In an attempt to improve Indian morale, Procter and Tecumseh attempted to storm Fort Stephenson, a small American post on the Sandusky River, only to be repulsed with serious losses, marking the end of the Ohio campaign.

On Lake Erie, American commander Captain Oliver Hazard Perry fought the Battle of Lake Erie on September 10, 1813. His decisive victory ensured American control of the lake, improved American morale after a series of defeats, and compelled the British to fall back from Detroit. This paved the way for General Harrison to launch another invasion of Upper Canada, which culminated in the U.S. victory at the Battle of the Thames on October 5, 1813, in which Tecumseh was killed. Tecumseh's death effectively ended the North American indigenous alliance with the British in the Detroit region. American control of Lake Erie meant the British could no longer provide essential military supplies to their aboriginal allies, who therefore dropped out of the war. The Americans controlled the area during the conflict.

Aftermath

The Shawnee in Missouri became known as the "Absentee Shawnee". Several hundred members of this tribe left the United States together with some Delaware to settle in the eastern part of Spanish Texas. Although closely allied with the Cherokee led by The Bowl, their chief John Linney remained neutral during the 1839 Cherokee War. In appreciation, Texan president Mirabeau Lamar fully compensated the Shawnee for their improvements and crops when funding their removal north to Arkansaw Territory.[32] The Shawnee settled close to present-day Shawnee, Oklahoma. They were joined by Shawnee from Kansas who shared their traditionalist views and beliefs.

In 1817, the Ohio Shawnee signed the Treaty of Fort Meigs, ceding their remaining lands in exchange for three reservations in Wapaughkonetta, Hog Creek (near Lima) and Lewistown, Ohio. They shared these lands with the Seneca.

Missouri joined the Union in 1821. After the Treaty of St. Louis in 1825, the 1,400 Missouri Shawnee were forcibly relocated from Cape Girardeau to southeastern Kansas, close to the Neosho River.

During 1833, only Black Bob's band of Shawnee resisted removal. They settled in northeastern Kansas near Olathe and along the Kansas (Kaw) River in Monticello near Gum Springs. The Shawnee Methodist Mission was built nearby to minister to the tribe. About 200 of the Ohio Shawnee followed the prophet Tenskwatawa and joined their Kansas brothers and sisters in 1826.

The main body followed Black Hoof, who fought every effort to force the Shawnee to give up their Ohio homeland. In 1831, the Lewistown group of Seneca–Shawnee left for the Indian territory (present-day Oklahoma). After the death of Black Hoof, the remaining 400 Ohio Shawnee in Wapaughkonetta and Hog Creek surrendered their land and moved to the Shawnee Reserve in Kansas.

In the 1853 Indian Appropriations Bill, Congress appropriated $64,366 for treaty obligations to the Shawnee such as annuities, education, and other services. An additional $2,000 was appropriated for the Seneca and the Shawnee together.[33]

During the American Civil War, Black Bob's band fled from Kansas and joined the "Absentee Shawnee" in Oklahoma to escape the war. After the Civil War, the Shawnee in Kansas were expelled and forced to move to northeastern Oklahoma. The Shawnee members of the former Lewistown group became known as the "Eastern Shawnee".

The former Kansas Shawnee became known as the "Loyal Shawnee" (some say this is because of their allegiance with the Union during the war; others say this is because they were the last group to leave their Ohio homelands). The latter group was regarded as part of the Cherokee Nation by the United States because they were also known as the "Cherokee Shawnee". In 2000 the "Loyal" or "Cherokee" Shawnee finally received federal recognition independent of the Cherokee Nation. They are now known as the "Shawnee Tribe". Today, most of the members of the Shawnee nation still reside in Oklahoma.

Groups

Before contact with Europeans, the Shawnee tribe consisted of a loose confederacy of five divisions which shared a common language and culture. The division names have been spelled in a variety of ways.[34] The divisions are:

- Chillicothe (Principal Place), Chalahgawtha, Chalaka, Chalakatha;

- Hathawekela, Thawikila;

- Kispoko, Kispokotha, Kishpoko, Kishpokotha;

- Mekoche, Mequachake, Machachee, Maguck, Mackachack, etc.;

- Pekowi, Pekuwe, Piqua, Pekowitha.

In addition to the five divisions, the Shawnee can be divided into six clans or subdivisons.[35] Each name group is common among each for the five divisions and each Shawnee belongs to a group.[35] The six group names are:

- Pellewomhsoomi (Turkey name group)—represents bird life,

- Kkahkileewomhsoomi (Turtle name group)—represents aquatic life,

- Petekoθiteewomhsoomi (Rounded-feet name group)—represents carnivorous animals like the dog, wolf, or whose paws are ball-shaped or "rounded,"

- Mseewiwomhsoomi (Horse name group)—represents herbivorous animals as the horse and deer,

- θepatiiwomhsoomi (Raccoon name group)—represents animals having paws which can rip and tear like those of a raccoon and bear.

- Petakineeθiiwomhsoomi (Rabbit name group)—represents a gentle and peaceful nature.[35]

Membership in a division was inherited from the father, unlike the matrilineal descent often associated with other tribes. Each division had a primary village where the chief of the division lived. This village was usually named after the division. By tradition, each Shawnee division had certain roles it performed on behalf of the entire tribe. By the time they were recorded in writing by European-Americans, these strong social traditions were fading. They remain poorly understood. Because of the scattering of the Shawnee people from the 17th century through the 19th century, the roles of the divisions changed.

Today there are three federally recognized tribes in the United States, all of which are located in Oklahoma:

- The Absentee-Shawnee Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma, consisting mainly of Hathawekela, Kispokotha, and Pekuwe;

- The Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, mostly of the Mekoche division; and

- The Shawnee Tribe, formerly an official part of the Cherokee Nation, mostly of the Chaalakatha and Mekoche divisions.

As of 2008, there were 7584 enrolled Shawnee, with most living in Oklahoma.[36]

Shawnee in Ohio and other states

At least four bands of Shawnee reside in Ohio:

- The United Remnant Band of the Shawnee Nation[37][38]

- the Blue Creek Band,

- the East of the River Shawnee,

- the Piqua Shawnee Tribe

- Ridgetop Shawnee - Kentucky - In 2009 and 2010, the State House of the Kentucky General Assembly recognized the Ridgetop Shawnee Tribe of Indians by passing, unopposed, House Joint Resolutions 15 or HJR-15 in 2009 and HJR-16 in 2010. [39] [40].

These bands are not federally recognized, though some legal scholars dispute the formality of this recognition.[41]

The Piqua Shawnee Tribe are officially recognized in Alabama by the Alabama Indian Affairs Commission in accordance to the Davis-Strong Act,[42] and in Ohio by Ohio Senate Resolution 188, adopted February 26, 1991 and by the Ohio House of Representatives 119th General Assembly Resolution No. 83, adopted April 3, 1991 as presented to the Bureau of Indian Affairs Washington, D.C., and in Kentucky by Governor's Proclamation dated August 13, 1991.[43]

Flags of the Shawnee

-

Flag of the Absentee-Shawnee Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma

-

Flag of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma

-

Flag of the Shawnee Tribe

-

Flag of the Shawnee Nation United Remnant Band of Ohio

Coins of the Shawnee

-

First coin issue of 2002—one dollar

-

Tecumseh commemorative dollar

Famous Shawnee

- Cornstalk (1720–1777), led the Shawnee in Dunmore's War,

- Blue Jacket (1743–1810), also known as Weyapiersenwah, was an important predecessor to Tecumseh and a leader in the Northwest Indian War.

- Black Hoof (1740–1831), also known as Catecahassa, was a respected Shawnee chief who believed the Shawnee had to adapt to European-American culture to survive.

- Chiksika (1760–1792), Kispoko war chief and older brother of Tecumseh

- Tecumseh (1768–1813), Shawnee leader; with his brother Tenskwatawa attempted to unite the Eastern tribes against the expansion of European-American settlement.

- Tenskwatawa (1775–1836), Shawnee prophet and younger brother of Tecumseh

- Black Bob, 19th century leader and warrior

- Sat-Okh (1920–2003), Polish-Shawnee Canadian, fought in WWII, novelist

- Nas'Naga (born 1941), Shawnee U.S. novelist and poet.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Oklahoma Indian Affairs Commission. Oklahoma Indian Nations Pocket Pictorial. 2008.

- ^ Shawano was an archaic name for the tribes bearing this generic name Shaawanwa lenaki. Reference: Shawnee Traditions

- ^ O'Donnell, James H. Ohio's First Peoples, p. 31. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8214-1525-5 (paperback), ISBN 0-8214-1524-7 (hardcover)

- ^ Howard, James H. Shawnee!: The Ceremonialism of a Native Indian Tribe and its Cultural Background, p. 1. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1981. ISBN 0-8214-0417-2; ISBN 0-8214-0614-0 (pbk.)

- ^ Schutz, Noel W., Jr.: The Study of Shawnee Myth in an Ethnographic and Ethnohistorical Perspective, Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Indiana University, 1975.

- ^ See Squier p. 1

- ^ Peregrine, Peter N. (2001). Encyclopedia of Prehistory. Springer. p. - 175. ISBN 0306462605.

- ^ Drooker 1997a:203

- ^ Peregrine & Ember 2002:184

- ^ "Tennessee Encyclopedia of Culture and History". Retrieved 2008-09-11.

{{cite web}}:|article=ignored (help) - ^ Charles Augustus Hanna, 1911 The Wilderness Trail, esp. chap. IV, "The Shawnees", pp. 119–160.

- ^ Carrie Hunter Willis and Etta Belle Walker, Legends of the Skyline Drive and the Great Valley of Virginia, 1937, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Edward Bland, The Discoverie of New Brittaine,

- ^ Gallay, Alan. The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670–1717, p. 55. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-300-10193-7

- ^ Legends of the Skyline Drive and the Great Valley of Virginia, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Joseph Doddridge, 1850, A History of the Valley of Virginia, p. 44

- ^ Gevinson, Alan. "Which Native American Tribes Allied Themselves with the French?" Teachinghistory.org, accessed 23 September 2011.

- ^ a b Owens, p. 201–203

- ^ a b c d Owens, p. 212

- ^ a b Langguth, p.164

- ^ a b Langguth, p. 165

- ^ Langguth, p. 166

- ^ George Blanchard, the Governor of the Absentee Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, so describes the meaning of the name in the PBS documentary We Shall Remain: Tecumseh's Vision: "Well, I've always heard 'Teh-cum-theh'—'Teh-cum-theh'—means, in our culture and our belief, at nights when we see a falling star, it means that this panther is jumping from one mountain to another. And as kids, we saw these falling stars, we'd kind of hesitate about being out in the dark, because we thought there were actually panthers out there walking around. So that's what his name meant: Teh-cum-theh."

- ^ Langguthh, p. 166

- ^ Langguth, p. 167

- ^ Hunter, John Dunn (1824). Memoirs of a captivity among the Indians of North America, from childhood to the age of nineteen: with anecdotes descriptive of their manners and customs. Longman, Hurst, Orme, Brown, and Green. London. pp. 45–48. (accessible online in books.google)

- ^ "The Creeks." War of 1812" People and Stories. (retrieved 5 Dec 2009)

- ^ Turner III, Frederick (1810). "Poetry and Oratory". The Portable North American Indian Reader. Penguin Book. pp. 245–246. ISBN 0-14-015077-3.

- ^ Jones, Charile (1987). "Sharing Choctaw History". University of Minnesota. Retrieved 2008-02-05.

{{cite web}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Turner III, Frederick (1978) [1973]. "Poetry and Oratory". The Portable North American Indian Reader. Penguin Book. pp. 246–247. ISBN 0-14-015077-3.

- ^ "Kentucky: National Guard History eMuseum - War of 1812". Kynghistory.ky.gov. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- ^ Lipscomb, Carol A.: "Shawnee Indians" from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ "Indian Appropriation". The New York Times. March 15, 1853. p. 3.

- ^ Sugde, John (1997). "The Panther and the Turtle". Tecumseh: A Life. Henry Holt and Company, LLC. p. 13. ISBN 0805061215.

- ^ a b c

"Shawnee Name Groups". American Anthropologist: 617–635. 1935. doi:10.1525/aa.1935.37.4.02a00070.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Oklahoma Indian Commission. Oklahoma Indian Nations Pocket Pictorial. 2008

- ^ "American Indians in Ohio", Ohio Memory: An Online Scrapbook of Ohio History, The Shawnee Nation United Remnant Band, The Ohio Historical Society, retrieved September 30, 2007

- ^ "Joint Resolution to recognize the Shawnee Nation United Remnant Band" as adopted by the [Ohio] Senate, 113th General Assembly, Regular Session, Am. Sub. H.J.R. No. 8, 1979–1980

- ^ "Kentucky General Assembly 2010 Regular Session HJR-16". kentucky.gov, updated 9-2-2010.

- ^ "Kentucky General Assembly 2009 Regular Session HJR-15". kentucky.gov, updated 5-2-2009.

- ^ Watson, Blake A. "Indian Gambling in Ohio:What are the Odds?" (PDF). Capital University Law Review 237 (2003) (excerpts). Retrieved 2007-09-30.

Ohio in any event does not officially recognize Indian tribes.

Watson cites legal opinions that the resolution by the Ohio Legislature recognizing the United Remnant Band of the Shawnee Nation was ceremonial and did not grant legal status as a tribe. Confirmation of the Remnant Bands recognition is referred to and presented to the Bureau of Indian Affairs and The President of the United States in 1981. - ^ Alabama Indian Affairs Commission

- ^ Koenig, Alexa. "Federalism and the State Recognition of Native American Tribes: A Survey of State-Recognized Tribes and State Recognition Processes Across the United States". Santa Clara Law Review Volume 48 (forthcoming). pp. Section 12. Ohio. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

Ohio recognizes one state tribe, the United Remnant Band. . . . Ohio does not have a detailed scheme for regulating tribal-state relations.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

References

- Callender, Charles. "Shawnee", in Northeast: Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 15, ed. Bruce Trigger. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1978. ISBN 0-16-072300-0

- Clifton, James A. Star Woman and Other Shawnee Tales. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1984. ISBN 0-8191-3712-X; ISBN 0-8191-3713-8 (pbk.)

- Edmunds, R. David. The Shawnee Prophet. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1983. ISBN 0-8032-1850-8.

- Edmunds, R. David. Tecumseh and the Quest for Indian Leadership. Originally published 1984. 2nd edition, New York: Pearson Longman, 2006. ISBN 0-321-04371-5

- Edmunds, R. David. "Forgotten Allies: The Loyal Shawnees and the War of 1812" in David Curtis Skaggs and Larry L. Nelson, eds., The Sixty Years' War for the Great Lakes, 1754–1814, pp. 337–51. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-87013-569-4.

- Howard, James H. Shawnee!: The Ceremonialism of a Native Indian Tribe and its Cultural Background. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1981. ISBN 0-8214-0417-2; ISBN 0-8214-0614-0 (pbk.)

- O'Donnell, James H. Ohio's First Peoples. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8214-1525-5 (paperback), ISBN 0-8214-1524-7 (hardcover).

- Sugden, John. Tecumseh: A Life. New York: Holt, 1997. ISBN 0-8050-4138-9 (hardcover); ISBN 0-8050-6121-5 (1999 paperback).

- Sugden, John. Blue Jacket: Warrior of the Shawnees. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8032-4288-3.

External links

select an article title from: Wikisource:1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- Absentee Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma

- Shawnee Nation United Remnant Band, Ohio

- Shawnee History

- Shawnee Indian Mission

- "Shawnee Indian Tribe", Access Genealogy

- Treaty of Fort Meigs, 1817, Central Michigan State University

- Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma

- The Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma

- BlueJacket

- Piqua Shawnee Tribe

- Shawnee tribe

- Algonquian ethnonyms

- Native American tribes in Indiana

- Native American tribes in Kentucky

- Native American tribes in Maryland

- Native American tribes in Ohio

- Native American tribes in Oklahoma

- Native American tribes in Pennsylvania

- Native American tribes in Virginia

- Native American tribes in West Virginia