Kronan (ship): Difference between revisions

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

{{main|Swedish empire}} |

{{main|Swedish empire}} |

||

[[File:Swedish Empire (1560-1815) en2.png|250px|alt=A map showing 17th century Sweden, including Finland, the Baltic States and holding in Pomerania, Wismar and Bremen-Verden|thumb|left|right|A map of Sweden's territorial gains and losses 1560–1815. Sweden was at its peak as a Baltic power in the years that ''Kronan'' served.]] |

[[File:Swedish Empire (1560-1815) en2.png|250px|alt=A map showing 17th century Sweden, including Finland, the Baltic States and holding in Pomerania, Wismar and Bremen-Verden|thumb|left|right|A map of Sweden's territorial gains and losses 1560–1815. Sweden was at its peak as a Baltic power in the years that ''Kronan'' served.]] |

||

In the 1660s, Sweden was at its height as a European [[great power]]. |

In the 1660s, Sweden was at its height as a European [[great power]]. It had just defeated Denmark, one of its main competitors for hegemony in the [[Baltic Sea|Baltic]], in the [[Torstenson War|Tortenson]] (1643–45) and [[Dano-Swedish War (1657–58)|Dano-Swedish Wars]] (1657–58). At the [[Second Treaty of Brömsebro (1645)|Treaties of Brömsebro]] (1645) and [[Treaty of Roskilde|Roskilde]] (1658), Denmark was forced to cede the islands of [[Gotland]] and [[Ösel]], all of its eastern territories on the [[Scandinavian Peninsula]], and parts of Norway. In a [[Dano-Swedish War (1658–1660)|third war]] (1658–60), King [[Charles X Gustav of Sweden|Charles X]] of Sweden attempted to finish off Denmark for good. In part, the move was bold royal ambition, but Sweden had also become a [[fiscal-military state|highly militarized society geared for almost constant warfare]].<ref>See [[Jan Glete]] (2002) ''War and the State in Early Modern Europe: Spain, the Dutch Republic and Sweden as Fiscal-Military States, 1500–1600.'' Routledge, London. ISBN 0-415-22645-7 for an in-depth study.</ref> Disbanding its armies meant paying outstanding wages, so there was an underlying incentive to keep hostilities alive and let soldiers live off enemy lands and plunder. However, the renewed attack on Denmark threatened the interests of the leading shipping nations of [[England]] and the [[Dutch Republic]], who were best served by keeping the Baltic politically divided. The Dutch intervened and allied themselves with Denmark, dooming Charles' attempt to subdue Denmark.<ref>Göran Rystad "Skånska kriget och kampen om hegemonin i Norden" in Rystad (2005), pp. 17–19</ref> |

||

Charles X died in February 1660 |

Charles X died in February 1660. Three months later, the [[Treaty of Copenhagen (1660)|Treaty of Copenhagen]] ended the war. Charles' son and successor, [[Charles XI]], was only five when his father died, so a [[regency council]]—led by the [[queen mother]] [[Hedvig Eleonora of Holstein-Gottorp|Hedvig Eleonora]]—assumed power until the young king came of age. Sweden had come close to almost complete control over trade in the Baltic, but the war revealed the need to prevent the formation of a powerful anti-Swedish alliance which included Denmark. There were some successes, with the [[Triple Alliance (1668)|Triple Alliance]] of England, Sweden, and the Dutch Republic, but that was the high point. By the spring of 1672, Sweden had improved its relations with France enough to form an alliance. That same year, King [[Louis XIV]] attacked the [[Dutch Republic]] and in 1674, Sweden was pressured into joining the war by attacking the Republic's northern German allies. France promised to pay Sweden desperately needed war subsidies only on the condition that it moved in force on [[Brandenburg-Prussia|Brandenburg]]. A Swedish army of around 22,000 men under [[Carl Gustaf Wrangel]] advanced into Brandenburg in December 1674 and suffered a minor tactical defeat at the [[Battle of Fehrbellin]] in June 1675. Though not militarily significant, the defeat tarnished the reputation of near-invincibility that Swedish arms had enjoyed since the [[Thirty Years' War]]. This emboldened Sweden's enemies and by September 1675, Denmark, the Dutch Republic, and the [[Holy Roman Empire]] were all at war against Sweden and France.<ref>Göran Rystad "Skånska kriget och kampen om hegemonin i Norden" in Rystad (2005), pp. 20–21</ref> |

||

===State of the fleet=== |

===State of the fleet=== |

||

The [[ |

The [[First Anglo-Dutch War]] (1652–54) saw the development of the [[line of battle]], a tactic where ships formed a continuous line to shoot [[broadside]]s at an enemy. Previously, [[naval tactics]] were based on individual ships or small units within the frame of what has later been called the ''melee tactic''. Decisive action in sea battles had been achieved through boarding, but after the middle of the 17th century, tactical theory stressed disabling or sinking an opponent through superior firepower shot at a distance. This entailed major changes in doctrine, shipbuilding, and professionalism in European navies from the 1650s and onwards.<ref>Glete (1993), s. 173–178.</ref> |

||

The line of battle favored very large ships that were steady |

The line of battle favored very large ships that were steady sailors and that could hold the line in the face of heavy fire. This new style of warfare was marked by a successively stricter organization.{{clarify|are we still talking about the line of battle? I'd combine the paragraphs if you are}} The new tactics were also dependent on an increased disciplining of society and the demands of powerful centralized governments that could maintain large, permanent and loyal fleets led by a corps of professional officers. Battle formations became standardized, worked out from mathematically calculated ideal models. The increased power of the state at the expense of individual landowners led to increasingly larger armies and navies, and in the late 1660s, Sweden embarked on an expansive shipbuilding program.<ref>Glete (1993), p. 176.</ref> |

||

[[File:Suecia 1-013 ; Stockholm från öster-right side detail.jpg|thumb|center|600px|Detail of engraving of [[Stockholm]] from ''[[Suecia antiqua et hodierna]]'' by [[Erik Dahlberg]] and [[Willem Swidde]], printed in 1693. The view shows the Swedish as a bustling port, and in the foreground the peak of [[Kastellholmen]] next to the royal shipyards on [[Skeppsholmen]].]] |

[[File:Suecia 1-013 ; Stockholm från öster-right side detail.jpg|thumb|center|600px|Detail of engraving of [[Stockholm]] from ''[[Suecia antiqua et hodierna]]'' by [[Erik Dahlberg]] and [[Willem Swidde]], printed in 1693. The view shows the Swedish as a bustling port, and in the foreground the peak of [[Kastellholmen]] next to the royal shipyards on [[Skeppsholmen]].]] |

||

By 1675, the Swedish fleet was numerically superior to its Danish counterpart (18 ships of the line against 16, 21 frigates against 11), but it was still older and of poorer quality than the Danish fleet, which had replaced a larger proportion of its vessels. The Swedish side had problems with its routine maintenance and both rigging and sails were generally in poor condition. Swedish crews also lacked the same level of professionalism as the Danish and Norwegian sailors, who commonly had valuable experience from service in the Dutch merchant navy. Compounding the situation further, the Swedish Navy lacked a core of professional naval officers, while the Danish had seasoned veterans like [[Cort Adeler]] and [[Nils Juel]]. The Danish fleet was soon reinforced with Dutch units under [[Philip van Almonde]] and [[Cornelis Tromp]], the latter an experienced officer who had served under [[Michiel de Ruyter]].<ref>Finn Askgaard, "Kampen till sjöss" in Rystad (2005), p. 172</ref> |

|||

== Design == |

== Design == |

||

Revision as of 01:46, 24 April 2014

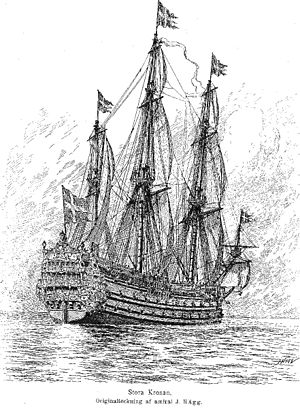

Reconstruction by Jacob Hägg, 1909

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Kronan |

| Builder | Francis Sheldon, Stockholm |

| Laid down | October 1665 |

| Launched | 31 July 1668 |

| Commissioned | 1672 |

| Fate | Sunk at the Battle of Öland, 1 June 1676 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Ship of the line |

| Displacement | 2,300 tonnes (approximate) |

| Length | 53 m (174 ft) |

| Beam | 12.9 m (42 ft) |

| Height | 66 m (217 ft, keel to mast) |

| Draft | 6.2-6.8 m (20-22 ft) |

| Sail plan | Three masts |

| Troops | 300 soldiers |

| Complement | 500 sailors |

| Armament | list error: <br /> list (help) Planned for 126 guns from 6 to 36 pound Actual armament around 105 guns |

Kronan, also called Stora Kronan,[1] was a Swedish warship that served as the flagship of the Swedish navy in the Baltic Sea in the 1670s. When built, she was one of the largest seagoing vessels in the world. The construction of Kronan lasted from 1668 to 1672, delayed by difficulties with financing and conflicts between the shipwright Francis Sheldon and the Swedish admiralty. After just four years of service the ship foundered in rough weather at the Battle of Öland on 1 June 1676. While making a sharp turn under too much sail she capsized, and the gunpowder magazine was accidentally ignited and blew off most of the bow structure. Kronan sank quickly, taking about 800 men and over 100 guns with her, along with valuable personal items, military equipment, weapons and large quantities of silver and gold coins.

The loss of Kronan was a hard blow for Sweden during the Scanian War (1675–79). Besides being the largest and most heavily armed ship in the Swedish navy, she had also been an important prestige symbol for the monarchy of the young Charles XI. Along with Kronan, the navy lost a sizeable proportion of its best manpower, acting supreme commander Lorentz Creutz, numerous high-ranking fleet officers and the chief of the navy medical staff. A commission was set up to investigate whether any individuals could be held responsible for the Swedish fiasco at the Battle of Öland and other major defeats during the war. Although no one was officially held accountable, Creutz has been blamed by many historians for the sinking of Kronan because of his general naval and command inexperience. Recent research has provided a more nuanced picture, and points to Sweden's general lack of a well-developed naval organization and officer corps at the time.

Most of the guns that sank with Kronan were salvaged in the 1680s, but eventually the wreck fell into obscurity. Its exact position was rediscovered in 1980 by the amateur researcher Anders Franzén, who had also located the 17th-century warship Vasa in the 1950s. Yearly diving operations have since surveyed and excavated the wreck site and salvaged artifacts, and Kronan has become the most widely publicized shipwreck in the Baltic after Vasa. More than 30,000 artifacts have been recovered, and many have been conserved and put on permanent display for the general public at the Kalmar County Museum in Kalmar. The museum is today responsible for the maritime archaeological operations and the permanent exhibitions on Kronan.

Historical background

In the 1660s, Sweden was at its height as a European great power. It had just defeated Denmark, one of its main competitors for hegemony in the Baltic, in the Tortenson (1643–45) and Dano-Swedish Wars (1657–58). At the Treaties of Brömsebro (1645) and Roskilde (1658), Denmark was forced to cede the islands of Gotland and Ösel, all of its eastern territories on the Scandinavian Peninsula, and parts of Norway. In a third war (1658–60), King Charles X of Sweden attempted to finish off Denmark for good. In part, the move was bold royal ambition, but Sweden had also become a highly militarized society geared for almost constant warfare.[2] Disbanding its armies meant paying outstanding wages, so there was an underlying incentive to keep hostilities alive and let soldiers live off enemy lands and plunder. However, the renewed attack on Denmark threatened the interests of the leading shipping nations of England and the Dutch Republic, who were best served by keeping the Baltic politically divided. The Dutch intervened and allied themselves with Denmark, dooming Charles' attempt to subdue Denmark.[3]

Charles X died in February 1660. Three months later, the Treaty of Copenhagen ended the war. Charles' son and successor, Charles XI, was only five when his father died, so a regency council—led by the queen mother Hedvig Eleonora—assumed power until the young king came of age. Sweden had come close to almost complete control over trade in the Baltic, but the war revealed the need to prevent the formation of a powerful anti-Swedish alliance which included Denmark. There were some successes, with the Triple Alliance of England, Sweden, and the Dutch Republic, but that was the high point. By the spring of 1672, Sweden had improved its relations with France enough to form an alliance. That same year, King Louis XIV attacked the Dutch Republic and in 1674, Sweden was pressured into joining the war by attacking the Republic's northern German allies. France promised to pay Sweden desperately needed war subsidies only on the condition that it moved in force on Brandenburg. A Swedish army of around 22,000 men under Carl Gustaf Wrangel advanced into Brandenburg in December 1674 and suffered a minor tactical defeat at the Battle of Fehrbellin in June 1675. Though not militarily significant, the defeat tarnished the reputation of near-invincibility that Swedish arms had enjoyed since the Thirty Years' War. This emboldened Sweden's enemies and by September 1675, Denmark, the Dutch Republic, and the Holy Roman Empire were all at war against Sweden and France.[4]

State of the fleet

The First Anglo-Dutch War (1652–54) saw the development of the line of battle, a tactic where ships formed a continuous line to shoot broadsides at an enemy. Previously, naval tactics were based on individual ships or small units within the frame of what has later been called the melee tactic. Decisive action in sea battles had been achieved through boarding, but after the middle of the 17th century, tactical theory stressed disabling or sinking an opponent through superior firepower shot at a distance. This entailed major changes in doctrine, shipbuilding, and professionalism in European navies from the 1650s and onwards.[5]

The line of battle favored very large ships that were steady sailors and that could hold the line in the face of heavy fire. This new style of warfare was marked by a successively stricter organization.[clarification needed] The new tactics were also dependent on an increased disciplining of society and the demands of powerful centralized governments that could maintain large, permanent and loyal fleets led by a corps of professional officers. Battle formations became standardized, worked out from mathematically calculated ideal models. The increased power of the state at the expense of individual landowners led to increasingly larger armies and navies, and in the late 1660s, Sweden embarked on an expansive shipbuilding program.[6]

By 1675, the Swedish fleet was numerically superior to its Danish counterpart (18 ships of the line against 16, 21 frigates against 11), but it was still older and of poorer quality than the Danish fleet, which had replaced a larger proportion of its vessels. The Swedish side had problems with its routine maintenance and both rigging and sails were generally in poor condition. Swedish crews also lacked the same level of professionalism as the Danish and Norwegian sailors, who commonly had valuable experience from service in the Dutch merchant navy. Compounding the situation further, the Swedish Navy lacked a core of professional naval officers, while the Danish had seasoned veterans like Cort Adeler and Nils Juel. The Danish fleet was soon reinforced with Dutch units under Philip van Almonde and Cornelis Tromp, the latter an experienced officer who had served under Michiel de Ruyter.[7]

Design

Kronan was one of the most heavily armed warships of her time, a three-decker with 105 guns. She had three gundecks with guns from bow to stern. Altogether there were seven separate levels divided by six decks. Furthest down in the ship, above the keel, was the hold and immediately above it, but still below the waterline, lay the orlop; both were used primarily for storage. Above the orlop were the three gundecks, two of which were covered, while about half of the topmost gundeck was open to the elements in the middle, or waist, of the ship. The bow had one deck, making up the forecastle, and the stern had two decks, including a poop deck.[8]

During the first half of the 17th century, Swedish warships were built according to the Dutch manner, with a flat, rectangular bottom with a small draft. This was a shipbuilding style adapted for the shallow coastal waters of the Netherlands, and allowed for quick construction and tended towards smaller ships. The drawback was that the vessels had relatively light, less sturdy structures that were somewhat unstable in rough seas, aspects generally unsuitable for warships. When Kronan was built, the English manner of building had prevailed, giving hulls a more rounded bottom and greater draft, as well as a sturdier frame and increased stability. The underwater part of the stern was also more streamlined below the waterline, which lessened resistance.[9] The measurements for Kronan were recorded in contemporary navy lists. Its length from stem post to stern post (much shorter than the actual length if bowsprit or beakhead were included) was 53 m (174 ft) and the width (the widest measurement between the frames without planking) was 12.9 m (42 ft). The draft varied depending on how heavily she was laden, but with full stores, ammunition and armaments it would have been about 6.2-6.8 m (20-22 ft).[10] The height of the ship from keel to the highest mast is not known as it was never recorded, but Kalmar County Museum has estimated it to have been at least 66 m (217 ft).[11]

Kronan's displacement, the ship's weight calculated by how much water it displaced while floating, is not known precisely since there are no exact records of the dimensions. By using contemporary documents describing the approximate measurements, it has been estimated to around 2,300 tonnes. In relation to the number, and sheer weight, of guns, Kronan was heavily over-gunned. Until after about 1650 European shipwrights had not begun building three-deckers on a large scale, and the designs were by the 1660s still quite experimental. Both English and French three-deckers were known to be unstable since they were built high, narrow and armed with too many guns. The distance between the lowest gunports and the waterline was also quite small. In rough seas these ships were often forced to close the lowest row of gunports, and were thereby deprived of the use of their heaviest guns, their most effective weapons. In effect they were then rendered into over-prices two-deckers. In the 18th century, ships with the same weight of guns as Kronan were built much more heavily, usually from 3,000 up to 5,000 tonnes, which made them much more stable. When Kronan was built, she was ranked as the third or fourth largest ship in the world, but as the trend moved towards ever greater ships, she was surpassed by several other large warships. At the time Kronan sank, she was down to seventh place, a position shared with many other ships.[12]

Armament

According to the official armament plan Kronan was to be equipped with 124–126 guns; 34–36 guns on each of the gundecks and an additional 18 in the forecastle and sterncastle decks. Guns were classed by the weight of the cannonballs they fired, varying between 3 and 36 pounds (1.3–15.3 kg). The guns themselves weighed from a few hundred kg up to four tonnes with the heaviest pieces placed in the middle of the lower-most gundeck with successively lighter ones on the decks above. Kronan's most lethal weapons were the 30- and 36-pounders on the lowest gundeck which had a range and firepower that outclassed the armament of just about any other warship. Much of the armament under 18 pounds was primarily designed to inflict damage on the enemy's crew and rigging rather than the hull.[13]

According to modern research, the number of guns was considerably less than the official armament plan. At the time, armament plans regularly overstated the actual number of guns available. In reality, they were ideal estimations that seldom reflected actual conditions, either because of a lack of ordnance or because they were impractical when tested. Heavy 30- and 36-pounder guns were particularly difficult to find in sufficient numbers and lighter guns were frequently used instead. Going by the number of guns that were salvaged from Kronan in the 1680s (see "History as a shipwreck") and during the excavations in the 1980s the total comes to around 105. This matches calculations of the number of gunports based on the remains of the wreck and how many guns that could practically be housed on the gun decks.[13]

There were several types of ammunition available for different uses: round shot (cannonballs) against ship hulls, chain shot against masts and rigging, and canister shot (wooden cylinders filled with metal balls or fragments), which had a devastating effect on tightly packed groups of men. For boarding actions Kronan was equipped with 130 muskets and 80 matchlock or flintlock pistols. For close combat there were also 250 pikes, 200 boarding axes and 180 swords.[14] During the excavations large-caliber hakebössor, firearms were found, similar to blunderbusses. They were equipped with a small catch underneath which allowed them to be hooked over a railing and thereby absorb the recoil of the massive charges. One hakebössa was still loaded with a small canister containing 20 lead balls that would have been used to clear enemy decks before boarding.[15]

Ornamentation

Expensive ornamentation was an important part of a ship's appearance in the 1660s, even though it had been considerably simplified since the early 17th century. It was believed to be important to enhance the authority of absolute monarchs and to portray the ship as a projection of his martial prowess and power. There are no contemporary illustrations of what the ornamentation of Kronan looked like, but according to common practice, it was most lavish on the transom, the flat surface facing aft. There are two images of Kronan shown from stern, both by Danish artists. Both were commissioned many years after the sinking in order to commemorate the crushing Danish victory. Claus Møinichen's painting at Fredriksborg Palace from 1686 shows a transom dominated by two lions rampant holding up a huge royal crown. The background is blue with sculptures and ornaments in gold. Swedish art historian Hans Soop, who has previously studied the sculptures of Vasa, built 1626–28, has suggested that Møinichen may have intentionally exaggerated the size of the ship in order to enhance the Danish victory. A tapestry at Rosenborg Castle shows Kronan as a two-decker, and here the transom is dominated even more by the image of the crown.[16]

Archaeologists have not been able to recover enough of Kronan's sculptures for any detailed overview of the ornamentation. The mascarons (architectural facemasks) and putti (images of children) that have been salvaged so far, however, have shown considerable artistic quality according to Soop. One large sculpture of a warrior figure was found in 1987 and is an example of high-quality workmanship, and possibly a symbolic portrait of King Charles himself. Since nothing is known of the surrounding ornamentation and sculptures, however, the conclusion remains speculative.[17]

Construction

In the early 1660s, a building program was initiated to expand the fleet and replace old capital ships. A new flagship was also needed to replace the old Kronan from 1632.[18] The vast quantities of timber that were required for the new admiral's ship began to be felled already in the winter of 1664–65. Swedish historian Kurt Lundgren has estimated that 7–10 hectares (17–25 acres or 0.03–0.04 sq mi) of oak forest of hundred-year-old trees were required for the hull and several tall, stout pines for the masts and bowsprit.[19]

The construction of Kronan began in October 1665, and the hull was launched on 31 July 1668. The Englishman Francis Sheldon was the shipwright and frequently came in conflict with the Admiralty over the project. The navy administrators complained that he was delaying the project unduly and that he was spending too much time on his own private business ventures. The most aggravating was an extensive and lucrative export of mast timber to England. Sheldon in turn complained about constant delays on the navy's part and lack of funds.[20] When the ship was finally launched, the slipway turned out to be too small and the rear section of the keel broke off during the launching. The Admiralty demanded an explanation, but Sheldon's reply was that the damage was easily mended and that the problem was that the timber had been allowed to dry out too much.[21] The conflict between the Admiralty and Sheldon went on for several years and caused constant delays. The final sculptures were finished in 1669 but the rigging, tackling and arming was drawn out a further three years, to 1672. The first occasion that the ship actually sailed was during the celebrations of Charles XI's accession as monarch in December 1672.[22]

Crew

Being one of the largest ships of her time, Kronan had a large crew. When she sank there were 850 people on board, 500 sailors and 350 soldiers. Historians working with the excavation of the wrecksite have compared the ship with a middle-sized Swedish town of the late 17th century, describing it as a "miniature society". There were representatives of both the lower and upper classes on board, though only male. Women were allowed on navy vessels, but only within the limits of Stockholm archipelago; before reaching open water they had to disembark. As a community afloat Kronan mirrored the contemporary social standards of military and civilian life, two spheres that were not strictly separated in the 17th century. The entire crew dressed in civilian clothing and there were no common navy uniforms.[23] Clothing was differentiated according to social standing, with officers from the nobility dressed in elegant and expensive clothing while the crew dressed like ordinary laborers.[24] The only exceptions were the soldiers of the Västerbotten infantry regiment. By the 1670s it is believed that they had been equipped with the first "Carolingian"[25] uniforms in blue and white. The crew was sometimes assigned clothing or cloth with which to prepare "sailor garb" (båtmansklädning) which set them apart from the usual dress of the general populace. Officers maintained a large collection of fine clothing for use on board, but it is not known if they were actually used during everyday work. Quite likely they owned a set of clothes made from simpler, more durable and more comfortable fabrics which were more practical at sea.[26]

Recruitment was done by forced musters as a part of the earlier form of the so-called allotment system. Sailors and gunners were supplied by a båtsmanshåll (literally "sailor household"), small administrative units in coastal regions that were assigned the task of supplying the fleet with one adult male for navy service. The soldiers on board came from the army equivalent, knekthåll or rotehåll, ("soldier" or "ward household") from inland areas. Officers were for the most part from the nobility or from the upper middle class, paid through the allotment system or the income from estates designated for the purpose.[27] Higher-ranking officers most likely brought their personal servants on board. A valuable red jacket in bright red cloth that was worn by one of those who drowned on the ship could have belonged to one of these retinues.[28]

Military career

Expedition of 1675

After the Swedish loss at the battle of Fehrbellin in June 1675 the fleet was to support troop transports to reinforce Swedish Pomerania. The fleet had potential for success as it was equipped with several large, well-armed ships: Svärdet ("the sword") of 1,800 tonnes, Äpplet ("the orb") and Nyckeln ("the key"), both 1,400 tonnes, and the enormous Kronan ("the crown").[29] Altogether there were 28 large and medium warships and almost the same number of smaller vessels. The supply organization, however, was lacking, there were few experienced high-ranking officers and internal cooperation was poor; Danish contemporaries scornfully described the Swedish navy crews as mere "farmhands dipped in saltwater".[30]

With Kronan as its flagship, the fleet went to sea in October 1675 under Admiral of the Realm (riksamiral) Gustaf Otto Stenbock, but got no farther than Stora Karlsö off Gotland. The weather was unusually cold and stormy and the ships could not be heated. The crew were poorly clothed and soon many of them fell ill. Supplies eventually dwindled and after Kronan lost a sorely needed bow anchor, Stenbock decided to turn back to the Dalarö anchorage north of Stockholm after less than two weeks at sea. Nothing came of the reinforcements of the North German provinces. King Charles reacted with anger and held Stenbock personally responsible for the failed expedition, forcing him to pay over 100,000 dalers out of his own pocket.[31] King Charles later rehabilitated Stenbock by giving him an army appontingment in Norway, but in early 1676 he replaced him with Lorentz Creutz, a prominent Treasury official. Naval historian Jan Glete has explained this as a step that was "necessary in a time of crisis" due to Creutz's administrative skills and Treasury connections. However, Creutz had no experience as a naval commander, something that would later prove fateful.[32]

Failed winter expedition

As the situation for the Swedish army in Pomerania deteriorated during the winter, the fleet, once more with Kronan as flagship, was ordered out to sea once more in a desperate attempt to relieve the hard-pressed Swedish land forces. The winter of 1675–76 was unusually cold and large parts of the Baltic was iced in. When the fleet, now under the command of the seasoned sea officer Claes Uggla, reached Dalarö on 23 January, it was blocked by ice. The Privy Councilor Erik Lindschöld had been assigned by the King to assist with the winter expedition, and it was he who came up with the idea of literally cutting the fleet out of the ice to reach the open sea. Hundreds of local peasants were ordered out to open a narrow channel through the ice with saws and picks to the anchorage at Älvsnabben, over 20 km (12 mi) away. Upon reaching the naval station on February 14, three weeks later, it turned out that most of the sea outside the inner skerries was frozen as well. A storm hit the tightly packed ships and the ensuing movement of the ice crushed the hull of the supply vessel Leoparden and sank it. A Danish force had managed to reach the open waters farther off and observed the immobilized Swedish ships from a distance. When temperatures fell even further, the project was declared hopeless and even the energetic Lindschöld gave up the attempt.[33]

Spring of 1676

Early in March 1676, a Danish fleet of 20 ships under Admiral Niels Juel left Copenhagen. On April 29 it landed troops on Gotland, which soon surrendered. The Swedish fleet was ordered out on May 4, but experienced adverse winds and was delayed until 19 May. Juel had by then already left Visby, the principal port of Gotland with a garrison force. He headed for Bornholm to join with a small Danish-Dutch squadron to cruise between Scania and the island of Rügen to prevent any Swedish seaborne reinforcement from reaching Pomerania.[34] On May 25–26 the two fleets encountered one another in the battle of Bornholm. Even though the Swedes had a considerable advantage in ships, men and guns, they were unable to inflict any losses on the allied force, and lost a fireship and two minor vessels. The battle revealed the serious lack of coherence and organization within the Swedish ranks and soured relations between Creutz and his officers.[35]

After the unsuccessful action, the Swedish fleet anchored off Trelleborg where King Charles was waiting with new orders to recapture Gotland. The fleet was to avoid combat with the allies at least until they reached the northern tip of Öland, where they could fight in friendly waters. When the Swedish fleet left Trelleborg on May 30 they were soon intercepted by the allied fleet which then began a pursuit. By this time the allies had been reinforced by another small squadron and totalled 42 vessel, with 25 large or medium ships of the line. The reinforcements also brought with them a new commander, the Dutch Admiral General Cornelis Tromp, one of the most renowned naval tacticians of his time. The two fleets sailed north and on June 1 they passed the northern tip of Öland in a strong gale. The rough winds were hard on the Swedish ships and many lost masts and spars. The Swedish officers formed a battle line which was held together with great difficulty. They tried to get ahead of Tromp's ships to gain the weather gage by getting between the allies and the shore, and thereby gaining an advantageous tactical position. The Dutch ships of the allied fleet, however, managed to sail closer into the wind faster than the rest of the force and slipped between the Swedes and the coast, taking up the crucial weather gage. Later that morning the two fleets closed in on each other and were soon within firing range.[36]

Sinking

Around noon, some distance northeast of the village of Hulterstad, the Swedish fleet made what the military historian Ingvar Sjöblom has described as "a widely debated maneuver". Because of misunderstandings and poorly coordinated signalling, the Swedish fleet attempted to turn and engage the allied fleet before they had sailed past the northern end of Öland, which had been agreed upon before the battle. A sharp turn in rough weather was known to be perilous, especially if a ship was known to be somewhat unstable. Kronan turned to port (left), but with too much sail and heeled so far over that she began to flood through the open gunports. The crew was unable to correct the imbalance and she laid over completely with the masts parallel with the water. After a short while the gunpowder store in the forward part of the ship was for some reason ignited and exploded violently, ripping apart a large section of the starboard side forward of the mainmast. The remaining section rose with the stern pointing up in the air and the broken-off front part toward the bottom. She then rapidly sank with the port side down. When the wreck hit the seabed, the hull suffered a major fracture along its side which further damaged the structure.[37]

During the rapid sinking, a large proportion of the crew suffered severe trauma, as is shown by osteological analyses of the skeletal remains. Many of the remains had deep, unhealed lacerations on skulls, vertebrae, ribs and other limbs. Around 10% of all upper arm bones (humerus) and almost 20% of the thigh bones (femur) have signs of violence caused by sharp objects and in many cases there are repeated blows aimed at the same area. There has been no definite explanation for these wounds and none of the testimonies provide an explanation. There are no indications that any type of boarding action occurred before the sinking and forensic analysis has precluded that they were the result of the explosion. One theory is that discipline and social cohesion collapsed completely. Historian Ingvar Sjöblom has interpreted the finds as the aftermath of a "bloody scuffle" that broke out as the men fought among themselves as they tried to save themselves. Osteologist Ebba Düring has suggested that in the desperate struggle to get out, the men of the sinking ship resorted to "all the means at their disposal, both physical as well as psychological" to escape the catastrophic situation.[38] Medical historian Katarina Villner has offered a different explanation based on the assumption that the sinking was too fast to allow time for any violence between the men. Rather, the capsizing threw both men and heavy equipment and cannons around, causing the injuries evident in the skeletal remains.[39]

After the sinking of Kronan, the battle raged on for a few more hours, and was disastrous for the Swedes. The loss of the Admiral's flagship threw the Swedish forces into disorder, and soon Svärdet, next in line as fleet flagship, was surrounded by the allied admirals and set ablaze by a Dutch fireship after an extended artillery duel. Only 50 of the 650-strong crew escaped the gun battle and the inferno, and among the dead was the acting Admiral Claes Uggla. After losing two of its highest ranking commanders as well as its two largest ships, the Swedish fleet fled in disorder. Solen later ran aground while Järnvågen, Neptunus and three smaller vessels were captured. Äpplet was later wrecked after breaking her moorings off Dalarö and sank.[40]

Aftermath

According to the artillery officer Anders Gyllenspak, only 40 men, including himself, survived the sinking: Major Johan Klerk, 2 trumpeters, 14 sailors and 22 soldiers, which means that over 800 perished in the sinking. Among them were half a dozen navy and army officers as well as the chief physician of the Admiralty and the fleet apothecary. Altogether around 1,400 men died when Kronan and Svärdet were lost and in the days following the battle, hundreds of corpses were washed up on the east coat of Öland. According to the vicar of Långlöt parish, 183 men were taken from the beaches and buried at Hulterstad and Stenåsa graveyards.[41] Lorentz Creutz's body was identified and eventually shipped to his estate in Savolaks, Finland, where it was buried.[42] The losses were likely made even worse since Kronan was the flagship and would have been manned with the best sailors and gunners in the fleet.[43] When Kronan and Svärdet went down, they also took with them the navy's entire stock of heavy 30- and 36-pounder guns.[44] Altogether over 300 tonnes of bronze guns worth nearly 250,000 silver dalers went down with the ships, a sum that was actually slightly higher than the value of the ships themselves.[45]

Within a week, the news of the failure at Bornholm and the complete disaster at Öland reached King Charles, who immediately ordered that a commission be set up to investigate the fiasco. Charles wanted to know if Bär and other officers were guilty of cowardice or incompetence. On 13 June the King wrote that "some of our sea officers have shown such cowardly and careless behavior" that they "have placed the safety, welfare and defense of the kingdom at great peril" and that "such a great crime should be sternly punished".[46] The commission began its work on 7 June 1676 and was not finished until October 1677, but without passing any sentences. However, Admiral Johan Bär of Nyckeln and Lieutenant Admiral Christer Boije who ran aground with Äpplet, were never given a navy command again. One of the accused, Hans Clerck of Solen, fared much better, being promoted to full Admiral by the King even before the commission presented its findings.[40]

Causes of sinking

Inappropriate handling in rough weather was the most obvious cause for Kronan's sinking. Unlike Vasa, which sank during its maiden voyage almost fifty years earlier, Kronan's sailing characteristics were not inherently flawed and the ship had served for several years in rough seas. During the work of the commission, artillery officer Anders Gyllenspak even made direct comparisons to Vasa. He testified that Kronan's ballast had been lightened at Dalarö at the beginning of the campaign and that she had not replenished her supply of drink, though he did not blame this on Creutz. Because of these factors, the ship had a shallower draft and would have been somewhat less stable than with full stores.[47]

Why the Swedish fleet deviated from the original plan of engaging the allied force in home waters north of Öland has not been satisfactorily explained. According to Rosenberg and Gyllenspak on Kronan, Creutz made a turn because Uggla had signaled that he was going about. Rosenberg also believed that Bär on Nyckeln, admiral of the first squadron, was first to make a turn and that Uggla considered it necessary to follow him in order to keep the fleet together, even though it was an unplanned maneuver.[48] On the other hand, officers Anders Homman and Olof Norman, who both survived Svärdet, claimed that only Creutz as fleet commander could make such a decision and that Uggla was only following Kronan's lead.[49] Witnesses who testified before the commission claimed that conflict between the officers was the reason why necessary precautions were not taken before Kronan came about. Rosenberg also testified that Lieutenant Admiral Arvid Björnram and Major Klas Ankarfjäll had openly disagreed on how much sail should be set and how close to land the ship should sail.[50] According to Gyllenspak, senior fleet pilot Per Gabrielsson had voiced his concerns against turning in the rough weather, but no one had heeded his advice.[51]

Creutz has been blamed for the loss of his ship by several scholars and authors and been criticized as an incompetent sailor and officer who through lack of naval experience single-handedly brought about the sinking.[52] Historian Gunnar Grandin has suggested that the intent of the maneuver was to take advantage of the scattered allied fleet, but that many of the officers on Kronan opposed the idea; Creutz and Björnram urged that the ship turn quickly to gain a tactical advantage while Ankarfjäll and Gabrielsson were concerned about the immediate safety of the ship. Grandin has also suggested that Creutz may actually have suffered a mental breakdown after the failure at Bornholm and the open dispute with his officers, which eventually led to a rash and ultimately fatal decision.[53]

More recent views present the question of responsibility as more nuanced and complex: Creutz cannot be singled out as solely responsible for the disaster. Historians Ingvar Sjöblom and Lars Ericson Wolke have pointed out that Creutz's position as admiral was comparable to that of a chief minister. He would have primarily been an administrator without the need for intimate knowledge of practical details; turning a ship in rough weather would have been the responsibility of his subordinates. Sjöblom has stressed that the disagreement between Major Ankarfjäll and Lieutenant Admiral Björnram on how much sail was needed wasted precious time in a situation where quick decisions were crucial.[54] Creutz was also unique as a supreme commander of the navy since he had no experience of military matters whatsoever. The Swedish naval officer corps in the late 17th century lacked the prestige of army commanders, and consequentially seasoned officers and even admirals could be outranked by inexperienced civilians or army commanders with little or no naval background.[55] Maritime archaeologist Lars Einarsson has suggested that Creutz's "choleric and willful temperament" probably played a part, but that it all could just as well be blamed on an untrained and unexperienced crew and the open discord among the officers.[56] According to Sjöblom it is still unclear to historians whether there was actually any designated ship commander on Kronan with overall responsibility.[57]

History as a shipwreck

The total cost of Kronan was estimated at 326,000 silver dalers in contemporary currency, and about half of the cost, 166,000 dalers, lay just in the armaments. It was therefore in the interest of the Swedish navy to salvage as many of the cannons as possible. In the early 1660s almost all the guns from Vasa had been brought up through greatly improved salvaging technology. Commander Paul Rumpf and Admiral Hans Wachtmeister were put in charge of the salvage of Kronan's cannons. With the help of diving bells, they were able to raise 60 cannons worth 67,000 daler in the eight short diving seasons during the summers of 1679–86, beginning as soon as the war with Denmark had ended. In the 1960s, diving expert Bo Cassel made some successful descents to Vasa with a diving bell made according to 17th century specifications. In the summer of 1986, further experiments were done on Kronan. The tests proved successful and the conclusion was that the 17th century operations must have required considerable experience, skill and favorable weather conditions.[58] Though the conditions off Öland were often difficult, with cold water and unpredictable weather, and required a large crew, the expedition were very profitable. Historian Björn Axel Johansson has calculated that the total cost for the entire crew for all eight diving seasons was less than 2,000 dalers, the value of just one of Kronan's 36-pounder guns.[59]

Rediscovery

The marine engineer and amateur historian Anders Franzén had searched for old Swedish wrecks in the Baltic since the 1940s and became nationally renowned after he located Vasa, a prestige ship of Gustavus Adolphus's navy that sank only 20 minutes into her maiden voyage in Stockholm in 1628. Kronan was one of several famous shipwrecks that was on a list of potential wrecksites that he had compiled. For almost 30 years Franzén and others scoured archives and probed the seabed off the west coast of Öland. During the 1950s and 1960s the team searched off Hulterstad by dragging, and later followed up with sonar scans. In 1971 planks believed to belong Kronan were located, but the lead could not be followed up properly at the time. Later in the 1970s the search area was narrowed down with a sidescan sonar and a magnometer, an instrument that detects the presence of iron. With the combination of the two instruments the team managed to pin down a likely location, and in early August 1980, underwater cameras were sent down to reveal the first pictures of Kronan.[60]

Archaeology

The remains of Kronan lie at a depth of 26 m (85 ft), 6 km (3.7 mi) east of the village Hulterstad off the east coast of Öland. Since her rediscovery in 1980, there have been annual summer diving expeditions to the site of the wreck. By Baltic Sea standards, the conditions are in many ways advantageous for underwater archaeological work; the wrecksite is some distance from land, away from the regular shipping lanes, and has not been affected by pollution either from land or from excessive growth of marine vegetation. The line of sight, especially in early summer, is good and can be up to 20 m. The seabed consists of mostly infertile sand, which reflects much of sunlight from the surface. This factor has greatly improved the surveying and documentation of the site with underwater cameras. Around 85% of the wrecksite has been charted so far and Kronan has become one of the most extensive and well-publicized maritime archaeological projects in the Baltic Sea.[62]

Finds

Over 30,000 artifacts from Kronan have so far been salvaged and cataloged. There has been a great variety of object with everything from bronze cannons of up to four tonnes to small eggshell fragments.[62] There have been several discoveries of considerable importance, some of unique historical and archaeological value. One of the first finds was a small table cabinet with nine drawers containing navigational instruments, pipe-cleaning tools, cutlery and writing utensils, objects that most likely belonged to one of the officers.[63] As a flagship, Kronan carried a large amount of cash in the form of silver coins. Besides wages for the crew, a war chest was required for large, unforeseen expenses. In 1982, a collection of 255 minted gold coins was found, most of them ducats. The origin of the individual coins varied considerable, with locations such as Cairo, Reval (modern-day Tallinn) and Seville. Another 46 ducats were found in the summer of 2000.[64] The coin collection is likely the largest gold treasure ever encountered on Swedish soil, though it was not quite enough to cover large expenses, which has led to the assumption that they were the personal property of Admiral Lorentz Creutz's.[65] In 1989, over 900 silver coins were found in the remains of the orlop, at the time the largest silver coin collection ever found in Sweden. In 2005, a much larger cache of nearly 6,200 coins was discovered and in 2006 yet another with over 7,000 coins.[66] The silver treasure of 2005 consisted almost entirely of 4 öre-coins minted in 1675, which represented over 1% of the entire production of 4 öre-coins of that year.[67]

A number of musical instruments have been found, including a trumpet, three violins and a viola da gamba, all expensive objects that most likely belonged either to the officers or the trumpeters. One of the trumpeters on board was most likely in possession of a particularly fine instrument made in Germany since he was a member of the admiral's musical ensemble. Another remnant of the officers' personal stores was discovered in 1997, consisting of a woven basket filled with tobacco and expensive imported foodstuffs and spices, including ginger, plums, grapes and cinnamon quills.[68]

Approximately 7% of the finds consist of textiles. Much of the clothing, particularly those of the officers and their personal servants, is well preserved and has provided information on clothing manufacture during the late 17th century, something that has otherwise been difficult to research based only on depictions.[69]

See also

- Mary Rose, an English 16th century carrack that was salvaged in 1982

- La Belle (ship), the wreck of a French merchant ship salvaged in 1997

Notes

- ^ The names mean "the crown" and "the great crown" respectively. For information on modern standardization of the naming, see Anders Franzén in Johansson (1985), p. 9; Lundgren (1997), p. 8.

- ^ See Jan Glete (2002) War and the State in Early Modern Europe: Spain, the Dutch Republic and Sweden as Fiscal-Military States, 1500–1600. Routledge, London. ISBN 0-415-22645-7 for an in-depth study.

- ^ Göran Rystad "Skånska kriget och kampen om hegemonin i Norden" in Rystad (2005), pp. 17–19

- ^ Göran Rystad "Skånska kriget och kampen om hegemonin i Norden" in Rystad (2005), pp. 20–21

- ^ Glete (1993), s. 173–178.

- ^ Glete (1993), p. 176.

- ^ Finn Askgaard, "Kampen till sjöss" in Rystad (2005), p. 172

- ^ Anders Nilsson in Johansson (1985), pp. 52–53.

- ^ Anders Nilsson in Johansson (1985), pp. 38–39.

- ^ Glete (1999), p. 17

- ^ Kalmar County Museum, Official Kronan website. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ Glete (1999)

- ^ a b Glete (2002)

- ^ Anders Sandström, "Klar för strid" in Johansson (1985), pp. 122–123.

- ^ Gunnar Grandin, "Slaget den 26 maj" in Johansson (2005), p. 127.

- ^ Soop (2007), pp. 136–38.

- ^ Soop (2007), pp. 136–138; quotes from p. 138.

- ^ Lundgren (1997), pp. 9–18

- ^ Lundgren (1997), p. 10

- ^ Lundgren (1997), pp. 19–39

- ^ Lundgren (1997), pp. 9–10; Anders Franzén, "Kronan går av stapeln 1668" in Johansson (1985), s. 48–49.

- ^ Lundgren (1997), p. 19.

- ^ The Swedish army had only recently introduced standardized uniforms, something that was still uncommon in most of Europe.

- ^ Kronanprojektet (2008), s. 7–9.

- ^ The rule of Charles XI and Charles XII 1654–1718 is often referred to as the "Carolingian Period " (karolinska tiden) in Swedish history writing.

- ^ Pousette (2009), p. 107.

- ^ Pousette (2009), p. 107 (Zettersten, se även Asker, Hur riket styrdes)

- ^ Pousette (2009), s. 111–12.

- ^ All four were regalskepp (usually translated as "royal ships"), which were the largest in the fleet and usually named after pieces of the regalia of Sweden.

- ^ Original quote bonddrängar doppade i saltvatten in Gunnar Grandin, "Flottans nyckelroll" in Johansson (1985), p. 101.

- ^ Gunnar Grandin, "Stenbock betalar sjötåget" in Johansson (1985), pp. 108–109; Kurt Lundgren, "Flottan sågas genom isen" in Johansson (1985), pp. 110–111; Sjöblom (2003), p. 223.

- ^ Glete (2010), pp. 302, 305

- ^ Kurt Lundgren, "Flottan sågas genom isen" in Johansson (1985), s. 110–11.

- ^ Gunnar Grandin "Gotland invanderas", "Flottan löper ut" in Johansson (1985), pp. 114–15, 118–19.

- ^ Sjöblom (2003), pp. 225–26.

- ^ Sjöblom (2003), p. 226.

- ^ Kronanprojektet (2007), s. 4

- ^ During (1997) s. 594; Sjöblom (2003), s. 227.

- ^ Villner (2012), pp. 38–39

- ^ a b Sjöblom (2003), p. 228

- ^ Einarsson (2005) "Likplundring i Hulterstad", p. 56.

- ^ Björn Axel Johansson, "I Creutz ficka", in Johansson (1985) p. 165.

- ^ Glete (2010), p. 190

- ^ Glete (2010), p. 563

- ^ Glete (2010), p. 566

- ^ Original quote: "en del av våra sjöofficerare sig så lachement förhållit [att de] riksens säkerhet, välfärd och försvar ... ställt uti den högsta hazard"; "ett så stort crimen strängeligen bör straffas"; Lundgren (2001), pp. 5–6.

- ^ Lundgren (2001), p. 72.

- ^ Einarsson (2001), pp. 9–12

- ^ Lundgren (1997), pp. 107–11

- ^ Lundgren (2001), p. 51.

- ^ Lundgren (2001), s. 235.

- ^ See Asker (2005), p. 29; Björlin (1885); Gyllengranat (1840); Isacson (2000), pp. 11–12; Unger (1909), p. 234; Zettersten (1903), p. 478.

- ^ Gunnar Grandin, "Nervkris eller chansning" in Johansson (1985), pp. 144–145.

- ^ Ericson Wolke (2009), p. 115; Sjöblom (2003), p. 227

- ^ Asker (2005), pp. 29–30

- ^ Einarsson (2001), p. 13

- ^ Sjöblom (2003), p. 227

- ^ Johansson (1993), pp. 129–133

- ^ Johansson (1993), pp. 156–158

- ^ Ahlberg, Börjesson, Franzén & Grisell, "Kronan hittas", in Johansson (1985), pp. 192–205

- ^ Kronanprojektet (1992)

- ^ a b Kronanprojektet (2008)

- ^ Einarsson (2001), p. 30

- ^ Einarsson (2001), pp. 33–34

- ^ A gold treasure containing several hundred gold coins was found during a housing construction by Stortorget in Stockholm's Old Town in 1804, but since all but one coin was sold off, it is not know whether it was larger than the Kronan hoard; Golabiewsky Lannby (1985), pp. 6–8, 11.

- ^ Gainsford & Jonsson (2008)

- ^ Einarsson (2005) "Ännu en silverskatt påträffad", p. 15

- ^ Einarsson (2001), pp. 31, 36

- ^ Pousette (2009)

References

- Template:Sv Asker, Björn (2005) "Sjöofficerare till sjöss och till lands" in Björn Asker (editor) Stormakten som sjömakt: marina bilder från karolinsk tid. Historiska media, Lund. ISBN 91-85057-43-6; pp. 29–32.

- Template:Sv Björlin, Gustaf, (1885) Kriget mot Danmark 1675–1679: läsning för ung och gammal. Norstedt, Stockholm.

- During [Düring], Ebba, (1997) "Specific Skeletal Injuries Observed on the Human Skeletal Remains from the Swedish Seventeenth Century Man-of-War, Kronan" in International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, vol. 7; pp. 591–594.

- Template:Sv Einarsson, Lars (2001) Kronan. Kalmar läns museum, Kalmar. ISBN 91-85926-48-5

- Template:Sv Einarsson, Lars (2005) "Likplundring i Hulterstad år 1676" in Kalmar län: meddelande från Kalmar läns hembygdsförbund och Stiftelsen Kalmar läns museum. ISSN 0451-2715; pp. 52–58.

- Template:Sv Einarsson, Lars (2005) "Ännu en silverskatt påträffad i vraket av regalskeppet Kronan" in Myntstudier, vol. 2005:3. ISSN 1652-2303.; pp. 14–16.

- Template:Sv Ericson Wolke, Lars (2009) "En helt ny flotta – sjökrigen under 1600-talets sista årtionde", in Ericson Wolke & Hårdstedt, Svenska sjöslag. Medströms förlag, Stockholm. ISBN 978-91-7329-030-2

- Template:Sv Gainsford, Sara & Jonsson, Kenneth (2008) "2005 års skatt från regalskeppet Kronan" in Myntstudier vol. 2008:3. ISSN 1652-2303; pp. 3–17.

- Glete, Jan (1993) Navies and Nations: Warships, Navies and State Building in Europe and America, 1500–1680, Volume One. Almqvist & Wiksell International, Stockholm. ISBN 91-22-01565-5

- Template:Sv Glete, Jan (1999) "Hur stor var Kronan? Något om stora örlogsskepp i Europa under 1600-talets senare hälft" in Forum Navale 55. Sjöhistoriska samfundet, Stockholm; pp. 17–25

- Glete, Jan (2010) Swedish Naval Administration, 1521–1721: Resource Flows and Organisational Capabilities. Brill, Leiden. ISBN 978-90-04-17916-5

- Golabiewski Lannby, Monica, (1988) The Goldtreasure from the Royal Ship Kronan at the Kalmar County Museum. Kalmus, Kalmar. ISBN 91-85926-09-4

- Template:Sv Gyllengranat, Carl August (1840) Sveriges sjökrigs-historia i sammandrag. Karlskrona, Ameen.

- Template:Sv Isacson, Glaes-Göran (2000) Skånska kriget 1675–1679, Historiska media, Lund. ISBN 91-88930-87-4

- Template:Sv Johansson, Björn Axel (editor, 1985) Regalskeppet Kronan. Trevi, Stockholm. ISBN 91-7160-740-4

- Template:Sv Johansson, Björn Axel (1993), "Med dykarklocka på regalskeppet Kronan" in Ryde, Torsten (editor) "-se över relingens rand!" Festskrift till Anders Franzén. ISBN 91-7054-711-4; pp, 124–158

- Template:Sv Kronanprojektet (1992) Rapport över 1991 års marinarkeologiska undersökningar vid vrakplatsen efter regalskeppet Kronan. Kalmar läns museum, Kalmar.

- Template:Sv Kronanprojektet (2007) Rapport över 2006 års marinarkeologiska undersökningar vid vrakplatsen efter regalskeppet Kronan. Kalmar läns museum, Kalmar.

- Template:Sv Kronanprojektet (2008) Rapport över 2007 års marinarkeologiska undersökningar vid vrakplatsen efter regalskeppet Kronan. Kalmar läns museum, Kalmar.

- Template:Sv Lundgren, Kurt (1997) Stora Cronan: Byggandet Slaget Plundringen av Öland En genomgång av historiens källmaterial. Lenstad Bok & Bild, Kristianstad. ISBN 91-973261-5-1.

- Template:Sv Lundgren, Kurt (2001) Sjöslaget vid Öland. Vittnesmål – dokument 1676–1677. Lingstad Bok & Bild, Kalmar. ISBN 91-631-1292-2

- Template:Sv Pousette, Mary (2009) "Klädd ombord" in Schoerner, Katarina (editor) Skärgård och örlog: nedslag i Stockholms skärgårds tidiga historia. Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien, Konferenser 71. Stockholm. ISBN 978-91-7402-388-6

- Template:Sv Rystad, Göran (editor, 2005) Kampen om Skåne. Historiska media, Lund. ISBN 91-85057-05-3

- Template:Sv Sjöblom, Olof (2003) "Slaget vid Öland 1676: Kronan går under" in Ericson [Wolke], Hårdstedt, Iko, Sjöblom & Åselius, Svenska slagfält. Wahlström & Widstrand, Stockholm. ISBN 91-46-20225-0

- Template:Sv Soop, Hans (2007) Flytande palats: utsmyckning av äldre svenska örlogsfartyg. Signum, Stockholm. ISBN 978-91-87896-83-5

- Template:Sv Unger, Gunnar (1909) Illustrerad Svensk Sjökrigshistoria omfattande tiden intill 1680. Bonnier, Stockholm.

- Template:Sv Villner, Katarina (2012) Under däck: Mary Rose – Vasa – Kronan. Medström, Stockholm. ISBN 978-91-7329-108-8

- Template:Sv Zettersten, Axel (1903) Svenska flottans historia åren 1635–1680. Norrtälje tidnings boktryckeri, Norrtälje.

Further reading

- Einarsson, Lars (1994) "Present maritime archaeology in Sweden: the case of Kronan" in Schokkenbroek, J.C.A. (editor), Plying between Mars and Mercury: political, economic and cultural links between the Netherlands and Sweden during the Golden age: papers for the Kronan symposium, Amsterdam, 19 November 1993. NIVE for the Swedish Embassy, The Hague.; pp. 41–47

- Einarsson, Lars & Morzer-Bruyns, W.F.J. (2003) "A cross-staff from the wreck of the Kronan (1676)" in International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, v. 32; pp. 53–60

- Franzén, Anders (1981) HMS Kronan : The Search for a Great 17th Century Swedish warship. Royal instititue of technology library [Tekniska högskolans bibliotek], Stockholm.

External links

- Officiell website – hosted by Kalmar County Museum

- Kalmar läns museum – organizers of the Kronan Projekt and the site of several permanent exhibitions of finds from the ship

- Osteological and Microanalytical Investigation of the Human Skeletal Remains (a presentation of the study)

- Kronan at the Nordic Underwater Archaeology website

56°26′58″N 16°40′20″E / 56.44944°N 16.67222°E