Anorexia nervosa: Difference between revisions

SandyGeorgia (talk | contribs) |

SandyGeorgia (talk | contribs) →F 50.0: completely plagiarized. cut and pasted. someone else can rewrite it |

||

| Line 79: | Line 79: | ||

* Severe: BMI of 15–15.99 |

* Severe: BMI of 15–15.99 |

||

* Extreme: BMI of less than 15 |

* Extreme: BMI of less than 15 |

||

====F 50.0==== |

|||

A disorder characterized by deliberate weight loss, induced and sustained by the patient. It occurs most commonly in adolescent girls and young women, but adolescent boys and young men may also be affected, as may children approaching puberty and older women up to the menopause. The disorder is associated with a specific psychopathology whereby a dread of fatness and flabbiness of body contour persists as an intrusive overvalued idea, and the patients impose a low weight threshold on themselves. There is usually undernutrition of varying severity with secondary endocrine and metabolic changes and disturbances of bodily function. The symptoms include restricted dietary choice, excessive exercise, induced vomiting and purgation, and use of appetite suppressants and diuretics.<ref>[http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online2003/fr-icd.htm?gf50.htm+ "ICD-10:"]. who.int</ref> |

|||

===Investigations=== |

===Investigations=== |

||

Revision as of 23:09, 9 April 2015

Error: no context parameter provided. Use {{other uses}} for "other uses" hatnotes. (help).

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Anorexia nervosa | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology |

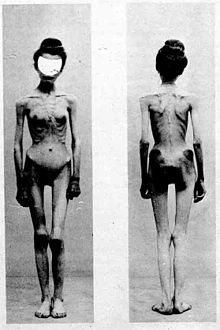

Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by food restriction, odd eating habits or rituals, obsession with having a thin figure, and an irrational fear of weight gain. It is accompanied by a distorted body self-perception, and typically involves excessive weight loss.

Due to their fear of gaining weight, individuals with this disorder restrict the amount of food they consume. Outside of medical literature, the terms anorexia nervosa and anorexia are often used interchangeably; however, anorexia is simply a medical term for lack of appetite; in AN, appetite dysregulation or alterations in the sensation of fullness are suspected.[1]

Anorexia nervosa is often coupled with a distorted self image[2] which may be maintained by various cognitive biases[3] that alter how individuals evaluate and think about their body, food, and eating. People with anorexia nervosa often view themselves as overweight or not thin enough even when they are underweight.[4]

Anorexia nervosa is diagnosed predominantly in women.[5] In 2013 it resulted in about 600 deaths globally up from 400 deaths in 1990.[6] It is a serious health condition with a high incidence of comorbidity and similarly high mortality rate to serious psychiatric disorders.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder that is characterized by attempts to lose weight, to the point of self-starvation. A person with anorexia nervosa may exhibit a number of signs and symptoms, the type and severity of which may vary in each case and may be present but not readily apparent.[7]

Anorexia nervosa, and the associated malnutrition that results from self-imposed starvation, can cause severe complications in every major organ system in the body.[8] Hypokalaemia, a drop in the level of potassium in the blood, is a sign of anorexia nervosa.[9][1] A significant drop in potassium can cause abnormal heart rhythms, constipation, fatigue, muscle damage and paralysis.[10]

Symptoms of AN may include:

- Refusal to maintain a normal body mass index for one's age

- Amenorrhea, a symptom that occurs after prolonged weight loss; causes menses to stop, hair becomes brittle, and skin becomes yellow and unhealthy

- Fearful of even the slightest weight gain and takes all precautionary measures to avoid weight gain and becoming overweight

- Obvious, rapid, dramatic weight loss to at least 15% under normal body weight[11]

- Lanugo: soft, fine hair growing on the face and body[9]

- Obsession with calories and fat content of food

- Preoccupation with food, recipes, or cooking; may cook elaborate dinners for others, but not eat the food themselves

- Food restriction despite being underweight

- Food rituals, such as cutting food into tiny pieces, refusing to eat around others, hiding or discarding food

- Purging: May use laxatives, diet pills, ipecac syrup, or water pills; may engage in self-induced vomiting; may run to the bathroom after eating in order to vomit and quickly get rid of ingested calories

- Excessive exercise[12]

- Perception of self as overweight despite being told by others they are too thin

- Intolerance to cold and frequent complaints of being cold; body temperature may lower (hypothermia) in an effort to conserve energy[13]

- Hypotension and/or orthostatic hypotension

- Bradycardia or tachycardia

- Depression

- Solitude: may avoid friends and family; becomes withdrawn and secretive

- Abdominal distension

- Halitosis (from vomiting or starvation-induced ketosis)

- Dry hair and skin, as well as hair thinning

- Fatigue

- Rapid mood swings

Diagnosis

A diagnostic assessment may be conducted by a suitably trained general practitioner, or by a psychiatrist or psychologist, who records the person's current circumstances, biographical history, current symptoms, and family history. The assessment also includes a mental state examination, which is an assessment of the person's current mood and thought content, focussing on views on weight and patterns of eating. There are multiple medical conditions, such as viral or bacterial infections, hormonal imbalances, neurodegenerative diseases and brain tumors which may mimic psychiatric disorders including anorexia nervosa.

DSM-5 and ICD-10 criteria

Anorexia nervosa is classified as an Axis I disorder in the latest revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders (DSM 5), published by the American Psychiatric Association. Relative to the previous version (DSM-IV-TR) there have been several changes made to the criteria for anorexia nervosa, most notably that of the amenorrhea criterion being removed.[14][15]

Subtypes

There are two subtypes of AN:[8][16]

- Binge-eating/purging type: Individual utilizes binge eating or displays purging behavior as a means for losing weight.[16]

- Restricting type: the individual uses restricting food intake, fasting, diet pills, and/or exercise as a means for losing weight.[8]

Levels of severity

Body mass index (BMI) is used by the DSM-V as an indicator of the level of severity of anorexia nervosa. The DSM-V states these as follows:[17]

- Mild: BMI of 17–17.99

- Moderate: BMI of 16–16.99

- Severe: BMI of 15–15.99

- Extreme: BMI of less than 15

Investigations

Medical tests to check for signs of physical deterioration in anorexia nervosa may be performed by a general physician or psychiatrist, including:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): a test of the white blood cells, red blood cells and platelets used to assess the presence of various disorders such as leukocytosis, leukopenia, thrombocytosis and anemia which may result from malnutrition.[18]

- Urinalysis: a variety of tests performed on the urine used in the diagnosis of medical disorders, to test for substance abuse, and as an indicator of overall health[19]

- Chem-20: Chem-20 also known as SMA-20 a group of twenty separate chemical tests performed on blood serum. Tests include cholesterol, protein and electrolytes such as potassium, chlorine and sodium and tests specific to liver and kidney function.[20]

- Glucose tolerance test: Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) used to assess the body's ability to metabolize glucose. Can be useful in detecting various disorders such as diabetes, an insulinoma, Cushing's Syndrome, hypoglycemia and polycystic ovary syndrome[21][22]

- Serum cholinesterase test: a test of liver enzymes (acetylcholinesterase and pseudocholinesterase) useful as a test of liver function and to assess the effects of malnutrition[23]

- Liver Function Test: A series of tests used to assess liver function some of the tests are also used in the assessment of malnutrition, protein deficiency, kidney function, bleeding disorders, and Crohn's Disease.[24]

- Lh response to GnRH: Luteinizing hormone (Lh) response to gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH): Tests the pituitary glands' response to GnRh a hormone produced in the hypothalamus. Central hypogonadism is often seen in anorexia nervosa cases.[25]

- Creatine Kinase Test (CK-Test): measures the circulating blood levels of creatine kinase an enzyme found in the heart (CK-MB), brain (CK-BB) and skeletal muscle (CK-MM).[26][27]

- Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) test: urea nitrogen is the byproduct of protein metabolism first formed in the liver then removed from the body by the kidneys. The BUN test is primarily used to test kidney function. A low BUN level may indicate the effects of malnutrition.[28]

- BUN-to-creatinine ratio: A BUN to creatinine ratio is used to predict various conditions. A high BUN/creatinine ratio can occur in severe hydration, acute kidney failure, congestive heart failure, and intestinal bleeding. A low BUN/creatinine ratio can indicate a low protein diet, celiac disease, rhabdomyolysis, or cirrhosis of the liver.[29][30][31]

- Electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG): measures electrical activity of the heart. It can be used to detect various disorders such as hyperkalemia[32]

- Electroencephalogram (EEG): measures the electrical activity of the brain. It can be used to detect abnormalities such as those associated with pituitary tumors[33][34]

- Thyroid Screen TSH, t4, t3 :test used to assess thyroid functioning by checking levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), thyroxine (T4), and triiodothyronine (T3)[35]

- Parathyroid hormone (PTH) test: tests the functioning of the parathyroid by measuring the amount of (PTH) in the blood. It is used to diagnose parahypothyroidism. PTH also controls the levels of calcium and phosphorus in the blood (homeostasis).This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015)

Differential diagnoses

A variety of medical and psychological conditions have been misdiagnosed as anorexia nervosa; in some cases the correct diagnosis was not made for more than ten years.

The distinction between the diagnoses of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) is often difficult to make as there is considerable overlap between patients diagnosed with these conditions. Seemingly minor changes in a patient's overall behavior or attitude can change a diagnosis from anorexia: binge-eating type to bulimia nervosa. A main factor differentiating binge-purge anorexia from bulimia is the gap in physical weight. Someone with bulimia nervosa is ordinarily at a healthy weight, or slightly overweight. Someone with binge-purge anorexia is commonly underweight.[36] It is not unusual for a person with an eating disorder to "move through" various diagnoses as their behavior and beliefs change over time.[37]

Comorbidity

Other psychological issues may factor into anorexia nervosa; some fulfill the criteria for a separate Axis I diagnosis or a personality disorder which is coded Axis II and thus are considered comorbid to the diagnosed eating disorder. Some people have a previous disorder which may increase their vulnerability to developing an eating disorder and some develop them afterwards.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

The presence of Axis I and/or Axis II psychiatric comorbidity has been shown to affect the severity and type of anorexia nervosa symptoms in both adolescents and adults.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) are highly comorbid with AN, particularly the restrictive subtype.[38] Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder is linked with more severe symptomatology and worse prognosis.[39] The causality between personality disorders and eating disorders has yet to be fully established.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

Other comorbid conditions include depression,[40] alcoholism,[41] borderline and other personality disorders,[42][43] anxiety disorders,[44] attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,[45] and body dysmorphic disorder (BDD).[46] Depression and anxiety are the most common comorbidities,[47] and depression is associated with a worse outcome.[47]

Autism spectrum disorders have a higher prevalence among people with eating disorders than in the general population.[48] Zucker et al. (2007) proposed that conditions on the autism spectrum make up the cognitive endophenotype underlying anorexia nervosa and appealed for increased interdisciplinary collaboration.[37]

Causes

There is evidence for biological, psychological, developmental, and sociocultural risk factors, but the exact cause of eating disorders is unknown.[49]

Biological

- Serotonin dysregulation; brain imaging studies implicate alterations of 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors and the 5-HT transporter.[49] Alterations of these circuits may affect mood and impulse control as well as the motivating and hedonic aspects of feeding behavior.[50] Starvation has been hypothesized to be a response to these effects, as it is known to lower tryptophan and steroid hormone metabolism, which might reduce serotonin levels at these critical sites and ward off anxiety.[50]

- Genetics: anorexia nervosa is highly heritable.[49] Twin studies have shown a heritability rate of between 28 and 58%.[51] Association studies have been performed, studying 128 different polymorphisms related to 43 genes including genes involved in regulation of eating behavior, motivation and reward mechanics, personality traits and emotion. Consistent associations have been identified for polymorphisms associated with agouti-related peptide, brain derived neurotrophic factor, catechol-o-methyl transferase, SK3 and opioid receptor delta-1.[52]

- Addiction to the chemicals released in the brain during starving and physical activity;[53][54] people affected with anorexia often report getting some sort of high from not eating. The effect of food restriction and intense activity causes symptoms similar to anorexia in female rats,[53] though it is not explained why this addiction affects only females.

- Obstetric complications: prenatal and perinatal complications may factor into the development of anorexia nervosa, such as maternal anemia, diabetes mellitus, preeclampsia, placental infarction, and neonatal cardiac abnormalities. Neonatal complications may also have an influence on harm avoidance, one of the personality traits associated with the development of AN.This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015)

- Orexin; orexin is a neurotransmitter that regulates appetite and is responsible for increasing the craving for food.[55]

- Infections: Some people are hypothesized to have developed anorexia abruptly as a reaction to a streptococcus or mycoplasma infection. Pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS) is a hypothesis describing children who have abrupt, dramatic onset of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or anorexia nervosa coincident with the presence of two or more neuropsychiatric symptoms.[56]

- Zinc deficiency may play a role in anorexia. It is not thought responsible for causation of the initial illness but there is evidence that it may be an accelerating factor that deepens the pathology of the anorexia. A 1994 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial showed that zinc (14 mg per day) doubled the rate of body mass increase compared to patients receiving the placebo.[57]

Studies have hypothesized the continuance of disordered eating patterns may be epiphenomena of starvation. The results of the Minnesota Starvation Experiment showed normal controls exhibit many of the behavioral patterns of anorexia nervosa (AN) when subjected to starvation. This may be due to the numerous changes in the neuroendocrine system, which results in a self-perpetuating cycle.[58][59][60]

Another hypothesis is that anorexia nervosa is more likely to occur in populations in which obesity is more prevalent, and results from a sexually selected evolutionary drive to appear youthful in populations in which size becomes the primary indicator of age.[61]

Anorexia nervosa is more likely to occur in a person's pubertal years. Some explanatory hypotheses for the rising prevalence of eating disorders in adolescence are "increase of adipose tissue in girls, hormonal changes of puberty, societal expectations of increased independence and autonomy that are particularly difficult for anorexic adolescents to meet; [and] increased influence of the peer group and its values." [62]

Psychological

Early theories of the cause of anorexia linked it to childhood sexual abuse or dysfunctional families;[63][64] evidence is conflicting, and well-designed research is needed.[49]

Sociological

Anorexia nervosa has been increasingly diagnosed since 1950;[65] the increase has been linked to vulnerability and internalization of body ideals.[62] People in professions where there is a particular social pressure to be thin (such as models and dancers) were more likely to develop anorexia,

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

and those with anorexia have much higher contact with cultural sources that promote weight loss.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

This trend can also be observed for people who partake in certain sports, such as jockeys and wrestlers.[66] There is a higher incidence and prevalence of anorexia nervosa in sports with an emphasis on aesthetics, where low body fat is advantageous, and sports in which one has to make weight for competition.[67]

- Media effects

Constant exposure to media that presents body ideals may constitute a risk factor for body dissatisfaction and anorexia nervosa. The cultural ideal for body shape for men versus women continues to favor slender women and athletic, V-shaped muscular men. A 2002 review found that the magazines most popular among people aged 18 to 24 years, those read by men, unlike those read by women, were more likely to feature ads and articles on shape than on diet.[unreliable medical source?][68] Body dissatisfaction and internalization of body ideals are risk factors for anorexia nervosa that threaten the health of both male and female populations.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

Websites that stress the importance of attainment of body ideals extol and promote anorexia nervosa through the use of religious metaphors, lifestyle descriptions, "thinspiration" or "fitspiration" (inspirational photo galleries and quotes that aim to serve as motivators for attainment of body ideals).[69] Pro-anorexia websites reinforce internalization of body ideals and the importance of their attainment.[69]

Treatment

There is no conclusive evidence that any particular treatment for anorexia nervosa works better than others; however, there is enough evidence to suggest that early intervention and treatment are more effective.[70] Treatment for anorexia nervosa tries to address three main areas.

- Restoring the person to a healthy weight;

- Treating the psychological disorders related to the illness;

- Reducing or eliminating behaviours or thoughts that originally led to the disordered eating.[71]

Although restoring the person's weight is the primary task at hand, optimal treatment also includes and monitors behavioral change in the individual as well.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

Not all anorexia nervosa patients recover completely: about 20% develop anorexia nervosa as a chronic disorder.[70] If anorexia nervosa is not treated, serious complications such as heart conditions[7] and kidney failure can arise and eventually lead to death.[72]

Some remedies are proven to not have any value in resolving anorexia. "Incarceration in hospital" prohibits patients from many basic rights, such as using the bathroom independently. Therefore, it has been seen as catalytic in increasing weight and pushing patients away from the path to recovery.[73]

Dietary

Diet is the most essential factor to work on in patients with anorexia nervosa, and must be tailored to each patient's needs. Food variety is important when establishing meal plans as well as foods that are higher in energy density.[74] Patients must consume adequate calories, starting slowly, and increasing at a measured pace.[12]

Medication

Pharmaceuticals have limited benefit for anorexia itself.[75]

Therapy

Family-based treatment (FBT) has been shown to be more successful than individual therapy.[76] Various forms of family-based treatment have been proven to work in the treatment of adolescent AN including conjoint family therapy (CFT), in which the parents and child are seen together by the same therapist, and separated family therapy (SFT) in which the parents and child attend therapy separately with different therapists.[76] Proponents of Family therapy for adolescents with AN assert that it is important to include parents in the adolescent's treatment.[76]

A four- to five-year follow up study of the Maudsley family therapy, an evidence-based manualized model, showed full recovery at rates up to 90%.[77] Although this model is recommended by the NIMH,[78] critics claim that it has the potential to create power struggles in an intimate relationship and may disrupt equal partnerships.[79]

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is useful in adolescents and adults with anorexia nervosa;[80] acceptance and commitment therapy is a type of CBT, which has shown promise in the treatment of AN.[81] Cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) is used in treating anorexia nervosa.[82]

Prognosis

AN has the highest mortality rate of any psychological disorder.[76] The mortality rate is 11 to 12 times higher than expected, and the suicide risk is 56 times higher; half of women with AN achieve a full recovery, while an additional 20–30% may partially recover.[1] The average number of years from onset to remission of AN is seven for women and three for men. After ten to fifteen years, 70% of people no longer meet the diagnostic criteria, but many still continue to have eating-related problems.[83]

Alexithymia has an impact on treatment outcome.[75] Recovery is also viewed on a spectrum rather than black and white. According to the Morgan-Russell criteria patients can have a good, intermediate, or poor outcome. Even when a patient is classified as having a "good" outcome, weight only has to be within 15% of average and normal menstruation must be present in females. The good outcome also excludes psychological health. Recovery for patients with anorexia nervosa is undeniably positive, but recovery does not mean a return to normal.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

Complications

Anorexia nervosa can have serious implications if its duration and severity are significant and if onset occurs before the completion of growth, pubertal maturation, or the attainment of peak bone mass.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

Complications specific to adolescents and children with anorexia nervosa can include the following:

- Growth retardation – height gain may slow and can stop completely with severe weight loss or chronic malnutrition. In such cases, provided that growth potential is preserved, height increase can resume and reach full potential after normal intake is resumed.

Height potential is normally preserved if the duration and severity of illness are not significant and/or if the illness is accompanied with delayed bone age (especially prior to a bone age of approximately 15 years), as hypogonadism may negate the deleterious effects of undernutrition on stature by allowing for a longer duration of growth compared to controls.This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015)

In such cases, appropriate early treatment can preserve height potential and may even help to increase it in some post-anorexic subjects due to the aforementioned reasons in addition to factors such as long-term reduced estrogen-producing adipose tissue levels compared to premorbid levels.This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015)This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) - Pubertal delay or arrest – both height gain and pubertal development are dependent on the release of growth hormone and gonadotrophins (LH and FSH) from the pituitary gland. Suppression of gonadotrophins in patients with anorexia nervosa has frequently been documented.

In some cases, especially where onset is pre-pubertal, physical consequences such as stunted growth and pubertal delay are usually fully reversible.[84]This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) - Reduction of Peak Bone Mass – bone accretion is the highest during adolescence, and if onset of anorexia nervosa occurs during this time and stalls puberty, bone mass may remain low.This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015)

- Hepatic steatosis – fatty infiltration of the liver is an indicator of malnutrition in children.[85]

- Heart disease and arrythmias

- Neurological disorders- seizures, tremors

Relapse

Relapse occurs in approximately a third of inpatients, and is greatest in the first half-year to year-and-a-half after release from inpatient institutions.[5]

Epidemiology

Though anorexia is common among many groups in the United States, the disorder is more limited to the Western world.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

Anorexia has an average prevalence of 0.9% in women and 0.3% in men for the diagnosis in developed countries.[86] About three times as many women as men are affected.[5] The lifetime incidence of atypical anorexia nervosa, a form of ED-NOS in which not all of the diagnostic criteria for AN are met, is much higher, at 5–12%.[87]

The question of whether the incidence of AN is on the rise has been under debate. Most studies show that since at least 1970 the incidence of AN in adult women is fairly constant, while there is some indication that the incidence may have been increasing for girls aged between 14 and 20.[88] It is difficult to compare incidence rates at different times and possibly different locations due to changes in methods of diagnosing, reporting and changes in the population numbers, as evidenced on data from after 1970.[89][90]

Underrepresentation

Eating disorders are less reported in preindustrial, non-westernized countries than in Western countries. In Africa, not including South Africa, the only data presenting information about eating disorders occurs in case reports and isolated studies, not studies investigating prevalence. Data shows in research that in westernized civilizations, ethnic minorities have very similar rates of eating disorders, contrary to the belief that eating disorders predominantly occur in Caucasian people.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

Due to different standards of beauty for men and women, men are often not diagnosed as anorexic. Generally men who alter their bodies do so to be lean and muscular rather than thin. In addition, men who might otherwise be diagnosed with anorexia may not meet the DSM IV criteria for BMI since they have muscle weight, but have very little fat.[91] Men and women athletes are often overlooked as anorexic.[91] Research emphasizes the importance to take athletes' diet, weight and symptoms into account when diagnosing anorexia, instead of just looking at weight and BMI. For athletes, ritualized activities such as weigh-ins place emphasis on weight, which may promote the development of eating disorders among them.[citation needed] While women use diet pills, which is an indicator of unhealthy behavior and an eating disorder, men use steroids, which contextualizes the beauty ideals for genders. This also shows men having a preoccupation with their body, which is an indicator of an eating disorder.[49] In a Canadian study, 4% of boys in grade nine used anabolic steroids.[49] Anorexic men are sometimes referred to as manorexic.[92]

History

The term anorexia nervosa was coined in 1873 by Sir William Gull, one of Queen Victoria's personal physicians.[93] The term is of Greek origin: an- (ἀν-, prefix denoting negation) and orexis (ὄρεξις, "appetite"), translating literally to a nervous loss of appetite.[94]

The history of anorexia nervosa begins with descriptions of religious fasting dating from the Hellenistic era[95] and continuing into the medieval period. The medieval practice of self-starvation by women, including some young women, in the name of religious piety and purity also concerns anorexia nervosa; it is sometimes referred to as anorexia mirabilis.[96][97]

The earliest medical descriptions of anorexic illnesses are generally credited to English physician Richard Morton in 1689.[95] Case descriptions fitting anorexic illnesses continued throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.[98]

In the late 19th century anorexia nervosa became widely accepted by the medical profession as a recognized condition. In 1873, Sir William Gull, one of Queen Victoria's personal physicians, published a seminal paper which coined the term anorexia nervosa and provided a number of detailed case descriptions and treatments.[98] In the same year, French physician Ernest-Charles Lasègue similarly published details of a number of cases in a paper entitled De l'Anorexie Histerique.[citation needed]

Awareness of the condition was largely limited to the medical profession until the latter part of the 20th century, when German-American psychoanalyst Hilde Bruch published The Golden Cage: the Enigma of Anorexia Nervosa in 1978. Despite major advances in neuroscience,[99] Bruch's theories tend to dominate popular thinking. A further important event was the death of the popular singer and drummer Karen Carpenter in 1983, which prompted widespread ongoing media coverage of eating disorders.[citation needed]

See also

- List of people with anorexia nervosa

- Anti-fat bias

- Eating disorders and development

- Eating Recovery

- Hungry: A Mother and Daughter Fight Anorexia (book)

- Life-Size (novel)

- Marya Hornbacher

- Muscle dysmorphia

- National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders

- Orthorexia nervosa

- Pro-ana

- Weight phobia

- Sandra Lahire

References

- ^ a b c Miller KK (2013). "Endocrine effects of anorexia nervosa". Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 42 (3): 515–28. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2013.05.007. PMC 3769686. PMID 24011884.

- ^ Cooper MJ (2005). "Cognitive theory in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: progress, development and future directions". Clinical Psychology Review. 25 (4): 511–31. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.01.003. PMID 15914267.

- ^ Brooks S, Prince A, Stahl D, Campbell IC, Treasure J (2010). "A systematic review & meta-analysis of cognitive bias to food stimuli in people with disordered eating behaviour". Clinical Psychology. 31 (1): 37–51. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.09.006. PMID 21130935.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Attia E (2010). "Anorexia Nervosa: Current Status and Future Directions". Annual Review of Medicine. 61 (1): 425–35. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.050208.200745. PMID 19719398.

- ^ a b c Hasan TF, Hasan H (2011). "Anorexia nervosa: a unified neurological perspective". Int J Med Sci. 8 (8): 679–703. PMC 3204438. PMID 22135615.

- ^ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–171. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Surgenor LJ, Maguire S (2013). "Assessment of anorexia nervosa: an overview of universal issues and contextual challenges". J Eat Disord. 1 (1): 29. doi:10.1186/2050-2974-1-29. PMC 4081667. PMID 24999408.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c Strumia R (2009). "Skin signs in anorexia nervosa". Dermatoendocrinol. 1 (5): 268–70. PMC 2836432. PMID 20808514.

- ^ a b Walsh JM, Wheat ME, Freund K (2000). "Detection, evaluation, and treatment of eating disorders the role of the primary care physician". J Gen Intern Med. 15 (8): 577–90. PMC 1495575. PMID 10940151.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stargrove MB, Treasure J, McKee DL (2008). Herb, Nutrient, and Drug Interactions: Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Strategies. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 0323029647. Retrieved 2015-04-09.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Anorexia Nervosa". National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ a b Marzola E, Nasser JA, Hashim SA, Shih PA, Kaye WH (2013). "Nutritional rehabilitation in anorexia nervosa: review of the literature and implications for treatment". BMC Psychiatry. 13 (1): 290. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-13-290. PMC 3829207. PMID 24200367.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Haller E (1992). "Eating disorders. A review and update". The Western Journal of Medicine. 157 (6): 658–62. PMC 1022101. PMID 1475950.

- ^ Estour B, Galusca B, Germain N (2014). "Constitutional thinness and anorexia nervosa: a possible misdiagnosis?". Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 5: 175. doi:10.3389/fendo.2014.00175. PMC 4202249. PMID 25368605.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Feeding and eating disorders" (PDF). American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ a b Peat C, Mitchell JE, Hoek HW, Wonderlich SA (2009). "Validity and utility of subtyping anorexia nervosa". Int J Eat Disord. 42 (7): 590–4. doi:10.1002/eat.20717. PMC 2844095. PMID 19598270.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Singleton, Joanne K. (2014-11-12). Primary Care, Second Edition: An Interprofessional Perspective. Springer Publishing Company. ISBN 9780826171474. Retrieved 2015-04-09.

- ^ "CBC". MedlinePlus : U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ^ Urinalysis at Medline. Nlm.nih.gov (2012-01-26). Retrieved on 2012-02-04.

- ^ Chem-20 at Medline. Nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved on 2012-02-04.

- ^ Lee H, Oh JY, Sung YA, Chung H, Cho WY (2009). "The prevalence and risk factors for glucose intolerance in young Korean women with polycystic ovary syndrome". Endocrine. 36 (2): 326–32. doi:10.1007/s12020-009-9226-7. PMID 19688613.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Takeda N, Yasuda K, Horiya T, Yamada H, Imai T, Kitada M, Miura K (1986). "[Clinical investigation on the mechanism of glucose intolerance in Cushing's syndrome]". Nippon Naibunpi Gakkai Zasshi (in Japanese). 62 (5): 631–48. PMID 3525245.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Montagnese C, Scalfi L, Signorini A, De Filippo E, Pasanisi F, Contaldo F (2007). "Cholinesterase and other serum liver enzymes in underweight outpatients with eating disorders". The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 40 (8): 746–50. doi:10.1002/eat.20432. PMID 17610252.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Narayanan V, Gaudiani JL, Harris RH, Mehler PS (2010). "Liver function test abnormalities in anorexia nervosa—cause or effect". The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 43 (4): 378–81. doi:10.1002/eat.20690. PMID 19424979.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sherman BM, Halmi KA, Zamudio R (1975). "LH and FSH response to gonadotropin-releasing hormone in anorexia nervosa: Effect of nutritional rehabilitation". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 41 (1): 135–42. doi:10.1210/jcem-41-1-135. PMID 1097461.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Salvadori A, Fanari P, Ruga S, Brunani A, Longhini E (1992). "Creatine kinase and creatine kinase-MB isoenzyme during and after exercise testing in normal and obese young people". Chest. 102 (6): 1687–9. doi:10.1378/chest.102.6.1687. PMID 1446472.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Walder A, Baumann P (2008). "Increased creatinine kinase and rhabdomyolysis in anorexia nervosa". The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 41 (8): 766–7. doi:10.1002/eat.20548. PMID 18521917.

- ^ BUN at Medline. Nlm.nih.gov (2012-01-26). Retrieved on 2012-02-04.

- ^ Ernst AA, Haynes ML, Nick TG, Weiss SJ (1999). "Usefulness of the blood urea nitrogen/creatinine ratio in gastrointestinal bleeding". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 17 (1): 70–2. doi:10.1016/S0735-6757(99)90021-9. PMID 9928705.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sheridan AM, Bonventre JV (2000). "Cell biology and molecular mechanisms of injury in ischemic acute renal failure". Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 9 (4): 427–34. doi:10.1097/00041552-200007000-00015. PMID 10926180.

- ^ Nelsen DA (2002). "Gluten-sensitive enteropathy (celiac disease): more common than you think". American Family Physician. 66 (12): 2259–66. PMID 12507163.

- ^ Pepin J, Shields C (Feb 2012). "Advances in diagnosis and management of hypokalemic and hyperkalemic emergencies". Emerg Med Pract. 14 (2): 1–17. PMID 22413702.

- ^ "Electroencephalogram". Medline Plus. 26 January 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ Kameda K, Itoh N, Nakayama H, Kato Y, Ihda S (1995). "Frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity (FIRDA) in pituitary adenoma". Clinical EEG. 26 (3): 173–9. doi:10.1177/155005949502600309. PMID 7554305.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kumar MS, Safa AM, Deodhar SD, Schumacher OP (1977). "The relationship of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), thyroxine (T4), and triiodothyronine (T3) in primary thyroid failure". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 68 (6): 747–51. PMID 579717.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nolen-Hoeksema S (2014). "Eating disorders". Abnormal Psychology (Sixth ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education. p. 341. ISBN 978-0-07-803538-8.

- ^ a b Zucker NL, Losh M, Bulik CM, LaBar KS, Piven J, Pelphrey KA (2007). "Anorexia nervosa and autism spectrum disorders: guided investigation of social cognitive endophenotypes" (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 133 (6): 976–1006. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.976. PMID 17967091.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Godier LR, Park RJ (2014). "Compulsivity in anorexia nervosa: a transdiagnostic concept". Front Psychol. 5: 778. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00778. PMC 4101893. PMID 25101036.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Crane AM, Roberts ME, Treasure J (2007). "Are Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Traits Associated with a Poor Outcome in Anorexia Nervosa? A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials and Naturalistic Outcome Studies". International Journal of Eating Disorders. 40 (7): 581–8. doi:10.1002/eat.20419. PMID 17607713.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Casper RC (1998). "Depression and eating disorders". Depression and Anxiety. 8 (Suppl 1): 96–104. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1998)8:1+<96::AID-DA15>3.0.CO;2-4. PMID 9809221.

- ^ Zernig G, Saria A, Kurz M, O'Malley S (2000-03-24). Handbook of Alcoholism. CRC Press. p. 293. ISBN 9781420036961.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sansone RA, Levitt JL (2013-08-21). Personality Disorders and Eating Disorders: Exploring the Frontier. Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 1135442800.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Halmi KA (2013). "Perplexities of treatment resistance in eating disorders". BMC Psychiatry. 13: 292. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-13-292. PMC 3829659. PMID 24199597.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Swinbourne JM, Touyz SW (2007). "The co-morbidity of eating disorders and anxiety disorders: a review". European Eating Disorders Review : the Journal of the Eating Disorders Association. 15 (4): 253–74. doi:10.1002/erv.784. PMID 17676696.

- ^ Cortese S, Bernardina BD, Mouren MC (2007). "Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and binge eating". Nutrition Reviews. 65 (9): 404–11. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00318.x. PMID 17958207.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wilhelm S, Phillips KA, Steketee G (2012-12-18). Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Body Dysmorphic Disorder: A Treatment Manual. Guilford Press. p. 270. ISBN 9781462507900.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Berkman ND, Bulik CM, Brownley KA, Lohr KN, Sedway JA, Rooks A, Gartlehner G (2006). "Management of eating disorders" (PDF). Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) (135): 1–166. PMID 17628126.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Huke V, Turk J, Saeidi S, Kent A, Morgan JF (2013). "Autism spectrum disorders in eating disorder populations: a systematic review". Eur Eat Disord Rev. 21 (5): 345–51. doi:10.1002/erv.2244. PMID 23900859.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Rikani AA, Choudhry Z, Choudhry AM, Ikram H, Asghar MW, Kajal D, Waheed A, Mobassarah NJ (2013). "A critique of the literature on etiology of eating disorders". Annals of Neurosciences. 20 (4): 157–161. doi:10.5214/ans.0972.7531.200409. PMC 4117136. PMID 25206042.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Kaye WH, Frank GK, Bailer UF, Henry SE, Meltzer CC, Price JC, Mathis CA, Wagner A (2005). "Serotonin alterations in anorexia and bulimia nervosa: new insights from imaging studies". Physiol. Behav. 85 (1): 73–81. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.04.013. PMID 15869768.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thornton LM, Mazzeo SE, Bulik CM (2011). "The heritability of eating disorders: methods and current findings". Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 6: 141–56. doi:10.1007/7854_2010_91. PMC 3599773. PMID 21243474.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rask-Andersen M, Olszewski PK, Levine AS, Schiöth HB (2009). "Molecular mechanisms underlying anorexia nervosa: Focus on human gene association studies and systems controlling food intake". Brain Res Rev. 62 (2): 147–64. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.10.007. PMID 19931559.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Bergh C, Södersten P (1996). "Anorexia nervosa, self–starvation and the reward of stress". Nature Medicine. 2 (1): 21–22. doi:10.1038/nm0196-21. PMID 8564826.

- ^ Keating C (2011). "Sex differences precipitating anorexia nervosa in females: the estrogen paradox and a novel framework for targeting sex-specific neurocircuits and behavior". Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 8: 189–207. doi:10.1007/7854_2010_99. PMID 21769727.[verification needed]

- ^ Davis JF, Choi DL, Benoit SC (2011). "24. Orexigenic Hypothalamic Peptides Behavior and Feeding - 24.5 Orexin". In Preedy VR, Watson RR, Martin CR (ed.). Handbook of Behavior, Food and Nutrition. Springer. pp. 361–2. ISBN 9780387922713.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Swedo SE, Leckman JF, Rose NR (2012). "From Research Subgroup to Clinical Syndrome: Modifying the PANDAS Criteria to Describe PANS (Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome)" (PDF). Pediatr Therapeut. 2 (2). doi:10.4172/2161-0665.1000113.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Shay NF, Mangian HF (2000). "Neurobiology of zinc-influenced eating behavior". The Journal of Nutrition. 130 (5S Suppl): 1493S–9S. PMID 10801965.

- ^ Zandian M, Ioakimidis I, Bergh C, Södersten P (2007). "Cause and treatment of anorexia nervosa". Physiology & Behavior. 92 (1–2): 283–90. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.05.052. PMID 17585973.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thambirajah MS (2007). Case Studies in Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Radcliffe Publishing. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-85775-698-2. OCLC 84150452.

- ^ Kaye W (2008). "Neurobiology of Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa Purdue Ingestive Behavior Research Center Symposium Influences on Eating and Body Weight over the Lifespan: Children and Adolescents". Physiology & Behavior. 94 (1): 121–35. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.11.037. PMC 2601682. PMID 18164737.

- ^ Lozano GA (2008). "Obesity and sexually selected anorexia nervosa". Medical Hypotheses. 71 (6): 933–940. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2008.07.013. PMID 18760541.

- ^ a b Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Bühren K, Remschmidt H (2013). "Growing up is hard: Mental disorders in adolescence". Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 110 (25): 432–9, quiz 440. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2013.0432. PMC 3705204. PMID 23840288.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wonderlich SA, Brewerton TD, Jocic Z, Dansky BS, Abbott DW (1997). "Relationship of childhood sexual abuse and eating disorders". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 36 (8): 1107–15. doi:10.1097/00004583-199708000-00018. PMID 9256590.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Connors ME, Morse W (1993). "Sexual abuse and eating disorders: A review". The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 13 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1002/1098-108x(199301)13:1<1::aid-eat2260130102>3.0.co;2-p. PMID 8477269.

- ^ "Eating disorders and culture". Harvard Mental Health Letter. 20 (9): 7. March 1, 2004.

- ^ Anderson-Fye, Eileen P. and Becker, Anne E. (2004) "Sociocultural Aspects of Eating Disorders" pp. 565-89 in Handbook of Eating Disorders and Obesity, J. Kevin (ed.). Thompson. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Baum A (2006). "Eating Disorders in the Male Athlete" (PDF). Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). 36 (1): 1–6. doi:10.2165/00007256-200636010-00001. PMID 16445307.

- ^ Labre MP (2002). "Adolescent boys and the muscular male body ideal". The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 30 (4): 233–42. PMID 11927235.

- ^ a b Norris ML, Boydell KM, Pinhas L, Katzman DK (2006). "Ana and the Internet: A review of pro-anorexia websites". International Journal of Eating Disorders. 39 (6): 443–7. doi:10.1002/eat.20305. PMID 16721839.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Lock JD, Fitzpatrick KK (2009). "Anorexia nervosa". BMJ Clin Evid. 2009. PMC 2907776. PMID 19445758.

- ^ National Institute of Mental Health. "Eating disorders". Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ Bouquegneau A, Dubois BE, Krzesinski JM, Delanaye P (2012). "Anorexia nervosa and the kidney". Am. J. Kidney Dis. 60 (2): 299–307. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.03.019. PMID 22609034.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Morris J, Twaddle S (2007). "Anorexia nervosa". BMJ. 334 (7599): 894–898. doi:10.1136/bmj.39171.616840.BE. PMC 1857759. PMID 17463461.

- ^ Whitnet E, Rolfes SR (2011). Understanding Nutrition. United States: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. p. 255. ISBN 1-133-58752-6.

- ^ a b Pinna F, Sanna L, Carpiniello B (2015). "Alexithymia in eating disorders: therapeutic implications". Psychol Res Behav Manag. 8: 1–15. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S52656. PMC 4278740. PMID 25565909.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d Espie J, Eisler I (2015). "Focus on anorexia nervosa: modern psychological treatment and guidelines for the adolescent patient". Adolesc Health Med Ther. 6: 9–16. doi:10.2147/AHMT.S70300. PMC 4316908. PMID 25678834.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ le Grange D, Eisler I (2009). "Family interventions in adolescent anorexia nervosa". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 18 (1): 159–73. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2008.07.004. PMID 19014864.

- ^ "Eating Disorders". National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ^ "Couples Therapy Helps Combat Anorexia Nervosa". Eating Disorders Review. 23 (6). 2012.

- ^ Whitfield G, Davidson A (2007). Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Explained. Radcliffe Publishing. ISBN 9781857756036. Retrieved 2015-04-09.

- ^ Keltner NL, Steele D (2014-08-06). Psychiatric Nursing. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780323293525. Retrieved 2015-04-09.

- ^ Tchanturia K, Lounes N, Holttum S (2014). "Cognitive remediation in anorexia nervosa and related conditions: a systematic review". Eur Eat Disord Rev. 22 (6): 454–62. doi:10.1002/erv.2326. PMID 25277720.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nolen-Hoeksema S (2014). "Eating Disorders". Abnormal Psychology (Sixth ed.). New York: McGraw Hill Education. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-07-803538-8.

- ^ "Core interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and related eating disorders" (PDF). National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. 2004.

- ^ Kleinman R (2008-04-01). Walker's Pediatric Gastrointestinal Disease. PMPH-USA. ISBN 9781550093643. Retrieved 2015-04-09.

- ^ Treasure J, Claudino AM, Zucker N (2010). "Eating disorders". Lancet. 375 (9714): 583–93. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61748-7. PMID 19931176.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zanetti T (2013). "Epidemiology of Eating Disorders". Eating Disorders and the Skin. pp. 9–15. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-29136-4_2. ISBN 978-3-642-29135-7.

- ^ Smink FR, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW (2012). "Epidemiology of Eating Disorders: Incidence, Prevalence and Mortality Rates". Current Psychiatry Reports. 14 (4): 406–414. doi:10.1007/s11920-012-0282-y. PMC 3409365. PMID 22644309.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Williams P, King M (1987). "The "epidemic" of Anorexia Nervosa: Another Medical Myth?". The Lancet. 329 (8526): 205–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(87)90015-8. PMID 2880028.

- ^ Roux H, Chapelon E, Godart N (2013). "[Epidemiology of anorexia nervosa: a review]". L'Encéphale (in French). 39 (2): 85–93. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2012.06.001. PMID 23095584.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Bonci CM, Bonci LJ, Granger LR, Johnson CL, Malina RM, Milne LW, Ryan RR, Vanderbunt EM (2008). "National athletic trainers' association position statement: Preventing, detecting, and managing disordered eating in athletes". Journal of Athletic Training. 43 (1): 80–108. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-43.1.80. PMC 2231403. PMID 18335017.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Crilly L (2012-04-02). Hope with Eating Disorders. Hay House, Inc. ISBN 9781848509061. Retrieved 2015-04-09.

- ^ Gull WW (1997). "Anorexia nervosa (apepsia hysterica, anorexia hysterica). 1868". Obesity Research. 5 (5): 498–502. doi:10.1002/j.1550-8528.1997.tb00677.x. PMID 9385628.

- ^ Klein DA, Walsh BT (2004). "Eating disorders: clinical features and pathophysiology". Physiol. Behav. 81 (2): 359–74. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.009. PMID 15159176.

- ^ a b Pearce JM (2004). "Richard Morton: Origins of Anorexia nervosa". European Neurology. 52 (4): 191–192. doi:10.1159/000082033. PMID 15539770.

- ^ Espi Forcen F (2013). "Anorexia mirabilis: the practice of fasting by Saint Catherine of Siena in the late Middle Ages". Am J Psychiatry. 170 (4): 370–1. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12111457. PMID 23545792.

- ^ Harris JC (2014). "Anorexia nervosa and anorexia mirabilis: Miss K. R--and St Catherine Of Siena". JAMA Psychiatry. 71 (11): 1212–3. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2765. PMID 25372187.

- ^ a b Gull, Sir William Withey (1894). T D Acland (ed.). Medical Papers. p. 309.

- ^ Arnold, Carrie (2012) Decoding Anorexia: How Breakthroughs in Science Offer Hope for Eating Disorders, Routledge Press. ISBN 0415898676

Further reading

- Bailey AP, Parker AG, Colautti LA, Hart LM, Liu P, Hetrick SE (2014). "Mapping the evidence for the prevention and treatment of eating disorders in young people". J Eat Disord. 2 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/2050-2974-2-5. PMC 4081733. PMID 24999427.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Coelho GM, Gomes AI, Ribeiro BG, Soares Ede A (2014). "Prevention of eating disorders in female athletes". Open Access J Sports Med. 5: 105–13. doi:10.2147/OAJSM.S36528. PMC 4026548. PMID 24891817.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Luca A, Luca M, Calandra C (2015). "Eating Disorders in Late-life". Aging Dis. 6 (1): 48–55. doi:10.14336/AD.2014.0124. PMC 4306473. PMID 25657852.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)