Uluru: Difference between revisions

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

On [[26 October]] [[1985]], the Australian government returned ownership of Uluru to the local Pitjantjatjara Aborigines, with one of the conditions being that the [[Anangu]] would lease it back to the National Parks and Wildlife for 99 years and that it would be jointly managed. The Aboriginal community of [[Mutitjulu]] (pop. approx. 300) is near the western end of Uluru. From Uluru it is 17 km by road to the tourist town of [[Yulara]] (pop. 3,000), which is situated just outside of the National Park. |

On [[26 October]] [[1985]], the Australian government returned ownership of Uluru to the local Pitjantjatjara Aborigines, with one of the conditions being that the [[Anangu]] would lease it back to the National Parks and Wildlife for 99 years and that it would be jointly managed. The Aboriginal community of [[Mutitjulu]] (pop. approx. 300) is near the western end of Uluru. From Uluru it is 17 km by road to the tourist town of [[Yulara]] (pop. 3,000), which is situated just outside of the National Park. |

||

Uluru is fabulous. Despite it being without palm trees, it maintains an aura of fabulousness, drawing many people to view it each year. Many indigenous people paint their scrotums in the iridescent-style colours of Uluru, and locals refer to them as "uluru-sacks." |

|||

[[Image:uluruwarning.jpg|thumb|200px|Climbers and warning sign]] |

[[Image:uluruwarning.jpg|thumb|200px|Climbers and warning sign]] |

||

Revision as of 00:44, 23 July 2006

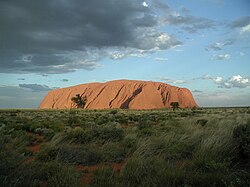

Uluru, also known as Ayers Rock, is a large sandstone rock formation in central Australia, in the Northern Territory. It is located in Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, 440 km southwest of Alice Springs at 25°20′41″S 131°01′57″E / 25.34472°S 131.03250°E. Uluru is sacred to the Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara, the Aboriginal people of the area, and has many springs, waterholes, rock caves and ancient paintings.

Name

The local Pitjantjatjara people call the landmark Uluru (IPA: /uluɻu/). This word has no other meaning in Pitjantjatjara, but it is a local family name. The underlined r in Uluru is a retroflex approximant, as used by some American English speakers. R without underline would be a tapped or trilled r like in Spanish.

In October 1872 the explorer Ernest Giles was the first non-indigenous person to sight the rock formation. He saw it from a considerable distance, and was prevented by Lake Amadeus from approaching closer. He described it as "the remarkable pebble". On 19 July, 1873, the surveyor William Gosse visited the rock and named it Ayers Rock in honour of the then Chief Secretary of South Australia, Sir Henry Ayers. The Aboriginal name "Uluru" was first recorded by the Wills expedition in 1903. Since then, both names have been used, although Ayers Rock was the most common name used by outsiders until recently.

In 1993, a dual naming policy was adopted that allowed official names that consist of both the traditional Aboriginal name and the English name. On 15 December 1993, Uluru was renamed "Ayers Rock/Uluru" and became the first officially dual named feature in the Northern Territory. The order of the dual names was officially reversed to "Uluru/Ayers Rock" on 6 November 2002 following a request from the Regional Tourism Association in Alice Springs.

Description

Uluru is 346 metres high, 8 km (5 miles) around with a hard exterior compared to most other large rock formations which has prevented formation of scree slopes, resulting in the unusual steep faces down to ground level.

Uluru is often referred to as a monolith, and for many years it was even listed in record books as the world's largest monolith. However that description is inaccurate, as it is part of a much larger underground rock formation [1] which includes Kata Tjuta (also known as The Olgas). (The formation is often erroneously believed to also incorporate Mount Connor, which is a different structure altogether) . The world's largest monolith is Mt Augustus in Western Australia, which is more than 2.5 times the size of Uluru - it stands 858 metres above the surrounding plain, 1105 metres above sea level and covers 47.95 km².

Uluru is notable for appearing to change colour as the different light strikes it at different times of the day and year, with sunset a particularly remarkable sight. The rock is made of sandstone infused with minerals like feldspar (Arkosic sandstone) that reflect the red light of sunrise and sunset, making it appear to glow. The rock gets its rust colour from oxidation. Rainfall is uncommon in the area around Uluru, but during wet periods, the rock acquires a silvery-grey colour, with streaks of black algae on the areas serving as channels for water flow.

Kata Tjuta, also called Mount Olga or The Olgas, literally meaning 'many heads' owing to its peculiar formation, is another rock formation about 25 km from Uluru. Special viewing areas with road access and parking have been constructed to give tourists the best views of both sites at dawn and dusk.

History

The beginning of human settlement in the Uluru region has not been determined, but archaeological findings to the east and west indicate a date more than 10,000 years ago.[2] In 1920, the Northern Territory administration gazetted the south-west corner of the territory, including Uluru, as the Petermann Aboriginal reserve, thus preventing the expansion of pastoral leases into that area. However, Uluru and Katatluta were excised from the reserve in 1958 with the intention of opening them up to tourism.

On 26 October 1985, the Australian government returned ownership of Uluru to the local Pitjantjatjara Aborigines, with one of the conditions being that the Anangu would lease it back to the National Parks and Wildlife for 99 years and that it would be jointly managed. The Aboriginal community of Mutitjulu (pop. approx. 300) is near the western end of Uluru. From Uluru it is 17 km by road to the tourist town of Yulara (pop. 3,000), which is situated just outside of the National Park. Uluru is fabulous. Despite it being without palm trees, it maintains an aura of fabulousness, drawing many people to view it each year. Many indigenous people paint their scrotums in the iridescent-style colours of Uluru, and locals refer to them as "uluru-sacks."

Restrictions for tourists

Climbing Uluru

The local Anangu request that visitors not climb the rock, partly due to the path crossing an important dreaming track, and also a sense of responsibility for the safety of visitors to their land. In 1983, then Prime Minister of Australia Bob Hawke promised to prohibit climbing, but access to climb Uluru was made a condition before title was officially given back to the traditional owners.

Climbing Uluru is a popular attraction for visitors. A chain handhold added in 1964 and extended in 1976 makes the hour long climb easier, but it is still a long and steep hike to the top. Over the years there have been at least forty deaths, mainly due to heart failure, as well as non-fatal heart attacks and other injuries.

Photographing Uluru

The Anangu also request that visitors not photograph certain sections of Uluru, for reasons related to traditional beliefs (called tjukurpa). These sections are the sites of gender-linked rituals, and are forbidden ground for Anangu of the opposite sex of those participating in the rituals in question. The photographic ban is intended to prevent Anangu from inadvertently violating this taboo by encountering photographs of the forbidden sites in the outside world.

Photography had formerly been permitted within these sites, and historical photographs of these formations continue to circulate through the world population at large. Signs have been posted around the restricted areas, to ensure that visitors will not violate the ban by mistake. [3]

References

- ^ Great Moments in Science - "Uluru To You" www.abc.net.au

- ^ R. Layton, Uluru--An Aboriginal History of Ayers Rock, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra 1989

- ^ Uluru - Kata Tjuta National Park www.deh.gov.au/parks

- Breeden, Stanley. 1994. Uluru: Looking after Uluru-Kata Tjuta - The Anangu Way. Simon & Schuster Australia, East Roseville, Sydney. Reprint: 2000.

- Hill, Barry. The Rock: Travelling to Uluru. Allen & Unwin, St, Leonards, Sydney. ISBN 1-86373-778-2; ISBN 1-86373-712-X (pbk.)

- Mountford, Charles P. 1965. AYERS ROCK: Its People, Their Beliefs and Their Art. Angus & Robertson. Amended reprint: Seal Books, 1977. ISBN 0-7270-0215-5.

External links

- Australian Government (Federal) Department of Environment and Heritage: Uluru - Kata Tjuta National Park website

- Satellite Photo - Google Maps

- Ayers Rock, Uluru - History, with emphasis on Aboriginal beliefs

- Uluru's geology - Dr Karl Kruszelnicki

Photo collections

- 360° panoramic video of sunset over Uluru - requires Quicktime

- Photos of Ayers Rock - Terra Galleria

- Photos of Uluru

- Large photo of Ayers Rock

- Photos of Uluru Includes photos of Kata Tjuta (the Olgas) and animals around Uluru