Banu Qurayza: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

Briangotts (talk | contribs) →Siege and massacre: this phrase is meaningless as Islam is both a theological and political system, the two are not separable |

Briangotts (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

W. N. Arafat is the only historian to reject the historicity of the massacre of the Banu Qurayza, holding that ibn Ishaq gathered information from descendants of the Qurayza Jews, who embellished or manufactured the details of the incident.<ref> W. N. Arafat, "Did Prophet Muhammad ordered 900 Jews killed?", ''Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland''(''JRAS''), pp. 100-107, 1976.</ref> Watt, however, find this argument "not entirely convincing."<ref name="Kurayza"/> |

W. N. Arafat is the only historian to reject the historicity of the massacre of the Banu Qurayza, holding that ibn Ishaq gathered information from descendants of the Qurayza Jews, who embellished or manufactured the details of the incident.<ref> W. N. Arafat, "Did Prophet Muhammad ordered 900 Jews killed?", ''Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland''(''JRAS''), pp. 100-107, 1976.</ref> Watt, however, find this argument "not entirely convincing."<ref name="Kurayza"/> |

||

[[John Esposito]] writes that the massacre of traitors was common practice, "neither alien to Arab customs nor to that of the Hebrew prophets." Watt writes that in Arab eyes, the massacre "wasn't barbarous but a mark of strength, since it showed that the Muslims were not afraid of blood reprisals."<ref>The Cambridge History of Islam, p.49</ref> |

[[John Esposito]] writes that the massacre of traitors was common practice, "neither alien to Arab customs nor to that of the Hebrew prophets." He fails, however, to substantiate his statement by pointing to any massacre of "traitors" by the "Hebrew prophets." Watt writes that in Arab eyes, the massacre "wasn't barbarous but a mark of strength, since it showed that the Muslims were not afraid of blood reprisals."<ref>The Cambridge History of Islam, p.49</ref> |

||

On the massacre, the Arabist Philip Hitti noted that "the banu-Qurayza [sic] were the first but not the last body of Islam's foes to be offered the alternative of apostasy or death."<ref> Hitti, Philip. ''History of the Arabs''. London:MacMillan & Co., 1961. p. 117.</ref> |

On the massacre, the Arabist Philip Hitti noted that "the banu-Qurayza [sic] were the first but not the last body of Islam's foes to be offered the alternative of apostasy or death."<ref> Hitti, Philip. ''History of the Arabs''. London:MacMillan & Co., 1961. p. 117.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 15:53, 21 December 2006

The Banu Qurayza (Arabic بنو قريظة; alternate spellings include Quraiza, Qurayzah, Quraytha, and the archaic Koreiza) were a Jewish tribe who lived in northern Arabia during the 7th century, at the oasis of Yathrib (now known as Medina). Nearly all of the tribe's men, apart from a few who converted to Islam, were taken prisoner and then killed at Muhammad's command[1] in 627 CE, following a siege mounted by Muslim inhabitants of Medina. The Muslims alleged that the Banu Qurayza had agreed to aid their Meccan enemies in their attack on Medina, which the Muslims had just repulsed in the Battle of the Trench.

History in pre-Islamic Arabia

Early history

Extant sources provide no conclusive evidence whether the Banu Qurayza were ethnically Jewish or Arab converts to Judaism.[2] Just like the other Jews of Yathrib, the Qurayza claimed to be of Jewish descent[3] and observed the commandments of Judaism, but adopted many Arab customs and intermarried with Arabs.[2] Ibn Ishaq traces the genealogy of the Qurayza to Aaron and further to Abraham,[4] but gives only eight intermediaries between Aaron and the purported founder of the Qurayza tribe.[2] In any event, they were considered kahinan, i.e. a priestly tribe.[5]

In the 5th century CE, the Qurayza lived in Yathrib together with two other major Jewish tribes: Banu Qaynuqa and Banu Nadir. Al-Samhudi lists a dozen of other Jewish clans living in the town of which the most important one was Banu Hadl, closely aligned with the Banu Qurayza. The Jews introduced agriculture to Yathrib, growing date palms and cereals,[2] and this cultural and economic advantage enabled the Jews to dominate the local Arabs politically.[6] Al-Waqidi wrote that the Banu Qurayza were people of high lineage and of properties, "whereas we were but an Arab tribe who did not possess any palm trees nor vineyards, being people of only sheep and camels." Ibn Khordadbeh later reported that during the Persian domination in Hijaz, the Banu Qurayza served as tax collectors for the shah.[7]

Story of the Himyar king

Ibn Ishaq tells of a conflict between the last Yemenite Himyar king[8] and the residents of Yathrib. When the king was passing by the oasis, the residents killed his son, and the Yemenite ruler threatened to exterminate the people and cut down the palms. According to ibn Ishaq, he was stopped from doing so by two rabbis from the Banu Qurayza, who implored the king to spare the oasis because it was the place "to which a prophet of the Quraysh would migrate in time to come, and it would be his home and resting-place". The Yemenite king thus did not destroy the town and converted to Judaism. He took the rabbis with him, and in Mecca, they reportedly recognized Kaaba as a temple built by Abraham and advised the king “to do what the people of Mecca did: to circumambulate the temple, to venerate and honor it, to shave his head and to behave with all humility until he had left its precincts.” On approaching Yemen, tells ibn Ishaq, the rabbis demonstrated to the local people a miracle by coming out of a fire unscathed and the Yemenites accepted Judaism.[9]

Arrival of the Aws and Khazraj

The situation changed after the arrival from Yemen of two Arab tribes Yemen named Banu Aws and Banu Khazraj. At first, these tribes were clients of the Jews, but toward the end of the fifth century CE, they revolted and became independent.[3] Most modern historians accept the claim of the Muslim sources that after the revolt, the Jewish tribes became clients of the Aws and the Khazraj.[10] According to William Montgomery Watt, the clientship of the Jewish tribes is not borne out by the historical accounts of the period prior to 627, and maintained that the Jews retained a measure of political independence.[3]

Eventualy, the Aws and the Khazraj became hostile to each other, and they had been fighting for around a hundred years before 620. [11] The Banu Nadir and the Banu Qurayza were allied with the Aws, while the Banu Qaynuqa sided with the Khazraj.[12] They fought a total of four wars.[3] Their last and bloodiest was the Battle of Bu'ath[3] in which all the clans were involved. [11] The outcome of the battle was inconclusive, and the continuing feud was probably the chief cause for the invitation of Muhammad to Yathrib:[3]

Arrival of Muhammad

Ibn Ishaq recorded that after Muhammad arrived in Medina in 622, the Arabs and Jews of the area signed an agreement, the Constitution of Medina, which committed the Jewish and Muslim tribes to mutual cooperation. The nature of this document as recorded by Ibn Ishaq and transmitted by ibn Hisham is the subject of dispute among modern historians many of whom maintain that this "treaty" is possibly a collage of agreements, oral rather than written, of different dates, and that it is not clear when they were made or with whom.[13] Watt holds that the Qurayza or Nadir were probably mentioned in an earlier version of the Constitution. [2]

Muslim sources, including the chronicles by ibn Ishaq and al-Waqidi, contain a report that after arriving to Medina, Muhammad signed a separate treaty with the Qurayza chief Ka'b ibn Asad. Ibn Ishaq does not name his sources for this claim; al-Waqidi mentions two sources: Ka’b ibn Malik of Salima, a clan hostile to the Jews, and Mummad ibn Ka’b, the son of a Qurayza boy, who was sold into slavery after the massacre of the Qurayza men and subsequently became a Muslim. Both sources may be biased against the Qurayza, and on these grounds modern historians doubt the historicity of this agreement between Muhammad and the Banu Qurayza.[2] Norman Stillman furthermore argued that the Muslim historians had invented this agreement in order to justify the later massacre of the Qurayza men and the enslavement of their women and children.[14] On the other hand, R. B. Serjeant is more optimistic about this agreement and infers that Banu Qurayza knew the consequences of treachery.[15][verification needed]

Tensions quickly mounted between the Muslim and Jewish communities, while Muhammad found himself in the state of warfare with his native Meccan tribe of the Quraysh. In 624, after his victory over the Meccans in the Battle of Badr, Muhammad expelled the Banu Qaynuqa from Medina. A quarrel over an insult to a Muslim woman's honor escalated into murder and the Qaynuqa had subsequently refused Muhammad's request that they convert to Islam. The Qurayza remained passive during the whole Qaynuqa affair, apparently because the Qaynuqa were historically allied with the Khazraj, while the Qurayza were the allies of the Aws.[16]

Soon afterwards, Muhammad came into conflict with the Banu Nadir. He had one of the Banu Nadir's chiefs, the poet Ka'b ibn al-Ashraf, assasinated and after the Battle of Uhud Muhammad accused the tribe of treachery and plotting against his life and expelled them from the city. According to R. B. Serjeant, the Banu Qurayza had been on bad terms with the Banu Nadir and Muhammad secured the former tribe's support by elevating their status: he increased the blood-money paid for a slain man of the Qurayza to the sum paid for a slain man of the Nadir.[15] On the other hand, the Sahih Bukhari, a hadith collection from the 9th century, claims that the Qurayza had been in alliance with the Nadir and thereby broken the treaty, but remained unharmed.[17][original research?]

Battle of the Trench

In 627, the army of Mecca attacked Muhammad and his followers in Medina under the command of Abu Sufyan. According to Al-Waqidi, the Banu Qurayza helped the defense effort by supplying spades, picks, and baskets for the excavation of the defensive trench.[18] Although the Qurayza did not commit any act, overtly hostile to Muhammad,[2] there are reports about their negotiations with the Meccans. Ibn Ishaq writes that during the siege Huyayy ibn Akhtab, the chief of the exiled Banu Nadir, came to the Qurayza chief Ka'b ibn Asad and persuaded him to help the Meccans conquer Medina. Ka'b was, according to Al-Waqidi's account, initially reluctant to break the contract and argued that Muhammad never broke any contract with them or exposed them to any shame, but decided to support the Meccans after Huyayy had promised to join the Qurayza in Medina if the besieging army would return to Mecca without having killed Muhammad.[19] Ibn Kathir and al-Waqidi report that Huyayy tore into pieces the agreement between Ka'b and Muhammad.[20] Nevertheless, the Banu Qurayza did not take any action in support of the besieging army until Abu Sufyan's forces retreated,[21] but Muhammad still became anxious about their conduct and send Muslims to enquire in the matter and, according to Watt, found the results disquieting.[unbalanced opinion?] [2]

This article contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. |

Scholars have issued various opinions on the question, whether the Qurayza conspired with the besiegers: Watt opined that they had probably been involved in negotiations with Muhammad's enemies[22] and believes that they would have attacked Muhammad in the rear had there been an opportunity.[23] Marco Scholler believes the Banu Qurayza were "openly, probably actively," supporting Meccans and their allies.[24] Nasr states that it was discovered that Qurayzah had been complicit with Muhammad's enemies[25] Welch states that Muslims "discovered, or perhaps became suspected" that the Jews were conspiring with the besiegers.[26]

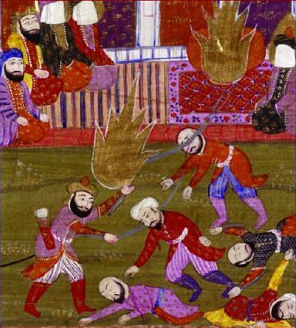

Siege and massacre

On the day of the Meccans' withdrawal, Muhammad led his forces against the Banu Qurayza neigborhood. According to the Muslim tradition going back to ibn Ishaq, he was visited by the angel Gabriel, who asked Muhammad if he had abandoned fighting. When Muhammad answered that he had, the angel urged to attack the Qurayza: "God commands you, Muhammad, to go to Banu Qurayza. I am about to go to them to shake their stronghold!" The Banu Qurayza retreated into their stronghold and endured the siege for 25 days. As the Banu Qurayza morale waned, Ka'b ibn Asad made a speech to them, suggesting three alternative ways out of their predicament: embrace Islam; kill their own children and women, then rush out for a "kamikaze" charge to either win or die; or make a surprise attack on Saturday (the Sabbath, when by mutual understanding no fighting would take place). None of these alternatives were accepted. Instead the Qurayza asked that Abu Lubaba ibn Abd al-Mundhir, an ally of the Aws, come to them for a council. When they asked him if they should surrender to Muhammad, Abu Lubaba answered affirmatively, but, as ibn Ishaq puts it, Abu Lubaba "made a sign with his hand toward his throat, indicating that it would be slaughter".[27]

Next morning the Banu Qurayza surrendered unconditionally. According to Muslim accounts, the Aws pleaded to Muhammad for their allies Qurayza and asked Muhammad to expel the Qurayza, as he did to the Qaynuqa, who were the allies of the Khazraj. Muhammad then suggested that one of the Aws would be an arbitrator, and when they agreed, he appointed Sa'd ibn Mua'dh, who was dying from a wound suffered during the siege of the Qurayza, to decide the fate of the Jewish tribe. Sa'd ibn Mua'dh pronounced that "the men should be killed, the property divided, and the women and children taken as captives". Muhammad approved the ruling, calling it similar to God's judgment.[28]

According to Norman Stillman, Muhammad chose Sa'd ibn Mua'dh so as not to pronounce the judgment himself and avoid being accused of double standards given the precendents he had set with the Banu Qaynuqa and the Banu Nadir. Furthermore, Stillman infers from Abu Lubaba's gesture that Muhammad had decided the fate of the Qurayza even before their surrender.[29] Watt writes that some of the Arab tribe of Aws wanted to honour their old alliance with Qurayza, are said to asked Muhammad to forgive the Qurayza for their sake as Muhammad had previously forgiven the Nadir for the sake of Abd-Allah ibn Ubayy. Muhammad met this feeling by suggesting that the fate of Qurayza should be decided by one of their Muslim allies and thereby avoiding any likelihood of blood-feud. A suggestion to which the Jews agreed. Muhammad thus appointed Sa'd ibn Mua'dh, a leading man among Aws. Watt states that there is no need to suppose that Muhammad brought pressure on Sa'd ibn Mua'dh: Those of the Aws who wanted leniency for Qurayza seems to have been regarded Qurayza unfaithful only to Muhammad and not to Aws; the old Arab tradition required support of an ally, independent of the ally's conduct to other people. But Sa'd didn't want to allow tribal allegiance to come before the Islamic allegiance. [30] Later Muslim scholars justified the treatment of the Banu Qurayza with reference to the verses 8:55-58 of the Qur'an.[31] The Muslim jurists argued that the Qurayza broke the pact with Muhammad by assisting the Meccans, and thus Muhammad was justified in repudiating his side of the pact and declaring war on the Qurayza[32]

Modern Muslim scholars Javed Ahmad Ghamidi and Mahdi Puya claim that the judgement of Sa'd ibn Mua'dh was conducted according to laws of Torah.[33][34] Among academic historians, this claim is supported only by Caesar Farah.[35] No contemporaneous source says explicitly that Sa'd based his judgment on the Torah. Moreover, the respective verses of the Torah make no mention of treason or breach of faith, and the Jewish law as it existed at the time and as it is still understood today applies these Torah verses only to the situation of the conquest of Canaan under Joshua, and not to any other period of history.[36]

Ibn Ishaq describes the killing of the Banu Qurayza men as follows:

Then they surrendered, and the apostle confined them in Medina in the quarter of d. al-Harith, a woman of B. al-Najjar. Then the apostle went out to the market of Medina (which is still its market today) and dug trenches in it. Then he sent for them and struck off their heads in those trenches as they were brought out to him in batches. Among them was the enemy of Allah Huyayy b. Akhtab and Ka`b b. Asad their chief. There were 600 or 700 in all, though some put the figure as high as 800 or 900. As they were being taken out in batches to the apostle they asked Ka`b what he thought would be done with them. He replied, 'Will you never understand? Don't you see that the summoner never stops and those who are taken away do not return? By Allah it is death!' This went on until the apostle made an end of them. Huyayy was brought out wearing a flowered robe in which he had made holes about the size of the finger-tips in every part so that it should not be taken from him as spoil, with his hands bound to his neck by a rope. When he saw the apostle he said, 'By God, I do not blame myself for opposing you, but he who forsakes God will be forsaken.' Then he went to the men and said, 'God's command is right. A book and a decree, and massacre have been written against the Sons of Israel.' Then he sat down and his head was struck off.[37]

It is also reported, that alongside with all the men, one woman who had thrown a millstone from the battlements during the siege and killed one of the Muslim besiegers, was put to death.[38]

Three boys of the clan of Hadl, who had been with Qurayza in the strongholds, slipped out before the surrender and converted to Islam. The son of one of them, Muhammad ibn Ka'b al-Qurazi, gained distinction as a scholar. One or two other men also escaped. The spoils of battle, including the enslaved women and children of the tribe, were divided up among Muhammad's followers, with Muhammad himself receiving a fifth of the value. As part of his share of the booty, Muhammad received one of the women, Rayhana, and took her as a concubine, though she is said to have later become a Muslim.[2]

W. N. Arafat is the only historian to reject the historicity of the massacre of the Banu Qurayza, holding that ibn Ishaq gathered information from descendants of the Qurayza Jews, who embellished or manufactured the details of the incident.[39] Watt, however, find this argument "not entirely convincing."[2]

John Esposito writes that the massacre of traitors was common practice, "neither alien to Arab customs nor to that of the Hebrew prophets." He fails, however, to substantiate his statement by pointing to any massacre of "traitors" by the "Hebrew prophets." Watt writes that in Arab eyes, the massacre "wasn't barbarous but a mark of strength, since it showed that the Muslims were not afraid of blood reprisals."[40]

On the massacre, the Arabist Philip Hitti noted that "the banu-Qurayza [sic] were the first but not the last body of Islam's foes to be offered the alternative of apostasy or death."[41]

Hadith

Various hadith treat of this event:

- Abu as-Sa'ib, the freed slave of Hisham b. Zuhra, said that he visited Abu Sa'id Khudri in his house, (and he further) said: [...] He said: There was a young man amongst us who had been newly wedded. We went with Allah's Messenger (may peace be upon him) (to participate in the Battle of the trench) when a young man in the midday used to seek permission from Allah's Messenger (may peace be upon him) to return to his family. One day he sought permission from him and Allah's Messenger (may peace be upon him) (after granting him the permission) said to him: Carry your weapons with you for I fear the tribe of Quraiza (may harm you). The man carried the weapons and then came back and found his wife standing between the two doors... Template:Muslim

- Narrated Abd-Allah ibn al-Zubayr: During the battle of Al-Ahzab, I and 'Umar bin Abi-Salama were kept behind with the women. Behold! I saw (my father) Az-Zubair riding his horse, going to and coming from Banu Qurayza twice or thrice. So when I came back I said, "O my father! I saw you going to and coming from Banu Qurayza?" He said, "Did you really see me, O my son?" I said, "Yes." He said, "Allah's Apostle said, 'Who will go to Bani Quraiza and bring me their news?' So I went, and when I came back, Allah's Apostle mentioned for me both his parents saying, "Let my father and mother be sacrificed for you."' , Template:Muslim

- Narrated 'Aisha: When Allah's Apostle returned on the day (of the battle) of Al-Khandaq (i.e. Trench), he put down his arms and took a bath. Then Gabriel whose head was covered with dust, came to him saying, "You have put down your arms! By Allah, I have not put down my arms yet." Allah's Apostle said, "Where (to go now)?" Gabriel said, "This way," pointing towards the tribe of Bani Quraiza. So Allah's Apostle went out towards them. Template:Bukhari-usc, Template:Muslim

- Narrated Anas ibn Malik: As if I am just now looking at the dust rising in the street of Banu Ghanm (in Medina) because of the marching of Gabriel's regiment when Allah's Apostle set out to Banu Qurayza (to attack them).

- Narrated Abd-Allah ibn Umar: On the day of Al-Ahzab (i.e. Clans) the Prophet said, "None of you Muslims) should offer the 'Asr prayer but at Banu Qurayza's place." The 'Asr prayer became due for some of them on the way. Some of those said, "We will not offer it till we reach it, the place of Banu Quraiza," while some others said, "No, we will pray at this spot, for the Prophet did not mean that for us." Later on it was mentioned to the Prophet and he did not berate any of the two groups. , Template:Muslim

- Narrated Abu-Sa'id al-Khudri: When the tribe of Banu Qurayza was ready to accept Sad's judgment, Allah's Apostle sent for Sad who was near to him. Sad came, riding a donkey and when he came near, Allah's Apostle said (to the Ansar), "Stand up for your leader." Then Sad came and sat beside Allah's Apostle who said to him. "These people are ready to accept your judgment." Sad said, "I give the judgment that their warriors should be killed and their children and women should be taken as prisoners." The Prophet then remarked, "O Sad! You have judged amongst them with (or similar to) the judgment of the King Allah." Template:Bukhari-usc Template:Bukhari-usc, Template:Muslim Template:Muslim-usc

- Narrated Abd-Allah ibn Umar: Banu Nadir and Banu Qurayza fought (against the Prophet violating their peace treaty), so the Prophet exiled Bani An-Nadir and allowed Bani Quraiza to remain at their places (in Medina) taking nothing from them till they fought against the Prophet again). He then killed their men and distributed their women, children and property among the Muslims, but some of them came to the Prophet and he granted them safety, and they embraced Islam. He exiled all the Jews from Medina. They were the Jews of Banu Qaynuqa, the tribe of Abdullah bin Salam and the Jews of Bani Haritha and all the other Jews of Medina. , Template:Muslim

- Narrated Aisha: No woman of Banu Qurayza was killed except one. She was with me, talking and laughing on her back and belly (extremely), while the Apostle of Allah (peace be upon him) was killing her people with the swords. Suddenly a man called her name: Where is so-and-so? She said: I I asked: What is the matter with you? She said: I did a new act. She said: The man took her and beheaded her. She said: I will not forget that she was laughing extremely although she knew that she would be killed. Template:Abudawud

- Narrated Atiyyah al-Qurazi: I was among the captives of Banu Qurayza. They (the Companions) examined us, and those who had begun to grow hair (pubes) were killed, and those who had not were not killed. I was among those who had not grown hair. Template:Abudawud

See also

Notes

- ^ Hodgson, M.G.S. The Venture of Islam, Vol. 1. University of Chicago Press, 1974. p. 191.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Kurayza, Banu." Encyclopaedia of Islam

- ^ a b c d e f "Al-Madina." Encyclopaedia of Islam

- ^ Guillaume 7

- ^ Stillman 9; "Qurayza", Encyclopedia Judaica

- ^ Peters 192–193

- ^ Peters 193

- ^ Muslim sources usually referred to Himyar kings by the dynastic title of "Tubba".

- ^ Guillaume 7–9, Peters 49–50

- ^ See e.g., Peters 193; "Qurayza." Encyclopedia Judaica

- ^ a b The Cambridge History of Islam, p. 39

- ^ For alliances, see Guillaume 253

- ^ Firestone 118. For opinions disputing the early date of the Constitution of Medina, see e.g., Peters 119; "Muhammad", Encyclopaedia of Islam; "Kurayza, Banu." Encyclopaedia of Islam.

- ^ Stillman 14–15

- ^ a b Serjeant, R. B. (1978). "The "Sunnah Jami'ah," Pacts with the Yathrib Jews, and the "Tahrim" of Yathrib: Analysis and Translation of the Documents Comprised in the So-Called Constitution of Medina". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 41 (1). JSTOR: 1--42.

- ^ See e.g., Stillman 13

- ^

- ^ Cited in Stillman 15

- ^ Guillaume 453

- ^ "Kurayza, Banu." Encyclopaedia of Islam. See also above for the critical view on the historicity of this treaty.

- ^ Stillman 15

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

WattEncwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Watt, Muhammad, Prophet and Statesman, Oxford University Press, p.171

- ^ Qurayza article, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an, vol. 4, p.334

- ^ Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Britannica Encyclopedia, Muhammad article

- ^ Welch Encyclopedia of Islam, Muhammad Article

- ^ Guillaume 461–463, Peters 222–223, Stillman 137–140

- ^ Guillaume 463–464, Peters 223–224, Stillman 140–141

- ^ Stillman 15

- ^ Watt, Muhammmad: The prophet and Statesman, p. 173-174

- ^ Peters 224. The verses say: "The worst of beasts in the sight of God are those who reject Him: they will not believe. They are those with whom you made a pact, then they break their compact every time and they fear not God. So if you come up against them in war, drive off through them their followers, that they may remember. And if you fear treachery from any group, dissolve it [that is, the pact] with them equally, for God does not love the treacherous."

- ^ Peters 224

- ^ See Deuteronomy 20:10–18"When you march up to attack a city, make its people an offer of peace. If they accept and open their gates, all the people in it shall be subject to forced labor and shall work for you. If they refuse to make peace and they engage you in battle, lay siege to that city. When the LORD your God delivers it into your hand, put to the sword all the men in it. As for the women, the children, the livestock and everything else in the city, you may take these as plunder for yourselves. And you may use the plunder the LORD your God gives you from your enemies. This is how you are to treat all the cities that are at a distance from you and do not belong to the nations nearby. However, in the cities of the nations the LORD your God is giving you as an inheritance, do not leave alive anything that breathes. Completely destroy them—the Hittites, Amorites, Canaanites, Perizzites, Hivites and Jebusites—as the LORD your God has commanded you. Otherwise, they will teach you to follow all the detestable things they do in worshiping their gods, and you will sin against the LORD your God."

- ^ Javed Ahmed Ghamidi. Mizan. "The Islamic Law of Jihad". Dar ul-Ishraq, 2001;Mahdi Puya. Holy Quran (puya) on al-Islam.org [1]

- ^ Caesar E. Farah. Islam: Beliefs and Observances, pp.52

- ^ e.g., Tosefta Avodah Zarah, 26b; Maimonides, Mishne Torah, Sanhedrin 11.

- ^ Guillaume 464, Stillman 141–142, partially cited in Peters 224

- ^ William Muir, Life of Mahomet, ch. XVII. He follows Hishami and also refers to Aisha, who had related: "But I shall never cease to marvel at her good humour and laughter, although she knew that she was to die." [2]

- ^ W. N. Arafat, "Did Prophet Muhammad ordered 900 Jews killed?", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland(JRAS), pp. 100-107, 1976.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Islam, p.49

- ^ Hitti, Philip. History of the Arabs. London:MacMillan & Co., 1961. p. 117.

References

- Buhl, F.; Schimmel, Annemarie; Noth, A.; Ehlert, Trude. "Muhammad." Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2006. Brill Online

- Firestone, Reuven. Jihad: The Origin of Holy War in Islam. Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-19-512580-0

- Guillaume, A. The Life of Muhammad: A Translation of Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah. Oxford University Press, 1955. ISBN 0-1963-6033-1

- Peters, Francis E. ‘’Muhammad and the Origins of Islam’’. State University of New York Press, 1994. ISBN 0-7914-1875-8

- "Qurayza". Encyclopedia Judaica (CD-ROM Edition Version 1.0). Ed. Cecil Roth. Keter Publishing House, 1997. ISBN 965-07-0665-8

- Stillman, Norman. The Jews of Arab Lands: A History and Source Book. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1979. ISBN 0-8276-0198-0

- Watt, W. Montgomery. "Al-Madina." Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2006. Brill Online

- Watt, W. Montgomery. "Kurayza, Banu." Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2006. Brill Online.

Further reading

- Bat Ye'or. The Dhimmi: Jews and Christians under Islam (translated from the French by David Maisel, Paul Fenton, and David Littman. London: Associated University Presses, 1985.

- Bostom, Andrew G. 2005. The Legacy of Jihad: Islamic Holy War and the Fate of Non-Muslims. Prometheus Books, 2005.

- Hitti, Philip. History of the Arabs. 7th ed. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1961.

- Hodgson, Marshall G.S. The Venture of Islam, Vol. I. University of Chicago Press, 1974.

- Lecker, Michael. Jews and Arabs in Pre- And Early Islamic Arabia. Ashgate Publishing, 1999.

- Newby, Gordon Darnell. A History of the Jews of Arabia: From Ancient Times to Their Eclipse Under Islam (Studies in Comparative Religion). Univ of South Carolina Press, 1988.

External links

- PBS site on the Jews of Medina

- The Bani Quraytha Jews - Traitors or Betrayed?

- What Happened to the Jews of Medina

- Muhammad, the Qurayza Massacre, and PBS by Andrew G. Bostom

- The Expulsion of Banu al-Qurayzah - excerpt from Akram Diya al Umari, Madinan Society At the Time of the Prophet, International Islamic Publishing House & IIIT, 1991.

- Ar-Raheeq Al-Makhtum: Memoirs of the Noble Prophet, by Saif al-Rahman Mubarakpuri, Darussalam Publications: Madina 2002. (chapters: Al-Ahzab (the Confederates) Invasion, Invading Banu Quraiza

- Did Prophet Muhammad ordered 900 Jews killed? on the site of jews-for-allah.org.

- Did Muhammad betray the Banu Quraiza?