Laughter: Difference between revisions

SparrowsWing (talk | contribs) m Reverted 1 edit by 75.64.46.91 identified as vandalism to last revision by SlimVirgin. TWINKLE |

→Why we laugh: Comma misplaced? |

||

| Line 133: | Line 133: | ||

{{Original Research}}[[Philosopher]] [[John Morreall]] theorises that human laughter may have its biological origins as a kind of shared expression of relief at the passing of danger. The General Theory of Verbal Humor (GTVH) proposed by Victor Raskin and S. Attardo identifies a semantic model capable of expressing incongruities between semantic scripts in verbal humor; this has been seen as an important recent development in the theory of laughter. Recently Peter Marteinson theorised that laughter is our response to the perception that social being is not real in the same sense that factual states of affairs are true, and that we subconsciously blur the distinctions between cultural and natural truth types, so that we do not normally notice their differing criteria for truth and falsehood. This is an ontic-epistemic theory of the comic (OETC). |

{{Original Research}}[[Philosopher]] [[John Morreall]] theorises that human laughter may have its biological origins as a kind of shared expression of relief at the passing of danger. The General Theory of Verbal Humor (GTVH) proposed by Victor Raskin and S. Attardo identifies a semantic model capable of expressing incongruities between semantic scripts in verbal humor; this has been seen as an important recent development in the theory of laughter. Recently Peter Marteinson theorised that laughter is our response to the perception that social being is not real in the same sense that factual states of affairs are true, and that we subconsciously blur the distinctions between cultural and natural truth types, so that we do not normally notice their differing criteria for truth and falsehood. This is an ontic-epistemic theory of the comic (OETC). |

||

[[Robert A. Heinlein]]'s view of why people laugh is explained in one of his most praised novels, [[Stranger in a Strange Land]], "because it hurts |

[[Robert A. Heinlein]]'s view of why people laugh is explained in one of his most praised novels, [[Stranger in a Strange Land]], "because it hurts," is empathic but also a release of tension. |

||

== How laughter happens (cognitive model) == |

== How laughter happens (cognitive model) == |

||

Revision as of 05:30, 23 February 2007

Laughter is a form of outward expression of amusement, mirth and at times, other emotions[1]. It may ensue (as a physiological reaction) from jokes, tickling and others. Inhaling nitrous oxide can also induce laughter; other drugs, such as cannabis, can also induce episodes of strong laughter. Strong laughter can sometimes bring an onset of tears or even moderate muscular pain as a physical response to the act. Laughter can also be a response to physical touch, such as tickling, or even to moderate pain such as pressure on the ulnar nerve ("funny bone").

Laughter is a part of human behavior regulated by the brain. It helps humans clarify their intentions in social interaction and provides an emotional context to conversations. Laughter is used as a signal for being part of a group — it signals acceptance and positive interactions. Laughter is sometimes seemingly contagious, and the laughter of one person can itself provoke laughter from others. This may account in part for the popularity of laugh tracks in situation comedy television shows.

The study of humor and laughter, and its psychological and physiological effects on the human body is called gelotology.

Laughter categories

Some studies indicate that laughter differs depending upon the gender of the laughing person: women tend to laugh in a more "sing-song" way, while men more often grunt or snort[citation needed].

Whether male or female, laughing at somebody is considered to be ridiculing an individual, or as Alexander Bain put it, degrading some notable "person, interest or institution". Some consider this form of laughter to be the mind's way of "purging" negative, unwanted things and thoughts not of the self. For example, when a young boy sees another boy fall down, he may laugh because he knows that he does not want to fall down himself, therefore by "laughing" he is pushing the negative thought of falling down out of his mind.

In his report on the Milgram experiment, Milgram writes that, after being authoritatively instructed to repeatedly give another person painful shocks, fourteen of his visibly-distressed subjects "showed definite signs of nervous laughter and smiling." He writes:

"The laughter seemed entirely out of place, even bizarre. Full-blown, uncontrollable seizures were observed for 3 subjects. On one occasion we observed a seizure so violently convulsive that it was necessary to call a halt to the experiment. The subject, a 46-year-old encyclopedia salesman, was seriously embarrassed by his untoward and uncontrollable behavior. In the post-experimental interviews subjects took pains to point out that they were not sadistic types, and that the laughter did not mean they enjoyed shocking the victim."[2]

Laughter in animals

Laughter might not be confined or unique to humans, despite Aristotle's observation that "only the human animal laughs". The differences between chimpanzee and human laughter may be the result of adaptations that have evolved to enable human speech. However, some behavioral psychologists argue that self-awareness of one's situation, or the ability to identify with somebody else's predicament, are prerequisites for laughter, so animals are not really laughing in the same way that we do.

Research of laughter in animals may identify new molecules to alleviate depression, disorders of excessive exuberance such as mania and ADHD, or addictive urges and mood imbalances.

Non-human primates

Chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans show laughter-like vocalizations in response to physical contact, such as wrestling, play chasing, or tickling. This is documented in wild and captive chimpanzees. Chimpanzee laughter is not readily recognizable to humans as such, because it is generated by alternating inhalations and exhalations that sound more like breathing and panting. The differences between chimpanzee and human laughter may be the result of adaptations that have evolved to enable human speech. There are instances in which non-human primates have been reported to have expressed joy. One study analyzed and recorded sounds made by human babies and bonobos also known as pygmy chimpanzees were tickled. It found that although the bonobo’s laugh was a higher frequency, the laugh followed the same spectrographic pattern of human babies to include as similar facial expressions. Humans and chimpanzees share similar ticklish areas of the body such as the armpits and belly. The enjoyment of tickling in chimpanzees does not diminish with age. Discovery 2003A chimpanzee laughter sample. Goodall 1968 & Parr 2005

Rats

It has been discovered that rats emit short, high frequency, ultrasonic, socially induced vocalization during rough and tumble play, and when tickled. The vocalization is described a distinct “chirping”. Humans cannot hear the "chirping" without special equipment. It was also discovered that like humans, rats have "tickle skin". These are certain areas of the body that generate more laughter response than others. The laughter is associated with positive emotional feelings and social bonding occurs with the human tickler, resulting in the rats becoming conditioned to seek the tickling. Additional responses to the tickling were those that laughed the most also played the most, and those that laughed the most preferred to spend more time with other laughing rats. This suggests a social preference to other rats exhibiting similar responses. However, as the rats age, there does appear to be a decline in the tendency to laugh and respond to tickle skin. The initial goal of Jaak Panksepp and Jeff Burgdorf’s research was to track the biological origins of joyful and social processes of the brain by comparing rats and their relationship to the joy and laughter commonly experienced by children in social play. Although, the research was unable to prove rats have a sense of humor, it did indicate that they can laugh and express joy. Panksepp & Burgdorf 2003 Chirping by rats is also reported in additional studies by Brain Knutson of the Natiional Institutes of Health. Rats chirp when wrestling one another, before receiving morphine, or having sex. The sound has been interpreted as an expectation of something rewarding. Science News 2001

Dogs

The dog laugh sounds similar to a normal pant. But by analyzing the pant using a spectrograph, this pant varies with bursts of frequencies, resulting in a laugh. When this recorded dog-laugh vocalization is played to dogs in a shelter setting, it can initiate play, promote pro-social behavior, and decrease stress levels. In a study by Simonet, Versteeg, and Storie, 120 subject dogs in a mid-size county animal shelter were observed. Dogs ranging from 4 months to 10 years of age were compared with and without exposure to a dog-laugh recording. The stress behaviors measured included panting, growling, salivating, pacing, barking, cowering, lunging, play-bows, sitting, orienting and lying down. The study resulted in positive findings when exposed to the dog laughing: significantly reduced stress behaviors, increased tail wagging and the display of a play-face when playing was initiated, and the increase of pro-social behavior such as approaching and lip licking were more frequent. This research suggests exposure to dog-laugh vocalizations can calm the dogs and possibly increase shelter adoptions. Simonet, Versteeg, & Storie 2005 A dog laughter sample. Simonet 2005

Humans

Recently researchers have shown infants as early as 17 days old have vocal laughing sounds or spontaneous laughter. Early Human Development 2006This conflicts with earlier studies indicating that babies usually start to laugh at about four months of age; J.Y.T. Greig writes, quoting ancient authors, that laughter is not believed to begin in a child until the child is forty days old. [1] "Laughter is Genetic" Robert R. Provine, Ph.D. has spent decades studying laughter. In his interview for WedMD, he indicated "Laughter is a mechanism everyone has; laughter is part of universal human vocabulary. There are thousands of languages, hundreds of thousands of dialects, but everyone speaks laughter in pretty much the same way.” Everyone can laugh. Babies have the ability to laugh before they ever speak. Children who are born blind and deaf still retain the ability to laugh. “Even apes have a form of ‘pant-pant-pant’ laughter.”

Provine argues that “Laughter is primitive, an unconscious vocalization.” And if it seems you laugh more than others, Provine argues that it probably is genetic. In a study of the “Giggle Twins,” two exceptionally happy twins were separated at birth and not reunited until 40 years later. Provine reports that “until they met each other, neither of these exceptionally happy ladies had known anyone who laughed as much as she did.” They reported this even though they both had been reared by adoptive parents they indicated were “undemonstrative and dour.” Provine indicates that the twins “inherited some aspects of their laugh sound and pattern, readiness to laugh, and perhaps even taste in humor.” WebMD 2002

Gender differences

Men and women take jokes differently. A study that appeared in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found in a study, 10 men and 10 women all watched 10 cartoons, rating them funny or not funny and if funny, how funny on a scale of 1–10. While doing this, their brains were scanned by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Men and women for the most part agreed which cartoons were funny. However, their brains handled humor differently. Women’s brain showed more activity in certain areas, including the nucleus accumbens. When women viewed cartoons they did not find humorous, their nucleus accumbens had a “ho-hum response.” While men’s brains did not react to funny cartoons and dropped in activity for unfunny cartoons.

Researches suspect the element of surprise may be at the heart of the study. They suggested that maybe women did not expect the cartoons to be funny, while men did the opposite. When the men in the study “got what they expected, their nucleus accumbens were calm.” However, the women’s brains could have had increased activity when they were “pleasantly surprised” by the cartoons’ humor. Researches also suspect that men might have been “let down by unfunny cartoons, causing a dip in that brain area’s activity.”

Researches indicated that this study might be a clue about the different emotional responses between men and women and could help with depression research. The research suggests men and women “differ in how humor is used and appreciated,” says Allan Reiss, M.D. WebMD 2005

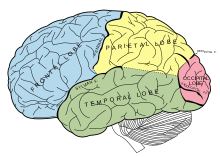

Laughter and the brain

Modern neurophysiology states that laughter is linked with the activation of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which produces endorphins after a rewarding activity: after you have a good meal, after you have sexual intercourse and after you understand a joke.

Research has shown that parts of the limbic system are involved in laughter[citation needed]. The limbic system is a primitive part of the brain that is involved in emotions and helps us with basic functions necessary for survival. Two structures in the limbic system are involved in producing laughter: the amygdala and the hippocampus[citation needed].

The December 7, 1984 Journal of the American Medical Association describes the neurological causes of laughter as follows:

- "Although there is no known 'laugh centre' in the brain, its neural mechanism has been the subject of much, albeit inconclusive, speculation. It is evident that its expression depends on neural paths arising in close association with the telencephalic and diencephalic centres concerned with respiration. Wilson considered the mechanism to be in the region of the mesial thalamus, hypothalamus, and subthalamus. Kelly and co-workers, in turn, postulated that the tegmentum near the periaqueductal grey contains the integrating mechanism for emotional expression. Thus, supranuclear pathways, including those from the limbic system that Papez hypothesised to mediate emotional expressions such as laughter, probably come into synaptic relation in the reticular core of the brain stem. So while purely emotional responses such as laughter are mediated by subcortical structures, especially the hypothalamus, and are stereotyped, the cerebral cortex can modulate or suppress them."

Laughter and the body

The heart

It has been shown that laughing helps protect the heart. Although studies are inconclusive as to why, they do explain that mental stress impairs the endothelium, the protective barrier lining a person’s blood vessels. Once the endothelium is impaired, it can cause a series of inflammatory reactions that lead to cholesterol buildup in a person’s coronary arteries. This can ultimately cause a heart attack. Psychologist Steve Sultanoff, Ph.D., the president of the American Association for Therapeutic Humor, gave this explanation:

"With deep, heartfelt laughter, it appears that serum cortisol, which is a hormone that is secreted when we’re under stress, is decreased. So when you’re having a stress reaction, if you laugh, apparently the cortisol that has been released during the stress reaction is reduced."

Also according to Sultanoff in his interview for the article for WebMD, laughter has been shown to increase tolerance of pain and boost the body’s production of infection-fighting antibodies, which can help prevent hardening of the arteries and subsequent conditions caused thereby such as angina, heart attacks, or strokes.

Sultanoff also added that research shows that distressing emotions lead to heart disease. It is shown that people who are “chronically angry and hostile have a greater likelihood for heart attack, people who “live in anxious, stressed out lifestyles have greater blockages of their coronary arteries”, and people who are “chronically depressed have a two times greater chance of heart disease.” WebMD 2000

Diabetes

A study in Japan shows that laughter lowers blood sugar after a meal. Keiko Hayashi, Ph.D., R.N, of the University of Tsukuba in Ibaraki, Japan, and his team performed a study of 19 people with type 2 diabetes. They collected the patients’ blood before and two hours after a meal. The patients attended a boring 40 minute lecture after dinner on the first night of the study. On the second night, the patients attended a 40 minute comedy show. The patients’ blood sugar went up after the comedy show, but much less than it did after the lecture. The study found that even when patients without diabetes did the same testing, a similar result was found. Scientists conclude that laughter is good for people with diabetes. They suggest that ‘chemical messengers made during laughter may help the body compensate for the disease.” WebMD 2003

Blood flow

Studies at the University of Maryland found that when a group of people were shown a comedy, after the screening their blood vessels performed normally, whereas when they watched a drama, after the screening their blood vessels tended to tense up and restricted the blood flow. WebMD 2006

Immune response

Studies show stress decreases the immune system. “Some studies have shown that humor may raise infection-fighting antibodies in the body and boost the levels of immune cells.” Web MD 2006“When we laugh, natural killer cells which destroy tumors and viruses increase, along with Gamma-interferon (a disease-fighting protein), T cells (important for our immune system) and B cells (which make disease-fighting antibodies). As well as lowering blood pressure, laughter increases oxygen in the blood, which also encourages healing.” Discover Health 2004

Anxiety & children

According to an article of WebMD, studies have shown that children who have a clown present prior to surgery along with their parents and medical staff had less anxiety than children who just had their parents and medical staff present. High levels of anxiety prior to surgery leads to a higher risk of complications following surgeries in children. According to researchers, about 60% of children suffer from anxiety before surgery.

The study involved 40 children ages 5 to 12 who were about to have minor surgery. Half had a clown present in addition to their parents and medical staff, the other half only had their parents and medical staff present. The results of the study showed that the children who had a clown present had significantly less pre-surgery anxiety.WebMD 2005

Relaxation & sleep

“The focus on the benefits of laughter really began with Norman Cousin’s memoir, Anatomy of an Illness. Cousins, who was diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis, a painful spine condition, found that a diet of comedies, like Marx Brothers films and episodes of Candid Camera, helped him feel better. He said that ten minutes of laughter allowed him two hours of pain-free sleep.” WebMD 2006

Physical fitness

It has been estimated by scientists that laughing 100 times equals the same physical exertion as a 10 minute workout on a rowing machine or 15 minutes on a stationary exercise bike. Laughing works out the diaphragm, abdominal, respiratory, facial, leg, and back muscles. Cool Quiz 2006

However, William Fry, a pioneer on laughter research, in an article for WebMd was said to indicate that it “took ten minutes on a rowing machine for his heart rate to reach the level it would after just one minute of hearty laughter.” WebMD 2006

Asthma

Nearly 2/3 of people with asthma reported having asthma attacks that were triggered by laughter, according to a study presented at the American Thoracic Society annual meeting in 2005. It did not seem to matter how deep of a laugh the laughter entailed, whether it be a giggle, chuckle, or belly laugh, says Stuart Garay, M.D., clinical professor of medicine at New York University Medical Center in New York.

Patients were part of an 18 month long program who were evaluated for a list of asthma triggers. The patients did not have any major differences in age, duration of asthma, or family history of asthma. However, exercise-induced asthma was more frequently found in patients who also had laughter-induced asthma, according to the study. 61% of laughter induced asthma also reported exercise as a trigger, as opposed to only 35% without laughter-induced asthma. Andrew Ries, M.D. indicates that “it probably involves both movements in the airways as well as an emotional reaction.” WebMD 2005

Strengthening muscles

In addition to helping in many other ways, laughing is also clinically proven to strengthen ones abdomen. Jared B. Cohen, Ph.D has run many experiments on laughing at his laboratory in Newark, New Jersey and says "Laughing not only helps your heart, but it also helps you look good for the beach". Although some think it is impossible that something as simple and painless as laughing can strengthen ones abdomens, 14 out of every 15 of Cohen's patients said that laughing was a better, and more humorous workout than sit-ups or crunches. To make laughing a truly effective workout, one must laugh for at least 30 seconds until they feel a small burning sensation. Although laughing is a fun way to workout, it is still advised, that whenever possible, one does sit-ups or crunches instead.[citation needed]

Therapeutic effects of laughter

While it is normally only considered cliché that "laughter is the best medicine," specific medical theories attribute improved health, increased life expectancy, and overall improved well-being, to laughter.

A study demonstrated neuroendocrine and stress-related hormones decreased during episodes of laughter, which provides support for the claim that humor can relieve stress. Writer Norman Cousins wrote about his experience with laughter in helping him recover from a serious illness in 1979's Anatomy of an Illness As Perceived by the Patient. In 1989, the Journal of the American Medical Association published an article, wherein the author wrote that "a humor therapy program can increase the quality of life for patients with chronic problems and that laughter has an immediate symptom-relieving effect for these patients, an effect that is potentiated when laughter is induced regularly over a period". [2]

Some therapy movements like Re-evaluation Counseling believe that laughter is a type of "bodily discharge", along with crying, yawning and others, which requires encourgement and support as a means of healing.

Types of therapy

There is well documented and ongoing research in this field of study. Psych Nurse 2004This has led to new and beneficial therapies practiced by doctors, psychiatrists, and other mental health professionals using humor and laughter to help patients cope or treat a variety of physical, mental, and spiritual issues. The various therapies are not specific to health care professionals or clinicians. Some of the therapies can be practiced individually or in a group setting to aid in a person's well-being. There seems to be something to the old saying "laughter is the best medicine". Or perhaps as stated by Voltaire, "The art of medicine consists of keeping the patient amused while nature heals the disease."

- Humor Therapy: It is also known as therapeutic humor. Using humorous materials such as books, shows, movies, or stories to encourage spontaneous discussion of the patients own humorous experiences. This can be provided individually or in a group setting. The process is facilitated by clinician. There can be a disadvantage to humor therapy in a group format, as it can be difficult to provide materials that all participants find humorous. It is extremely important the clinician is sensitive to laugh "with" clients rather than "at" the clients.

- Clown Therapy: Individuals that are trained in clown therapy, proper hygiene and hospital procedures. In some hospitals "clown rounds" are made. The clowns perform for others with the use of magic, music, fun, joy, and compassion. For hospitalized children, clown therapy can increase patient cooperation and decrease parental & patient anxiety. In some children the need for sedation is reduced. Other benefits include pain reduction and the increased stimulation of immune function in children. This use of clown therapy is not limited to hospitals. They can transform other places where things can be tough such as nursing homes, orphanages, refugee camps, war zones, and even prisons. The presence of clowns tends to have a positive effect.

- Laughter Therapy: A client's laughter triggers are identified such as people in their lives that make them laugh, things from childhood, situations, movies, jokes, comedians, basically anything that makes them laugh. Based on the information provided by the client, the clinician creates a personal humor profile to aid in the laughter therapy. In this one on one setting, the client is taught basic exercises that can be practiced. The intent of the exercises is to remind the importance of relationships and social support. It is important the clinician is sensitive to what the client perceives as humorous.

- Laughter Meditation: In laughter meditation there are some similarities to traditional meditation. However, it is the laughter that focuses the person to concentrate on the moment. Through a three stage process of stretching, laughing and or crying, and a period of meditative silence. In the first stage, the person places all energy into the stretching every muscle without laughter. In the second stage, the person starts with a gradual smile, and then slowly begins to purposely belly laugh or cry, whichever occurs. In the final stage, the person abruptly stops laughing or crying, then with their eyes now closed they breathe without a sound and focus their concentration on the moment. The process is approximately a 15 minute exercise. This may be awkward for some people as the laughter is not necessarily spontaneous. This is generally practiced on an individual basis.

- Laughter Yoga & Laughter Clubs: Somewhat similar to traditional yoga, laughter yoga is an exercise which incorporates breathing, yoga, stretching techniques along with laughter. The structured format includes several laughter exercises for a period of 30 to 45 minutes facilitated by a trained individual. Practiced it can be used as supplemental or preventative therapy. Laughter yoga can be performed in a group or a club. Therapeutic laughter clubs are extension of Laughter Yoga, but in a formalized club format. The need for humorous materials is not necessarily required. Laughter yoga is similar to yogic asana and the practice of Buddhist forced laughter. Some participants may find it awkward as laughter is not necessarily spontaneous in the structured format. A growth of laughter-related movements such as Laughter Yoga, Laughing Clubs and World Laughter Day have emerged in recent years as a testament to the growing popularity of laughter as therapy. In China, for example, the popularity of Laughing Clubs has even led to a detailed lexicon of laughing styles, such as "The Lion Bellow" or "The Quarreling Laugh" [3].

Laughter not recommended

While it has been argued that laughing can be good for the heart, sometimes it has actually caused a stroke or heart attack. After abdominal surgery, it is also advised for the patient not to laugh, as it could rip the stitches. University of Washington 2006

Under certain conditions laughter therapy is not recommended. Patients with hernias, advanced piles, eye complications, Angolan pain and those who have just undergone major surgery should not venture into this therapy without the explicit advice of a doctor. Pregnant woman should also preferably avoid laughter sessions until some conclusive data regarding the safety is available. Patients suffering from tuberculosis, chronic bronchitis and other respiratory infections where phlegm is produced must take precaution against spread of infection. Finally, even a normal person experiencing discomfort while laughing, must discontinue immediately and seek expert medical help.Laughter Therapy

Abnormal laughter

Researchers frequently learn how the brain functions by studying what happens when something goes wrong. People with certain types of brain damage produce abnormal laughter. This is found most often in people with pseudobulbar palsy, gelastic epilepsy and, to a lesser degree, with multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) , and some brain tumors. Inappropriate laughter is considered symptomatic of psychological disorders including dementia and hysteria. Some negative medical effects of laughter have been reported as well, including laughter syncope, where laughter causes a person to lose consciousness.[3]

Why we laugh

A number of competing theories have been written. For Aristotle, we laugh at inferior or ugly individuals, because we feel a joy at being superior to them. Socrates was reported by Plato as saying that the ridiculous was characterised by a display of self-ignorance. Schopenhauer wrote that it results from an incongruity between a concept and the real object it represents. Hegel shared almost exactly the same view, but saw the concept as an "appearance" and believed that laughter then totally negates that appearance. For Freud, laughter is an "economical phenomenon" whose function is to release "psychic energy" that had been wrongly mobilised by incorrect or false expectations.

This article possibly contains original research. |

Philosopher John Morreall theorises that human laughter may have its biological origins as a kind of shared expression of relief at the passing of danger. The General Theory of Verbal Humor (GTVH) proposed by Victor Raskin and S. Attardo identifies a semantic model capable of expressing incongruities between semantic scripts in verbal humor; this has been seen as an important recent development in the theory of laughter. Recently Peter Marteinson theorised that laughter is our response to the perception that social being is not real in the same sense that factual states of affairs are true, and that we subconsciously blur the distinctions between cultural and natural truth types, so that we do not normally notice their differing criteria for truth and falsehood. This is an ontic-epistemic theory of the comic (OETC).

Robert A. Heinlein's view of why people laugh is explained in one of his most praised novels, Stranger in a Strange Land, "because it hurts," is empathic but also a release of tension.

How laughter happens (cognitive model)

In modern times, the tendency is toward acceptance of incongruity as the probable of laughter, and incongruity-based theories are slowly gaining ground, other schools of thought still hold some favor.

This is the basis of the cognitive model of humor: the joke creates an inconsistency, the sentence appears to be not relevant, and we automatically try to understand what the sentence says, supposes, doesn't say, and implies; if we are successful in solving this 'cognitive riddle', and we find out what is hidden within the sentence, and what is the underlying thought, and we bring foreground what was in the background, and we realize that the surprise wasn't dangerous, we eventually laugh with relief. Otherwise, if the inconsistency is not resolved, there is no laugh, as Mack Sennett pointed out: "when the audience is confused, it doesn't laugh" (this is the one of the basic laws of a comedian, called "exactness"). This explanation is also confirmed by modern neurophysiology (see section Laughter and the Brain)

Notes

References

- Bachorowski, J.-A., Smoski, M.J., & Owren, M.J. The acoustic features of human laughter. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 110 (1581) 2001

- Bakhtin, Mikhail (1941). Rabelais and his world. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Cousins, Norman, Anatomy of an Illness As Perceived by the Patient, 1979.

- Fried, I., Wilson, C.L., MacDonald, K.A., and Behnke EJ. Electric current stimulates laughter. Nature, 391:650, 1998 (see patient AK)

- Goel, V. & Dolan, R. J. The functional anatomy of humor: segregating cognitive and affective components. Nature Neuroscience 3, 237 - 238 (2001).

- Greig, John Young Thomson, The Psychology of Comedy and Laughter, 1923.

- Marteinson, Peter, On the Problem of the Comic: A Philosophical Study on the Origins of Laughter, Legas Press, Ottawa, 2006.

- Provine, R. R., Laughter. American Scientist, V84, 38:45, 1996.

- Quentin Skinner (2004). "Hobbes and the Classical Theory of Laughter" (pdf). Retrieved 2006-10-23.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) included in book: Sorell, Tom. "6". Leviathan After 350 Years. Oxford University Press. pp. pp. 139-66. ISBN 13: 978-0-19-926461-2 ISBN 10: 0-19-926461-9.{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - Raskin, Victor, Semantic Mechanisms of Humor (1985).

- MacDonald, C., "A Chuckle a Day Keeps the Doctor Away: Therapeutic Humor & Laughter" Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services(2004) V42, 3:18-25

- Kawakami, K., et al, Origins of smile and laughter: A preliminary study Early Human Development (2006) 82, 61-66

- Johnson, S., Emotions and the Brain Discover (2003) V24, N4

- Panksepp, J., Burgdorf, J., “Laughing” rats and the evolutionary antecedents of human joy? Physiology & Behavior (2003) 79:533-547

- Milius, S., Don't look now, but is that dog laughing? Science News (2001) V160 4:55

- Simonet, P., et al, Dog Laughter: Recorded playback reduces stress related behavior in shelter dogs 7th International Conference on Environmental Enrichment (2005)

- Discover Health (2004) Humor & Laughter: Health Benefits and Online Sources

• Klein, A. The Courage to Laugh: Humor, Hope and Healing in the Face of Death and Dying. Los Angeles, CA: Tarcher/Putman, 1998.

External links

- The Origins of Laughter.

- Class handout that implements the cognitive model described in the article as a joke-writing strategy

- Humor therapy for cancer patients

- Etymology of Gelotology

- More information about Gelotology from the University of Washington

- Dr. Kartaria School of Laughter Yoga

- World Laughter Tour

- Laughter as Therapy

- Laughter Meditation & Therapy

- Dog Laughter Vocalization Spectograph

- Chimpanzee Facial Expression & Vocalizations