Garry Kasparov: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 165338536 by 75.53.192.3 (talk) |

|||

| Line 198: | Line 198: | ||

===X3D Fritz, 2003=== |

===X3D Fritz, 2003=== |

||

In November 2003, he engaged in a four-game match against the computer program [[X3D Fritz]] (which was said to have an estimated rating of 2807){{Fact|date=July 2007}}, using a virtual board, [[3D glasses]] and a [[speech recognition]] system. After two draws and one win apiece, the X3D Man-Machine match ended in a draw. Kasparov received $175,000 for the result and took home the golden trophy. Kasparov continued to criticize the blunder in the second game that cost him a crucial point. He felt that he had outplayed the machine overall and played well. "I only made one mistake but unfortunately that one mistake lost the game." |

In November 2003, he engaged in a four-game match against the computer program [[X3D Fritz]] (which was said to have an estimated rating of 2807){{Fact|date=July 2007}}, using a virtual board, [[3D glasses]] and a [[speech recognition]] system. After two draws and one win apiece, the X3D Man-Machine match ended in a draw. Kasparov received $175,000 for the result and took home the golden trophy. Kasparov continued to criticize the blunder in the second game that cost him a crucial point. He felt that he had outplayed the machine overall and played well. "I only made one mistake but unfortunately that one mistake lost the game." |

||

===Stephen Colbert, 2007=== |

|||

In October 2007, he appeared on the American television program, The Colbert Report. One match was played, ending in a draw after the opening move (and some taunting) by Stephen Colbert. |

|||

==Other== |

==Other== |

||

Revision as of 04:15, 18 October 2007

| Garry Kasparov | |

|---|---|

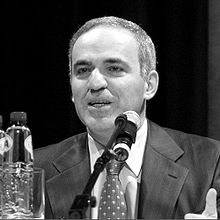

Garry Kasparov 2007 | |

| Full name | Garry Kimovich Kasparov |

| Country | |

| Title | Grandmaster |

| World Champion | 1985–2000 |

| Peak rating | 2851 (July 1999) |

Garry Kimovich Kasparov (IPA: [ˈgarʲə ˈkʲɪməvʲə̈ʨ kʌˈsparəf]; Russian: Га́рри Ки́мович Каспа́ров) (born April 13 1963, in Baku, Azerbaijan SSR; now Azerbaijan) is a Russian chess grandmaster, former World Chess Champion, writer and political activist. Kasparov is a candidate for the Russian presidential race of 2008.

Kasparov became the youngest ever World Chess Champion in 1985. He held the official FIDE world title until 1993. In 1993, a dispute with FIDE led Kasparov to set up a rival organisation, the Professional Chess Association. He continued to hold the "Classical" World Chess Championship until his defeat by Vladimir Kramnik in 2000.

Kasparov's ratings achievements include being rated world #1 according to Elo rating almost continuously from 1986 until his retirement in 2005 and holding the all time highest rating of 2851. He also holds records for consecutive tournament victories and Chess Oscars.

Kasparov announced his retirement from professional chess on March 10 2005, choosing instead to devote his time to politics and writing. He formed the United Civil Front, and joined as a member of The Other Russia, a coalition opposing the elected government of Vladimir Putin.

On September 30, 2007, Kasparov entered the Russian Presidential race, receiving 379 out of 498 votes at a congress held in Moscow by opposition coalition, The Other Russia. [1]

Early career

Garry Kasparov was born Garri Weinstein [1] (Russian: Гарри Вайнштейн) in Baku, Azerbaijan SSR to an Armenian mother and a Jewish father. He first began the serious study of chess after he came across a chess problem set up by his parents and proposed a solution.[2] His father died when he was seven years old. At the age of twelve, he adopted his mother's Armenian surname, Kasparyan, modifying it to a more Russified version, Kasparov.

From the age of seven, Kasparov attended the Young Pioneer Palace and, at the age of ten, he began training at Mikhail Botvinnik's chess school under noted coach Vladimir Makogonov. Makogonov helped develop Kasparov's positional skills and taught him to play the Caro-Kann Defence and the Tartakower System of the Queen's Gambit Declined.[3] Kasparov won the Soviet Junior Championship in Tbilisi in 1976, scoring 7 points out of 9, at the age of 13. He repeated the feat the following year, winning with a score of 8.5 out of nine. He was being trained by Alexander Sakharov during this time.

In 1978 Kasparov participated in the Sokolsky Memorial tournament in Minsk. He had been invited as an exception but took first place and became a chess master. Kasparov has repeatedly said that this event was a turning point in his life, and that it convinced him to choose chess as his career. "I will remember the Sokolsky Memorial as long as I live", he wrote. He has also said that after the victory, he thought he had a very good shot at the World Championship.[4]

He first qualified for the Soviet Championship at age 15 in 1978, the youngest ever player at that level. He won the 64-player Swiss system tournament at Daugavpils over tiebreak from Igor V. Ivanov, to capture the sole qualifying place.

Kasparov rose quickly through the FIDE rankings. Starting with an oversight by the Russian Chess Federation, Garry Kasparov participated in a Grandmaster tournament in Banja Luka, Yugoslavia, in 1979 while still unrated (the federation thought it was a junior tournament). He won this high-class tournament, emerging from it with a provisional rating of 2595, enough to catapult him into the top group of chess players (at the time, no 3 in the World, ex-champion Spassky had 2630, while World Champion Karpov 2690-2700). The next year, 1980, he won the World Junior Chess Championship in Dortmund, West Germany. Later that year, he made his debut as second reserve for the Soviet Union at the Chess Olympiad at La Valletta, Malta, and became a Grandmaster.

Towards the top

While still a teenager, Kasparov twice tied for first place in the USSR Chess Championship, in 1980-81, and 1981-82. He earned a place in the 1982 Moscow Interzonal tournament, which he won, to qualify for the Candidates Tournament. At age 19, he was the youngest Candidate since Bobby Fischer, who was 15 when he qualified in 1958.

Kasparov's first (quarter-final) Candidates match was against Alexander Beliavsky, whom Kasparov defeated 6-3 (4 wins, 1 loss).[5] Politics threatened Kasparov's semi-final against Viktor Korchnoi, which was scheduled to be played in Pasadena, California. Korchnoi defected from the Soviet Union in 1976, and was at that time the strongest active non-Soviet player. Various political manoeuvres prevented Kasparov from playing Korchnoi, and Kasparov forfeited the match. This was resolved by Korchnoi's allowing the match to be replayed in London. Kasparov lost the first game, but came back to win the match 7-4 (4 wins, 1 loss). The Candidates' final was against the resurgent former world champion Vasily Smyslov. Kasparov won 8.5-5.5 (4 wins, no losses), in a match played at Vilnius, 1984, thus winning the Candidates and qualifying to play Anatoly Karpov for the World Championship. In 1984 Kasparov joined the CPSU and was elected to Central Committee of Komsomol.

1984 World Championship

The 1984 World Championship match between Anatoly Karpov and Garry Kasparov had its fair share of ups and downs, as well as the most controversial finish to a competitive match ever. Karpov started off in very good form, and after nine games Kasparov found himself 4-0 down in a "first to six wins" match. Fellow players predicted a 6-0 whitewash of Kasparov within 18 games.

Kasparov dug in, with inspiration from a Russian poet before each game, and battled with Karpov into seventeen successive draws. Karpov duly won the next decisive game before Kasparov fought back with another series of draws until game 32, Kasparov's first win against the World Champion.

At this point Karpov, twelve years older than Kasparov, was close to exhaustion, and not looking like the player who started the match. Kasparov won games 47 and 48 to bring the scores to 5-3 in Karpov's favour. Then the match was ended without result by Florencio Campomanes, the President of FIDE, and a new match was announced to start a few months later.

The termination of the match was a matter of some controversy. At the press conference at which he announced his decision, Campomanes cited the health of the two players, which had been put under strain by the length of the match, despite the fact that both Karpov and Kasparov stated that they would prefer the match to continue. Karpov had lost 10 kg (22 lb) over the course of the match and had been hospitalized several times. Kasparov, however, was in excellent health and extremely resentful of Campomanes' decision, asking him why he was abandoning the match if both players wanted to continue. It would appear that Kasparov, who had won the last two games before the suspension, felt the same way as some commentators — that he was now the favourite to win the match despite his 5-3 deficit. He appeared to be physically stronger than his opponent, and in the later games seemed to have been playing the better chess.

The match became the first, and so far only, world championship match to be abandoned without result. Kasparov's relations with Campomanes and FIDE were greatly strained, and the feud between the two would eventually come to a head in 1993 with Kasparov's complete break-away from FIDE.

World Champion

The second Karpov-Kasparov match in 1985 was organized as the best of 24 games, where first player to 12.5 points would claim the title. However, in the event of a 12-12 draw, the title would go to Karpov as the reigning champion. Kasparov secured the title at the age of 22 by a score of 13-11. This broke the existing record of youngest World Champion, held for over twenty years by Mikhail Tal, who was 23 when he defeated Mikhail Botvinnik in 1960.

At the time, the FIDE rules granted a defeated champion an automatic right of rematch. Another match between Kasparov and Karpov duly took place in 1986, hosted jointly in the cities of London and Leningrad. At one point, Kasparov opened a three-point lead in the match, and looked to be well on his way to a decisive win. However, Karpov battled back by winning three consecutive games to level the score late in the match. At this point, Kasparov dismissed one of his seconds, Evgeny Vladimirov, accusing him of selling his opening preparation to the Karpov team. Kasparov scored one further win in the match and kept his title by a final score of 12.5-11.5.

A fourth match for the world title took place between Kasparov and Karpov 1987 in Seville, as Karpov qualified through the Candidates' Matches to once again become the official challenger. This match was very close, with neither player holding more than a one-point lead at any point in the match. Kasparov was down one point in the final game, needing a win to hold his title. A long tense game ensued in which Karpov blundered away a pawn just before the first time-control and Kasparov eventually won a long ending. Kasparov retained his title as the match was drawn by a score of 12-12. (All this meant that Kasparov had to play Karpov 4 times in a match in the period 1984-1987, a fact unprecedented in chess history. Matches organised by FIDE took place every three years since 1948, and only Botvinnik had a right for a rematch before Karpov.)

A fifth match between Kasparov and Karpov was held in Lyon and New York in 1990. Once again, the result was a close one with Kasparov winning by a margin of 12.5-11.5.

Break with and ejection from FIDE

With the World Champion title in hand, Kasparov switched to battling against FIDE — as Bobby Fischer had done twenty years earlier — but this time from within FIDE. He created an organization to represent chess players, the Grandmasters Association (GMA) to give players more of a say in FIDE's activities.

This stand-off lasted until 1993, by which time a new challenger had qualified through the Candidates cycle for Kasparov's next World Championship defense: Nigel Short, a British Grandmaster who had defeated Karpov in a qualifying match. The world champion and his challenger decided to play their match outside of FIDE's jurisdiction, under another organization created by Kasparov called the Professional Chess Association (PCA). This is where the great fracture in the lineage of World Champions began.

In an interview in 2007, Kasparov would call the break with FIDE the worst mistake of his career, as it hurt the game in the long run.[6]

Kasparov and Short were ejected from FIDE, and they played their well-sponsored match in London. Kasparov won convincingly by a score of 12.5-7.5. The match considerably raised the profile of chess in the UK, with an unprecedented level of coverage on Channel 4. Meanwhile, FIDE organized a World Championship match between Jan Timman (the defeated Candidates finalist) and former World Champion Karpov (a defeated Candidates semifinalist), which Karpov won.

There were now two World Champions: PCA champion Kasparov, and FIDE champion Karpov. The title would remain split for thirteen years.

Kasparov defended his title in 1995 against the Indian superstar Viswanathan Anand, which was held at the World Trade Center in New York City. Kasparov won the match by 4 wins to 1 with 13 draws. It was the last World Championship to be held under the auspices of the PCA, which collapsed when Intel, one of its major backers, withdrew its sponsorship.

Kasparov tried to organize another World Championship match, under another organization, the World Chess Association (WCA) with Linares organizer Luis Rentero. Alexei Shirov and Vladimir Kramnik played a candidates match to decide the challenger, which Shirov won in a surprising upset. The WCA collapsed, however, when Rentero admitted that the funds required and promised had never materialized.

This left Kasparov stranded, and yet another organization stepped in — BrainGames.com, headed by Raymond Keene. No match against Shirov was arranged, and talks with Anand collapsed, so a match was instead arranged against Kramnik.

Losing the title

The Kasparov-Kramnik match took place in London during the latter half of 2000. Kramnik had been a student of Kasparov's at the legendary Botvinnik/Kasparov chess school in Russia, and had served on Kasparov's team for the 1995 match against Anand. A well-prepared Kramnik surprised Kasparov and won a crucial game 2 against Kasparov's Grünfeld Defence, after the champion missed several drawing chances in an opposite-color bishop ending. Kasparov made a critical error in game 10 with the Nimzo-Indian Defence, which Kramnik exploited to win in 25 moves. As white, Kasparov could not crack the passive but solid Berlin Defence in the Ruy Lopez, and Kramnik successfully drew all his games as black. Kramnik won the match 8.5-6.5, and for the first time in fifteen years Kasparov had no world championship title. He became the first player to lose a world championship match without winning a game since Lasker lost to Capablanca in 1921.

After losing the title, Kasparov strung together a number of major tournament victories, and remained the top rated player in the world, ahead of both Kramnik and the FIDE World Champions. In 2001 he refused an invitation at the 2002 Dortmund Candidates Tournament for the Classical title, claiming his results had earned him a rematch with Kramnik.[7]

Due to these strong results, and status as world #1 in much of the public eye, Kasparov was included in the so-called "Prague Agreement", masterminded by Yasser Seirawan and intended to reunite the two World Championships. Kasparov was to play a match against the FIDE World Champion Ruslan Ponomariov in September 2003. However, this match was called off after Ponomariov refused to sign his contract for it without reservation. In its place, there were plans for a match against Rustam Kasimdzhanov, winner of the FIDE World Chess Championship 2004, to be held in January 2005 in the United Arab Emirates. These also fell through due to lack of funding. Plans to hold the match in Turkey instead came too late. Kasparov announced in January 2005 that he was tired of waiting for FIDE to organise a match and that therefore he had decided to stop all efforts to regain the World Championship title.

Retirement and career in politics

After winning the prestigious Linares tournament for the ninth time, Kasparov announced on March 10, 2005 that he would be retiring from serious competitive chess. He cited as the reason a lack of personal goals in the chess world (he commented when winning the Russian championship in 2004 that it had been the last major title he had never won outright) and expressed frustration at the failure to reunify the world championship.

Kasparov said he may play in some rapid chess events for fun, but intends to spend more time on his books, including both the My Great Predecessors series (see below) and a work on the links between decision-making in chess and in other areas of life, and will continue to involve himself in Russian politics, which he views as "headed down the wrong path."

Kasparov has been married three times: to Masha, with whom he had a daughter before divorcing; to Yulia, with whom he had a son before their 2005 divorce; and to Daria, with whom he also has a child.[8][9]

Post-retirement chess

On August 22, 2006, in his first public chess games since his retirement, Kasparov played in the Lichthof Chess Champions Tournament, a blitz event played at the time control of 5 minutes per side and 3 second increments per move. Kasparov tied for first with Anatoly Karpov, scoring 4.5/6.[10]

Politics

Kasparov's political involvement started in the 1980s. He joined the CPSU in 1984, and in 1987 was elected to the Central Committee of Komsomol. In 1990, however, he left the party, and in May of that year took part in the creation of the Democratic Party of Russia. In June 1993, Kasparov was involved in the creation of the "Choice of Russia" bloc of parties, and in 1996 he took part in the election campaign of Boris Yeltsin. In 2001 he voiced his support for the Russian television TV channel NTV.[11]

After his retirement from chess in 2005, Kasparov turned to politics and created the United Civil Front, a social movement whose main goal is to "work to preserve electoral democracy in Russia."[12] He has vowed to "restore democracy" to Russia by toppling the elected Russian president Vladimir Putin, of whom he is an outspoken critic.[13][14][15]

Kasparov was instrumental in setting up The Other Russia, a coalition including Kasparov's United Civil Front, Eduard Limonov's National Bolshevik Party, Vladimir Ryzhkov's Russian Republican Party and other organizations which oppose the government of Vladimir Putin. The Other Russia has been boycotted by the leaders of Russia's democratic opposition parties, Yabloko and Union of Right Forces as they are concerned about the inclusion of radical nationalist and left-wing groups in its ranks, such as the National Bolshevik Party and former members of the Rodina party, including Viktor Gerashchenko, a potential presidential candidate. However, regional branches of Yabloko and the Union of Right Forces have opted to take part in the coalition. Kasparov says that leaders of these parties are controlled by Kremlin. [16]

On April 10, 2005, Kasparov was in Moscow at a promotional event when he was struck over the head with a chessboard he had just signed. The assailant was reported to have said "I admired you as a chess player, but you gave that up for politics" immediately before the attack.[17] Kasparov has been the subject of a number of other episodes since.[18][19]

Kasparov helped organize the Saint Petersburg Dissenters' March on March 32007 and The March of the Dissenters on March 24, 2007, both involving several thousand people rallying against Russian President Vladimir Putin and Saint Petersburg Governor Valentina Matviyenko's policies. [20][21]. On April 14, he was briefly arrested by the Moscow police while heading for a demonstration. He was held for some 10 hours, and then fined and released.[22]

He was summoned by FSB for questioning as a suspect in violations of Russian anti-extremism laws [23]. This law was previously applied for the conviction of Boris Stomakhin [24][25]

Speaking about Kasparov, former KGB general Oleg Kalugin has remarked: "I do not talk in details—people who knew them are all dead now because they were vocal, they were open. I am quiet. There is only one man who is vocal, and he may be in trouble: [former] world chess champion [Garry] Kasparov. He has been very outspoken in his attacks on Putin, and I believe that he is probably next on the list." [26]

In 1991 he received the Keeper of the Flame award from the Center for Security Policy for anti-Communist resistance and the propagation of democracy.

In April, 2007 it was asserted[27] that Garry Kasparov was a board member of the National Security Advisory Council of Center for Security Policy[28], a "non-profit, non-partisan national security organization that specializes in identifying policies, actions, and resource needs that are vital to American security"[29]. Kasparov confirmed this and added that he was removed shortly after he became aware of it. He noted that he didn't know about the membership and suggested he was included in the board by an accident because he received the 1991 Keeper of the Flame award from this organization.[30].[31]

In October 2007 Kasparov announced his intention of standing for the Russian presidency as the candidate of the "Other Russia" coalition and vowed to fight for a "democratic and just Russia".

Chess ratings achievements

- Kasparov holds the record for the longest time as the #1 rated player.

- Kasparov had the highest Elo rating in the world continuously from 1986 to 2005. The only exception is that Kramnik equalled him in the January 1996 FIDE ratings list.[32] (He was also briefly ejected from the list following his split from FIDE in 1993, but during that time he headed the rating list of the rival PCA). At the time of his retirement, he was still ranked #1 in the world, with a rating of 2812. His rating has fallen inactive since the January 2006 rating list.[33]

- According to the alternative Chessmetrics calculations, Kasparov was the highest rated player in the world continuously from February 1985 until October 2004.[34] He also holds the highest all-time average rating over a 2 (2877) to 20 (2856) year period and is second to only Bobby Fischer's (2881 vs 2879) over a one-year period.

- In January 1990 Kasparov achieved the (then) highest FIDE rating ever, passing 2800 and breaking Bobby Fischer's old record of 2785 rating. He has held the record for the highest rating ever achieved, ever since. On the July 1999 FIDE rating list Kasparov reached a 2851 Elo rating, the highest rating ever achieved.[35]

Olympiads

Kasparov played in a total of eight Olympiads. He represented the Soviet Union four times, and Russia four times, following the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991. His debut was at La Valletta 1980 as second reserve, scoring 9.5/12, when he became the youngest player ever to play for the USSR in this event, a record which still stands. In 1982, he advanced to second board at Lucerne, scoring 8.5/11. He did not play in 1984, since the World Championship match was still running at the same time. In 1986, he played first board at Dubai, again scoring 8.5/11. In 1988, he was again first board at Thessaloniki, where he made 8.5/10. All four times, the Soviet Union won the team gold medals.

Then, in 1992, he played first board for Russia at Manila, scoring 8.5/10. In 1994 at Moscow, he scored 6.5/10 on first board. In 1996 at Yerevan, he scored 7/9 on first board. His final Olympiad was Bled, Slovenia in 2002, where he scored 7.5/9 on first board. Likewise, Russia won the team gold medals all four times.

Other records held

Kasparov holds the record for most consecutive professional tournament victories, placing first or equal first in fifteen tournaments from 1981 to 1990.[citation needed]

Kasparov won the Chess Oscar a record eleven times.

Books and other writings

Kasparov has written a number of books on chess. He published a somewhat controversial autobiography when still in his early 20s, titled Unlimited Challenge. This book was subsequently updated several times after he became World Champion. Its content is mainly literary, with a small chess component of key unannotated games. He published an annotated games collection in the 1980s: Garry Kasparov: Life, Games, Career, and this book has also been updated several times in further editions. He has annotated his own games extensively for the Yugoslav Chess Informant series and for other chess publications. In 1982, he co-authored Batsford Chess Openings with British Grandmaster Raymond Keene, and this book was an enormous seller. It was updated into a second edition in 1989. He also co-authored two opening books with his trainer Alexander Sakharov in the 1980s for British publisher Batsford — on the Classical Variation of the Caro-Kann Defence and on the Scheveningen Variation of the Sicilian Defence. Kasparov has also contributed extensively to the five-volume openings series Encyclopedia of Chess Openings.

In 2003, the first volume of his five-volume work Garry Kasparov on My Great Predecessors was published. This volume, which deals with the world chess champions Wilhelm Steinitz, Emanuel Lasker, José Raúl Capablanca and Alexander Alekhine, and some of their strong contemporaries, has received lavish praise from some reviewers (including Nigel Short), while attracting criticism from others for historical inaccuracies and analysis of games directly copied from unattributed sources. Through suggestions on the book's website, most of these shortcomings were corrected in following editions and translations. Despite this, the first volume won the British Chess Federation's Book of the Year award in 2003. Volume two, covering Max Euwe, Mikhail Botvinnik, Vassily Smyslov and Mikhail Tal appeared later in 2003. Volume three, covering Tigran Petrosian and Boris Spassky appeared in early 2004. In December 2004, Kasparov released volume four, which covers Samuel Reshevsky, Miguel Najdorf, and Bent Larsen (none of these three World Chess Champions), but focuses primarily on Bobby Fischer. The fifth volume, devoted to the chess careers of Viktor Korchnoi and Anatoly Karpov, was published in March 2006.

His latest book Revolution in the 70s (published in March 2007) covers "the openings revolution of the 1970s-1980s" and is the first book in a new series called "Modern Chess Series," which intends to cover his matches with Karpov and selected games. He has also recently written How Life Imitates Chess, an examination of the parallels between decision-making in chess and in the business world.

- Garry Kasparov on Modern Chess, Part 1: Revolution in the 70s [2007, Everyman Chess]

- How Life Imitates Chess [2007 - William Heinemann Ltd ]

- My Great Predecessors Part V [2006, Everyman Chess]

- My Great Predecessors Part IV [2004, Everyman Chess]

- My Great Predecessors Part III [2004, Everyman Chess]

- Checkmate!: My First Chess Book [2004, Everyman Mindsports]

- My Great Predecessors Part II [2003, Everyman Chess]

- My Great Predecessors Part I [2003, Everyman Chess]

- Lessons in Chess [1997, Everyman Chess]

- Garry Kasparov's Chess Challenge [1996, Everyman Chess]

- Kasparov on the King's Indian [1993, B.T. Batsford Ltd]

- Kasparov Versus Karpov, 1990 [1991, Everyman Chess]

- The Queen's Indian Defence: Kasparov System [1991, B.T. Batsford Ltd]

- The Sicilian Scheveningen [1991, B.T. Batsford Ltd]

- Unlimited Challenge [1990, Grove Pr]

- London-Leningrad Championship Games [1987, Everyman Chess]

- Child of Change: An Autobiography [1987, Hutchinson]

- World Chess Championship Match: Moscow, 1985 [1986, Everyman Chess]

- Sicilian E6 and D6 Systems [1986, B.T. Batsford Ltd]

- Batsford Chess Openings [1986, B.T. Batsford Ltd]

- The Test of Time [1986, Pergamon]

- Caro-Kann: Classical 4...Bf5 [1984, B.T. Batsford Ltd]

Chess against computers

Deep Thought, 1989

Kasparov easily defeated the chess computer Deep Thought in both games of a 2-game match in 1989.

Deep Blue, 1996

In February 1996, IBM's chess computer Deep Blue defeated Kasparov in one game using normal time controls, in Deep Blue - Kasparov, 1996, Game 1. Kasparov recovered well, however, gaining three wins and two draws and easily winning the match.

Deep Blue, 1997

In May 1997, an updated version of Deep Blue defeated Kasparov 3.5-2.5 in a highly publicised six-game match. The match was level after 5 games but Kasparov was crushed in Game 6. This was the first time a computer had ever defeated a world champion in match play. A documentary film was made about this famous match-up entitled Game Over: Kasparov and the Machine.

Kasparov claimed that several factors weighed against him in this match. In particular, he was denied access to Deep Blue's recent games, in contrast to the computer's team that could study hundreds of Kasparov's.

After the loss Kasparov said that he sometimes saw deep intelligence and creativity in the machine's moves, suggesting that during the second game, human chess players, in contravention of the rules, intervened. IBM denied that it cheated, saying the only human intervention occurred between games. The rules provided for the developers to modify the program between games, an opportunity they said they used to shore up weaknesses in the computer's play revealed during the course of the match. Kasparov requested printouts of the machine's log files but IBM refused, although the company later published the logs on the Internet.[36] Kasparov demanded a rematch, but IBM declined and retired Deep Blue. Furthermore, the grandmasters employed by IBM were not seen in public during the games; in particular, they were not commenting moves during the games for the public. Unfortunately, the rules of the match didn't stipulate any provisions for making sure that IBM is playing fair.

Deep Junior, 2003

In January 2003, he engaged in a six game classical time control match with a $1 million prize fund which was billed as the FIDE "Man vs. Machine" World Championship, against Deep Junior.[37] The engine evaluated three million positions a second.[38] After one win each and three draws, it was all up to the final game. The final game of the match was televised on ESPN2 and was watched by an estimated 200-300 million people. After reaching a decent position Kasparov offered a draw, which was soon returned by the Deep Junior team. Asked why he offered the draw, Kasparov said he feared making a blunder.[39] Originally planned as an annual event, the match was not repeated.

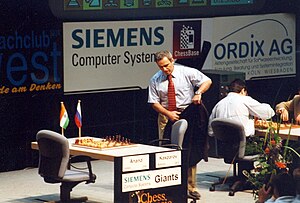

X3D Fritz, 2003

In November 2003, he engaged in a four-game match against the computer program X3D Fritz (which was said to have an estimated rating of 2807)[citation needed], using a virtual board, 3D glasses and a speech recognition system. After two draws and one win apiece, the X3D Man-Machine match ended in a draw. Kasparov received $175,000 for the result and took home the golden trophy. Kasparov continued to criticize the blunder in the second game that cost him a crucial point. He felt that he had outplayed the machine overall and played well. "I only made one mistake but unfortunately that one mistake lost the game."

Other

- Kasparov has been credited with the invention of Advanced Chess in 1998, a new form of chess in which a human and a computer play together.

- Kasparov has two European patent applications: EP1112765A4: METHOD FOR PLAYING A LOTTERY GAME AND SYSTEM FOR REALISING THE SAME from 1998, and EP0871132A1: METHOD OF PLAYING A LOTTERY GAME AND SUITABLE SYSTEM from 1995.

- Kasparov is a supporter of Anatoly Fomenko's New Chronology.[dubious – discuss]

- Kasparov gets co-credit for game design of Kasparov Chessmate, a computer chess program.

- Kasparov is a member of the International Council of the New York-based Human Rights Foundation.

See also

Notes

- ^ "Kasparov Joins Russian Presidential Race". Associated Press. 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Unlimited Challenge, an autobiography by Garry Kasparov with Donald Trelford, ISBN 0-00-637358-5

- ^ Ham, Stephen (2005). "The Young King" (PDF). Chesscafe. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "ICC Help: interview". Internet Chess Club. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ "World Chess Championship 1982-84 Candidates Matches". Mark Weeks' Chess Pages. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ 'My decision to break away from fide was a mistake', DNA, 10 September 2007. Accessed 11 September 2007.

- ^ "BGN/Dortmund Event" (Press release). This Week in Chess. 2001-09-06. Retrieved 2001-08-11.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Emma Cowing, "Kasparov makes his first political move on Putin", The Scotsman, July 13, 2006.

- ^ David Remnick, "The Tsar’s Opponent", The New Yorker, October 1, 2007.

- ^ "The Credit Suisse Blitz – in pictures". Chessbase. 2006-08-27. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Гарри Каспаров" (in Russian). Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ "Russian Chess Legend Kasparov to Establish United Civil Front". MOSNEWS.com. 2005-05-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Kasparov leads St Petersburg dissenters' demonstration against". The Independent Sunday. 2007-06-10. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Chess champ Kasparov's new gambit: politics". Chicago Sun-Times. 2005-03-12. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Why Putin will stop at nothing to smash the new Russian revolution". The Spectator. 2007-04-21. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Non-partying system"

- ^ "Pictures of the Moscow assault". The Federal Post. Chessbase. 2005-04-22. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Kasparov manhandled by police at Moscow protest". The Moscow Times. Chessbase. 2005-05-16. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Breaking news: Kasparov assaulted again". Mosnewsm.com. Chessbase. 2005-06-30. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Anti-Kremlin protesters beaten by police". CNN. 2007-03-03. Archived from the original on 2007-08-11. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Russian opposition demo quashed". BBC News. 2005-03-25. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Kasparov arrested at Moscow rally". BBC News. 2007-04-17. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Buckley, neil (2007-04-18). "Russian intelligence to quiz Kasparov over "inciting extremism"". Financial Times. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^

"Jewish Activist Convicted in Russia" (Press release). UCSJ. 2006-11-20. Retrieved 2001-08-11.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Chelysheva, Oksana (2007-04-18). "Statement from the Russian-Chechen Friendship Society following its forced closure". Front Line. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Rivkin, Amanda (July 2007). "Seven Questions: A Little KGB Training Goes a Long Way". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ "Political Death of Kasparov" (in Russian). Front Line. 2007-04-05. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Center for Security Policy Annual Report 2006" (PDF). p. 23. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ "The Center's Role in National Security Policy". Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ "1991: Keeper of the Flame Award". Center for Security Policy. 2007-04-18. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Неудобные вопросы" (in Russian). 2007-04-18. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "All Time rankings".

- ^ "FIDE Archive: Top 100 Players July 2005". World Chess Federation. 2007-04-18. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Summary 1985-2005". Chessmetrics. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ "Garry Kasparov". Chessgames. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ Kasparov versus Deep Blue - Replay the Games, IBM Research Website

- ^ "Kasparov vs Deep Junior in January 2003". ChessBase. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ "Kasparov: "Intuition versus the brute force of calculation"". CNN. 2003-02-10. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Shabazz, Damian. "Kasparov & Deep Junior fight 3-3 to draw!". The Chess Drum. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

External links

- Garry Kasparov rating card at FIDE

- Garry Kasparov player profile and games at Chessgames.com

- The Other Russia, Civic Coalition for Democracy - Official site

- Template:Ru icon Другая Россия - Official site

- Template:Ru icon Сайт «Марш несогласных» - March of the Discontented

- Template:Ru icon Итоговое заявление участников конференции «Другая Россия» Concluding statement by the participants, www.kasparov.ru

- United Civil Front, a civic political movement to ensure Democracy in the Russian Federation , initiated by Garry Kasparov

- Kasparov's political opinions

- Articles needing cleanup from October 2007

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from October 2007

- Wikipedia pages needing cleanup from October 2007

- 1963 births

- Living people

- Armenian chess players

- Armenian Russians

- Azerbaijani Jews

- World chess champions

- Chess grandmasters

- Jewish chess players

- Russian chess players

- Soviet chess players

- Russian politicians

- Russian democracy activists

- Russian dissidents

- Russian Jews

- Soviet writers

- Russian writers

- Chess writers