Locust: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 66.137.52.2 (talk) to last version by Tiddly Tom |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

[[Image:Acrididae grasshopper-2.jpg|thumb|Egyptian grasshopper ''Anacridium aegyptum'']] |

[[Image:Acrididae grasshopper-2.jpg|thumb|Egyptian grasshopper ''Anacridium aegyptum'']] |

||

[[Image:Locust from the plague in Palestine, 1915.jpg|thumb|right|Locust from the [[1915 Locust Plague]]]] |

[[Image:Locust from the plague in Palestine, 1915.jpg|thumb|right|Locust from the [[1915 Locust Plague]]]] |

||

[[Image:Locust_Tibia_Extensor_Muscle.JPG|thumb|right|Excised extensor muscle from the locust hind leg tibia]] |

|||

{{otheruses}} |

{{otheruses}} |

||

{{For|the biological nomenclature|Grasshopper}} |

{{For|the biological nomenclature|Grasshopper}} |

||

Revision as of 17:32, 1 March 2008

| Locust | |

|---|---|

| |

| Oxya yezoensis . Female(left) and male(right). | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Superclass: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

Locust is the swarming phase of short-horned grasshoppers of the family Acrididae. The origins and an apparent extinction of certain species of locust—some of which reached 6 inches (15 cm) in length—are unclear.[1]

These are species that can breed rapidly under suitable conditions and subsequently become gregarious and migratory. They form bands as nymphs and swarms as adults — both of which can travel great distances, rapidly stripping fields and greatly damaging crops.

Locust species

- Migratory locust (Locusta migratoria)

- Red locust (Nomadracis septemfasciata)

- Australian plague locust (Chortoicetes terminifera)

- American desert locust (Schistocerca americana)

- Desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria), probably the most important in terms of its very wide distribution (North Africa, Middle East, and Indian subcontinent) and its ability to migrate very widely.

- Rocky Mountain locust (Melanoplus spretus) in North America had some of the largest recorded swarms, but mysteriously died out in the late 19th century.

Though the female and the male look alike, they can be distinguished by looking at the end of their abdomen. The male has a boat-shaped tip while the female has two serrated valves that can be either apart or kept together. These valves aid in the digging of the hole in which an egg pod is deposited.

Locusts in history and literature

In the Bible, a swarm of locusts comprised the eighth plague in the story of the plagues of Egypt. Proverbs 30:27 tells us that 'the locusts have no king, yet they go forth all of them by bands', including them as one of the four little wise things. In the Book of Revelation, locusts with scorpion tails and human faces are to torment unbelievers for five months when the fifth trumpet sounds. One Old Testament book, Joel, is written in the context of a recent locust plague. Interestingly, the locusts are described in four different ways - "swarming locusts, cutting locusts, hopping locusts and destroying locusts." Although these were identified by the old Authorised Version as four different creatures, modern translations identify them as four kinds of locusts. This fits with the many molts (called instars) through which locusts go. For example, the "hopper" probably denotes the nymph stage (the first instar), the wings are not developed and the nymph hops about. For more information about the locusts in Joel, see Raymond Dillard in Minor Prophets Vol 1, ed Thomas McComiskey.

In Plato's Phaedrus, Socrates says that locusts were once human. When the Muses first brought song into the world, the beauty so captivated some people that they forgot to eat and drink until they died. The Muses turned those unfortunate souls into locusts — singing their entire lives.

In her novel On the Banks of Plum Creek, Laura Ingalls Wilder writes of a "glittering cloud" of locusts so large it blocked out the sun as it approached. The swarm descended upon her family's farm near Walnut Grove, Minnesota, destroying a year's wheat crop, and stripping the prairie bare of all vegetation.

Doris Lessing, the British writer who won the Nobel Prize for Literature for the year 2007, vividly described a locust attack in her short story titled "A Mild Attack of Locusts". The story, published in the February 26, 1956 issue of The New Yorker, is set in the South African countryside and describes how a family of farmers attempts to resist the attack, to prevent and minimize the damage and to come to terms with the loss of crops.

In Lonesome Dove by Larry McMurtry, the cow herd experiences being in the path of a swarm of locusts whose passage lasts several hours and which strips the prairie grass around them down to the nub and even chews on the cowboys' clothing.

Locusts as experimental model

Locusts are used as models in many fields of biology especially in the field of olfactory, visual and locomotor neurophysiology. It is one of the organisms for which scientists have obtained detailed data on information processing in the olfactory pathway of organisms. It is suitable for the above purposes because of the robustness of the preparation for electrophysiological experiments and ease of growing them.

Swarming behaviour and extinctions

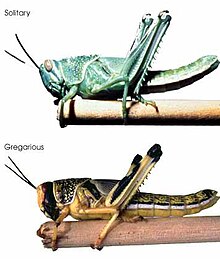

Research at Cambridge University has identified swarming behaviour as a response to overcrowding. Triggered by increased tactile stimulation of the hind legs, transformation of the locust to the swarming variety is merely induced by several contacts per minute over a four hour period.[2] It is estimated that the largest swarms have covered hundreds of square miles and consisted of many billions of locusts.

The extinction of the Rocky Mountain locust has been a source of puzzlement. Recent research suggests that the breeding grounds of this insect in the valleys of the Rocky Mountains came under sustained agriculture development during the large influx of gold miners [1], destroying the underground eggs of the locust.[3] Entomologist Jeffrey A. Lockwood investigated these changes and detailed them in his book Locust: The Devastating Rise and Mysterious Disappearance of the Insect that Shaped the American Frontier.

Related uses of the word "locust"

The words "lobster" and "locust" are both derived from the Vulgar Latin locusta, which was originally used to refer to various types of crustaceans and insects.[4] Spanish has mostly preserved the original Latin usage, since the cognate term langosta can be used to refer both to a variety of lobster-like crustaceans and to the swarming grasshopper, while semantic confusion is avoided by employing qualifiers such as de tierra (of the land) when referring to grasshoppers, de mar and de rio (of the sea/of the river) when referring to lobsters and crayfish respectively.[5] [6]. French presents an inverse case, during the 16th century the word sauterelle (literally "little hopper") could mean either grasshopper or lobster (sauterelle de mer).[7] [8] In contemporary French usage langouste is used almost exclusively to refer to the crustacean (two insect exceptions being the langouste de désert and the langouste de Provence).[9] [10] In certain regional varieties of English "locust" can refer to the large swarming grasshopper, the cicada (which may also swarm), and rarely to the praying mantis ("praying locust").[11]

The use of "locust" in English as a synonym for "lobster" has no grounding in anglophone tradition, and most modern instances of its use are usually calques of foreign expressions (e.g. "sea locust" as mistranslation of langouste de mer).[12] There are, however, various species of crustaceans whose regional names include the word "locust." Thenus orientalis, for example, is sometimes referred to as the Flathead locust lobster (its French name, Cigale raquette, literally "raquet cicada," is yet another instance of the locust-cicada-lobster nomenclatural connection).[13] Similarly, certain types of amphibians and birds are sometimes called "false locusts" in imitation of the Greek pseud(o)acris, a scientific name sometimes given to a species because of its perceived cricket-like chirping.[14] Often the linguistic non-differentiation of animals that not only are regarded by science as different species, but that often exist in radically different environments is the result of culturally perceived similarities between organisms, as well as of abstract associations formed within a particular group's mythology and folklore (see Cicada mythology). On a linguistic level, these cases also exemplify an extensively documented tendency, in many languages, towards conservatism and economy in neologization, with some languages historically only allowing for the expansion of meaning within already existing word-forms.[15] Also of note is the fact that all three so-called locusts (the grasshopper, the cicada, and the lobster) have been a traditional source of food for various peoples around the world (see entomophagy).

The word "locust" has, at times, been employed controversially in English translations of Ancient Greek and Latin natural histories, as well as of Hebrew and Greek Bibles; such ambiguous renderings prompted the 17th century polymath Thomas Browne to include in the Fifth Book of his Pseudodoxia Epidemica an essay entitled Of the Picture of a Grashopper, it begins:

THERE is also among us a common description and picture of a Grashopper, as may be observed in the pictures of Emblematists, in the coats of severals families, and as the word Cicada is usually translated in Dictionaries. Wherein to speak strictly, if by this word Grashopper, we understand that animal which is implied by τέτιξ (tettix) with the Greeks, and by Cicada with the Latines; we may with safety affirm the picture is widely mistaken, and that for ought enquiry can inform, there is no such insect in England.[16]

Browne revisited the controversy in his Miscellany Tracts (1684), wherein he takes pains (even citing Aristotle's Animalia) to both indicate the relationship of locusts to grasshoppers and to affirm their like disparateness from cicadas:

That which we commonly call a Grashopper, and the French Saulterelle being one kind of Locust, so rendered in the plague of Ægypt, and in old Saxon named Gersthop.[17]

Compound-words involving "locust" have also been used by anglophone translators as calques of archaic Arabic, Greek, Hebrew, or other language names for animals; the resulting formations have, just as in the case of the Brownian grasshopper/cicada controversy, been, at times, a cause of lexical ambiguity and false polysemy in English. An instance of this appears in a translation of Pliny included in J.W. McCrindle's book Ancient India as Described in Classical Literature, where an Indian gem is said by the Roman historian to have a "surface [that] is even redder than the shells of the sea-locust."[18]

See also

External links

- FAO Locust Watch

- Desert Locust Meteorological Monitoring at Sahel Resources

- Locust Video

- USAID Supplemental Environmental Assessment of the Ertirean Locust Control Program [1]

References

- ^ a b Encarta Reference Library Premium 2005 DVD. Article - Rocky Mountain Locust.

- ^ Mechanosensory-induced behavioural gregarization in the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria

- ^ Ryckman, Lisa Levitt (1999-06-22). "The Great Locust Mystery". Rocky Mountain News. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Lobster Derivatives

- ^ DICCIONARIO DE LA LENGUA ESPAÑOLA

- ^ Translations for: Crayfish

- ^ Histoire entière des poissons

- ^ sauterelle de mer

- ^ Diseases and pests of animals and plants

- ^ La Saga des Magiciennes dentelées

- ^ Of the erectness of man

- ^ Marseille Dining

- ^ Flathead locust lobster

- ^ Pseudoacris crucifer

- ^ Language: An Introduction to the Study of Speech

- ^ Of the Picture of a Grashopper

- ^ An Answer to Certain Queries Relating to Fishes, Birds, and Insects

- ^ Pliny: Indian Minerals and Precious Stones