Ivan the Terrible: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

IM SOO HOOD |

|||

im a very ugly man |

|||

{{Redirect|Ivan the Terrible}} |

{{Redirect|Ivan the Terrible}} |

||

{{Infobox Monarch |

{{Infobox Monarch |

||

Revision as of 14:59, 27 March 2008

IM SOO HOOD

| Ivan IV Ivan the Terrible | |

|---|---|

| Grand Prince of Moscow Tsar of all Russia | |

| |

| Reign | 3 December, 1533 - 18 March, 1584 |

| Coronation | 16 January, 1547 |

| Predecessor | Vasili III |

| Successor | Feodor I |

| Issue | Feodor I |

| Dynasty | Rurik |

| Father | Vasili III |

| Mother | Elena Glinskaya |

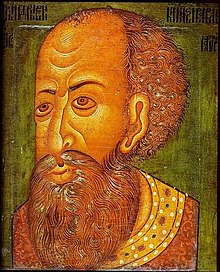

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (Russian: Ива́н четвёртый, Васи́льевич) (August 25, 1530, Moscow – March 18, 1584, Moscow) was the Grand Prince of Moscow from 1533 to 1547 and was the first ruler of Russia to assume the title of tsar (or czar). His long reign saw the conquest of Tartary and Siberia and subsequent transformation of Russia into a multiethnic and multiconfessional state. This tsar is known in the Russian tradition as Ivan Grozny (Russian: Ива́н Гро́зный ), which is traditionally translated into English as Ivan the Terrible.

Early reign

Ivan was a long-awaited son of Vasili III. When Ivan was just three years old his father died from a boil and inflammation on his leg which developed into blood poisoning. Ivan was proclaimed the Grand Prince of Moscow at his father’s request. At first, his mother Yelena Glinskaya acted as a regent, but she died when Ivan was merely eight years old. She was replaced as regent by boyars from the Shuisky family until Ivan assumed power in 1544. According to his own letters, Ivan customarily felt neglected and offended by the mighty boyars from the Shuisky and Belsky families. (These traumatic experiences may have contributed to his hatred of the boyars and to his mental instability. Alternatively, the negative feelings revealed in his letters may have been a reflection of his disagreeable temperament.)

Ivan was crowned king with Monomakh's Cap at the Cathedral of the Dormition at age sixteen on January 16, 1547. Despite calamities triggered by the Great Fire of 1547, the early part of his reign was one of peaceful reforms and modernization. Ivan revised the law code (known as the sudebnik), created a standing army (the streltsy), established the first Russian parliament of the feudal estates (the Zemsky Sobor), the council of the nobles (known as the Chosen Council), and confirmed the position of the Church with the Council of the Hundred Chapters, which unified the rituals and ecclesiastical regulations of the entire country. He introduced the local self-management in rural regions, mainly in the Northeast of Russia, populated by the state peasantry. During his reign the first printing press was introduced to Russia (although the first Russian printers Ivan Fedorov and Pyotr Mstislavets had to flee from Moscow to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania).

In 1547 Hans Schlitte, the agent of Ivan, employed handicraftsmen in Germany for work in Russia. However all these handicraftsmen were arrested in Lübeck at the request of Poland and Livonia. The German merchant companies ignored the new port built by Ivan on the river Narva in 1550 and continued to deliver goods in the Baltic ports owned by Livonia. Russia remained isolated from sea trade.

Ivan formed new trading connections, opening up the White Sea and the port of Arkhangelsk to the Muscovy Company of English merchants. In 1552 he defeated the Kazan Khanate, whose armies had repeatedly devastated the Northeast of Russia,[1] and annexed its territory. In 1556, he annexed the Astrakhan Khanate and destroyed the largest slave market on the river Volga. These conquests complicated the migration of the aggressive nomadic hordes from Asia to Europe through Volga and transformed Russia into a multinational and multiconfessional state. He had St. Basil's Cathedral constructed in Moscow to commemorate the seizure of Kazan. Legend has it that he was so impressed with the structure that he had the architects blinded, so that they could never design anything as beautiful again.

Other events of this period include the introduction of the first laws restricting the mobility of the peasants, which would eventually lead to serfdom, and change in Ivan's personality, traditionally linked to his near-fatal illness in 1553 and the death of his first wife, Anastasia Romanovna in 1560. Ivan suspected boyars of poisoning his wife and of plotting to replace him on the throne with his cousin, Vladimir of Staritsa. In addition, during that illness Ivan had asked the boyars to swear an oath of allegiance to his eldest son, an infant at the time. Many boyars refused, deeming the tsar's health too hopeless to survive. This angered Ivan and added to his distrust of the boyars. There followed brutal reprisals and assassinations, including those of Metropolitan Philip and Prince Alexander Gorbatyi-Shuisky.

The 1565 formation of the Oprichnina was also significant. The Oprichnina was the section of Russia (mainly the Northeast) directly ruled by Ivan and policed by his personal servicemen, the Oprichniki. This system of Oprichnina has been viewed by some historians as a tool against the omnipotent hereditary nobility of Russia (boyars) who opposed the absolutist drive of the tsar, while others have interpreted it as a sign of the paranoia and mental deterioration of the tsar.

Later reign

The later half of Ivan's reign was far less successful. Although Khan Devlet I Giray of Crimea repeatedly devastated the Moscow region and even set Moscow on fire in 1571, the Czar supported Yermak's conquest of Tatar Siberia, adopting a policy of empire-building, which led him to launch a victorious war of seaward expansion to the west, only to find himself fighting the Swedes, Lithuanians, Poles, and the Livonian Teutonic Knights.

For twenty-four years the Livonian War dragged on, damaging the Russian economy and military and failing to gain any territory for Russia. In the 1560s the combination of drought and famine, Polish-Lithuanian raids, Tatar invasions, and the sea-trading blockade carried out by the Swedes, Poles and the Hanseatic League devastated Russia. The price of grain increased by a factor of ten. Epidemics of the plague killed 10,000 in Novgorod. In 1570 the plague killed 600-1000 in Moscow daily.[2] Ivan's closest advisor, Prince Andrei Kurbsky, defected to the Lithuanians, headed the Lithuanian troops and devastated the Russian region of Velikiye Luki. This treachery deeply hurt Ivan. As the Oprichnina continued, Ivan became mentally unstable and physically disabled. In one week, he could easily pass from the most depraved orgies to prayers and fasting in a remote northern monastery.

Because he gradually grew unbalanced and violent, the Oprichniks under Malyuta Skuratov soon got out of hand and became murderous thugs. They massacred nobles and peasants, and conscripted men to fight the war in Livonia. Depopulation and famine ensued. What had been by far the richest area of Russia became the poorest. In a dispute with the wealthy city of Novgorod, Ivan ordered the Oprichniks to murder inhabitants of this city, which was never to regain its former prosperity. His followers burned and pillaged the city and villages.[3] As many as 60,000 might have been killed during the infamous Massacre of Novgorod in 1570;[4][3][5] many others were deported elsewhere.[5] Yet the official death toll named 1,500 of Novgorod big people (nobility) and only mentioned about the same number of smaller people. Many modern researchers estimate number of victims between two and three thousand. (After the famine and epidemics of 1560s the population of Novgorod perhaps did not exceed 10,000-20,000.)[6]

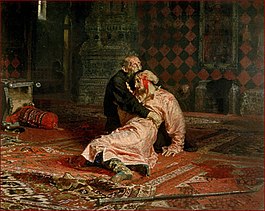

In 1581, Ivan beat his pregnant daughter-in-law for wearing immodest clothing, which may have caused a miscarriage. His son, also named Ivan, upon learning of this, engaged in a heated argument with his father, which resulted in Ivan striking his son in the head with his pointed staff, causing his son's (accidental) death. This event is depicted in the famous painting by Ilya Repin, Ivan the Terrible and his son Ivan on Friday, November 16, 1581 better known as Ivan the Terrible killing his son.

Death and legacy

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2007) |

Although it is thought by many that Ivan died while setting up a chess board, it is more likely that he died while playing chess with Bogdan Belsky on March 18, 1584. When Ivan's tomb was opened during renovations in the 1960s, his remains were examined and discovered to contain very high amounts of mercury, indicating a high probability that he was poisoned. Modern suspicion falls on his advisors Belsky and Boris Godunov (who became tsar in 1598). Three days earlier, Ivan had allegedly attempted to rape Irina, Godunov's sister and Feodor's wife. Her cries attracted Godunov and Belsky to the noise, whereupon Ivan let Irina go, but Belsky and Godunov considered themselves marked for death. The tradition says that they either poisoned or strangled Ivan in fear for their own lives. The mercury found in Ivan's remains may also be related to treatment for syphilis, which it is speculated that Ivan had. This same investigation that was done right after Stalin's death, revealed that Ivan had also suffered many years from rheumatoid arthritis, which also was treated with mercurials. It is well known that one of the end stages of syphilis (Tertiary Syphilis) many times results in severe disseminated arthritis. Not only can heavy metal (mercury) poisoning lead to violent mood swings, but so does Tertiary Syphilis, i.e., Idi Amin. Upon Ivan's death, the ravaged kingdom was left to his unfit and childless son Feodor.

Epistles

D.S. Mirsky called Ivan "a pamphleteer of genius". The epistles attributed to him are the masterpieces of old Russian (perhaps all Russian) political journalism. They may be too full of texts from the Scriptures and the Fathers, and their Church Slavonic is not always correct. But they are full of cruel irony, expressed in pointedly forcible terms.

The shameless bully and the great polemicist are seen together in a flash when he taunts runaway Kurbsky with the question: "If you are so sure of your righteousness, why did you run away and not prefer martyrdom at my hands?" Such strokes were well calculated to drive his correspondent into a rage. "The part of the cruel tyrant elaborately upbraiding an escaped victim while he continues torturing those in his reach may be detestable, but Ivan plays it with truly Shakespearian breadth of imagination".[7].

Besides his letters to Kurbsky he wrote other satirical invectives to men in his power. The best is his letter to the abbot of the Kirillo-Belozersky Monastery, where he pours out all the poison of his grim irony on the unascetic life of the boyars, shorn monks, and those exiled by his order. His picture of their luxurious life in the citadel of ascetism is a masterpiece of trenchant sarcasm.

Sobriquet

The English word terrible is usually used to translate the Russian word grozny in Ivan's nickname, but the modern English usage of terrible, with a pejorative connotation of bad or evil, does not precisely represent the intended meaning. Grozny's meaning is closer to the original usage of terrible—inspiring fear or terror, dangerous (as in Old English in one's danger), formidable, threatening, or awesome. Perhaps a translation closer to the intended sense would be Ivan the Fearsome, or Ivan the Formidable.

See also

- Ivan the Terrible in Russian folklore

- Ivan the Terrible - the film by Sergei Eisenstein.

- Ivan Vasilievich: Back to the Future - the film by Leonid Gaidai

Notes

- ^ Russian chronicles record about forty attacks of Kazan Khans on the Russian territories (mainly the regions of Nizhniy Novgorod, Murom, Vyatka, Vladimir, Kostroma, and Galich) in the first half of the 16th century. In 1521, the combined forces of Khan Muhamed Giray and his Crimean allies attacked Russia and captured more than 150,000 slaves. The Full Collection of the Russian Annals, vol.13, SPb, 1904

- ^ R.Skrynnikov, "Ivan Grosny", M., AST, 2001

- ^ a b Novgorod, Russia (Capital)

- ^ Ivan the Terrible, Russia, (r.1533-84)

- ^ a b According to the Third Novgorod Chronicle, the massacre lasted for five weeks. Almost every day 500 or 600 people were killed or drowned. The First Pskov Chronicle estimates the number of victims at 60,000.

- ^ Having investigated the report of Maljuta Skuratov and commemoration lists (sinodiki), R. Skrynnikov considers, that the number of victims was 2,000-3,000. (Skrynnikov R. G., "Ivan Grosny", M., AST, 2001)

- ^ D.S. Mirsky. A History of Russian Literature. Northwestern University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8101-1679-0. Page 21.

References

- Bobrick, Benson. Ivan the Terrible. Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 1990 (hardcover, ISBN 0-86241-288-9).

- Madariaga, Isabel de. Ivan the Terrible. First Tsar of Russia. New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2005 (hardcover, ISBN 0-300-09757-3); 2006 (paperback, ISBN 0-300-11973-9).

- Payne, Robert; Romanoff, Nikita. Ivan the Terrible. Lanham, MD: Cooper Square Press, 2002 (paperback, ISBN 0-8154-1229-0).

- Troyat, Henri. Ivan the Terrible. New York: Buccaneer Books, 1988 (hardcover, ISBN 0-88029-207-5); London: Phoenix Press, 2001 (paperback, ISBN 1-84212-419-6).

- Ivan IV, World Book Inc, 2000. World Book Encyclopedia.

Further reading

- Cherniavsky, Michael. "Ivan the Terrible as Renaissance Prince", Slavic Review, Vol. 27, No. 2. (Jun., 1968), pp. 195–211.

- Hunt, Priscilla. "Ivan IV's Personal Mythology of Kingship", Slavic Review, Vol. 52, No. 4. (Winter, 1993), pp. 769–809.

- Perrie, Maureen. The Image of Ivan the Terrible in Russian Folklore (Cambridge Studies in Oral and Literate Culture; 14). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987 (hardcover, ISBN 0-521-33075-0); 2002 (paperback, ISBN 0-521-89100-0).

- Perrie, Maureen. The Cult of Ivan the Terrible in Stalin's Russia (Studies in Russian and Eastern European History and Society) . New York: Palgrave, 2001 (hardcopy, ISBN 0-333-65684-9).

- Perrie, Maureen; Pavlov, Andrei. Ivan the Terrible (Profiles in Power). Harlow, UK: Longman, 2003 (paperback, ISBN 0-582-09948-X).

- Platt, Kevin M.F.; Brandenberger, David. "Terribly Romantic, Terribly Progressive, or Terribly Tragic: Rehabilitating Ivan IV under I.V. Stalin", Russian Review, Vol. 58, No. 4. (Oct., 1999), pp. 635–654.