Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde: Difference between revisions

seperating summary of book from the history |

|||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

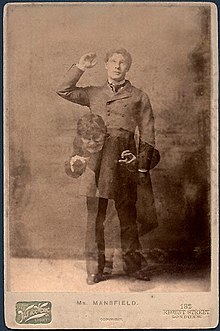

[[Image:Jekyll-mansfield.jpg|thumb|left|[[Richard Mansfield]] was mostly known for his dual role depicted in this double exposure. The stage adaptation opened in London in 1887, a year after the publication of the novella. Picture 1895.]] |

[[Image:Jekyll-mansfield.jpg|thumb|left|[[Richard Mansfield]] was mostly known for his dual role depicted in this double exposure. The stage adaptation opened in London in 1887, a year after the publication of the novella. Picture 1895.]] |

||

==Summary== |

|||

On their weekly walk, an eminently sensible, trustworthy lawyer named Mr. Utterson listens as his friend Enfield tells a gruesome tale of assault. The tale describes a sinister figure named Mr. Hyde who tramples a young girl, disappears into a door on the street, and reemerges to pay off her relatives with a check signed by a respectable gentleman. Since both Utterson and Enfield disapprove of gossip, they agree to speak no further of the matter. It happens, however, that one of Utterson’s clients and close friends, Dr. Jekyll, has written a will transferring all of his property to this same Mr. Hyde. Soon, Utterson begins having dreams in which a faceless figure stalks through a nightmarish version of London. |

On their weekly walk, an eminently sensible, trustworthy lawyer named Mr. Utterson listens as his friend Enfield tells a gruesome tale of assault. The tale describes a sinister figure named Mr. Hyde who tramples a young girl, disappears into a door on the street, and reemerges to pay off her relatives with a check signed by a respectable gentleman. Since both Utterson and Enfield disapprove of gossip, they agree to speak no further of the matter. It happens, however, that one of Utterson’s clients and close friends, Dr. Jekyll, has written a will transferring all of his property to this same Mr. Hyde. Soon, Utterson begins having dreams in which a faceless figure stalks through a nightmarish version of London. |

||

Puzzled, the lawyer visits Jekyll and their mutual friend Dr. Lanyon to try to learn more. Lanyon reports that he no longer sees much of Jekyll, since they had a dispute over the course of Jekyll’s research, which Lanyon calls “unscientific balderdash.” Curious, Utterson stakes out a building that Hyde visits—which, it turns out, is a laboratory attached to the back of Jekyll’s home. Encountering Hyde, Utterson is amazed by how undefinably ugly the man seems, as if deformed, though Utterson cannot say exactly how. Much to Utterson’s surprise, Hyde willingly offers Utterson his address. Jekyll tells Utterson not to concern himself with the matter of Hyde. |

Puzzled, the lawyer visits Jekyll and their mutual friend Dr. Lanyon to try to learn more. Lanyon reports that he no longer sees much of Jekyll, since they had a dispute over the course of Jekyll’s research, which Lanyon calls “unscientific balderdash.” Curious, Utterson stakes out a building that Hyde visits—which, it turns out, is a laboratory attached to the back of Jekyll’s home. Encountering Hyde, Utterson is amazed by how undefinably ugly the man seems, as if deformed, though Utterson cannot say exactly how. Much to Utterson’s surprise, Hyde willingly offers Utterson his address. Jekyll tells Utterson not to concern himself with the matter of Hyde. |

||

Revision as of 00:55, 16 April 2008

Title page of the first London edition (1886) | |

| Author | Robert Louis Stevenson |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Longmans, Green & co. |

Publication date | January 1886 |

| Publication place | Scotland |

Template:Otheruses2 Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde[1] is a novella written by the Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson and first published in 1886. It is about a London lawyer who investigates strange occurrences between his old friend, Dr Henry Jekyll[2], and the misanthropic Edward Hyde. The work is known for its vivid portrayal of the psychopathology of a split personality; in mainstream culture the very phrase "Jekyll and Hyde" has come to mean a person who may show a distinctly different character, or profoundly different behaviour, from one situation to the next, as if almost another person, possibly because of the rare disorder "multiple personality disorder".

Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was an immediate success and one of Stevenson's best-selling works. Stage adaptations began in Boston and London within a year of its publication and it has gone on to inspire scores of major film and stage performances.

History

Stevenson had long been interested in the idea of the duality of human nature and how to incorporate the interplay of good and evil into a story. While still a teenager, he developed a script for a play on Deacon Brodie, which he later reworked with the help of W. E. Henley and saw produced for the first time in 1882.[3] In the late 1884 he wrote the short story "Markheim," which he revised in 1885 for publication in a Christmas annual. One night in late September or early October of 1885, possibly while he was still revising "Markheim," Stevenson had a dream, and on wakening had the intuition for two or three scenes that would appear in the story. "In the small hours of one morning," says Mrs Stevenson, "I was awakened by cries of horror from Louis. Thinking he had a nightmare, I woke him. He said angrily, 'Why did you wake me? I was dreaming a fine bogey tale.' I had awakened him at the first transformation scene ..."

Lloyd Osbourne, Stevenson's stepson, remembers, "I don't believe that there was ever such a literary feat before as the writing of Dr. Jekyll. I remember the first reading as if it were yesterday. Louis came downstairs in a fever; read nearly half the book aloud; and then, while we were still gasping, he was away again, and busy writing. I doubt if the first draft took so long as three days."

As was the custom, Mrs Stevenson would read the draft and offer her criticisms in the margins. Louis was confined to bed at the time from a haemorrhage, and she left her comments with the manuscript and Louis in the bedroom. She said in effect the story was really an allegory, but Louis was writing it just as a story. After a while Louis called her back into the bedroom and pointed to a pile of ashes: he had burnt the manuscript in fear that he would try to salvage it, and in the process forcing himself to start over from scratch writing an allegorical story as she had suggested. Scholars debate if he really burnt his manuscript or not. Other scholars suggest her criticism was not about allegory, but about inappropriate sexual content. Whatever the case, there is no direct factual evidence for the burning of the manuscript, but it remains an integral part of the history of the novella.

Stevenson re-wrote the story again in three days. According to Osbourne, "The mere physical feat was tremendous; and instead of harming him, it roused and cheered him inexpressibly." He refined and continued to work on it for 4 to 6 weeks afterward.

Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was initially sold as a paperback for one shilling in the UK and one dollar in the U.S. Initially stores would not stock it until a review appeared in The Times, on 25 January 1886, giving it a favourable reception. Within the next six months close to forty thousand copies were sold. By 1901 it was estimated to have sold over 250,000 copies. Its success was probably due more to the "moral instincts of the public" than perception of its artistic merits, being widely read by those who never otherwise read fiction, quoted in pulpit sermons and in religious papers[citation needed].

Summary

On their weekly walk, an eminently sensible, trustworthy lawyer named Mr. Utterson listens as his friend Enfield tells a gruesome tale of assault. The tale describes a sinister figure named Mr. Hyde who tramples a young girl, disappears into a door on the street, and reemerges to pay off her relatives with a check signed by a respectable gentleman. Since both Utterson and Enfield disapprove of gossip, they agree to speak no further of the matter. It happens, however, that one of Utterson’s clients and close friends, Dr. Jekyll, has written a will transferring all of his property to this same Mr. Hyde. Soon, Utterson begins having dreams in which a faceless figure stalks through a nightmarish version of London. Puzzled, the lawyer visits Jekyll and their mutual friend Dr. Lanyon to try to learn more. Lanyon reports that he no longer sees much of Jekyll, since they had a dispute over the course of Jekyll’s research, which Lanyon calls “unscientific balderdash.” Curious, Utterson stakes out a building that Hyde visits—which, it turns out, is a laboratory attached to the back of Jekyll’s home. Encountering Hyde, Utterson is amazed by how undefinably ugly the man seems, as if deformed, though Utterson cannot say exactly how. Much to Utterson’s surprise, Hyde willingly offers Utterson his address. Jekyll tells Utterson not to concern himself with the matter of Hyde. A year passes uneventfully. Then, one night, a servant girl witnesses Hyde brutally beat to death an old man named Sir Danvers Carew, a member of Parliament and a client of Utterson. The police contact Utterson, and Utterson suspects Hyde as the murderer. He leads the officers to Hyde’s apartment, feeling a sense of foreboding amid the eerie weather—the morning is dark and wreathed in fog. When they arrive at the apartment, the murderer has vanished, and police searches prove futile. Shortly thereafter, Utterson again visits Jekyll, who now claims to have ended all relations with Hyde; he shows Utterson a note, allegedly written to Jekyll by Hyde, apologizing for the trouble he has caused him and saying goodbye. That night, however, Utterson’s clerk points out that Hyde’s handwriting bears a remarkable similarity to Jekyll’s own. For a few months, Jekyll acts especially friendly and sociable, as if a weight has been lifted from his shoulders. But then Jekyll suddenly begins to refuse visitors, and Lanyon dies from some kind of shock he received in connection with Jekyll. Before dying, however, Lanyon gives Utterson a letter, with instructions that he not open it until after Jekyll’s death. Meanwhile, Utterson goes out walking with Enfield, and they see Jekyll at a window of his laboratory; the three men begin to converse, but a look of horror comes over Jekyll’s face, and he slams the window and disappears. Soon afterward, Jekyll’s butler, Mr. Poole, visits Utterson in a state of desperation: Jekyll has secluded himself in his laboratory for several weeks, and now the voice that comes from the room sounds nothing like the doctor’s. Utterson and Poole travel to Jekyll’s house through empty, windswept, sinister streets; once there, they find the servants huddled together in fear. After arguing for a time, the two of them resolve to break into Jekyll’s laboratory. Inside, they find the body of Hyde, wearing Jekyll’s clothes and apparently dead by suicide—and a letter from Jekyll to Utterson promising to explain everything. Utterson takes the document home, where first he reads Lanyon’s letter; it reveals that Lanyon’s deterioration and eventual death were caused by the shock of seeing Mr. Hyde take a potion and metamorphose into Dr. Jekyll. The second letter constitutes a testament by Jekyll. It explains how Jekyll, seeking to separate his good side from his darker impulses, discovered a way to transform himself periodically into a deformed monster free of conscience—Mr. Hyde. At first, Jekyll reports, he delighted in becoming Hyde and rejoiced in the moral freedom that the creature possessed. Eventually, however, he found that he was turning into Hyde involuntarily in his sleep, even without taking the potion. At this point, Jekyll resolved to cease becoming Hyde. One night, however, the urge gripped him too strongly, and after the transformation he immediately rushed out and violently killed Sir Danvers Carew. Horrified, Jekyll tried more adamantly to stop the transformations, and for a time he proved successful; one day, however, while sitting in a park, he suddenly turned into Hyde, the first time that an involuntary metamorphosis had happened while he was awake. The letter continues describing Jekyll’s cry for help. Far from his laboratory and hunted by the police as a murderer, Hyde needed Lanyon’s help to get his potions and become Jekyll again—but when he undertook the transformation in Lanyon’s presence, the shock of the sight instigated Lanyon’s deterioration and death. Meanwhile, Jekyll returned to his home, only to find himself ever more helpless and trapped as the transformations increased in frequency and necessitated even larger doses of potion in order to reverse themselves. It was the onset of one of these spontaneous metamorphoses that caused Jekyll to slam his laboratory window shut in the middle of his conversation with Enfield and Utterson. Eventually, the potion began to run out, and Jekyll was unable to find a key ingredient to make more. His ability to change back from Hyde into Jekyll slowly vanished. Jekyll writes that even as he composes his letter he knows that he will soon become Hyde permanently, and he wonders if Hyde will face execution for his crimes or choose to kill himself. Jekyll notes that, in any case, the end of his letter marks the end of the life of Dr. Jekyll. With these words, both the document and the novel come to a close.

Analysis

This novel represents a concept in Western culture, that of the inner conflict of humanity's sense of good and evil [4]. It has also been noted as "one of the best guidebooks of the Victorian era because of its piercing description of the fundamental dichotomy of the 19th century outward respectability and inward lust" as it had a tendency for social hypocrisy[5].

Various direct influences have been suggested for Stevenson's interest in the mental condition that separates the sinful from moral self. Among them are the Biblical text of Romans (7:20 "Now if I do that I would not, it is no more I that do it, but sin that dwelleth in me."); the split life in the 1780s of Edinburgh city councillor Deacon William Brodie, master craftsman by day, burglar by night; and James Hogg's novel The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824), in which a young man falls under the spell of the devil.

Literary genres which critics have applied as a framework for interpreting the novel include religious allegory, fable, detective story, sensation fiction, science fiction, doppelgänger literature, Scottish devil tales and gothic novel.

Stevenson never says exactly what Hyde takes pleasure in on his nightly forays, saying generally that it is something of an evil and lustful nature; thus it is in the context of the times, abhorrent to Victorian religious morality. However scientists in the closing decades of the 19th century, within a post-Darwinian perspective, were also beginning to examine various biological influences on human morality, including drug and alcohol addiction, homosexuality, multiple personality disorder, and regressive animality.[6]

Jekyll's inner division has been viewed by some critics as analogous to schisms existing in British society. Divisions include the social divisions of class, the internal divisions within the Scottish identity, the political divisions between Ireland and England, and the divisions between religious and secular forces.[citation needed]

The . novel can be seen as an expression of the dualist tendency in Scottish culture, a forerunner to what G. Gregory Smith termed the 'Caledonian Antisyzygy' (the combination of opposites) which influenced the 20th Scottish cultural renaissance led by Hugh MacDiarmid. The London depicted in the novel resembles more closely the Old Town of Edinburgh which Stevenson frequented in his youth, itself a doppelganger to the city's respectable, classically ordered New Town. Scottish critics have also read it as a metaphor of the opposing forces of Scottish Presbyterianism and Scotland's atheistic Enlightenment.

In the arts

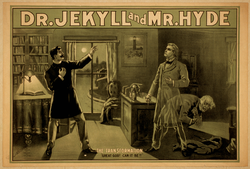

There have been dozens of major stage and film adaptations, and countless references in popular culture. The very phrase "Jekyll and Hyde" has become shorthand to mean wild or controversial and polar behaviour. Most adaptations of the work omit the reader-identification figure of Utterson, instead telling the story from Jekyll and Hyde's viewpoint, thus eliminating the mystery aspect of the tale about who Hyde is; indeed there have been no major adaptations to date that stay close to Stevenson's original work, almost all introducing some form of romantic element.

For a complete list of derivative works see "Derivative works of Robert Louis Stevenson (by Richard Dury). There have been over 123 film versions, not including stage, radio etc. This is not an inclusive list, but includes major and notable adaptations listed in chronological order:

- 1887, stage play, opened in Boston. Thomas Russell Sullivan's Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. This was the first serious theatrical rendering, it went on to tour Britain and ran for 20 years. It became forever linked with Richard Mansfield's performance, who continued playing the part up until his death in 1907. Sullivan re-worked the plot to center around a domestic love interest.

- 1912, movie USA, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Thanhouser Company Directed by Lucius Henderson starring James Cruze amd Florence Labadie

- 1920, movie USA, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Directed by John S. Robertson. The most famous of the silent film versions, starring an inspired John Barrymore in a bravura performance. Plot follows the Sullivan version of 1887, with some elements from The Picture of Dorian Gray.

- 1920, movie USA, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Directed by J. Charles Haydon.

- 1920, movie Germany, Der Januskopf (literally, "The Janus-Head," Janus being a Roman God usually depicted with two faces). Directed by F.W. Murnau. An unauthorized version of Stevenson's story, disguised by changing the names to Dr Warren and Mr O'Connor. (Murnau more famously filmed an unauthorized version of Dracula in 1922's Nosferatu.) The dual roles were essayed by Conrad Veidt. The film is now lost.

- 1931, movie USA, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Directed by Rouben Mamoulian. Widely viewed as the classic film version, known for its skilled acting, powerful visual symbolism, and innovative special effects. Follows the Sullivan plot. Fredric March won the Academy Award for his deft portrayal and the technical secret of the amazing transformation scenes wasn't revealed until after the director's death decades later. "This is when JEEK-ull (/ˈdʒiːkəl/) became JEK-ull (/ˈdʒɛkəl/), the movie pronunciation."[7]

- 1941, movie U.S., Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Directed by Victor Fleming. Largely an imitation of the 1931 movie, it stars Spencer Tracy, Ingrid Bergman, and Lana Turner.

- 1955, TV U.S., Hyde and Hare. Directed by Friz Freleng. Bugs Bunny Meets Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde.

- 1959, made-for-TV movie France, The Testament of Dr. Cordelier. Directed by Jean Renoir. A quite original modern adaptation of Stevenson's novel, it stars Jean-Louis Barrault, Teddy Bilis, and Michel Vitold.

- 1960, movie UK, The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll (released in the US as House of Fright and Jekyll's Inferno). Directed by Terence Fisher. A lurid love triangle and explicit scenes of snakes, opium dens, rape, murder and bodies crashing through glass roofs. Notable in that an aged and ineffectual Dr Jekyll becomes handsome and virile (but evil) Mr Hyde.

- 1963, movie USA, The Nutty Professor. Directed by Jerry Lewis. This screwball comedy retains a thin plot connection to the original work. Its enduring popularity has given it a significant role in the cultural visibility of the Jekyll and Hyde motif. Lewis re-works the Victorian polarised identity theme to the mid-20th century American dilemma of masculinity.

- 1968, TV U.S. and Canada, "Robert Louis Stevenson's The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde". Starring Jack Palance, directed by Charles Jarrott and produced by Dan Curtis of Dark Shadows fame. Shown in two-parts on CBC in Canada and as one two hour movie on ABC in the USA. Nominated for several Emmy awards, it follows Hyde on a series of sexual conquests and hack and slash murders, finally shot by "Devlin" (as Utterson is renamed).

- 1971, movie UK, Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde. Directed by Roy Ward Baker, starring Ralph Bates as Jekyll and Martine Beswick as Hyde. The earliest work to show Jekyll transform into a woman. Recasts Jekyll as Jack the Ripper, who uses Sister Hyde as a convenient disguise to carry out his murders.

- 1971, movie UK, I, Monster. Directed by Stephen Weeks, starring Christopher Lee in the Jekyll/Hyde role and Peter Cushing as Utterson. Recasts Jekyll (with a name change to Dr Marlowe/Mr Blake) as a 1906 Freudian psychotherapist. Retains a fair amount of Stevenson's original plot and dialogue.

- 1972, movie Spain, Dr. Jekyll y el Hombre Lobo, a Paul Naschy film in his long-running series pits Dr. Jekyll against a werewolf.

- 1973, movie U.S., directed by David Winters. A musical version made for television with original music by Lionel Bart starring Kirk Douglas as Jekyll/Hyde, with co-stars Michael Redgrave as Danvers, Stanley Holloway as Poole and Donald Pleasance as Fred Smudge. Nominated for Emmy award (Outstanding Achievement in Music Direction of a Variety, Musical or Dramatic Program - Irwin Kostal {music director})

- 1981, TV UK, with David Hemmings in the dual role and directed by Alastair Reid. This version gives a twist to the usual ending when Jekyll's body turns into Mr Hyde upon his death.

- 1989, movie U.S., Edge Of Sanity, a low-budget remake with Anthony Perkins as a Jekyll whose experiments with synthetic cocaine transform him into Hyde, who is also Jack The Ripper.

- 1989, NES Video game published by Bandai.

- 1989, TV UK, with Laura Dern and Anthony Andrews in the dual role. This version, adapted by Babylon 5 creator J. Michael Straczynski, was similar to Hammer's 1960 version in that Mr Hyde is the more physically attractive of the two; Dr Jekyll is depicted as a shy, mousy asocial scientist & Hyde is a handsome sociopath.

- 1990, TV U.S., Jekyll & Hyde, a four-hour, two-part, made-for-television film starring Michael Caine in the title roles, added a final twist by having Jekyll impregnate his sweetheart (played by Cheryl Ladd) with a baby that is revealed to look just like Hyde.

- 1991, Stage play, opened in London. Written by David Edgar for the Royal Shakespeare Company. The play is notable for its fidelity to the book's plot, though it invents a sister for Jekyll.

- 1995, movie U.S., Dr. Jekyll and Ms. Hyde, in which a descendant of Dr. Jekyll creates a variant of his ancestor's potion that turns him into a woman.

- 1996, movie U.S., Mary Reilly. Directed by Stephen Frears. Starring Julia Roberts and John Malkovich and based on the 1990 novel Mary Reilly by Valerie Martin, a re-working of Stevenson's plot centered around a maid in Jekyll's household named Mary Reilly.

- 1997, Musical U.S. Jekyll & Hyde. Music by Frank Wildhorn, book and lyrics by Leslie Bricusse. Originally conceived for the stage by Steve Cuden and Frank Wildhorn. This musical features the song "This Is The Moment" and attracted a devoted cult following.

- 2002, TV Movie UK Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde starring John Hannah as both characters, with body language and wardrobe the only distinction between the appearance of the two. The narrative is chronologically disjointed, beginning with the end of the story then returning to the beginning via narrated flashbacks with the occasional brief glimpse of the reading of Jekyll's confession by Utterson

- 2006, Canadian film Jekyll + Hyde Directed by Nick Stillwell. Starring Bryan Fisher as Henry "j" Jekyll and Bree Turner as Utterson. Two medical students set out to create a new drug derived from ecstacy that would enhance and change their personalities. Distributed in Canada by MAPLE PICTURES.

- 2007, TV serial UK, Jekyll. A 6 part BBC serial, aired from June 16th 2007, starring James Nesbitt as Tom Jackman, a modern Jekyll whose Hyde wreaks havoc amongst modern day London. Jackman's transformation into Hyde is triggered by an as yet unknown cause, but it is not from a potion as it is in the book. Hyde is also credited as a completely new personality rather than the dark side of Jackman, with Hyde calling Jackman 'daddy'. The serial is not an adaptation of Stevenson's book, but rather a continuation taking place in the present day: the original book and both Dr Jekyll and Stevenson are prominently featured within the story.

References

- ^ Stevenson published the book as Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (without "The"), for reasons unknown, but it has been supposed to increase the "strangeness" of the case (Richard Drury (2005)). Later publishers added "The" to make it grammatically correct, but it was not the author's original intent. The story is often known today simply as Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde or even Jekyll and Hyde.

- ^ (IPA: [ˈdʒiːkəl]) is the correct Scots pronunciation of the name, but (IPA: [ˈdʒɛkəl]) remains an accepted and common pronunciation.

- ^ Swearingen, Roger G. The Prose Writings of Robert Louis Stevenson. London: Macmillan, 1980. (ISBN) p. 37.

- ^ Nightmare: Birth of Victorian Horror (TV series) Jekyll and Hyde (1996)

- ^ Nightmare: Birth of Victorian Horror (TV series) Jekyll and Hyde (1996)

- ^ For an overview of contemporary theories, see Lisa Butler, "“that damned old business of the war in the members”: The Discourse of (In)Temperance in Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde", in Romanticism on the Net, Issue 44, November 2006

- ^ Nightmare: Birth of Victorian Horror (TV series) Jekyll and Hyde (1996)

- Richard Dury. The Robert Louis Stevenson website.

- Richard Dury, ed. (2005). The Annotated Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. ISBN 88-7544-030-1, over 80 pages of introduction material, extensive annotation notes, 40 pages of derivative works and extensive bibliography.

- Paul M. Gahlinger, M.D., Ph.D. (2001). Illegal Drugs: A Complete Guide to their History, Chemistry, Use, and Abuse. Sagebrush Medical Guide. Pg 41. ISBN 0-9703130-1-2.

- Kathrine Linehan, ed. (2003). Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Norton Critical Edition, contains extensive annotations, contextual essays and criticisms. ISBN 0-393-97465-0

- Warlock was Dr Jekyll prototype BBC News

- Borinskikh L.I. (1990c). ‘The method to reveal a character in the works of R.L.Stevenson [The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde]’/. In *** (ed.) The Problem of character in literature. Tchelyabinsk: Tchelyabinsk State University. Pp. 31-32. [in Russian, German and Hindi].

External links

- The Annotated 'Strange Case Of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde', an annotated version at Wikisource.

- Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde[1] from Internet Archive. Many antiquarian illustrated editions.

- The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde at Project Gutenberg ver.1

- The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde at Project Gutenberg ver.2

- Free audiobook download of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde from LibriVox.

- Noe, Denise (2007). "The Strange Case of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde". Men's News Daily, 12 Feb. 2007.

- Jekyll & Hyde: The Musical. Official Website