Outlaw: Difference between revisions

SilvonenBot (talk | contribs) m robot Adding: fi:Lainsuojaton |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 144: | Line 144: | ||

===Spanish=== |

===Spanish=== |

||

* [[Perot Rocaguinarda]], [[Catalan people|Catalan]] bandit |

* [[Perot Rocaguinarda]], [[Catalan people|Catalan]] bandit |

||

* [[Sanchicorrota]], [[Navarre]] late Middle Age bandit |

|||

* [[El Tempranillo]], [[Andalusia]]n'' bandolero'' |

* [[El Tempranillo]], [[Andalusia]]n'' bandolero'' |

||

* [[El Pernales]], [[Andalusia]]n'' bandolero'' |

* [[El Pernales]], [[Andalusia]]n'' bandolero'' |

||

Revision as of 07:18, 19 June 2008

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2007) |

An outlaw or bandit is a person living the lifestyle of outlawry; the word literally means "outside the law",[1] by folk-etymology from the original meaning "laid outside" of the Old Norse word útlagi, from which the word outlaw was borrowed into English.[2] In the common law of England, a judgment declaring someone an outlaw, known as a "Writ of Outlawry", was one of the harshest penalties in the legal system, since the outlaw could not use the legal system to protect himself if needed, such as from mob justice.[3]

Though the judgment of outlawry is now obsolete (even though it inspired the pro forma Outlawries Bill which is still to this day introduced in the British House of Commons during the State Opening of Parliament), romanticised outlaws became stock characters in several fictional settings, particularly in Western movies. Thus, "outlaw" is still commonly used to mean those violating the law[4] or, by extension, those living that lifestyle, whether actual criminals evading the law or those merely opposed to "law-and-order" notions of conformity and authority (such as the "outlaw country" music movement in the 1970s).

A feature of older legal systems

In British common law, an outlaw was a person who had defied the laws of the realm, by such acts as ignoring a summons to court, or fleeing instead of appearing to plead when charged with a crime. In the earlier law of Anglo-Saxon England, outlawry was also declared when a person committed a homicide and could not pay the weregild, the blood-money, due to the victim's kin. Outlawry also existed in other legal codes of the time, such as the ancient Norse and Icelandic legal code. These societies did not have any police force or prisons and criminal sentences were therefore restricted to either fines or outlawry.

To be declared an outlaw was to suffer a form of civil or social[5] death. The outlaw was debarred from all civilized society. No one was allowed to give him food, shelter, or any other sort of support — to do so was to commit the crime of aiding and abetting, and to be in danger of the ban oneself. An outlaw might be killed with impunity; and it was not only lawful but meritorious to kill a thief flying from justice — to do so was not murder. A man who slew a thief was expected to declare the fact without delay, otherwise the dead man’s kindred might clear his name by their oath and require the slayer to pay weregild as for a true man[6] Because the outlaw has defied civil society, that society was quit of any obligations to the outlaw —outlaws had no civil rights, could not sue in any court on any cause of action, though they were themselves personally liable.

In the context of criminal law, outlawry faded not so much by legal changes as by the greater population density of the country, which made it harder for wanted fugitives to evade capture; and by the international adoption of extradition pacts. In the civil context, outlawry became obsolescent in civil procedure by reforms that no longer required summoned defendants to appear and plead. Still, the possibility of being declared an outlaw for derelictions of civil duty continued to exist in English law until 1879 and in Scots law until the late 1940s. The Third Reich made extensive use of the concept.[7] Prior to the Nuremberg Trials, the British jurist Lord Chancellor Lord Simon attempted to resurrect the concept of outlawry in order to provide for summary executions of captured Nazi war criminals. Although Simon's point of view was supported by Winston Churchill, American and Soviet attorneys insisted on a trial, and he was thus overruled..

Hobsbawm's Bandits

The colloquial sense of an outlaw as bandit or brigand is the subject of a colourful monograph by Eric Hobsbawm[8]. According to Hobsbawm

The point about social bandits is that they are peasant outlaws whom the lord and state regard as criminals, but who remain within peasant society, and are considered by their people as heroes, as champions, avengers, fighters for justice, perhaps even leaders of liberation, and in any case as men to be admired, helped and supported. This relation between the ordinary peasant and the rebel, outlaw and robber is what makes social banditry interesting and significant...........Social banditry of this kind is one of the most universal social phenomena known to history.

Hobsbawm's book discusses the bandit as a symbol, and mediated idea, and many of the outlaws he refers to, such as Ned Kelly, Mr. Dick Turpin, and Billy the Kid, are also listed below..

Famous outlaws

The stereotype owes a great deal to English folklore precedents, in the tales of Robin Hood and of gallant highwaymen. But outlawry was once a term of art in the law, and one of the harshest judgments that could be pronounced on anyone's head.

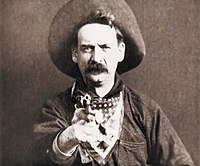

The outlaw is familiar to contemporary readers as an archetype in Western movies, depicting the lawless expansionism period of the United States in the late 19th century. The Western outlaw is typically a criminal who operates from a base in the wilderness, and opposes, attacks or disrupts the fragile institutions of new settlements. By the time of the Western frontier, many jurisdictions had abolished the process of outlawry, and the term was used in its more popular meaning.

American Western

- Joaquin Murietta

- The Sundance Kid

- William Quantrill

- Jim Miller

- Sam Bass

- Kid Curry

- Butch Cassidy

- Billy the Kid

- Jesse James

- Frank James

- Cole Younger

- Marlow Brothers

- Belle Starr

- Black Jack

- Black Bart

- John Daly

- Tiburcio Vasquez

- Reno Gang

American Great Depression

Argentinian

Australian

- Jackson Mullane

- Ned Kelly

- Martin Cash

- Ben Hall

- Frank Gardiner

- Captain Thunderbolt

- Dan Morgan

- Jack the Rammer

- Mary Ann Bugg

- Moondyne Joe

- William Westwood aka Jackey Jackey

British

- John Nevison - 17th century highwayman[9]

- Dick Turpin - 18th century highwayman

- James MacLaine - Scottish highwayman

- Tom King - English highwayman

- Sawney Beane - Scottish outlaw

- Edgar the Outlaw - English king

- Robin Hood - Legendary Medieval English outlaw

- Eustace Folville - English outlaw and soldier

- Adam the Leper - Fourteenth-century English gang-leader

- William Wallace - Leader of the Scottish resistance to Edward I.

- Rob Roy MacGregor - Scottish Chieftain.

- Twm Siôn Cati - Welsh Outlaw from Tregaron in Tudor times, ended up mayor of Brecon

- James Hind - 17th century highwayman

- John Clavell - English highwayman, author, and lawyer

- Claude Duval - French-born highwayman in England

East Asian

- Zhang Xianzhong - nicknamed Yellow Tiger, was a Chinese bandit and rebel leader who conquered Sichuan Province in the middle of the 17th century.

- Song Jiang - Historical Chinese outlaw immortalised in the classic Water Margin

- Hong Gildong - Historical/legendary Korean outlaw

- Ishikawa Goemon - Legendary Japanese thief featured in kabuki plays

- Nezumi Kozō - Japanese thief

- Wong Fei Hung - Famous Chinese herbalist considered an outlaw hero in Chinese folklore

Irish

Italian

- Marco Sciarra - famous Neapolitan brigand chief

- Rinaldo Rinaldini - Italian outlaw/ folk hero

- Salvatore Giuliano - Sicilian bandit/ separatist

- Giuseppe Musolino - Italian outlaw/ folk hero

Middle Eastern and Indian

- Fudayl ibn Iyad - famous highwayman of Khurasan who repented and traveled in search of knowledge. He is revered by Muslims as a major figure of early Sufism.

- Ya'qub-i Laith Saffari - rose from a bandit to the rule of much of modern Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan

- Nirushan Neela - famous Bandit of southern Asia who was never caught by police. Stopped killing in 1930 and was never heard from again.

Punjabi

- Dulla Bhatti - was a Punjabi who led a rebellion against the Mughal emperor Akbar. His act of helping a poor peasant's daughter to get married led to a famous folk take which is still recited every year on the festival of Lohri by Punjabis.

Tamil

- Veerappan, Poacher, Sandalwood smuggler, India

Canadian

German

- Eppelein von Gailingen

- Johannes Bückler, nicknamed Schinderhannes

- Lips Tullian

- Nickel List

- Matthias Klostermayr, aka Bavarian Hiasl, aka Hiasl of Bavaria, aka der Bayerische Hiasl, aka da Boarische Hiasl

Russian

- Nightingale the Robber - myth

- Yermak Timofeyevich - 16th century Cossack outlaw and explorer

- Stenka Razin - Cossack leader

- Joseph Stalin - led "fighting squads" in bank robberies to raise funds for the Bolshevik Party.

Spanish

- Perot Rocaguinarda, Catalan bandit

- Sanchicorrota, Navarre late Middle Age bandit

- El Tempranillo, Andalusian bandolero

- El Pernales, Andalusian bandolero

Turkish

- İnce Memed, a legendary fictional character by Yaşar Kemal

- Atçalı Kel Mehmet Efe, an outlaw who led a local revolt against Ottoman Empire

- Çakırcalı Mehmet Efe, one of the most powerful outlaws of late Ottoman era

New Zealander

- James Mckenzie Shepherd, drover, sheep rustler [1]

- Te Kooti Maori warrior & leader

Serbian

Others

- Phoolan Devi

- Lampião (Brazil)

- Jack the Robber (Roma)

- Juraj Jánošík (Slovakia)

- Václav Babinský (Czech outlaw)

- Johann Georg Grasel (Moravia)

- Sobri Jóska (Hungarian highwayman)

- Louis Dominique Cartouche (famous French bandit)

- Heraclio Bernal (Mexican bandit)

- Cercyon (Greek), a bandit killed by Theseus

- Kassa Hailu, later Emperor Tewodros II of Ethiopia

- Napoleon by the coalition in Vienna

- When the government of the First Spanish Republic was unable to reduce the Cantonalist rebellion centered in Cartagena, Spain, the Cartagena fleet was declared piratic, allowing any nation to prey on it.

- Toño Bicicleta (Bicycle Tony), A notorious bicycle-riding Puerto Rican criminal who became an element of local folklore.

- Martin Luther was declared an outlaw by the Diet of Worms

- Nelson Mandela

- Fictional character, Bernard Mickey Wrangle, in Tom_Robbins' book Still Life with Woodpecker, considers himself an outlaw, rather than a criminal.

See also

- Vigilante

- Robbery

- Robber baron

- Pirate

- Buccaneer

- Highwayman

- Hajduk

- Uskoks

- Brigandage

- Outlaw motorcycle club

- Social bandits, a term invented by Eric Hobsbawm

- Shanlin

- Thug

- Dacoit

- Feud

- Mafia

- Gangs

- Klepht

References

- ^ Black's Law Dictionary at 1255 (4th ed. 1951), citing 22 Viner, Abr. 316.

- ^ Sara M. Pons-Sanz, Norse-Derived Vocabulary in Late Old English Texts: Wulfstan's Works, a Case Study, North-Western European Language Evolution, Supplement, 22 (Odense: University Press of Southern Denmark, 2007), p. 80.

- ^ Black's Law Dictionary at 1255 (4th ed. 1951), and citations therein.

- ^ Black's Law Dictionary at 1255 (4th ed. 1951), citing Oliveros v. Henderson, 116 S.C. 77, 106 S.E. 855, 859.

- ^ Zygmunt Bauman, "Modernity and Holocaust".

- ^ F. Pollock and F. W. Maitland, The History of English Law Before the Time of Edward I (1895, 2nd. ed., Cambridge, 1898, reprinted 1968).

- ^ Shirer,"The Third Reich."

- ^ Bandits, E J Hobsbawm, pelican 1972

- ^ BBC Inside Out - Highwaymen