STS-125: Difference between revisions

m →Media: this is pretty obvious, nobody would think someone would be using a laptop during an EVA - clarified statement to make that clear |

→Contingency mission: m change of tense. MJD. |

||

| Line 176: | Line 176: | ||

{{main|STS-400}} |

{{main|STS-400}} |

||

Due to the inclination and other orbit parameters of Hubble, ''Atlantis'' would be unable to use the [[International Space Station]] as a "safe haven" in the event of structural or mechanical failure.<ref name="move">{{Cite web|url=http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2006/05/hubble-servicing-mission-moves-up/|title=Hubble Servicing Mission moves up|accessdate=October 16 2007|dateformat=mdy|publisher=NASASpaceflight.com|year=2007|author=Chris Bergin}}</ref><ref name="rescue">{{Cite web|url=http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2006/07/nasa-evaluates-rescue-options-for-hubble-mission/|title=NASA Evaluates Rescue Options for Hubble Mission|accessdate=October 16 2007|dateformat=mdy|publisher=NASASpaceflight.com|year=2007|author=John Copella}}</ref> [[STS-400]] is the flight designation given to the [[Contingency Shuttle Crew Support]] mission which would be launched in the event ''Atlantis'' becomes disabled during STS-125.<ref name="conting">{{cite news | first=Chris | last=Bergin | coauthors= | title=NASA sets new launch date targets through to STS-124 | date=2007-04-15 | publisher=NASASpaceflight | url =http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2007/04/nasa-sets-new-launch-date-targets-through-to-sts-124/ | work = | pages = | accessdate = 2007-08-21}}</ref> To preserve NASA's post-''Columbia'' requirement of having shuttle rescue capability, a second shuttle |

Due to the inclination and other orbit parameters of Hubble, ''Atlantis'' would be unable to use the [[International Space Station]] as a "safe haven" in the event of structural or mechanical failure.<ref name="move">{{Cite web|url=http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2006/05/hubble-servicing-mission-moves-up/|title=Hubble Servicing Mission moves up|accessdate=October 16 2007|dateformat=mdy|publisher=NASASpaceflight.com|year=2007|author=Chris Bergin}}</ref><ref name="rescue">{{Cite web|url=http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2006/07/nasa-evaluates-rescue-options-for-hubble-mission/|title=NASA Evaluates Rescue Options for Hubble Mission|accessdate=October 16 2007|dateformat=mdy|publisher=NASASpaceflight.com|year=2007|author=John Copella}}</ref> [[STS-400]] is the flight designation given to the [[Contingency Shuttle Crew Support]] mission which would be launched in the event ''Atlantis'' becomes disabled during STS-125.<ref name="conting">{{cite news | first=Chris | last=Bergin | coauthors= | title=NASA sets new launch date targets through to STS-124 | date=2007-04-15 | publisher=NASASpaceflight | url =http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2007/04/nasa-sets-new-launch-date-targets-through-to-sts-124/ | work = | pages = | accessdate = 2007-08-21}}</ref> To preserve NASA's post-''Columbia'' requirement of having shuttle rescue capability, a second shuttle was on launch pad 39-B at the time of STS-125's launch. This imposed a constraint on deactivation and conversion of pad 39B for [[Ares I]] flight tests. NASA investigated whether it would be possible to use the same pad to launch both STS-125 and STS-400.<ref name="singlepad">{{Cite web|url=http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2009/01/sts-125400-single-pad-option-progress-protect-ares-i-x/|title=STS-125/400 Single Pad option progress|accessdate=2009-05-11|publisher=NASA Spaceflight.com|year=January 19, 2009|author=Chris Bergin}}</ref> Much of the conversion work at LC-39B was completed while the pad was still available for the shuttle, including the installation of three lightning towers, and the removal of crane equipment and a lightning rod from the top of the [[Fixed Service Structure]]. |

||

NASA has had [[STS-3xx|contingency]] rescue missions on standby for all nine flights conducted between the fatal ''Columbia'' flight and STS-125. |

NASA has had [[STS-3xx|contingency]] rescue missions on standby for all nine flights conducted between the fatal ''Columbia'' flight and STS-125. |

||

Revision as of 10:05, 13 May 2009

This article documents a current or recent spaceflight. Details may change as the mission progresses. Initial news reports may be unreliable. The last updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. For more information please see WikiProject Spaceflight. |

| COSPAR ID | 2009-025A |

|---|---|

| SATCAT no. | 34933 |

| |

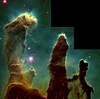

STS-125, or HST-SM4 (Hubble Space Telescope Servicing Mission 4) is the current space shuttle mission and the fifth and final servicing mission to the Hubble Space Telescope (HST).[3] Launch occurred on May 11, 2009 at 2:01 p.m. EDT.[2][4][5] The mission is being flown by Space Shuttle Atlantis, with another shuttle, Space Shuttle Endeavour, ready to launch in case a rescue mission is needed. Due to an anomaly aboard the telescope that occurred on September 27, 2008, STS-125 was delayed until May 2009 to prepare a second data handling unit replacement for the telescope.[6][7][8] Atlantis is carrying two new instruments to the HST, a replacement Fine Guidance Sensor, and six new gyroscopes and batteries to allow the telescope to continue to function at least through 2014.[3] The crew will also install a new thermal blanket layer to provide improved insulation, and a "soft-capture mechanism" to aid in the safe de-orbiting of the telescope by an unmanned spacecraft at the end of its operational lifespan.

The mission is the 30th flight of Space Shuttle Atlantis, the first flight of Atlantis since STS-122, and the first flight of Atlantis not to visit a space station since STS-66 in 1994.[2][9] It is the only shuttle mission since the Columbia accident to not visit the International Space Station.[2]

Due to the difference between the orbit of the International Space Station, and that of the HST, Atlantis will be unable to reach the ISS in the event of its heat shield becoming damaged upon launch. Therefore space shuttle Endeavour is ready on launch pad 39B for immediate flight on the STS-400 Launch On Need (LON) rescue mission throughout STS-125 should the need arise.

Crew

- Scott D. Altman (4) - Commander

- Gregory C. Johnson (1) - Pilot

- Michael T. Good (1) - Mission Specialist 1

- K. Megan McArthur (1) - Mission Specialist 2

- John M. Grunsfeld (5) - Mission Specialist 3

- Michael J. Massimino (2) - Mission Specialist 4

- Andrew J. Feustel (1) - Mission Specialist 5

Number in parentheses indicates number of spaceflights by each individual prior to and including this mission.

Crew notes

The crew of STS-125 includes three astronauts who have previous experience with servicing Hubble.[10][11] Altman visited Hubble as commander of STS-109, the fourth Hubble servicing mission, in 2002. Grunsfeld, an astronomer, has serviced Hubble twice, performing a total of five spacewalks on STS-103 in 1999, and STS-109. Massimino served with both Altman and Grunsfeld on STS-109, and performed two spacewalks to service the telescope.

Mission parameters

- Mass: TBD

- Perigee: 486 km

- Apogee: 578 km

- Inclination/Altitude: 28.5° at 304 nautical miles[11]

- Period: 97 min

Mission payloads

STS-125 will carry the "Soft-Capture Mechanism" and install it onto the telescope.[12] This will enable a spacecraft to be sent to the telescope to assist in its safe de-orbit at the end of its life. It is a circular mechanism containing structures and targets to aid docking.[10]

The mission will add two new instruments to Hubble. The first instrument, the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph, will be the most sensitive ultraviolet spectrograph installed on the telescope.[10][13] Its far-UV channel will be 30 times more sensitive than previous instruments and the near-UV will be twice as sensitive. The second instrument, the Wide Field Camera 3, is a panchromatic wide-field camera that can record a wide range of wavelengths, including infrared, visible, and ultraviolet light.[10]

The infrastructure of the telescope will be maintained and upgraded by replacing a "Fine Guidance Sensor" that controls the telescope's directional system, installing a set of six new gyroscopes, replacing batteries, and installing a new outer blanket layer to provide improved insulation.[10]

The payload bay elements are the Super Lightweight Interchangeable Carrier (SLIC) holding the Wide Field Camera 3, new batteries, and a radiator; the ORU Carrier with the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph and FGS-3R instruments; the Flight Support Structure (FSS) for holding the Hubble during repairs; and the Multi-Use Lightweight Equipment Carrier (MULE) holding support equipment.

Along with the collectible items that are flown on shuttle missions, such as mission patches, flags, and other personal items for the crew, is an official Harlem Globetrotters basketball, as well as a basketball that Edwin Hubble used in 1909 when he played for the University of Chicago.[14][15] Once the mission returns to Earth, the Harlem Globetrotters basketball will be placed in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, and Hubble's ball will be returned to the University of Chicago.[14]

IMAX movie

At the end of September, 2007, Warner Bros. Pictures and IMAX Corporation announced that in cooperation with NASA, an IMAX 3D camera will travel to the Hubble telescope in the payload bay of Atlantis for production of a new film that will chronicle the story of the Hubble telescope.[13] IMAX has made a number of movies centered around space, including Destiny in Space, The Dream Is Alive, Mission to Mir, Blue Planet, Magnificent Desolation: Walking on the Moon 3D, and the first trip of IMAX to the ISS in 2001, to make Space Station 3D.[13][16]

Media

Astronaut Michael J. Massimino has been using twitter to document the training and preparations for the mission. He mentioned that he would like to try sending twitter updates from space during his off-duty time.[17]

Mission background

The mission marks:[9]

- 157th American manned space flight

- 126th shuttle mission since STS-1

- 30th Flight of Atlantis

- 101st post-Challenger mission

- 13th post-Columbia mission

STS-125 was originally scheduled to be ISS assembly mission ISS-1J. The mission would have delivered the Kibo Japanese Experiment Module (JEM) and JEM's specialized Remote Manipulator System to the station. Columbia was originally planned to fly the fifth Hubble mission, as Columbia was not the optimum orbiter for ISS assembly due to the weight of the orbiter.

STS-125 will be the first visit to the Hubble Space Telescope for Atlantis; the telescope has been previously serviced twice by Discovery, and once each by Columbia and Endeavour.

Shuttle processing

Following the Columbia accident review, the Return to Flight missions, and the reinstatement of the Hubble repair mission, STS-125 was assigned to Discovery, with a launch date no earlier than May 2008.[18] This originally moved the mission ahead of STS-119, ISS Assembly flight 15A.

The crew of Atlantis went to the Kennedy Space Center for the Crew Equipment Interface Test in early July, 2008. This allowed the STS-125 crew to get familiar with the orbiter and the hardware they would be using during the flight.

Launch delays

On August 22, 2008, after a delay following Tropical Storm Fay, Atlantis was rolled from the Orbiter Processing Facility to the Vehicle Assembly Building, where it was mated to the external fuel tank and solid rocket booster stack. Problems encountered during the mating process, and delays due to Hurricane Hanna delayed rollout to the pad, which is normally done seven days after rollover.[19][20]

STS-125 was further delayed to October 2008 due to manufacturing delays on external tanks for future space shuttle missions. Lockheed Martin experienced delays during the production changes to make new external tanks with all the enhancements recommended by the Columbia Accident Investigation Board, making it impossible for them to produce two tanks for the STS-125 mission—one for Atlantis, and one for Endeavour for an emergency rescue mission, if necessary—in time for the original August launch date.[21]

The first rollout to Launch Pad 39A occurred on September 4, 2008. On 27 September 2008, the Science Instrument Command and Data Handling (SIC&DH) Unit on the Hubble Space Telescope failed.[3] Because of its importance, NASA postponed the launch of STS-125 on September 29, 2008 until 2009 so the failed unit could be replaced as well.[3] Atlantis was rolled back to the Vehicle Assembly Building on October 20, 2008.

On October 30, 2008, NASA announced that Atlantis would be removed from its solid rocket boosters & external tank stack and sent back to its Orbiter Processing Facility to await a targeted launch time at 1:11 p.m. EDT on May 12, 2009.[6] The stack was turned over to be used on the STS-119 mission instead. On March 23, 2009 Atlantis was mated to its new stack in the Vehicle Assembly Building. Roll-out to launch Pad 39A took place on March 31, 2009.[22]

On April 24, 2009, NASA managers issued a change request to move the STS-125 launch up one day to May 11, 2009 at 2:01 pm EDT. The change was made official at the flight readiness review on April 30, 2009.[23] The reason cited for the change was to add one more day to the launch window from 2 to 3 days. The shuttle process flow schedule was adjusted to support this change.[23]

Mission timeline

May 11 (Flight day 1, Launch)

Following a smooth countdown, Atlantis launched on time, at 2:01 p.m. EDT.[2][4] Almost immediately after launch and during the ascent, flight systems reported problems with a hydrogen tank transducer and a circuit breaker; the crew was immediately advised to disregard the resultant alarms and continue to orbit.[24] During the post-launch news conference, NASA managers said the initial early review of the launch video showed no obvious debris events, but a thorough analysis would be performed to ensure the orbiter sustained no significant damage during ascent.[25] After working through their post launch checklists, the crew opened the payload bay doors, deployed the Ku band antenna, and moved into the robotic activities portion of the day, which included a survey of the payload bay and crew cabin survey with the orbiter's robotic arm.[26][25]

During the post-launch inspection of Pad 39A, a twenty five foot area on the north side of the flame deflector was found to have damage where some of the heat resistant coating came off.[27] Following the launch of STS-124, severe damage was seen at the pad where bricks were blasted from the walls, but NASA officials stated the damage from the STS-125 launch was not nearly as severe and should not impact the launch of STS-127 in June.[27]

May 12 (Flight day 2)

Following the morning wake up call, the crew set right to work on the day's tasks, which were centered around inspection of the orbiter's heat shield. Using the shuttle robotic arm and the Orbiter Boom Sensor System (OBSS), the crew went through a detailed inspection of the orbiter's tile and Reinforced carbon-carbon surfaces. During the inspection, engineers on the ground noticed a small area of tile on the forward area of the shuttle's right wing that appeared to have suffered some damage during ascent.[28][29] Mission managers called up to the crew to alert them of the find, noting that one of the orbiter's wing leading edge sensors recorded a debris event during ascent, around 104 - 106 seconds following liftoff, which may have been the cause of the damage seen in that area.[29] CAPCOM Dan Burbank advised the crew that the damage did not initially appear to be serious, but assured the crew that the image analysis team would be reviewing the imagery further, and engineers on the ground would be analyzing it to determine if a focused inspection would be required.[29]

As part of the Flight Day 2 Execute Package, ground engineers also provided further information on the circuit breaker failure seen at launch.[30] The breaker, (Channel 1 Aerosurfaces, ASA 1) is part of the shuttle's Flight Control Systems (FCS), a subsystem of the Guidance, Navigation and Control (GNC) systems. The failure would have no impact to the mission due to redundant systems.[30]

In addition to the survey of the orbiter's heat shield, the crew gathered and inspected the EVA tools and spacesuits that would be used for the mission's spacewalks, and prepared the Flight Support System (FSS) for berthing with Hubble on flight day three.[31]

Extra-vehicular activity

Five back-to-back EVAs are planned:[26][32]

| EVA # | Spacewalkers | Start (UTC) | End (UTC) | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVA 1 |

John M. Grunsfeld Andrew J. Feustel |

May 14 TBD |

May 14 TBD |

Planned: 6 hours, 30 minutes |

| Planned: Replacement of a Wide Field Camera, replace a failed science data processing computer, and install a mechanism for spacecraft to capture Hubble for de-orbit at the end of the telescope's life (Soft Capture Mechanism). | ||||

| EVA 2 |

Michael J. Massimino Michael T. Good |

May 15 TBD |

May 15 TBD |

Planned: 6 hours, 30 minutes |

| Planned: Change out three boxes that each contains two of the telescope's six gyroscopes, and change out the first battery module (three batteries). | ||||

| EVA 3 |

Grunsfeld Feustel |

May 16 TBD |

May 16 TBD |

Planned: 6 hours, 30 minutes |

| Planned: Installation of the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph and repair of the Advanced Camera for Surveys. | ||||

| EVA 4 |

Massimino Good |

May 17 TBD |

May 17 TBD |

Planned: 6 hours, 30 minutes |

| Planned: Repair and upgrade of the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph, and installation of a stainless steel exterior blanket for insulation. | ||||

| EVA 5 |

Grunsfeld Feustel |

May 18 TBD |

May 18 TBD |

Planned: 5 hours, 45 minutes |

| Planned: Installation of Fine Guidance Sensor No. 3, installation of an additional exterior insulation blanket, and replacement of the final battery module. | ||||

Wake-up calls

A tradition for NASA human spaceflights since the days of Gemini is that mission crews are played a special musical track at the start of each day in space. Each track is specially chosen, often by their families, and usually has a special meaning to an individual member of the crew, or is applicable to their daily activities.[33][34]

Flight Day 2: "Kryptonite" performed by 3 Doors Down, played for Greg Johnson. WAV MP3 TRANSCRIPT

Contingency mission

Due to the inclination and other orbit parameters of Hubble, Atlantis would be unable to use the International Space Station as a "safe haven" in the event of structural or mechanical failure.[18][35] STS-400 is the flight designation given to the Contingency Shuttle Crew Support mission which would be launched in the event Atlantis becomes disabled during STS-125.[36] To preserve NASA's post-Columbia requirement of having shuttle rescue capability, a second shuttle was on launch pad 39-B at the time of STS-125's launch. This imposed a constraint on deactivation and conversion of pad 39B for Ares I flight tests. NASA investigated whether it would be possible to use the same pad to launch both STS-125 and STS-400.[37] Much of the conversion work at LC-39B was completed while the pad was still available for the shuttle, including the installation of three lightning towers, and the removal of crane equipment and a lightning rod from the top of the Fixed Service Structure.

NASA has had contingency rescue missions on standby for all nine flights conducted between the fatal Columbia flight and STS-125.

See also

- 2009 in spaceflight

- Space Shuttle program

- List of space shuttle missions

- List of spacewalks and moonwalks

- List of human spaceflights chronologically

References

- ^ NASA (May 11, 2009). "STS-125 MCC Status Report #01". NASA. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b c d e William Harwood for CBS News (May 11, 2009). "Final servicing mission begins to extend Hubble's life". Spaceflightnow.com. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b c d John Zarrella (May 11, 2009). "Shuttle blasts off for final Hubble fix". CNN. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b Associated Press (May 11, 2009). "Shuttle blasts off on Hubble mission". USA Today. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Dennis Overbye (May 11, 2009). "Atlantis Mission Offers One Last Lifeline to Hubble". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b NASA (2008). "NASA Managers Delay Hubble Servicing Mission". NASA. Retrieved October 31 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Dennis Overbye (2008). "NASA Delays Trip to Repair Hubble Telescope". New York Times. Retrieved September 29 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Marcia Dunn - Associated Press (2008). "NASA Delays Repair Mission to Hubble Telescope". ABC News. Retrieved November 14 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ a b William Harwood (April 28, 2009). "STS-125 Quick-Look". CBS News.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b c d e NASA (2007). "NASA Approves Mission and Names Crew for Return to Hubble". NASA. Retrieved October 16 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ a b NASA (2007). "STS-125: Final Shuttle Mission to Hubble Space Telescope". NASA. Retrieved October 16 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ NASA (2008). "The Soft Capture and Rendezvous System". NASA. Retrieved October 25 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ a b c NASA (2007). "IMAX Camera Returns to Space to Chronicle Hubble Space Telescope". NASA. Retrieved October 16 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ a b Harlem Globetrotters News. "Outer Space Next Stop for Trotters" (May 7, 2009). Harlem Globetrotters.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Anne Minard. "Unusual Cargo Headed to Hubble: A Basketball?" (May 11, 2009). Universe Today.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ IMAX (2008). "IMAX - All Films". IMAX Corporation. Retrieved October 25 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Sharon Gaudin (April 23, 2009). "NASA astronaut says he will Twitter from space". Computerworld Inc. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b Chris Bergin (2007). "Hubble Servicing Mission moves up". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved October 16 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Spaceflight Now.com (2008). "Hurricane Hanna delays shuttle's move to pad". Spaceflight Now.com. Retrieved September 2 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Frank Moring, Jr. (2008). "Hurricane Chances Postpone Atlantis Rollout". Aviation Week. Retrieved September 2 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ William Harwood (2008). "Hubble servicing mission's launch date threatened". [CBS News]. Retrieved March 28 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Lisa Cilli (March 31, 2009). "Atlantis Rolls To Launch Pad Ahead Of May Launch". CBS Television. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b Chris Bergin (April 24, 2009). "Shuttle managers decide to advance STS-125 launch target to May 11". NASA Spaceflight.com. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Tariq Malik (May 11, 2009). "Space Shuttle Launches to Save Hubble Telescope". Space.com.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accesdate=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b William Harwood (May 11, 2009). "Shuttle in good shape after launch; no signs of impact damage; initial post-launch inspections on tap". CBS News. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b NASA (May 5, 2009). "STS-125 Press Kit" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b William Harwood for CBS News (May 12, 2009). "Pad flame deflector damaged during Atlantis launch". Spaceflightnow.com.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ LeRoy Cain (May 12, 2009). "STS-125 Post-Mission Management Team Briefing Materials". NASA.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b c William Harwood for CBS News (May 12, 2009). "Minor tile damage found during Atlantis inspections". Spaceflightnow.com.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b NASA Flight Activities Officer (FAO) (May 11, 2009). "STS-125 FD 02 Execute Package" (PDF). nasa.gov.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accesdate=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ NASA (May 12, 2009). "STS-125 MCC Status Report #02". NASA.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Tony Ceccacci (May 5, 2009). "STS-125 Mission Overview Briefing Materials". NASA. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Fries, Colin (2007-06-25). "Chronology of Wakeup Calls" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ NASA (2009). "STS-125 Wakeup Calls". NASA. Retrieved May 11 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ John Copella (2007). "NASA Evaluates Rescue Options for Hubble Mission". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved October 16 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Bergin, Chris (2007-04-15). "NASA sets new launch date targets through to STS-124". NASASpaceflight. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Chris Bergin (January 19, 2009). "STS-125/400 Single Pad option progress". NASA Spaceflight.com. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link)