Pyramid scheme: Difference between revisions

Grammar correction. |

minor |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

[[Pyramid]] schemes are illegal in many countries including [[Albania]], [[Australia]],<ref>[http://www.comlaw.gov.au/comlaw/Legislation/Act1.nsf/0/5A0DC6C047FFEA5ACA256F72000F75F1/$file/1282002.pdf Trade Practices Amendment Act (No. 1) 2002] ''Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) ss 65AAA - 65AAE, 75AZO</ref> [[Brazil]], [[Bulgaria]], [[Canada]], [[People's Republic of China|China]],<ref name="Regulations for the Prohibition of Pyramid Sales">[http://tradeinservices.mofcom.gov.cn/en/b/2005-08-23/24294.shtml Regulations for the Prohibition of Pyramid Sales]</ref> [[Colombia]],<ref>http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/7736124.stm</ref> [[France]], [[Germany]], [[Hungary]], [[Iceland]]{{Citation needed|date=August 2009}}, [[Iran]]<ref>[http://www.presstv.ir/detail.aspx?id=113056§ionid=3510212 Key GoldQuest members arrested in Iran Airport]</ref>, [[Italy]],<ref>[http://www.parlamento.it/parlam/leggi/05173l.htm Legge 17 agosto 2005, n. 173] (in Italian)</ref> [[Japan]],<ref>[http://law.e-gov.go.jp/htmldata/S53/S53HO101.html 無限連鎖講の防止に関する法律] (in Japanese)</ref> [[Malaysia]], [[Mexico]], [[Nepal]]{{Citation needed|date=March 2008}}, [[Netherlands|The Netherlands]],<ref name="Sentence by the High Council of the Netherlands regarding a pyramid scheme">[http://zoeken.rechtspraak.nl/resultpage.aspx?snelzoeken=true&searchtype=ljn&ljn=AR8424&u_ljn=AR8424 Sentence by the High Council of the Netherlands regarding a pyramid scheme]</ref> [[New Zealand]],<ref>[http://www.consumerfraudreporting.org/pyramidschemes_laws.htm Laws and Regulations Covering Multi-Level Marketing Programs and Pyramid Schemes] ''Consumer Fraud Reporting.com''</ref> [[Norway]]<ref>http://www.lovdata.no/all/tl-19950224-011-004.html#16</ref>, the [[Philippines]],<ref>[http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C05E4DA1539F933A05750C0A9659C8B63] Investors in Philippine Pyramid Scheme Lose over $2 Billion</ref> [[Poland]], [[Portugal]], [[Romania]],<ref>[http://www.ziua.ro/display.php?data=2006-07-12&id=203369 Explozia piramidelor] ''Ziarul Ziua, 12.07.2006''</ref> [[South Africa]],<ref>[http://www.whitecollarcrime.co.za/news.php?item.95] Pyramid Schemes</ref> [[Sri Lanka]],<ref>[http://www.documents.gov.lk/Acts/2006/Banking%20(Amendment)%20Act%20No.%2015%20of%202006/Banking%20(Amendment)%20Act%20(E).pdf Pyramid Schemes Illegal Under Section 83c of the Banking Act of Sri Lanka]Department of Government Printing, Sri Lanka</ref> [[Switzerland]], [[Thailand]],<ref name="สมาคมการขายตรงไทย">[http://www.tdsa.org/download/piramid.pdf ข้อมูลเพิ่มเติมในระบบธุรกิจขายตรงและธุรกิจพีระมิด] by Thai Direct Selling Association (in Thai)</ref> the [[United Kingdom]], and the [[United States]].<ref>[http://www.ftc.gov/speeches/other/dvimf16.shtm Pyramid Schemes] ''Debra A. Valentine, General Counsel, Federal Trade Commission''</ref> |

[[Pyramid]] schemes are illegal in many countries including [[Albania]], [[Australia]],<ref>[http://www.comlaw.gov.au/comlaw/Legislation/Act1.nsf/0/5A0DC6C047FFEA5ACA256F72000F75F1/$file/1282002.pdf Trade Practices Amendment Act (No. 1) 2002] ''Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) ss 65AAA - 65AAE, 75AZO</ref> [[Brazil]], [[Bulgaria]], [[Canada]], [[People's Republic of China|China]],<ref name="Regulations for the Prohibition of Pyramid Sales">[http://tradeinservices.mofcom.gov.cn/en/b/2005-08-23/24294.shtml Regulations for the Prohibition of Pyramid Sales]</ref> [[Colombia]],<ref>http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/7736124.stm</ref> [[France]], [[Germany]], [[Hungary]], [[Iceland]]{{Citation needed|date=August 2009}}, [[Iran]]<ref>[http://www.presstv.ir/detail.aspx?id=113056§ionid=3510212 Key GoldQuest members arrested in Iran Airport]</ref>, [[Italy]],<ref>[http://www.parlamento.it/parlam/leggi/05173l.htm Legge 17 agosto 2005, n. 173] (in Italian)</ref> [[Japan]],<ref>[http://law.e-gov.go.jp/htmldata/S53/S53HO101.html 無限連鎖講の防止に関する法律] (in Japanese)</ref> [[Malaysia]], [[Mexico]], [[Nepal]]{{Citation needed|date=March 2008}}, [[Netherlands|The Netherlands]],<ref name="Sentence by the High Council of the Netherlands regarding a pyramid scheme">[http://zoeken.rechtspraak.nl/resultpage.aspx?snelzoeken=true&searchtype=ljn&ljn=AR8424&u_ljn=AR8424 Sentence by the High Council of the Netherlands regarding a pyramid scheme]</ref> [[New Zealand]],<ref>[http://www.consumerfraudreporting.org/pyramidschemes_laws.htm Laws and Regulations Covering Multi-Level Marketing Programs and Pyramid Schemes] ''Consumer Fraud Reporting.com''</ref> [[Norway]]<ref>http://www.lovdata.no/all/tl-19950224-011-004.html#16</ref>, the [[Philippines]],<ref>[http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C05E4DA1539F933A05750C0A9659C8B63] Investors in Philippine Pyramid Scheme Lose over $2 Billion</ref> [[Poland]], [[Portugal]], [[Romania]],<ref>[http://www.ziua.ro/display.php?data=2006-07-12&id=203369 Explozia piramidelor] ''Ziarul Ziua, 12.07.2006''</ref> [[South Africa]],<ref>[http://www.whitecollarcrime.co.za/news.php?item.95] Pyramid Schemes</ref> [[Sri Lanka]],<ref>[http://www.documents.gov.lk/Acts/2006/Banking%20(Amendment)%20Act%20No.%2015%20of%202006/Banking%20(Amendment)%20Act%20(E).pdf Pyramid Schemes Illegal Under Section 83c of the Banking Act of Sri Lanka]Department of Government Printing, Sri Lanka</ref> [[Switzerland]], [[Thailand]],<ref name="สมาคมการขายตรงไทย">[http://www.tdsa.org/download/piramid.pdf ข้อมูลเพิ่มเติมในระบบธุรกิจขายตรงและธุรกิจพีระมิด] by Thai Direct Selling Association (in Thai)</ref> the [[United Kingdom]], and the [[United States]].<ref>[http://www.ftc.gov/speeches/other/dvimf16.shtm Pyramid Schemes] ''Debra A. Valentine, General Counsel, Federal Trade Commission''</ref> |

||

These types of schemes have existed for at least a century some with variations to hide their true nature and there are people who hold that multilevel marketing even if it is legal is nothing more than a pyramid scheme.<ref>{{cite book |

These types of schemes have existed for at least a century some with variations to hide their true nature and there are people who hold that multilevel marketing, even if it is legal, is nothing more than a pyramid scheme.<ref>{{cite book |

||

| last = Carroll |

| last = Carroll |

||

| first = Robert Todd |

| first = Robert Todd |

||

Revision as of 06:01, 25 February 2010

A pyramid scheme is a non-sustainable business model that involves the exchange of money primarily for enrolling other people into the scheme, often without any product or service being delivered. Pyramid schemes are a form of fraud.

Pyramid schemes are illegal in many countries including Albania, Australia,[1] Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, China,[2] Colombia,[3] France, Germany, Hungary, Iceland[citation needed], Iran[4], Italy,[5] Japan,[6] Malaysia, Mexico, Nepal[citation needed], The Netherlands,[7] New Zealand,[8] Norway[9], the Philippines,[10] Poland, Portugal, Romania,[11] South Africa,[12] Sri Lanka,[13] Switzerland, Thailand,[14] the United Kingdom, and the United States.[15]

These types of schemes have existed for at least a century some with variations to hide their true nature and there are people who hold that multilevel marketing, even if it is legal, is nothing more than a pyramid scheme.[16][17][18][19]

Concept and basic models

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

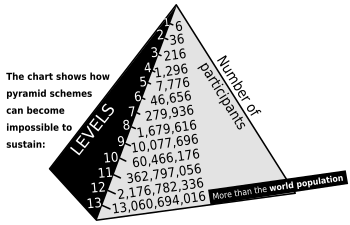

A successful pyramid scheme combines a fake yet seemingly credible business with a simple-to-understand yet sophisticated-sounding money-making formula which is used for profit. The essential idea is that the mark, Mr. X, makes only one payment. To start earning, Mr. X has to recruit others like him who will also make one payment each. Mr. X gets paid out of receipts from those new recruits. They then go on to recruit others. As each new recruit makes a payment, Mr. X gets a cut. He is thus promised exponential benefits as the "business" expands.

Such "businesses" seldom involve sales of real products or services to which a monetary value might be easily attached. However, sometimes the "payment" itself may be a non-cash valuable. To enhance credibility, most such scams are well equipped with fake referrals, testimonials, and information. The flaw is that there is no end benefit. The money simply travels up the chain. Only the originator (sometimes called the "pharaoh") and a very few at the top levels of the pyramid make significant amounts of money. The amounts dwindle steeply down the pyramid slopes. Individuals at the bottom of the pyramid (those who subscribed to the plan, but were not able to recruit any followers themselves) end up with a deficit.

The "Eight-Ball" model

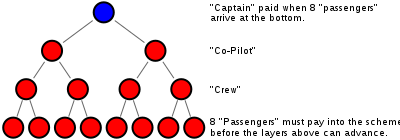

Many pyramids are more sophisticated than the simple model. These recognize that recruiting a large number of others into a scheme can be difficult so a seemingly simpler model is used. In this model each person must recruit two others, but the ease of achieving this is offset because the depth required to recoup any money also increases. The scheme requires a person to recruit two others, who must each recruit two others, who must each recruit two others.

Prior instances of this scam have been called the "Airplane Game" and the four tiers labelled as "captain," "co-pilot," "crew," and "passenger" to denote a person's level. Another instance was called the "Original Dinner Party" which labelled the tiers as "dessert," "main course," "side salad," and "appetizer." A person on the "dessert" course is the one at the top of the tree. Another variant, "Treasure Traders," variously used gemology terms such as "polishers," "stone cutters," etc. or gems like "rubies," "sapphires," "diamonds," etc.

Such schemes may try to downplay their pyramid nature by referring to themselves as "gifting circles" with money being "gifted." Popular scams such as the "Women Empowering Women"[20] do exactly this. Joiners may even be told that "gifting" is a way to skirt around tax laws.

Whichever euphemism is used, there are 15 total people in four tiers (1 + 2 + 4 + 8) in the scheme - with the Airplane Game as the example, the person at the top of this tree is the "captain," the two below are "co-pilots," the four below are "crew," and the bottom eight joiners are the "passengers."

The eight passengers must each pay (or "gift") a sum (e.g. $1000) to join the scheme. This sum (e.g. $8000) goes to the captain who leaves, with everyone remaining moving up one tier. There are now two new captains so the group splits in two with each group requiring eight new passengers. A person who joins the scheme as a passenger will not see a return until they exit the scheme as a captain. This requires that 14 others have been persuaded to join underneath them.

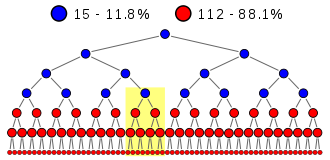

Therefore, the bottom 3 tiers of the pyramid always lose their money when the scheme finally collapses. Consider a pyramid consisting of tiers with 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64 members. The highlighted section corresponds to the previous diagram.

If the scheme collapses at this point, only those in the 1, 2, 4, and 8 got out with a return. The remainder in the 16, 32, and 64 tier lose everything. 112 out of the total 127 members or 88% lost all of their money.

During a wave of pyramid activity, a surge frequently develops once a significant fraction of people know someone personally who exited with a $8000 payout for example. This spurs others to seek to get in on one of the many pyramids before the wave collapses.

The figures also hide the fact that the confidence trickster would make the lion's share of the money. They would do this by filling in the first 3 tiers (with 1, 2, and 4 people) with phoney names, ensuring they get the first 7 payouts, at 8 times the buy-in sum, without paying a single penny themselves. So if the buy-in were $1000, they would receive $56,000, paid for by the first 56 investors. They would continue to buy in underneath the real investors, and promote and prolong the scheme for as long as possible in order to allow them to skim even more from it before the collapse.

Other cons may also be effective. For example, rather than using false names, a group of seven people may agree to form the top three layers of a pyramid without investing any money. They then work to recruit eight paying passengers, and pretend to follow the pyramid payout rules, but in reality split any money received. Ironically, though they are being conned, the eight paying passengers are not really getting anything less for their money than if they were buying into a "legitimate" pyramid which had split off from a parent pyramid. They truly are now in a valid pyramid, and have the same opportunity to earn a windfall if they can successfully recruit enough new members and reach captain. This highlights the fact that by "buying" in to a pyramid, passengers are not really obtaining anything of value they could not create themselves other than a vague sense of "legitimacy" or history of the pyramid, which may make it marginally easier to sell passenger seats below them.

Matrix schemes

Matrix schemes use the same fraudulent non-sustainable system as a pyramid; here, the participants pay to join a waiting list for a desirable product which only a fraction of them can ever receive. Since matrix schemes follow the same laws of geometric progression as pyramids, they are subsequently as doomed to collapse. Such schemes operate as a queue, where the person at head of the queue receives an item such as a television, games console, digital camcorder, etc. when a certain number of new people join the end of the queue. For example ten joiners may be required for the person at the front to receive their item and leave the queue. Each joiner is required to buy an expensive but potentially worthless item, such as an e-book, for their position in the queue. The scheme organizer profits because the income from joiners far exceeds the cost of sending out the item to the person at the front. Organizers can further profit by starting a scheme with a queue with shill names that must be cleared out before genuine people get to the front. The scheme collapses when no more people are willing to join the queue. Schemes may not reveal, or may attempt to exaggerate, a prospective joiner's queue position which essentially means the scheme is a lottery. Some countries have ruled that matrix schemes are illegal on that basis.

Connection to multi-level marketing

The network marketing or multi-level marketing business has become associated with pyramid schemes as "Some schemes may purport to sell a product, but they often simply use the product to hide their pyramid structure." [21] and the fact while some people call MLMs in general "pyramid selling"[22][23][24][25][26] others use the term to denote an illegal pyramid scheme masquerading as an MLM.

While the FTC provides guidelines for determining whether an organization is a legal MLM or an illegal pyramid scheme (such as: 1) substantial sales of products or services to end users, 2) commissions paid only on product usage, not on new enrollments, 3) company buys back the inventory of terminating participants, and 4) if the product has inherent value for its standard price. [27]), some believe MLMs in general are nothing more than legalized pyramid schemes[28][29][30][31] making the issue of a particular MLM being legal or not moot.

Notable recent cases

The Malaysian SwissCashTM

Swiss Mutual Fund originally mentioned on its website that it was created after World War II in 1948 by the Cheviot family of France, with operations based in Berne, Switzerland. After 48 years (1996), the firm moved to the Commonwealth of Dominica due to changes in financial regulations in Europe. However the Swiss Embassy in Kuala Lumpur has stated the following:

"The Swiss Mutual Fund (1948) and or Swiss Cash are not registered companies in Switzerland. Until proof of the contrary, the Embassy doubts that the remarks about these funds and their historic links to Switzerland as outlined on their original website are genuine. The original website is indeed registered in the USA and the contact telephone number is from New Jersey (USA)."

This information was also corroborated by the Swiss Embassy in Singapore. On December 13 2006, Swiss Mutual Fund (1948) S.A. was struck off the Commonwealth of Dominica's Register of International Business Companies. The current version of the Swiss Mutual Fund website no longer includes any information about the company's history. At June 2007, the Securities Commission, Malaysia's capital markets regulator, has already taken action against the promoters of Swiss Cash. The website went offline on August 27, members could not log into the website. According to internet rumours, the website was down due to a hurricane, and would be back on 25 Aug. It did not come back online on August 25. Afterward, few similar websites were up. But no official announcement from Swiss Mutual Fund proved whether those websites were from Swiss Mutual Fund. Those websites only had a front page, and could not be logged into. Internet rumors said website down was due to upgrade and maintainence, and would be back at 1 Sep 2007. Nothing happened on 1 Sep. Internet rumors said Swiss Mutual Fund would be back on 15 Sep 07. Nothing happened on 15 Sep. On Sept 17, the Financial Supervision Commission of the Commonwealth of Dominica released a press release which confirms that Swisscash is not a registered or incorporated company and does not have any established business in the island nation.

Internet

In 2003, the United States Federal Trade Commission (FTC) disclosed what it called an internet-based "pyramid scam." Its complaint states that customers would pay a registration fee to join a program that called itself an "internet mall" and purchase a package of goods and services such as internet mail, and that the company offered "significant commissions" to consumers who purchased and resold the package. The FTC alleged that the company's program was instead and in reality a pyramid scheme that did not disclose that most consumers's money would be kept, and that it gave affiliates material that allowed them to scam others.[32]

Others

In early 2006 Ireland was hit by a wave of schemes with major activity in Cork and Galway. Participants were asked to contribute €20,000 each to a "Liberty" scheme which followed the classic eight-ball model. Payments were made in Munich, Germany to skirt Irish tax laws concerning gifts. Spin-off schemes called "Speedball" and "People in Profit" prompted a number of violent incidents and calls were made by politicians to tighten existing legislation.[33] Ireland has launched a website to better educate consumers to pyramid schemes and other scams.[34]

On November 12, 2008 riots broke out in the municipalities of Pasto, Tumaco, Popayan and Santander de Quilichao, Colombia after the collapse of several pyramid schemes. Thousands of victims had invested their money in pyramids that promised them extraordinary interest rates. The lack of regulation laws allowed those pyramids to grow excessively during several years. Finally, after the riots the Colombian government was forced to declare the country in economical emergency in order to seize and stop those schemes. Several of the pyramid's managers were arrested, and these are being prosecuted for the crime of "illegal massive money reception."[35]

November 2008: The Kyiv Post reported on November 26, 2008 that American citizen Robert Fletcher (Robert T. Fletcher III; aka "Rob") was arrested by the SBU (Ukraine State Police) after being accused by Ukrainian investors of running a Ponzi scheme and associated pyramid scam netting $20 million in US dollars. (The Kiev Post also reports that some estimates are as high as $150M USD.)

See also

- Advanced fee fraud

- Autosurf

- BurnLounge

- Cobra Group (company)

- High-yield investment program

- Holiday Magic

- Make Money Fast

- Multi-level marketing

- Ponzi scheme - A similar type of fraud, which involves making payment to a central originator, who pays returns to investors from their own money or money paid by subsequent investors, rather than from any actual profit earned.

- Primerica

- Sali Berisha

- Success University

References

- ^ Trade Practices Amendment Act (No. 1) 2002 Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) ss 65AAA - 65AAE, 75AZO

- ^ Regulations for the Prohibition of Pyramid Sales

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/7736124.stm

- ^ Key GoldQuest members arrested in Iran Airport

- ^ Legge 17 agosto 2005, n. 173 (in Italian)

- ^ 無限連鎖講の防止に関する法律 (in Japanese)

- ^ Sentence by the High Council of the Netherlands regarding a pyramid scheme

- ^ Laws and Regulations Covering Multi-Level Marketing Programs and Pyramid Schemes Consumer Fraud Reporting.com

- ^ http://www.lovdata.no/all/tl-19950224-011-004.html#16

- ^ [1] Investors in Philippine Pyramid Scheme Lose over $2 Billion

- ^ Explozia piramidelor Ziarul Ziua, 12.07.2006

- ^ [2] Pyramid Schemes

- ^ Pyramid Schemes Illegal Under Section 83c of the Banking Act of Sri LankaDepartment of Government Printing, Sri Lanka

- ^ ข้อมูลเพิ่มเติมในระบบธุรกิจขายตรงและธุรกิจพีระมิด by Thai Direct Selling Association (in Thai)

- ^ Pyramid Schemes Debra A. Valentine, General Counsel, Federal Trade Commission

- ^ Carroll, Robert Todd (2003). The Skeptic's Dictionary: A Collection of Strange Beliefs, Amusing Deceptions, and Dangerous Delusions. Wiley. p. 235. ISBN 0471272426.

- ^ Coenen, Tracy (2009). Expert Fraud Investigation: A Step-by-Step Guide. Wiley. p. 168. ISBN 0470387963.

- ^ Ogunjobi, Timi (2008). SCAMS - and how to protect yourself from them. Tee Publishing. pp. 13–19.

- ^ Salinger (Editor), Lawrence M. (2005). Encyclopedia of White-Collar & Corporate Crime. Vol. 2. Sage Publishing. p. 880. ISBN 0761930043.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Pyramid selling scam that preys on women to be banned

- ^ Pyramid Schemes, May 13, 1998" Federal Trade Commission

- ^ Edwards, Paul (1997). Franchising & licensing: two powerful ways to grow your business in any economy. Tarcher. p. 356. ISBN 0874778980.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Clegg, Brian (2000). The invisible customer: strategies for successive customer service down the wire. Kogan Page. p. 112. ISBN 074943144X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Higgs, Philip (2007). Rethinking Our World. Juta Academic. p. 30. ISBN 0702172553.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kitching, Trevor (2001). Purchasing scams and how to avoid them. Gower Publishing Company. p. 4. ISBN 0566082810.

- ^ Mendelsohn, Martin (2004). The guide to franchising. Cengage Learning Business Press. p. 36. ISBN 1844801624.

- ^ Facts for Consumers; Multilevel Marketing Plans Federal Trade Commission

- ^ Carroll, Robert Todd (2003). The Skeptic's Dictionary: A Collection of Strange Beliefs, Amusing Deceptions, and Dangerous Delusions. Wiley. p. 235. ISBN 0471272426.

- ^ Coenen, Tracy (2009). Expert Fraud Investigation: A Step-by-Step Guide. Wiley. p. 168. ISBN 0470387963.

- ^ Ogunjobi, Timi (2008). SCAMS - and how to protect yourself from them. Tee Publishing. pp. 13–19.

- ^ Salinger (Editor), Lawrence M. (2005). Encyclopedia of White-Collar & Corporate Crime. Vol. 2. Sage Publishing. p. 880. ISBN 0761930043.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ FTC Charges Internet Mall Is a Pyramid Scam Federal Trade Commission

- ^ Gardaí hold firearm after pyramid scheme incident Irish Examiner

- ^ National Consumer Agency Ireland

- ^ Colombians riot over pyramid scam. Colombia: BBC news. Nov 13, 2008.

- The Fraudsters - How Con Artists Steal Your Money Chapter 9, Pyramids of Sand (ISBN 978-1-903582-82-4) by Eamon Dillon, published September 2008 by Merlin Publishing, Ireland

External links

- An information graphic that describes a pyramid scheme

- FTC consumer complaint form

- Article by Financial Crimes Investigator, Bill E. Branscum

- Spoof article

- The Math Behind Pyramid Schemes, Chain Letters, and 2-Up Schemes - Investigates the mathematics of the geometric series involved.

- IMF feature on "The Rise and Fall of Albania's Pyramid Schemes"

- Cockeyed.com presents: Pyramid Schemes - A description of the 8-ball model and matrix schemes which is a close cousin to pyramid schemes.

- National Consumer Agency on Pyramid Schemes - Irish consumer site describes two local pyramid schemes and offers advice to would-be participants.

- PyramidSim.com simulation, graphing and calculation of various pyramid schemes.

- National Consumer Agency Ireland

- Australian Trade Practices Amendment Act (No. 1) 2002 Australian Law Online

- Public Warning on Pyramid Schemes Central Bank of Sri Lanka