Abydos, Egypt: Difference between revisions

m →Cult Centre: Lower case |

Corrected link to Pharaoh |

||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

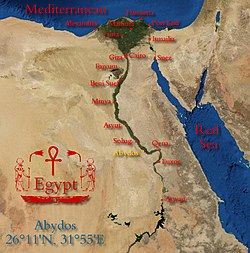

'''Abydos''' ([[Egyptian language|Egyptian]] '''Abdju''', '''''3b<u>d</u>w''''', [[Manuel de Codage|MdC]]: ''AbDw''; {{lang-ar|<big>أبيدوس</big>}}, {{Lang-el|Άβυδος}}), one of the most ancient cities of [[Upper and Lower Egypt|Upper Egypt]], is about 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) west of the [[Nile]] at latitude 26° 10' N. The Egyptian name of both the eighth [[Nome (Egypt)|Nome]] of [[Upper Egypt]] and its capital city was Abdju, technically, ''3b<u>d</u>w'', as in the hieroglyphs shown to the right, '''''the hill of the symbol or reliquary''''', in which the sacred head of [[Osiris]] was preserved. The Greeks named it [[Abydos, Hellespont|Abydos]], after their city on the [[Hellespont]]; the modern [[Arabic language|Arabic]] name is [[el-'Araba el Madfuna]] ({{lang-ar|العربة المدفونة}} ''al-ʿarabah al-madfunah''). |

'''Abydos''' ([[Egyptian language|Egyptian]] '''Abdju''', '''''3b<u>d</u>w''''', [[Manuel de Codage|MdC]]: ''AbDw''; {{lang-ar|<big>أبيدوس</big>}}, {{Lang-el|Άβυδος}}), one of the most ancient cities of [[Upper and Lower Egypt|Upper Egypt]], is about 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) west of the [[Nile]] at latitude 26° 10' N. The Egyptian name of both the eighth [[Nome (Egypt)|Nome]] of [[Upper Egypt]] and its capital city was Abdju, technically, ''3b<u>d</u>w'', as in the hieroglyphs shown to the right, '''''the hill of the symbol or reliquary''''', in which the sacred head of [[Osiris]] was preserved. The Greeks named it [[Abydos, Hellespont|Abydos]], after their city on the [[Hellespont]]; the modern [[Arabic language|Arabic]] name is [[el-'Araba el Madfuna]] ({{lang-ar|العربة المدفونة}} ''al-ʿarabah al-madfunah''). |

||

Considered one of the most important archaeological sites of [[Ancient Egypt]] (near the town of [[al-Balyana]]), the sacred city of Abydos was the site of many ancient temples, including a [[Umm el-Qa'ab]], a royal [[necropolis]] where early [[pharaohs]] were entombed.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/abydos/abydoskingstombs.html |title=Tombs of kings of the First and Second Dynasty |accessdate=2008-01-15 |publisher=UCL |work=Digital Egypt}}</ref> These tombs began to be seen as extremely significant burials and in later times it became desirable to be buried in the area, leading to the growth of the town's importance as a cult site. |

Considered one of the most important archaeological sites of [[Ancient Egypt]] (near the town of [[al-Balyana]]), the sacred city of Abydos was the site of many ancient temples, including a [[Umm el-Qa'ab]], a royal [[necropolis]] where early [[pharaohs|Pharao]] were entombed.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/abydos/abydoskingstombs.html |title=Tombs of kings of the First and Second Dynasty |accessdate=2008-01-15 |publisher=UCL |work=Digital Egypt}}</ref> These tombs began to be seen as extremely significant burials and in later times it became desirable to be buried in the area, leading to the growth of the town's importance as a cult site. |

||

Today, Abydos is notable for the memorial temple of [[Seti I]], which contains an inscription from the nineteenth dynasty known to the modern world as the [[Abydos King List]]. It is a chronological list showing [[cartouche]]s of most dynastic [[pharaoh]]s of Egypt from [[Menes]] until [[Ramesses I]], Seti's father.<ref name=TEwjb>{{cite web |author=Misty Cryer |title=Travellers in Egypt - William John Bankes |year=2006 |work=TravellersinEgypt.org |url=http://www.travellersinegypt.org/archives/2004/10/william_john_bankes.html TravEgypt-WJB}}</ref> The Great Temple and most of the [[Kom el-Sultan|ancient town]] are buried under the modern buildings to the north of the Seti temple.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/abydos/abydostown.html|title=Abydos town |accessdate=2008-01-15 |publisher=UCL |work=Digital Egypt}}</ref> Many of the original structures and the artifacts within them are considered irretrievable and lost, many may have been destroyed by the new construction. |

Today, Abydos is notable for the memorial temple of [[Seti I]], which contains an inscription from the nineteenth dynasty known to the modern world as the [[Abydos King List]]. It is a chronological list showing [[cartouche]]s of most dynastic [[pharaoh]]s of Egypt from [[Menes]] until [[Ramesses I]], Seti's father.<ref name=TEwjb>{{cite web |author=Misty Cryer |title=Travellers in Egypt - William John Bankes |year=2006 |work=TravellersinEgypt.org |url=http://www.travellersinegypt.org/archives/2004/10/william_john_bankes.html TravEgypt-WJB}}</ref> The Great Temple and most of the [[Kom el-Sultan|ancient town]] are buried under the modern buildings to the north of the Seti temple.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/abydos/abydostown.html|title=Abydos town |accessdate=2008-01-15 |publisher=UCL |work=Digital Egypt}}</ref> Many of the original structures and the artifacts within them are considered irretrievable and lost, many may have been destroyed by the new construction. |

||

Revision as of 12:49, 26 February 2010

Abydos | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | +3 |

Abydos (Egyptian Abdju, 3bdw, MdC: AbDw; Arabic: أبيدوس, Greek: Άβυδος), one of the most ancient cities of Upper Egypt, is about 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) west of the Nile at latitude 26° 10' N. The Egyptian name of both the eighth Nome of Upper Egypt and its capital city was Abdju, technically, 3bdw, as in the hieroglyphs shown to the right, the hill of the symbol or reliquary, in which the sacred head of Osiris was preserved. The Greeks named it Abydos, after their city on the Hellespont; the modern Arabic name is el-'Araba el Madfuna (Arabic: العربة المدفونة al-ʿarabah al-madfunah).

Considered one of the most important archaeological sites of Ancient Egypt (near the town of al-Balyana), the sacred city of Abydos was the site of many ancient temples, including a Umm el-Qa'ab, a royal necropolis where early Pharao were entombed.[1] These tombs began to be seen as extremely significant burials and in later times it became desirable to be buried in the area, leading to the growth of the town's importance as a cult site.

Today, Abydos is notable for the memorial temple of Seti I, which contains an inscription from the nineteenth dynasty known to the modern world as the Abydos King List. It is a chronological list showing cartouches of most dynastic pharaohs of Egypt from Menes until Ramesses I, Seti's father.[2] The Great Temple and most of the ancient town are buried under the modern buildings to the north of the Seti temple.[3] Many of the original structures and the artifacts within them are considered irretrievable and lost, many may have been destroyed by the new construction.

History

| ||||

| Name of Abydos in hieroglyphs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Abydos was occupied by the rulers of the Predynastic period,[4] whose town, temple and tombs have been found there. The temple and town continued to be rebuilt at intervals down to the times of the thirtieth dynasty, and the cemetery was used continuously.

The pharaohs of the first dynasty were buried in Abydos, including Narmer, who is regarded as founder of the first dynasty, and his successor, Aha.[5] Some pharaohs of the second dynasty were also buried in Abydos. The temple was renewed and enlarged by these pharaohs as well. Funerary enclosures, misinterpreted in modern times as great 'forts', were built on the desert behind the town by three kings of the second dynasty; the most complete is that of Khasekhemwy.[6]

From the fifth dynasty, the deity Khentiamentiu, foremost of the Westerners, came to be seen as a manifestation of the dead pharaoh in the underworld. Pepi I (sixth dynasty) constructed a funerary chapel which evolved over the years into the Great Temple of Osiris, the ruins of which still exist within the town enclosure. Abydos became the centre of the worship of the Isis and Osiris cult.

During the First Intermediate Period, the principal deity of the area, Khentiamentiu, began to be seen as an aspect of Osiris, and the deities gradually merged and became regarded as one, with Osiris being assigned the epithet, Foremost of the Westerners. In the twelfth dynasty a gigantic tomb was cut into the rock by Senusret III. Associated with this tomb was a cenotaph, a cult temple and a small town known as Wah-Sut, that was used by the workers for these structures.[7]

The building during the eighteenth dynasty began with a large chapel of Ahmose I. Then Thutmose III built a far larger temple, about 130 × 200 ft (40 x 61 m). He also made a processional way leading past the side of the temple to the cemetery beyond, featuring a great gateway of granite.

Seti I, in the nineteenth dynasty, founded a temple to the south of the town in honor of the ancestral pharaohs of the early dynasties; this was finished by Ramesses II, who also built a lesser temple of his own. Merneptah added the Osireion just to the north of the temple of Seti.[7]

Ahmose II in the twenty-sixth dynasty rebuilt the temple again, and placed in it a large monolith shrine of red granite, finely wrought. The foundations of the successive temples were comprised within approximately 18 ft (5.5 m). depth of the ruins discovered in modern times; these needed the closest examination to discriminate the various buildings, and were recorded by more than 4000 measurements and 1000 levellings.[8]

The latest building was a new temple of Nectanebo I, built in the thirtieth dynasty. From the Ptolemaic times of the Greek occupancy of Egypt, that began three hundred years before the Roman occupancy that followed, the structure began to decay and no later works are known.[9]

Cult centre

From earliest times, Abydos was a cult centre, first of the local deity, Khentiamentiu, and from the end of the Old Kingdom, the rising cult of Osiris and Isis.

A tradition developed that the Early Dynastic cemetery was the burial place of Osiris and the tomb of Djer was reinterpreted as that of Osiris.

Decorations in tombs throughout Egypt, such as the one displayed to the right, record journeys to and from Abydos, as important pilgrimages made by individuals who were proud to have been able to make the important trip.

Major constructions

Great Osiris Temple

Successively from the first dynasty to the twenty-sixth dynasty, nine or ten temples were built on one site at Abydos. The first was an enclosure, about 30 × 50 ft (9 x 15 m), surrounded by a thin wall of unbaked bricks. Incorporating one wall of this first structure, the second temple of about 40 ft (12 m) square was built within a wall about 10 ft (3 m) thick. An outer temenos (enclosure) wall surrounded the grounds. This outer wall was thickened about the second or third dynasty. The old temple entirely vanished in the fourth dynasty, and a smaller building was erected behind it, enclosing a wide hearth of black ashes.

Pottery models of offerings are found in these ashes and probably were the substitutes for live sacrifices decreed by Khufu (or Cheops) in his temple reforms.

At an undetermined date, a great clearance of temple offerings had been made and a modern discovery of a chamber into which they were gathered has yielded the fine ivory carvings and the glazed figures and tiles that show the splendid work of the first dynasty. A vase of Menes with purple hieroglyphs inlaid into a green glaze and tiles with relief figures are the most important pieces found. The noble statuette of Cheops in ivory, found in the stone chamber of the temple, gives the only portrait of this great pharaoh.

The temple was rebuilt entirely on a larger scale by Pepi I in the sixth dynasty. He placed a great stone gateway to the temenos, an outer temenos wall and gateway, with a colonnade between the gates. His temple was about 40 × 50 ft (12 x 15 m) inside, with stone gateways front and back, showing that it was of the processional type. In the eleventh dynasty Mentuhotep I added a colonnade and altars. Soon after, Mentuhotep II entirely rebuilt the temple, laying a stone pavement over the area, about 45 ft (14 m) square, and added subsidiary chambers. Soon thereafter in the twelfth dynasty, Senusret I laid massive foundations of stone over the pavement of his predecessor. A great temenos was laid out enclosing a much larger area and the new temple itself was about three times the earlier size.

Temple of Seti

The temple of Seti I was built on entirely new ground half a mile to the south of the long series of temples just described. This surviving building is best known as the Great Temple of Abydos, being nearly complete and an impressive sight. A principal purpose of it was the adoration of the early pharaohs, whose cemetery, for which it forms a great funerary chapel, lies behind it. The long list of the pharaohs of the principal dynasties—recognized by Seti—are carved on a wall and known as the "Abydos King List" (showing the cartouche name of many dynastic pharaohs of Egypt from the first, Narmer or Menes, until his time)- with the exception of those noted above. There were significant names deliberately left out of the list. So rare as an almost complete list of pharaoh names, the Table of Abydos, re-discovered by William John Bankes, has been called the "Rosetta Stone" of Egyptian archaeology, analogous to the Rosetta Stone for Egyptian writing, beyond the Narmer Palette.[2]

There also were seven chapels built for the worship of the pharaoh and principal deities. At the back of the temple is an enigmatic structure known as The Osirion thought to be connected with the worship of Osiris (Caulfield, Temple of the Kings); and probably from those chambers led out the great Hypogeum for the celebration of the Osiris mysteries, built by Merenptah (Murray, The Osireion at Abydos). The temple was originally 550 ft (168 m) long, but the forecourts are scarcely recognizable, and the part still in good condition is about 250 ft (76 m) long and 350 ft (107 m) wide, including the wing at the side.

Except for the list of pharaohs and a panegyric on Ramesses II, the subjects are not historical, but mythological. The work is celebrated for its delicacy and artistic refinement, but lacks the life and character of that in earlier ages. The sculptures had been published mostly in hand copy, not facsimile, by Auguste Mariette in his Abydos, i.

Ramesses II temple

The adjacent temple of Ramesses II was much smaller and simpler in plan; but it had a fine historical series of scenes around the outside that lauded his achievements, of which the lower parts remain. The outside of the temple was decorated with scenes of the Battle of Kadesh. His list of pharaohs, similar to that of Seti I, formerly stood here; but the fragments were removed by the French consul and sold to the British Museum.

Tombs

The Royal necropolis of the earliest dynasties were placed about a mile into the great desert plain, in a place now known as Umm el-Qa'ab, The Mother of Pots, because of the shards remaining from all of the devotional objects left by religious pilgrims. The earliest burial is about 10×20 ft (3 x 6 m) inside, a pit lined with brick walls, and originally roofed with timber and matting. Others also built before Menes are 15×25 ft (4.6 x 7.6 m).

The probable tomb of Menes is of the latter size. Afterward the tombs increase in size and complexity. The tomb-pit is surrounded by chambers to hold offerings, the sepulchre being a great wooden chamber in the midst of the brick-lined pit. Rows of small pits, tombs for the servants of the pharaoh surround the royal chamber, many dozens of such burials being usual. Some of the offerings included sacrificed animals, such as the asses found in the tomb of Merneith. Evidence of human sacrifices exists in the early tombs, but this practice was changed into symbolic offerings later.

By the end of the second dynasty the type of tomb constructed changed to a long passage bordered with chambers on either side, the royal burial being in the middle of the length. The greatest of these tombs with its dependencies, covered a space of over 3,000 square kilometres (740,000 acres), however it is possible for this to be several tombs which have met in the making of a tomb; the Egyptians had no means of mapping the positioning of the tombs. The contents of the tombs have been nearly destroyed by successive plunderers; but enough remained to show that rich jewellery was placed on the mummies, a profusion of vases of hard and valuable stones from the royal table service stood about the body, the store-rooms were filled with great jars of wine, perfumed ointments, and other supplies, and tablets of ivory and of ebony were engraved with a record of the yearly annals of the reigns. The seals of various officials, of which over 200 varieties have been found, give an insight into the public arrangements.[10]

The cemetery of private persons began during the first dynasty with some pit-tombs in the town. It was extensive in the twelfth and thirteenth dynasties and contained many rich tombs. A large number of fine tombs were made in the eighteenth to twentieth dynasties, and members of later dynasties continued to bury their dead here until Roman times. Many hundreds of funeral steles were removed by Mariette's workmen, without any record of the burials being made.[11] Later excavations have been recorded by Edward R. Ayrton, Abydos, iii.; Maclver, El Amrah and Abydos; and Garstang, El Arabah.

"Forts"

Some of the tomb structures, referred to as "forts" by modern researchers, lay behind the town. Known as Shunet ez Zebib, it is about 450 × 250 ft (137 x 76 m) over all, and one still stands 30-ft (9 m) high. It was built by Khasekhemwy, the last pharaoh of the second dynasty. Another structure nearly as large adjoined it, and probably is older than that of Khasekhemwy. A third "fort" of a squarer form is now occupied by the Coptic convent; its age cannot be ascertained.[12]

Other

Some of the hieroglyphs on the site have been interpreted in certain esoteric mysticist and "ufological" circles as showing a helicopter, a battle tank or submarine, and a fighterplane or even a U.F.O., but these are commonly explained as the result of erosion and later adjustments to the original inscriptions. This concept was adopted in the plot of the Stargate series. [13][14][15]

See also

Notes

- ^ "Tombs of kings of the First and Second Dynasty". Digital Egypt. UCL. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- ^ a b Misty Cryer (2006). TravEgypt-WJB "Travellers in Egypt - William John Bankes". TravellersinEgypt.org.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) Cite error: The named reference "TEwjb" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ "Abydos town". Digital Egypt. UCL. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- ^ William Flinders Petrie, Abydos, ii. 64

- ^ Wilkinson (1999), p. 3

- ^ "The Funerary Enclosures of Abydos". Digitial Egypt. UCL. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- ^ a b Harvey, EA24, p.3

- ^ Petrie, Abydos, ii.

- ^ Petrie, Abydos, i. and ii.

- ^ Petrie, Royal Tombs, i. and ii.

- ^ Mariette, Abydos, ii. and iii.

- ^ Ayrton, Abydos, iii.

- ^ http://www.ufocom.org/pages/v_us/m_archeo/Abydos/abydos.html

- ^ http://www.catchpenny.org/abydos.html

- ^ http://members.tripod.com/~A_U_R_A/abydos.html

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

- Ayrton, Edward Russell (1904). Abydos. Vol. iii. Offices of the Egypt Exploration Fund.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Harvey, Stephen (Spring 2004). "New Evidence at Abydos for Ahmose's funerary cult". Egyptian Archaeology. 24. EES.

- Murray, Margaret Alice (1904). The Osireion at Abydos. Vol. ii. and iii. (reprint edition, June 1989 ed.). B. Quaritch. ISBN 1854170414.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (1999). Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge.

- Mariette, Auguste, Abydos, ii. and iii.

- William Flinders Petrie, Abydos, i. and ii.

- William Flinders Petrie, Royal Tombs, i. and ii.

External links

- "Abydos". Digital Egypt. UCL. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online, "Abydos" search: EncBrit-Abydos, importance of Abydos.

- The Mortuary Temple of Seti I at Abydos

- University of Pennsylvania Museum excavations at Abydos