Shroud of Turin: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

early history |

JimfromGTA (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 193: | Line 193: | ||

====Pollen grains==== |

====Pollen grains==== |

||

Researchers of the [[Hebrew University of Jerusalem]] reported the presence of [[pollen]] grains in the cloth samples, showing species appropriate to the spring in Israel. However, these researchers, [[Avinoam Danin]] and [[Uri Baruch]], were working with samples provided by [[Max Frei (criminologist)|Max Frei]], a Swiss police [[criminologist]] who had previously been censured for faking evidence. Independent review of the strands showed that one strand out of the 26 provided contained significantly more pollen than the others, perhaps pointing to deliberate contamination.<ref>Nickell, Joe: "Pollens on the 'shroud': A study in deception". ''Skeptical Inquirer'', Summer 1994., pp 379–385</ref> |

Researchers of the [[Hebrew University of Jerusalem]] reported the presence of [[pollen]] grains in the cloth samples, showing species appropriate to the spring in Israel. However, these researchers, [[Avinoam Danin]] and [[Uri Baruch]], were working with samples provided by [[Max Frei (criminologist)|Max Frei]], a Swiss police [[criminologist]] who had previously been censured for faking evidence. Independent review of the strands showed that one strand out of the 26 provided contained significantly more pollen than the others, perhaps pointing to deliberate contamination.<ref>Nickell, Joe: "Pollens on the 'shroud': A study in deception". ''Skeptical Inquirer'', Summer 1994., pp 379–385</ref>. (Note: there is NO proof that Max Fei faked any evidence in this particular situation). |

||

The Israeli researchers also detected the outlines of various flowering plants on the cloth, which they say would point to March or April and the environs of Jerusalem, based on the species identified. In the forehead area, corresponding to the crown of thorns if the image is genuine, they found traces of [[Gundelia tournefortii]], which is limited to this period of the year in the Jerusalem area. This analysis depends on interpretation of various patterns on the shroud as representing particular plants. Skeptics point out that the available [http://www.shroud.com/danin.htm images] cannot be seen as unequivocal support for any particular plant species due to the generally indistinct "blobiness", even under powerful microscopes, of these tiny, spotty impressions. |

The Israeli researchers also detected the outlines of various flowering plants on the cloth, which they say would point to March or April and the environs of Jerusalem, based on the species identified. In the forehead area, corresponding to the crown of thorns if the image is genuine, they found traces of [[Gundelia tournefortii]], which is limited to this period of the year in the Jerusalem area. This analysis depends on interpretation of various patterns on the shroud as representing particular plants. Skeptics point out that the available [http://www.shroud.com/danin.htm images] cannot be seen as unequivocal support for any particular plant species due to the generally indistinct "blobiness", even under powerful microscopes, of these tiny, spotty impressions. |

||

According to the author of The Resurrection of the Shroud, 45 of the 58 pollens found on the Shroud grow in Jerusalem. Additionally, pollen were found from six plants grown in Anatolia (Turkey) and the eastern Mediteranian. This physical evidence clearly establishes a linking of the Shroud to Jerusalem (78% of all pollen types) and to the middle east, including Edessa (circa AD 500) because of the pollen from Anatolia (page 111). |

|||

===Image analysis=== |

===Image analysis=== |

||

Revision as of 00:11, 24 March 2010

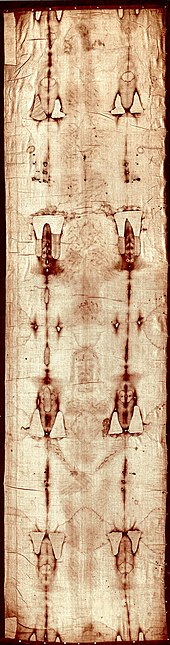

The Shroud of Turin (or Turin Shroud) is a linen cloth bearing the image of a man who appears to have suffered physical trauma in a manner consistent with crucifixion. It is kept in the royal chapel of the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin, northern Italy. The origins of the shroud and its image are the subject of intense debate among scientists, theologians, historians and researchers.

Some contend that the shroud is the cloth placed on the body of Jesus Christ at the time of his burial, and that the face image is the Holy Face of Jesus. Others contend that the artifact postdates the Crucifixion of Jesus by more than a millennium. Both sides of the argument use science and historical documents to make their case.

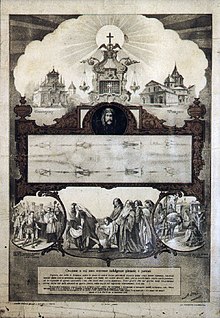

The image on the shroud is much clearer in black-and-white negative than in its natural sepia color. The striking negative image was first observed on the evening of May 28, 1898, on the reverse photographic plate of amateur photographer Secondo Pia, who was allowed to photograph it while it was being exhibited in the Turin Cathedral. The Catholic Church has neither formally endorsed nor rejected the shroud, but in 1958 Pope Pius XII approved of the image in association with the Roman Catholic devotion to the Holy Face of Jesus.

In 1978 a detailed examination was carried out by a team of American scientists called STURP. It found no reliable evidences of forgery. STURP called the question of how the image was formed "a mystery"[2]. In 1988 a radiocarbon dating test was performed on small samples of the shroud, concluding that they date from the Middle Ages, between 1260 CE and 1390 CE[3][4]. Controversy has arisen over the reliability of the test.[5][6][7]

Description

The shroud is rectangular, measuring approximately 4.4 × 1.1 m (14.3 × 3.7 ft). The cloth is woven in a three-to-one herringbone twill composed of flax fibrils. Its most distinctive characteristic is the faint, yellowish image of a front and back view of a naked man with his hands folded across his groin. The two views are aligned along the midplane of the body and point in opposite directions. The front and back views of the head nearly meet at the middle of the cloth.[8]

Reddish brown stains that have been said to include whole blood are found on the cloth, showing various wounds that, according to proponents, correlate with the yellowish image, the pathophysiology of crucifixion, and the Biblical description of the death of Jesus:[9] Markings on the lines include:[10]

- one wrist bears a large, round wound, claimed to be from piercing (the second wrist is hidden by the folding of the hands)

- upward gouge in the side penetrating into the thoracic cavity. Proponents claim this was a post-mortem event and there are separate components of red blood cells and serum draining from the lesion

- small punctures around the forehead and scalp

- scores of linear wounds on the torso and legs. Proponents claim that the wounds are consistent with the distinctive dumbbell wounds of a Roman flagrum.

- swelling of the face from severe beatings

- streams of blood down both arms. Proponents claim that the blood drippings from the main flow occurred in response to gravity at an angle that would occur during crucifixion

- no evidence of either leg being fractured

- large puncture wounds in the feet as if pierced by a single spike

The shroud includes images that are not easily distinguishable by the naked eye, and were first observed after the advent of photography. In May 1898 amateur Italian photographer Secondo Pia was allowed to photograph the shroud and he took the first photograph of the shroud on the evening of May 28, 1898. Pia was startled by the visible image of the negative plate in his darkroom. Negatives of the image give the appearance of a positive image, which implies that the shroud image is itself effectively a negative of some kind.[11] Pia was at first accused of doctoring his photographs, but was vindicated in 1931 when a professional photographer, Giuseppe Enrie, also photographed the shroud and his findings supported Pia's.[12]

The image of the "Man of the Shroud" has a beard, moustache, and shoulder-length hair parted in the middle. He is muscular and tall (various experts have measured him as from 1.75 m, or roughly 5 ft 9 in, to 1.88 m, or 6 ft 2 in).[13]

Fourteen large triangular patches and eight smaller ones were sewn onto the cloth by Poor Clare nuns to repair the damage from a fire in 1532 in the chapel in Chambery, France. Some burn holes and scorched areas down both sides of the linen are present, due to contact with molten silver during the fire that burned through it in places while it was folded.[14]

History

Archaeologist William Meacham states that of all religious relics, the history of the Shroud of Turin has generated the greatest controversy.[15] According to author Brian Haughton it is difficult to imagine a more controversial historical artifact, and that much of its history is obscure, with no historical record until the 16th century. Although prior historical references exist to some pieces of cloth with images, it is uncertain if these are the same as the shroud that is now in the Cathedral in Turin.[16] The Catholic Encyclopedia echoes the same sentiment: "A certain difficulty was caused by the existence elsewhere of other Shrouds similarly impressed with the figure of Jesus Christ."[17] However, the Catholic encyclopedia, as well as some other authors suggest that the recorded history traces back to the 14th century, but an origin date in the 15th century has also been suggested.[18][19][20]

The historical records for the shroud can be separated into three time periods: prior to the 14th century; from the 14th to the 16th century; and thereafter. Prior to the 14th century there are some congruent references like Pray Codex. The period from the 14th to the 16th century is subject to debate and controversy among historians. The history from the 16th century to the present is well understood (and uneventful except for two chapel fires), since the shroud has been housed in Turin Cathedral since then. As of the 17th century the shroud has been displayed (e.g. in the chapel built for that purpose by Guarino Guarini[21]) and in the 19th century it was first photographed during a public exhibition.[22]

There are no definite historical records concerning the shroud prior to the 14th century. Although there are numerous reports of Jesus' burial shroud, or an image of his head, of unknown origin, being venerated in various locations before the fourteenth century, there is no historical evidence that these refer to the shroud currently at Turin Cathedral.[23]

Historical records indicate that a shroud bearing an image of a crucified man existed in the small town of Lirey, France around the years 1353 to 1357. However, the correspondence of this shroud with the shroud in Turin, and its very origin has been debated by scholars and lay authors, with claims of forgery attributed to artists born a century apart. Some contend that the Lirey shroud was the work of a confessed forger and murderer.[24] Professor Larissa Tracy, of Virginia also argues that the shroud in Turin is a forgery, but that it was forged by Leonardo da Vinci, who was born in 1452. Professor Nicholas Allen of South Africa on the other hand believes that the image was made photographically and not by an artist. Professor John Jackson of Colorado argues that the shroud in Turin dates back to the first century AD.[25][26][27][28][29]

The history of the shroud from the middle of 16th century is well recorded. The existence of a miniature by Giulio Clovio, which gives a good representation of what was seen upon the shroud about the year 1540, confirms that the shroud housed in Turin today is the same one as in the middle of the 16th century.[17]

In 1532, the shroud suffered damage from a fire in the chapel where it was stored. A drop of molten silver from the reliquary produced a symmetrically placed mark through the layers of the folded cloth. Poor Clare Nuns attempted to repair this damage with patches. In 1578 the House of Savoy took the shroud to Turin and it has remained at Turin Cathedral ever since.[31]

Repairs were made to the shroud in 1694 by Sebastian Valfrè to improve the repairs of the Poor Clare nuns.[32] Further repairs were made in 1868 by Clotilde of Savoy.[33] The shroud remained the property of the House of Savoy until 1983, when it was given to the Holy See, the rule of the House of Savoy having ended in 1946.

A fire, possibly caused by arson, threatened the shroud on 11 April 1997, but a fireman saved it from significant damage.[34] In 2002, the Holy See had the shroud restored. The cloth backing and thirty patches were removed, making it possible to photograph and scan the reverse side of the cloth, which had been hidden from view. A ghostly part-image of the body was found on the back of the shroud in 2004.[35] The most recent public exhibition of the Shroud was in 2000 for the Great Jubilee. The next scheduled exhibition is in 2010.[36]

Religious perspective

Religious beliefs about the burial cloths of Jesus have existed for centuries. The Gospels of Matthew27:59–60, Mark15:46 and Luke23:53 state that Joseph of Arimathea wrapped the body of Jesus in a piece of linen cloth and placed it in a new tomb. The Gospel of John20:6–7 states that Apostle Peter found multiple pieces of burial cloth after the tomb was found open, strips of linen cloth for the body and a separate cloth for the head.

Although pieces of burial cloths of Jesus are claimed by at least four churches in France and three in Italy none has gathered as much religious following as the Shroud of Turin.[37] The religious beliefs and practices associated with the shroud predate historical and scientific discussions and have continued in the 21st century, although the Catholic Church has never claimed its authenticity.[38] An example is the Holy Face Medal bearing the image from the shroud, worn by some Catholics.[39]

Devotions

Although the shroud image is currently associated with Catholic devotions to the Holy Face of Jesus, the devotions themselves predate Secondo Pia's 1898 photograph. Such devotions had been started in 1844 by the Carmelite nun Marie of St Peter (based on "pre-crucifixion" images associated with the Veil of Veronica) and promoted by Leo Dupont, also called the Apostle of the Holy Face. In 1851 Leo Dupont formed the "Archconfraternity of the Holy Face" in Tours, France, well before Secondo Pia took the photograph of the shroud.[40]

Miraculous image

The religious concept of "miraculous image" has been applied to the Shroud of Turin, as it has been applied to other religious artifacts such as the image of the Virgin Mary on the cloak in the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe on Tepeyac hill in Mexico.[41][42]

Without debating scientific issues, some believers state as a matter of faith that empirical analysis and scientific methods will perhaps never advance to a level sufficient for understanding the divine methods used for image formation on the shroud, since the body around whom the shroud was wrapped was not merely human, but divine, and believe that the image on the shroud was miraculously produced at the moment of Resurrection.[43][44] Quoting Pope Paul VI's statement that the shroud is "the wonderful document of His Passion, Death and Resurrection, written for us in letters of blood" author Antonio Cassanelli argues that the shroud is a deliberate divine record of the five stages of the Passion of Christ.[45]

Vatican position

The Vatican newspaper Osservatore Romano covered the story of Secondo Pia's photograph of May 28, 1898 in its June 15, 1898 edition, but it did so with no comment and thereafter Church officials generally refrained from officially commenting on the photograph for almost half a century.

The first official association between the image on the Shroud and the Catholic Church was made in 1940 based on the formal request by Sister Maria Pierina De Micheli to the curia in Milan to obtain authorization to produce a medal with the image. The authorization was granted and the first medal with the image was offered to Pope Pius XII who approved the medal. The image was then used on what became known as the Holy Face Medal worn by many Catholics, initially as a means of protection during the Second World War. In 1958 Pope Pius XII approved of the image in association with the devotion to the Holy Face of Jesus, and declared its feast to be celebrated every year the day before Ash Wednesday.[46][47] Following the approval by Pope Pius XII, Catholic devotions to the Holy Face of Jesus have been almost exclusively associated with the image on the shroud.

In 1983 the Shroud was given to the Holy See by the House of Savoy.[48] However, as with all relics of this kind, the Roman Catholic Church made no pronouncements claiming whether it is Jesus' burial shroud, or if it is a forgery. As with other approved Catholic devotions, the matter has been left to the personal decision of the faithful, as long as the Church does not issue a future notification to the contrary. In the Church's view, whether the cloth is authentic or not has no bearing whatsoever on the validity of what Jesus taught nor on the saving power of his death and resurrection.[49][50]

Pope John Paul II stated in 1998 that:[51]: "Since we're not dealing with a matter of faith, the church can't pronounce itself on such questions. It entrusts to scientists the tasks of continuing to investigate, to reach adequate answers to the questions connected to this Shroud." Pope John Paul II showed himself to be deeply moved by the image of the Shroud and arranged for public showings in 1998 and 2000. In his address at the Turin Cathedral on Sunday May 24, 1998 (the occasion of the 100th year of Secondo Pia's May 28, 1898 photograph), he said:[52] "The Shroud is an image of God's love as well as of human sin ... The imprint left by the tortured body of the Crucified One, which attests to the tremendous human capacity for causing pain and death to one's fellow man, stands as an icon of the suffering of the innocent in every age." In 2000, Cardinal Ratzinger wrote that the Shroud of Turin is ″a truly mysterious image, which no human artistry was capable of producing. In some inexplicable way, it appeared imprinted upon cloth and claimed to show the true face of Christ, the crucified and risen Lord."[53]

Pope Benedict XVI has not publicly commented on the Shroud's authenticity, but has taken steps that indirectly affect the Shroud. In June 2008 he approved the public display of the Shroud in the Spring of 2010 and stated that he would like to go to Turin to see it along with other pilgrims.[54] In April 2009 Pope Benedict XVI advanced the beatification process of Sister Maria Pierina De Micheli who coined the Holy Face Medal, based on Secondo Pia's photograph of the Shroud, by formally recognizing a miracle attributed to her.[55][56]

Scientific analysis

This section may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (March 2010) |

The term sindonology (from the Greek σινδών—sindon, the word used in the Gospel of Mark15:46 to describe the type of the burial cloth of Jesus) is used to refer to the formal study of the Shroud.

A variety of scientific theories regarding the shroud have since been proposed, based on disciplines ranging from chemistry to biology and medical forensics to optical image analysis. The scientific approaches to the study of the Shroud fall into three groups: material analysis (both chemical and historical), biology and medical forensics and image analysis.

Early studies

The first scientific examinations of the Turin Shroud began in 1900. The pathophysiological studies under the direction of Yves Delage, professor of comparative anatomy, revealed the anatomical flawlessness of the image.[57] The features of rigor mortis, wounds, and blood flows provided an evidence that the image was formed by direct or indirect contact with a corpse and was neither painted on the cloth nor scorched by a hot pattern.[57] On this issue all medical opinions since Delage has been unanimous (notably Hynek 1936, Vignon 1939, Moedder 1949, Caselli 1950, La Cava 1953, Sava 1957, Judica-Cordiglia 1961, Barbet 1963, Bucklin 1970 or Cameron 1978).[57] Two theories, each supported by tests or wartime observations, have been put forward about the cause of death: asphyxiation due to muscular spasm, progressive rigidity and inability to exhale (Barbet, Hynek, Bucklin) or circulatory failure from lowering of blood pressure and pooling of blood in the lower extremities (Moedder, Willis).[57]

Material chemical analysis

Image formation

The Maillard reaction is a form of non-enzymatic browning involving an amino acid and a reducing sugar. The cellulose fibers of the shroud are coated with a thin carbohydrate layer of starch fractions, various sugars, and other impurities. In a paper entitled "The Shroud of Turin: an amino-carbonyl reaction may explain the image formation,"[58] R.N. Rogers and A. Arnoldi propose that amines from a recently deceased human body may have undergone Maillard reactions with this carbohydrate layer within a reasonable period of time, before liquid decomposition products stained or damaged the cloth. The gases produced by a dead body are extremely reactive chemically and within a few hours, in an environment such as a tomb, a body starts to produce heavier amines in its tissues such as putrescine and cadaverine.

Alan A. Mills argued that the image was formed by the chemical reaction auto-oxidation. He noted that the image corresponds to what would have been produced by a volatile chemical if the intensity of the color change were inversely proportional to the distance from the body of a loosely draped cloth.[59]

Radiocarbon dating

After years of discussion, the Holy See finally permitted radiocarbon dating on portions of a swatch taken from a corner of the shroud. Independent tests in 1988 at the University of Oxford, the University of Arizona, and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology concluded that the shroud material dated to 1260-1390 AD, with 95% confidence.[60] This 13th to 14th century dating matches the first appearance of the shroud in church history,[17] and is somewhat later than art historian W.S.A. Dale's estimate of an 11th century date based on art-historical grounds.[61]

Chemical properties of the sample site

One argument against the results of the radiocarbon tests was made in a study by Anna Arnoldi of the University of Milan and Raymond Rogers, retired Fellow of the University of California Los Alamos National Laboratory. In an interview with Harry Gove, Gove acknowledges that bacterial contamination, which was unknown during the 1988 testing, would render the tests inaccurate, although he also acknowledged that the samples had been carefully cleaned with strong chemicals before testing.[62] By ultraviolet photography and spectral analysis they determined that the area of the shroud chosen for the test samples differs chemically from the rest of the cloth. They cite the presence of Madder-root dye and aluminum-oxide mordant (a dye-fixing agent) specifically in that corner of the shroud and conclude that this part of the cloth may have been mended at some point in its history.

In 1994, J. A. Christen applied a strong statistical test to the radiocarbon data and concludes that the given age for the shroud is, from a statistical point of view, correct.[63]. To the contrary Raymond Rogers' 20 January 2005 paper[64] in the scientific journal Thermochimica Acta argues that the sample cut from the shroud in 1988 was not representative. Rogers concludes, based upon the vanillin loss, that the shroud is between 1,300 and 3,000 years old. Rogers said: "The fact that vanillin cannot be detected in the lignin on shroud fibers, Dead Sea scrolls linen, and other very old linens indicate that the shroud is quite old. A determination of the kinetics of vanillin loss suggest the shroud is between 1300- and 3000-years old. Even allowing for errors in the measurements and assumptions about storage conditions, the cloth is unlikely to be as young as 840 years"[65]

In 2006, Brendan Whiting, an Australian author and researcher who attended several of Dr. Raymond Rogers key conferences, published the book The Shroud Story (ISBN 064645725X) continued this new challenge to the validity of the 1988 sample.[66]

Skeptics contend that the carbon dating was accurate and that Rogers' study was flawed.[67]

The shroud was also damaged by a fire in the Late Middle Ages which could have added carbon material to the cloth, resulting in a higher radiocarbon content and a later calculated age. This analysis itself is questioned by skeptics such as Joe Nickell, who reasons that the conclusions of the author, Raymond Rogers, result from "starting with the desired conclusion and working backward to the evidence".[68] Former Nature editor Philip Ball has said that the idea that Rogers steered his study to a preconceived conclusion is "unfair" and Rogers "has a history of respectable work".

However, the 2008 research at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit may revise the 1260–1390 dating toward which it originally contributed, leading its director Christopher Ramsey to call the scientific community to probe anew the authenticity of the Shroud.[5][6][7] "With the radiocarbon measurements and with all of the other evidence which we have about the Shroud, there does seem to be a conflict in the interpretation of the different evidence" Ramsey said to BBC News in 2008, after the new research emerged.[7] Ramsey had stressed that he would be surprised if the 1988 tests were shown to be far off, let alone "a thousand years wrong" but said that he would keep an open mind.

In 2008, an article by Sue Benford and Joseph Marino, based on x-ray analysis of the sample sites and textile analysis, find discrepancies in the radiocarbon dating area. The authors conclude that "the radiocarbon sampling area was manipulated during or after the 16th century"[69].

Recently in a new documentary a video message from Ray Rogers, who was a director of the Shroud of Turin Research Project, has come to light. The video was recorded shortly before Rogers' death in 2005, and in it Rogers states the opinion that after declaring the cloth a fake he was now coming to the conclusion that there was a very good chance that this was the piece of cloth that was used to bury Jesus.[70]

Bacterial residue

A team led by Leoncio A. Garza-Valdes, MD, adjunct professor of microbiology, and Stephen J. Mattingly, PhD, professor of microbiology at the University of Texas at San Antonio have expounded an argument involving bacterial residue on the shroud.[71] There are examples of ancient textiles that have been grossly misdated, especially in the earliest days of radiocarbon testing. Most notable of these is mummy 1770 of the British Museum, whose bones were dated some 800 to 1000 years earlier than its cloth wrappings. The skewed results were thought to be caused by organic contaminants on the wrappings similar to those proposed for the shroud. Pictorial evidence dating from c. 1690 and 1842[72] indicates that the corner used for the dating and several similar evenly spaced areas along one edge of the cloth were handled each time the cloth was displayed, the traditional method being for it to be held suspended by a row of five bishops. Wilson and others contend that repeated handling of this kind greatly increased the likelihood of contamination by bacteria and bacterial residue compared to the newly discovered archaeological specimens for which carbon-14 dating was developed. Bacteria and associated residue (bacteria by-products and dead bacteria) carry additional carbon-14 that would skew the radiocarbon date toward the present.

Harry E. Gove of the University of Rochester, the nuclear physicist who designed the particular radiocarbon tests used on the shroud in 1988, stated, "There is a bioplastic coating on some threads, maybe most." If this coating is thick enough, according to Gove, it "would make the fabric sample seem younger than it should be." Skeptics, including Rodger Sparks, a radiocarbon expert from New Zealand, have countered that an error of thirteen centuries stemming from bacterial contamination in the Middle Ages would have required a layer approximately doubling the sample weight.[73] Because such material could be easily detected, fibers from the shroud were examined at the National Science Foundation Mass Spectrometry Center of Excellence at the University of Nebraska. Pyrolysis-mass-spectrometry examination failed to detect any form of bioplastic polymer on fibers from either non-image or image areas of the shroud. Additionally, laser-microprobe Raman analysis at Instruments SA, Inc. in Metuchen, New Jersey, also failed to detect any bioplastic polymer on shroud fibers.

Detailed discussion of carbon-dating

There are two books with detailed treatment of the Shroud's carbon dating, including not only the scientific issues but also the events, personalities and struggles leading up to the sample taking. The books offer opposite views on how the dating should have been conducted, and both are critical of the methodology finally employed.

In Relic, Icon or Hoax? Carbon Dating the Turin Shroud (1996; ISBN 0750303980), Harry Gove provides an account with large doses of light humor and heavy vitriol. Particular scorn is poured on STURP (the US scientific team studying the Shroud) and Luigi Gonella, then scientific adviser to the Archbishop of Turin, Cardinal Ballestrero. Gove describes in great detail the mammoth struggle between Prof Carlos Chagas, chairman of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, and Cardinal Ballestrero, with Gove and Gonella as the main combatants from each side. He provides a detailed record of meetings, telephone conversations, faxes, letters and maneuvers. Gove initially accepted the dating as accurate, but in the epilogue notes that the bioplastic contamination theory seemed to have some evidence to support it.

The Rape of the Turin Shroud by William Meacham (2005; ISBN 1411657691) devotes 100 pages to the carbon dating. Meacham is also highly critical of STURP and Gonella, and also of Gove. He describes the planning process from a very different perspective (both he and Gove were invited along with 20 other scholars to a conference in Turin in 1986 to plan the C-14 protocol) and focuses on what he claims was the major flaw in the dating: taking only one sample from the corner of the cloth. Meacham reviews the main scenarios that have been proposed for a possibly incorrect dating, and claims that the result is a "rogue date" because of the sample location and anomalies. He points out that this situation could easily be resolved if the Church authorities would simply allow another sample to be dated, with appropriate laboratory testing for possible embedded contaminants.

Painting and pigments

The technique used for producing the image is, according to W. McCrone, already described in a book about medieval painting published in 1847 by Charles Lock Eastlake ("Methods and Materials of Painting of the Great Schools and Masters"). Eastlake describes in the chapter "Practice of Painting Generally During the XIVth Century" a special technique of painting on linen using tempera paint, which produces images with unusual transparent features—which McCrone compares to the image on the shroud.[74]

In 1970s a special eleven-member Turin Commission conducted several tests. Conventional and electron microscopic examination of the Shroud at that time revealed an absence of heterogeneous coloring material or pigment.[57]

In 1977, a team of scientists proposed a set of tests to be conducted on the Shroud, designated the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP). Cardinal Anastasio Ballestrero, the archbishop of Turin, granted permission, despite disagreement within the Church. STURP scientists conducted the tests over five days in 1978. Walter McCrone, upon analyzing the samples he was given by STURP, concluded in 1979 that the image is actually made up of billions of submicrometre pigment particles.[75] The only fibrils that had been made available for testing of the stains were those that remained affixed to custom-designed adhesive tape applied to thirty-two different sections of the image. (This was done in order to avoid damaging the cloth.) According to McCrone, the pigments used were a combination of red ochre and vermillion tempera paint. The Electron Optics Group of McCrone Associates published the results of these studies in five articles in peer-reviewed journals: Microscope 1980, 28, 105, 115; 1981, 29, 19; Wiener Berichte uber Naturwissenschaft in der Kunst 1987/1988, 4/5, 50 and Acc. Chem. Res. 1990, 23, 77–83.

Dr. John Heller and Dr. Alan Adler, the scientists whom STURP asked for a second opinion after McCrone's, examined the same samples. They confirmed McCrone's result that the cloth contains iron oxide. However, they concluded, the exceptional purity of the chemical and comparisons with other ancient textiles showed that, while retting flax absorbs iron selectively, the iron itself was not the source of the image on the shroud.[76] McCrone has responded saying "My colleagues at McCrone Associates used X-ray fluorescence and X-ray and electron diffraction on the samples, which confirmed my research in every respect"[77]

Other microscopic analysis of the fibers seems to indicate that the image is strictly limited to the carbohydrate layer, with no additional layer of pigment visible. Proponents of the position that the Shroud is authentic say that no known technique for hand application of paint could apply a pigment with the necessary degree of control on such a nano-scale fibrillar surface plane. Moreover, they claim the technical skill required to produce the photographic or near-photographic realism in the image on the Shroud would be unrealistically advanced for the twelfth or thirteenth century.[78]

Material historical analysis

Historical fabrics

In 2000, fragments of a burial shroud from the first century were discovered in a tomb near Jerusalem, believed to have belonged to a Jewish high priest or member of the aristocracy. The shroud was composed of a simple two-way weave, unlike the complex weave of the Turin Shroud. Based on this discovery, researchers concluded that the Turin Shroud did not originate from Jesus-era Jerusalem.[79][80][81]

According to textile expert Mechthild Flury-Lemberg of Hamburg, a seam in the cloth corresponds to a fabric found only at the fortress of Masada near the Dead Sea, which dated to the first century. The weaving pattern, 3:1 twill, is consistent with first-century Syrian design, according to the appraisal of Gilbert Raes of the Ghent Institute of Textile Technology in Belgium. Flury-Lemberg stated, "The linen cloth of the Shroud of Turin does not display any weaving or sewing techniques which would speak against its origin as a high-quality product of the textile workers of the first century."[82]

In 1999 Mark Guscin investigated the relationship between the shroud and the Sudarium of Oviedo, claimed as the cloth that covered the head of Jesus as in John 20:7 when the empty tomb was discovered. The Sudarium is also reported to have type AB blood stains. Guscin concluded that the two cloths covered the same head at two distinct, but close moments of time. Avinoam Danin (see above) concurred with this analysis, adding that the pollen grains in the Sudarium match those of the shroud.[83] Skeptics criticize the polarized image overlay technique of Guscin and suggest that pollen from Jerusalem could have followed any number of paths to find its way to the sudarium.[84]

In 2002, Aldo Guerreschi and Michele Salcito argued that that many of these marks on the fabric of the shroud stem from a much earlier time because the symmetries correspond more to the folding that would have been necessary to store the cloth in a clay jar (like cloth samples at Qumran) than to that necessary to store it in the reliquary that housed it in 1532.[85]

Dirt particles

Joseph Kohlbeck from the Hercules Aerospace Center in Utah and Richard Levi-Setti of the Enrico Fermi Institute examined some dirt particles from the Shroud surface. The dirt was found to be travertine aragonite limestone.[86] Using a high-resolution microprobe, Levi-Setti and Kolbeck compared the spectra of samples taken from the Shroud with samples of limestone from ancient Jerusulem tombs. The chemical signatures of the Shroud samples and the tomb limestone were found identical except for minute fragments of cellulose linen fiber that could not be separated from the Shroud samples.[87]

Biological and medical forensics

Blood stains

There are several reddish stains on the shroud suggesting blood. McCrone (see above) identified these as containing iron oxide, theorizing that its presence was likely due to simple pigment materials used in medieval times. This is in agreement with the results of an Italian commission investigating the shroud in the early 1970s. Serologists among the commission applied several different state-of-the-art blood tests which all gave a negative result for the presence of blood. No test for the presence of color pigments was performed by this commission.[88] Other researchers, including Alan Adler, a chemist specializing in analysis of porphyrins, identified the reddish stains as type AB blood and interpreted the iron oxide as a natural residue of hemoglobin.

A problem with a blood type AB for an authentic shroud is that it is today known that this type of blood is of relative recent origin. There is no evidence of the existence of this blood type before the year AD 700. It is today assumed that the blood type AB came into the existence by immigration and following intermingling of mongoloid people from central Asia with a high frequency of the blood type B to Europe and other areas where people with a relatively high frequency of the blood type A live.[89][90]

Drs. Heller and Adler further studied the dark red stains. Applying pleochroism, birefringence, and chemical analysis, they determined that, unlike the medieval artist's pigment which contains iron oxide contaminated with manganese, nickel, and cobalt, the iron oxide on the shroud was relatively pure but later proven to be iron oxide resulting from blood stains (Heller, J.H., Adler, A.D. 1980). Dr. Adler then applied microspectrophotometric analysis of a "blood particle" from one of the fibrils of the shroud and identified hemoglobin (in the acid methemoglobin, which formed due to great age and denaturation). Further tests by Heller and Adler established, within claimed scientific certainty, the presence of porphyrin, bilirubin, albumin, and protein. Interestingly, when proteases (enzymes which break up protein within cells) were applied to the fibril containing the "blood", the blood dissolved from the fibril leaving an imageless fibril (Heller, J.H., and Adler, A.D. 1981). Template:PDFlink. It is uncertain whether the blood stains were produced at the same time as the image, which Adler and Heller attributed to premature aging of the linen.[91] Working independently with a larger sample of blood-containing fibrils, pathologist Pier Baima Bollone, after using immunochemistry, concurred with Heller and Adler's findings and identifies the blood as being from the AB blood group (Baima Bollone, P., La Sindone-Scienza e Fide 1981). Subsequently, STURP sent blood flecks to the laboratory devoted to the study of ancient blood at the State University of New York. No claims about blood typing could be confirmed. The blood appeared to be so old that the DNA was badly fragmented. Dr. Andrew Merriwether at SUNY said that "... anyone can walk in off the street and amplify DNA from anything. The hard part is not to amplify what you don't want and only amplify what you want (endogenous DNA vs contamination)."[92]

Joe Nickell notes that, unlike McCrone, Heller and Adler are neither forensic serologists nor pigment experts, nor are they experienced in detecting art forgeries. Nickell makes reference to the 1983 conference of the International Association for Identification where forensic analyst John E. Fischer demonstrated how results similar to Heller and Adler's could be obtained from tempera paint.[93] Skeptics also cite other forensic blood tests whose results dispute the authenticity of the Shroud. "Forensic tests on the red stuff have identified it as red ocher and vermilion tempera paint."[84] Even if blood is found, "it could be the blood of some 14th century person. It could be the blood of someone wrapped in the shroud, or the blood of the creator of the shroud, or of anyone who has ever handled the shroud, or of anyone who handled the sticky tape. But even if there were blood on the shroud, that would have no bearing on the age of the shroud or on its authenticity."[84] Skeptics also note that the apparent blood flows on the shroud are unrealistically neat. Leading forensic pathologist Michael Baden observes that real blood never oozes in neat rivulets, it gets clotted in the hair. He concludes that "[h]uman beings don't produce this kind of pattern."[94] The same result was established by McCrone which had compared the shroud pigments with test specimen of his own blood on gauze.[95]

Pollen grains

Researchers of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem reported the presence of pollen grains in the cloth samples, showing species appropriate to the spring in Israel. However, these researchers, Avinoam Danin and Uri Baruch, were working with samples provided by Max Frei, a Swiss police criminologist who had previously been censured for faking evidence. Independent review of the strands showed that one strand out of the 26 provided contained significantly more pollen than the others, perhaps pointing to deliberate contamination.[96]. (Note: there is NO proof that Max Fei faked any evidence in this particular situation).

The Israeli researchers also detected the outlines of various flowering plants on the cloth, which they say would point to March or April and the environs of Jerusalem, based on the species identified. In the forehead area, corresponding to the crown of thorns if the image is genuine, they found traces of Gundelia tournefortii, which is limited to this period of the year in the Jerusalem area. This analysis depends on interpretation of various patterns on the shroud as representing particular plants. Skeptics point out that the available images cannot be seen as unequivocal support for any particular plant species due to the generally indistinct "blobiness", even under powerful microscopes, of these tiny, spotty impressions.

According to the author of The Resurrection of the Shroud, 45 of the 58 pollens found on the Shroud grow in Jerusalem. Additionally, pollen were found from six plants grown in Anatolia (Turkey) and the eastern Mediteranian. This physical evidence clearly establishes a linking of the Shroud to Jerusalem (78% of all pollen types) and to the middle east, including Edessa (circa AD 500) because of the pollen from Anatolia (page 111).

Image analysis

Digital image processing

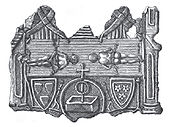

NASA researchers Jackson, Jumper, and Stephenson report detecting the impressions of coins placed on both eyes after a digital study in 1978.[97] The coin on the right eye was claimed to correspond to a Roman copper coin produced in AD 29 and 30 in Jerusalem, while that on the left was claimed to resemble a lituus (lepton) coin from the reign of Tiberius.[98] Greek and Latin letters were discovered written near the face (Piero Ugolotti, 1979). These were further studied by André Marion, professor at the École supérieure d'optique and his student Anne Laure Courage, graduate engineer of the École supérieure d'optique, in the Institut d'optique théorique et appliquée in Orsay (1997).

Image analysis by scientists at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory found that rather than being like a photographic negative, the image unexpectedly has the property of decoding into a 3-D image of the man when the darker parts of the image are interpreted to be those features of the man that were closest to the shroud and the lighter areas of the image those features that were farthest. This is not a property that occurs in photography, and researchers could not replicate the effect when they attempted to transfer similar images using techniques of block print, engravings, a hot statue, and bas-relief.[99]

During restoration in 2002, the back of the cloth was photographed and scanned for the first time. An Template:PDFlink on this subject by Giulio Fanti of the University of Padua and others, describe the electrostatic corona discharge as the probable mechanism to produce the images of the body in the shroud. Congruent with that mechanism, they also describe an image on the reverse side of the fabric, much fainter than that on the front view of the body, consisting primarily of the face and perhaps hands. Like the front picture, it is entirely superficial, with coloration limited to the carbohydrate layer. The images correspond to, and are in registration with, those on the other side of the cloth. No image is detectable in the reverse side of the dorsal view of the body.

Supporters of the Maillard reaction theory point out that the gases would have been less likely to penetrate the entire cloth on the dorsal side, since the body would have been laid on a stone shelf. At the same time, the second image makes the electrostatic hypothesis[100]

Photographic image production

According to the art historian Nicolas Allen the image on the shroud was formed by a photographic technique in the 13th century.[101] Allen maintains that techniques already available before the 14th century, as e.g. described in the Book of Optics which was just in this time translated from Arabic into Latin, were sufficient to produce primitive photographs and that people familiar with these techniques could be able to produce an image as found on the shroud. To demonstrate this, he has successfully produced photographic images similar to the shroud using only techniques and materials available at the time the shroud was made. He described his results in his PhD Thesis,[102] in papers published in several science journals,[103][104] and in a book.[105]

Dust-transfer technique

Scientists Emily Craig and Randall Bresee have attempted to recreate the likenesses of the shroud through the dust-transfer technique which could have been done by medieval arts. They first did a carbon-dust drawing of a Jesus-like face (using collagen dust) on a newsprint made from wood pulp (which is similar, but not identical to, 13th and 14th century paper). They next placed the drawing on a table and covered it with a piece of linen. They then pressed the linen against the newsprint by firmly rubbing with the flat side of a wooden spoon. By doing this they managed to create a reddish brown image with a life-like positive likeness of a person, a three dimensional image and no sign of brush strokes.[106]

Recent developments

On April 6, 2009, the London newspaper The Times reported that official Vatican researchers had uncovered evidence that the Shroud had been kept and venerated by the Templars since the 1204 sack of Constantinople. According to the account of one neophyte member of the order, veneration of the Shroud appeared to be part of the initiation ritual. The article also implies that this ceremony may be the source of the 'worship of a bearded figure' that the Templars were accused of at their 14th century trial and suppression.[107]

On April 10, 2009, the Telegraph reported that original Shroud investigator, Ray Rogers, acknowledged the radio carbon dating performed in 1988 was flawed.[108] The sample used for dating may have been taken from a section damaged by fire and repaired in the 16th century, which would not provide an estimate for the original material. Shortly before his death, Rogers said:

"The worst possible sample for carbon dating was taken."[108] "It consisted of different materials than were used in the shroud itself, so the age we produced was inaccurate."[108] "...I am coming to the conclusion that it has a very good chance of being the piece of cloth that was used to bury the historic Jesus."[108]

A recent study by French scientist Thierry Castex has revealed that on the shroud are traces of words in Aramaic spelled with Hebrew letters. Barbara Frale, a Church scholar, told Vatican Radio on July 26, 2009 that her own studies suggest the letters on the shroud were written more than 1,800 years ago.[109]

On October 5, 2009 Luigi Garlaschelli, professor of organic chemistry at the University of Pavia, announced that he had made a full size reproduction of the Shroud of Turin using only medieval technologies. Garlaschelli placed a linen sheet over a volunteer and then rubbed it with an acidic pigment. The shroud was then aged in an oven before being washed to remove the pigment. He then added blood stains, scorches and water stains to replicate the original. The image on the reproduction closely matched that of the Turin shroud with differences explained as the result of natural fading over the centuries.[110]

In a rebuttal to the creation by Luigi Garlaschelli, shroud scholar Petrus Soons explains why the Italian Fake does not reproduce the Shroud of Turin.[111] The image on the Garlaschelli cloth was created using a red ochre based paint. In 1978 the original STURP team ruled this out as a possibility for the following reasons: [citation needed] 1) Adler reported that the " straw yellow color" of the body image fibers does not match the color of any of the known forms of ferric iron oxides. 2) Moreover, Adler reports that there is no correspondence of the body-only images to the concentration of iron oxide since the spectral characteristics of the body-only image are different from those of iron oxide. 3) The colors of the fibers, due to iron oxide, is also precluded by the fact that oxidation or reduction converts the yellow fibers of the body-only image to a white color. 4) Only rare particles of iron oxide are noted on the body-only image fibrils. 5) Large amounts of iron bound to the cellulose of the Shroud (not iron oxide) and Calcium were both present throughout the Shroud. This is believed to be due to the ability of linen to bind iron and water by ion association during the retting process (manufacturing process by which linen is immersed in water during fermentation). An estimated 90% of the iron and calcium exist in this form bound to the cellulose of the linen, and only a small amount is present as iron oxide. 6) X-ray studies of the body-only image do not contain enough iron oxide to show up on the X-radiographs. 7) All of the iron of the Shroud, whether from iron oxide particles or from blood, proved to be 99 percent chemically pure, with no discernable manganese, nickel, or cobalt. Prof Garlaschelli explains the absence of any traces of iron oxide on the original Shroud by stating that the pigment on the original Shroud faded away naturally over the centuries.

In November 2009 Dr. Barbara Frale, a Roman Catholic researcher at the Vatican secret archives, announced that she had "managed to read the burial certificate of Jesus the Nazarene, or Jesus of Nazareth." imprinted in fragments of Greek, Hebrew and Latin writing, together with the image of a crucified man on the cloth. She asserted that the inscription provided an "historical date consistent with the Gospels account" and that the letters, not obvious to the human eyes, were first detected during an examination of the shroud in 1978, with others since coming to light. Like the image of the man himself Frale reports that the letters are in reverse and only become intelligible in negative photographs. Frale further asserts that under contemporary Jewish burial practices, within a Roman colony such as Palestine, a body buried after a death sentence could only be returned to the family after a year in a common grave (though the gospels report that Jesus was buried in a tomb provided by Joseph of Arimathea), therefore a death certificate was glued to the burial shroud, usually stuck to the face, to identify it for later retrieval.

Other scholars have argued that the writing originates from a reliquary that the cloth was housed in during medieval times. Frale disagrees on her assumption that a medieval Christian would not have referred to Jesus as "the Nazarene" but rather "Jesus as Christ" since the former would have been "heretical" in the Middle Ages, defining Jesus as being "only a man" rather than the Son of God. Frale's reconstruction of the text reads:

- "In the year 16 of the reign of the Emperor Tiberius Jesus the Nazarene, taken down in the early evening after having been condemned to death by a Roman judge because he was found guilty by a Hebrew authority, is hereby sent for burial with the obligation of being consigned to his family only after one full year".

Frale further argues that the use of three languages was in line with the multi-lingual practices of Greek-speaking Jews in a Roman colony.[112]

In December, 2009, archaeologists unearthed a burial shroud from the time of Jesus in the Field of Blood cemetery in Jerusalem. Believed to be belonging to a Jewish high priest or member of the aristocracy who died from leprosy, the newly found cloth has a much simpler two-way weave than the Shroud of Turin's complex herringbone weave. The researchers believe that the cloth is representative of the typical burial cloths used at the time and conclude that the Turin Shroud did not originate from 1st Century Jerusalem.[113]

In 2010, John Lupia argued that image formation can be explained by risidual unguent from anointing the body at burial.[114]

In 2010, three professors of statistics wrote in a scientific paper that the statistical analysis of the raw dates obtained from the three laboratories suggests "the presence of an important contamination in the 1988 TS samples"[115].

See also

References

- ^ Bernard Ruffin, 1999, The Shroud of Turin ISBN 0879736178

- ^ Summary of STURP's Conclusions (1981)

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Turin_Naturewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Ashall, Frank. Remarkable Discoveries!. Cambridge University Press. p. 36. ISBN 0521589533.

- ^ a b Daily Telegraph article on Carbon dating http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2008/02/25/nshroud125.xml

- ^ a b Lorenzi, Rossella. "Shroud of Turin's Authenticity Probed Anew". Discovery Channel. Discovery Communications. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- ^ a b c Shroud mystery refuses to go away: BBC News 2008 http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/7307646.stm

- ^ The orphaned manuscript: a gathering of publications on the Shroud of Turin by Alan D. Adler 2002 ISBN 8874020031 page 103

- ^ Heller, John H. Report on the Shroud of Turin. Houghton Mifflin, 1983. ISBN 0395339677

- ^ Bernard Ruffin, 1999, The Shroud of Turin ISBN 0879736178 page 14

- ^ Bernard Ruffin, 1999, The Shroud of Turin ISBN 0879736178 page 14

- ^ Architecture for the shroud: relic and ritual in Turin by John Beldon Scott 2003 ISBN 0226743160 page 302

- ^ "How Tall is the Man of the Shroud of Turin". Shroudofturin4journalists.com. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- ^ Joan Carroll Cruz, 1984 Relics ISBN 0879737018 page 49

- ^ William Meacham, The Authentication of the Turin Shroud:An Issue in Archaeological Epistemology, Current Anthropology, Volume 24, No 3, June 1983. [1]

- ^ Hidden History by Brian Haughton 2007 ISBN 1564148971 page 117

- ^ a b c Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Holy Shroud of Turin by Arthur Stapylton Barnes 2003 ISBN 0766134253 page 49

- ^ The Mysterious Shroud of Turin by Guido Pagliarino 2007 ISBN 1847538215 page 15

- ^ The Turin Shroud: How Da Vinci Fooled History by Lynn Picknett, Clive Prince 2007 ISBN 0743292170

- ^ Architecture for the shroud: relic and ritual in Turin by John Beldon Scott 2003 ISBN 0226743160 page xxi

- ^ Hidden History by Brian Haughton 2007 ISBN 1564148971 page 118

- ^ Humber, Thomas: The Sacred Shroud. New York: Pocket Books, 1980. ISBN 0-671-41889-0

- ^ Mercer dictionary of the Bible by Watson E. Mills, Roger Aubrey Bullard 1998 ISBN 0865543739 page 822

- ^ "Was Turin Shroud faked by Leonardo da Vinci?". telegraph. Retrieved 2009-07-03.

- ^ The Independent, Ireland, July 1, 2009, Turin Shroud may have been faked by da Vinci [2]

- ^ Seattle Times, August 24, 2008, Turin shroud controversy envelops pair[3]

- ^ BBC News March 21, 2008 Shroud mystery refuses to go away [4]

- ^ The Turin Shroud: How Da Vinci Fooled History by Lynn Picknett, Clive Prince 2007 ISBN 0743292170

- ^ The Shroud of Christ by Paul Vignon, Paul Tice 2002 ISBN 1885395965 page 21

- ^ The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia:Q-Z by Geoffrey W. Bromiley 1995 ISBN 0802837840 page 495

- ^ Architecture for the shroud: relic and ritual in Turin by John Beldon Scott 2003 ISBN 0226743160 page 26

- ^ Holy Shroud of Turin by Arthur Stapylton Barnes 2003 ISBN 0766134253 page 62

- ^ NY Times April 12, 1997 Shroud of Turin Saved From Fire in Cathedral [5]

- ^ Hidden History by Brian Haughton 2007 ISBN 1564148971 page 120

- ^ NY Times Jan 10, 2010 [6]

- ^ Joan Carrol Cruz, 1984 Relics ISBN 0879737018 page 55

- ^ Ann Ball, 2003 Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices ISBN 087973910X page 533

- ^ Ann Ball, 2003 Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices ISBN 087973910X page 239

- ^ Dorothy Scallan. "The Holy Man of Tours." (1990) ISBN 0895553902

- ^ Joan Carrol Cruz, 1984 Relics ISBN 0879737018 page 77

- ^ Michael Freze, 1993, Voices, Visions, and Apparitions, OSV Publishing ISBN 087973454X page 57

- ^ Charles S. Brown, 2007 Bible "Mysteries" Explained ISBN 0958281300 page 193

- ^ Peter Rinaldi 1972, The man in the Shroud ISBN 0860070107 page 45

- ^ Antonio Cassanelli, 2001 The Holy Shroud: a comparison between the Gospel narrative of the five stages of the Passion ISBN 085244351X page 13

- ^ Maria Rigamonti, Mother Maria Pierina, Cenacle Publishing, 1999

- ^ *Joan Carroll Cruz, OCDS. Saintly Men of Modern Times. (2003) ISBN 1931709777

- ^ Michael Freze, 1993, Voices, Visions, and Apparitions, OSV Publishing ISBN 087973454X page 57

- ^ Joan Carroll Cruz, 1984 Relics ISBN 0879737018 page 53

- ^ Matthew Bunson, 2004 OSV's encyclopedia of Catholic history ISBN 1592760260 page 912

- ^ Francis D'Emilio article on Pope John Paul II's visit to the Shroud of Turin, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette - May 25, 1998

- ^ Vatican website: Pope John Paul II's Address of May 24, 1998 in Turin Cathedral [7]

- ^ In Joseph Ratzinger, The spirit of Liturgy, cf. [8] and [9]

- ^ Catholic News Service

- ^ Catholic News Agency [10]

- ^ Vatican Radio

- ^ a b c d e Meacham, William. "The Authentication of the Turin Shroud: An Issue in Archaeological Epistemology". Retrieved 24 March 2010. [11]

- ^ Rogers, R.N. and Arnoldi, A.: "The Shroud of Turin: an amino-carbonyl reaction (Maillard reaction) may explain the image formation." In Ames, J.M. (Ed.): Melanoidins in Food and Health, Volume 4, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg, 2003, pp. 106–113. ISBN 92-894-5724-4

- ^ Alan A. Mills "Image formation on the Shroud of Turin", in Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 1995, vol. 20 No. 4, pp 319–326

- ^ Damon, P. E. (1989-02). "Radiocarbon dating of the Shroud of Turin". Nature. 337 (6208): 611–615. doi:10.1038/337611a0. Retrieved 2007-11-18.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ W.S.A. Dale, "The Shroud of Turin: Relic or Icon?" Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research B29 (1987) 187-192 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0168-583X(87)90233-3. This paper is significant in that it was presented to the international radiocarbon community shortly before radiocarbon dating was performed on the shroud.

- ^ Meacham, William (1 March 1986). "From the Proceedings of the Symposium "Turin Shroud - Image of Christ?"". Retrieved 14 April 2009.

- ^ J.A.Christen, Summarizing a Set of Radiocarbon Determinations: a Robust Approach. Appl. Statist. 43, No. 3, 489-503 (1994)

- ^ Rogers, Raymond N.: "Studies on the radiocarbon sample from the shroud of turin." Thermochimica Acta, Volume 425, Issue 1–2 (January 20, 2005), pages 189–194

- ^ Raymond N. Rogers, 2004, Studies on the radiocarbon sample from the shroud of turin, Thermochimica Acta 425 (2005) 189–194

- ^ "Dating The Shroud". Advanced Christianity. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- ^ Nickell, Joe. "Claims of Invalid "Shroud" Radiocarbon Date Cut from Whole Cloth". Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. Retrieved 2009-10-06. "Science has proved the Shroud of Turin a medieval fake, but defenders of authenticity turn the scientific method on its head by starting with the desired conclusion and working backward to the evidence—picking and choosing and reinterpreting as necessary."

- ^ Joe Nickell. "Claims of Invalid "Shroud" Radiocarbon Date Cut from Whole Cloth". Skeptical Inquirer. Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. Retrieved 2009-10-06.

- ^ Benford, Marino, "Discrepancies in the radiocarbon dating area of the Turin Shroud", Chemistry Today, vol. 26, 4, pp. 4-12,article

- ^ "turin shroud could be real saysscientist who originally said it was fake". mail-online. 2008-04-10. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ^ "Microbiology meets archaeology in a renewed quest for answers". Uthscsa.edu. 1998-05-08. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- ^ Ian Wilson, The Blood and the Shroud. New York: Free Press, 1998. ISBN 0684853590

- ^ "Debate of Roger Sparks and William Meacham on alt.turin-shroud". Shroud.com. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- ^ Walter C. McCrone: Judgment day for the Shroud of Turin. Amherst, N.Y., Prometheus Books, (1999) ISBN 1-57392-679-5

- ^ McCrone, W. C., Skirius, C., The Microscope, 28, 1980, pp 1-13; McCrone, W. C., The Microscope, 29, 1981, p. 19-38.

- ^ Ian Wilson, The Blood and the Shroud. New York: Free Press, 1998. pp. 80-81 ISBN 0684853590

- ^ Debunking The Shroud: Made by Human Hands

- ^ Wilson, p. 21-25

- ^ "DNA of Jesus-era shrouded man in Jerusalem reveals earliest case of leprosy". Physorg.com. December 16, 2009. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- ^ Bell, Bethany (December 16, 2009). "'Jesus-era' burial shroud found". BBC News. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- ^ "Shroud of Turin Not Jesus', Tomb Discovery Suggests". National Geographic Daily News. 12-19-2009. Retrieved 03-22-2010.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ [12]

- ^ The Sudarium of Oviedo

- ^ a b c "shroud of Turin". Skepdic.com. 2000-08-23. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- ^ Aldo Guerreschi and Michele Salcito IV Symposium Scientifique International, Paris 2002 Template:PDFlink

- ^ "Were particles of limestone dirt found on the Shroud of Turin?". Shroud Story. Retrieved 2010-02-27.

- ^ Ian Wilson, The Blood and the Shroud. New York: Free Press, 1998. ISBN 0684853590 page 328

- ^ see the final report of this commission: "La S. Sidon: Ricerche e studi della Commissione di Esperti." Diocesi Torinese, Turin, 1976

- ^ Evan Colins: A Question of Evidence. The Casebook of Great Forensic Controversies, from Napoleon to O.J. 2002, Chapter 1: The Turin Shroud (1355)

- ^ "Peter D'Adamo: ''Blood groups and the history of peoples.'' In: ''Complete Blood Type Encyclopedia.''". Dadamo.com. 1999-01-15. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- ^ Heller, J.H. and Adler, A.D.: "Blood on the Shroud of Turin." Applied Optics 19:2742–4 (1980)

- ^ Rogers, Raymond. "Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) by Raymond N. Rogers" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-06-15. "Several claims have been made that the blood has been found to be type AB, and claims have been made about DNA testing. We sent blood flecks to the laboratory devoted to the study of ancient blood at the State University of New York. None of these claims could be confirmed. The blood appears to be so old that the DNA is badly fragmented. Dr. Andrew Merriwether at SUNY has said that "... anyone can walk in off the street and amplify DNA from anything. The hard part is not to amplify what you don't want and only amplify what you want (endogenous DNA vs contamination)." It is doubtful that good DNA analyses can be obtained from the Shroud. It is almost certain that the blood spots are blood, but no definitive statements can be made about its nature or provenience, i.e., whether it is male and from the Near East."

- ^ Scandals and Follies of the 'Holy Shroud' | Skeptical Inquirer | Find Articles at BNET.com[dead link]

- ^ Baden, Michael. 1980. Quoted in Reginald W. Rhein, Jr., The Shroud of Turin: Medical examiners disagree. Medical World News, December 22, p. 50.

- ^ McCrone in Wiener Berichte uber Naturwissenschaft in der Kunst 1987/1988, 4/5, 50

- ^ Nickell, Joe: "Pollens on the 'shroud': A study in deception". Skeptical Inquirer, Summer 1994., pp 379–385

- ^ Jackson, John P., Eric J. Jumper, Bill Mottern, and Kenneth E. Stevenson. 1977. "The three-dimensional image of Jesus' burial cloth." Proceedings of the 1977 U.S. Conference of Research on the Shroud of Turin. Edit by Kenneth Stevenson, pp. 74-94. Bronx: Holy Shroud Guild.

- ^ Jean-Philippe Fontanille The coins of Pontius Pilate[dead link]

- ^ Heller, John H. Report on the Shroud of Turin. Houghton Mifflin, 1983. ISBN 0395339677 page 207

- ^ "Pressed Flowers". Shroud.com. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- ^ Nicholas P L Allen, Verification of the Nature and Causes of the Photo-negative Images on the Shroud of Lirey-Chambéry-Turin

- ^ Allen, Nicholas P. L.(1993) The methods and techniques employed in the manufacture of the Shroud of Turin. Unpublished DPhil thesis, University of Durban-Westville.

- ^ Allen, Nicholas P. L.(1993) Is the Shroud of Turin the first recorded photograph? The South African Journal of Art History, November 11, 23-32

- ^ Allen, Nicholas P. L.(1994)A reappraisal of late thirteenth-century responses to the Shroud of Lirey-Chambéry-Turin: encolpia of the Eucharist, vera eikon or supreme relic? The Southern African Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 4 (1),62-94

- ^ Allen, Nicholas P. L.(1998)The Turin Shroud and the Crystal Lens. Empowerment Technologies Pty. Ltd., - Port Elizabeth, South Africa

- ^ Craig, Emily A, Bresee, Randal R, Image Formation and the Shroud of Turin, Journal of Imaging Science and Technology, Volume 34, Number 1, 1994

- ^ Knights Templar hid the Shroud of Turin, says Vatican http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/faith/article6040521.ece

- ^ a b c d Turin Shroud 'could be genuine as carbon-dating was flawed' http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/newstopics/religion/5137163/Turin-Shroud-could-be-genuine-as-carbon-dating-was-flawed.html

- ^ Traces of Aramaic on Shroud of Turin

- ^ Phillip Pullella, "Italian scientist reproduces Shroud of Turin", Reuters, Mon Oct 5, 2009 11:30am EDT

- ^ http://shroudofturin.wordpress.com/2009/10/09/why-the-italian-fake-does-not-reproduce-the-shroud-of-turin/

- ^ "Death certificate is imprinted on the Shroud of Turin, says Vatican scholar", Times of London, Richard Owen, 21 November 2009 [13]

- ^ "'Jesus-Era' Burial Shroud Found", Bethany Bell, BBC News, 16 December 2009 [14]

- ^ The Ancient Jewish Shroud At Turin by John N. Lupia, Regina Caeli Press, 2010; ISBN 978-0-9826739-0-4

- ^ Marco Riani, Anthony C. Atkinson, Fabio Crosilla, and Giulio Fanti, "A Robust Statistical Analysis of the 1988 Turin Shroud Radiocarbon Dating Results", Robust Statistical Analysis of the 1988 Turin Shroud Radiocarbon Dating Results. International Workshop on the Scientific Approach to the Acheiropoietos Images, ENEA Resarch Center of Frascati (Italy), 4-5–6 May 2010.

Further reading

- Arthur Barnes, 2003 Holy Shroud of Turin Kessinger Press ISBN 0766134253

- Baima Bollone, P., La Sindone-Scienza e Fide 1981, 169–179.

- Baime Bollone, P., Jorio, M., Massaro, A.L., Sindon 23, 5, 1981.

- Baima Bollone, Jorio, M., Massaro, A.L., Sindon 24, 31, 1982, pp 5–9.

- Baima Bollone, P., Gaglio, A. Sindon 26, 33, 1984, pp 9–13.

- Baima Bollone, P., Massaro, A.L. Shroud Spectrum 6, 1983, pp 3–6.

- Damascene, John: On Holy Images [15].

- Guscin, Mark: "The 'Inscriptions' on the Shroud." British Society for the Turin Shroud Newsletter, November 1999.

- Kersten, H., Gruber, E.R., 1992. The Jesus Conspiracy: Turin Shroud and the Truth about the Resurrection (Paperback) ISBN 1852306661.

- Lombatti, Antonio: "Doubts Concerning the Coins over the Eyes." British Society for the Turin Shroud Newsletter, Issue 45, 1997.

- Marino, Joseph G. and Benford, M. Sue. Evidence for the Skewing of the C-14 Dating of the Shroud of Turin due to Repairs. Sindone 2000 Conference, Orvieto, Italy. Template:PDFlink

- Mills, A.A.: "Image formation on the Shroud of Turin" Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, Vol. 20, 1995

- McCrone, W. C., The Microscope, 29, 1981, p. 19–38.

- McCrone, W. C., Skirius, C., The Microscope, 28, 1980, pp 1–13.

- Nickell, Joe: "Scandals and Follies of the 'Holy Shroud'." Skeptical Inquirer, September 2001. [16]

- Picknett, Lynn and Prince, Clive: The Turin Shroud: In Whose Image?, Harper-Collins, 1994 ISBN 0-552-14782-6.

- Silverton, Julia. Decoding the Past: The Shroud of Turin, 2005 History Channel video documentary, produced by John Joseph.* Stevenson, Kenneth E., Gary R. Habermas: "Verdict on the Shroud", Servant Books, 1981 ISBN 0-89283-111-1

- Tribbe, Frank C.: Portrait of Jesus: The Shroud of Turin in Science and History, Paragon House, 2006 ISBN 1-557788545

- Whiting, Brendan, 2006, The Shroud Story, Harbour Publishing, ISBN 064645725X

- Wilson, N.D.: "Father Brown Fakes the Shroud", Books & Culture, March-April 2005, pp. 22–29.

- Zugibe, Frederick: "The Man of the Shroud was Washed." Sindon N.S. Quad. 1, June 1989.

External links

- Official site of the custodians of the Shroud in Turin

- The Shroud of Turin through History - A photographic slideshow history of the shroud at Discovery.com

- Discovery of image on reverse side of shroud (The Guardian)

- Jesus' Shroud? Recent Findings Renew Authenticity Debate by National Geographic Society

- Photo in the News: Shroud of Turin by National Geographic Society

- Shroud Science Group's Shroud of Turin Wiki

- Online Length Measurements on Shroud Photographs

Pro-authenticity sites

- Shroud.com

- Speech by Pope John Paul about the Shroud

- "Shroud of Christ?" (A "Secrets of the Dead" episode on PBS)

- Authenticity of the Shroud

- "Forensic Medicine and the Shroud of Turin"

- Shroud of Turin Story - Guide to the Facts

- Relationship of Shroud of Turin to the Volto Santo

- Shroud University - Explore the Mystery

- Sindonology.org

- Shroud Exhibit and Museum (SEAM), Inc. website for the museum in Alamogordo, NM

- William Meacham, "The Authentication of the Turin Shroud: An Issue in Archaeological Epistemology" in Current Anthropology, Vol. 24, No 3 (June 1983), with reactions by other scientists, pro and contra

Skeptical sites

- Shroud of Turin, sacred relic or religious hoax?

- McCrone Research Institute presentation of its findings Assertion that the shroud is a painting.

- The Skeptical Shroud of Turin Website

- News on the Shroud of Turin: Purpura-dye as a light sensitive layer? German, with an English summary.

- The shroud of Turin - The Skeptic's Dictionary

45°04′23″N 07°41′09″E / 45.07306°N 7.68583°E

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

- Articles that may be too long from March 2010

- Wikipedia neutral point of view disputes from March 2010

- Articles needing cleanup from March 2010

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from March 2010

- Wikipedia pages needing cleanup from March 2010

- Relics associated with Jesus

- Alleged tombs of Jesus

- Visitor attractions in Turin

- Culture in Turin

- Christian terms