History of Cambodia: Difference between revisions

| Line 117: | Line 117: | ||

{{Wikipedia-Books|Cambodia}} |

{{Wikipedia-Books|Cambodia}} |

||

{{sisterlinks|Cambodia}} |

{{sisterlinks|Cambodia}} |

||

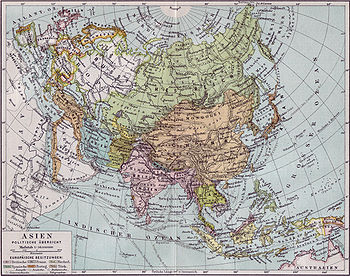

{{History of Asia}} |

|||

*[[History of Buddhism in Cambodia]] |

*[[History of Buddhism in Cambodia]] |

||

*[[Economic history of Cambodia]] |

*[[Economic history of Cambodia]] |

||

Revision as of 01:21, 15 April 2010

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2008) |

| History of Cambodia |

|---|

| Early history |

| Post-Angkor period |

| Colonial period |

| Independence and conflict |

| Peace process |

| Modern Cambodia |

| By topic |

|

|

Carbon 14 dating of a cave at Laang Spean in northwest Cambodia reveals people who made pots were living in Camboda as early as 4200 B.C.E. (Before the Common Era).[1] Further archaeological evidence indicates that other parts of the region now called Cambodia were inhabited from around 1000-2000 B.C.E. by a Neolithic culture. Skulls and human bones found at Samrong Sen date from 1500 B.C.E.[2] These people may have migrated from South Eastern China to the Indochinese Peninsula, although some scholars maintain they may have come from India.[3] Scholars trace the first cultivation of rice and the first bronze making in Southeast Asia to these people.[4] By the first century CE, the inhabitants had developed relatively stable, organized societies and spoke languages very much related to the Cambodian or Khmer of the present day.[5] The culture and technical skills of thse people of the first century in the Common Era far surpassed the primitive stage. The most advanced groups lived along the coast and in the lower Mekong River valley and delta regions in houses constructed on stilts where they cultivated rice, fished and kept domesticated animals. Recent research has unlocked the discovery of artificial circular earthworks dating to Cambodia's Neolithic era.1 The Khmer people were one of the first inhabitants of South East Asia. They were also among the first in South East Asia to adopt religious ideas and political institutions from India and to establish centralized kingdoms surrounding large territories. The earliest known kingdom in the area, Funan, flourished from around the first to the sixth century AD. This was succeeded by Chenla, which controlled large parts of modern Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand.

Funan Empire: 68-550

The Funanese Empire rose to eminence from its affluent and powerful home city of Oc Eo (in nowadays Vietnam), known in the Roman Empire as Kattigara, meaning the Renowned City. Contacts with the distant Roman Empire are evidenced by the fact that Roman coins have been found at archeological sites dating from the second and third centuries.[6] However, most of the foreign trade of the Funan Empire, however, was carried on much closer to home—with India, especially the Bengal area of India. Trade with India commenced well before 500 B.C.E (before the widespread use of Sanskrit as a language in India).[7] With the Indian trade came the Indianization of the culture of Funan and the religion of Hinduism. Funan and its succeeding societies which occupied this section of Southeast Asia would remain Hindu in religion for about 900 years. Some cultural features would last much longer. To this day the modern Cambodians eat with spoons and their fingers in the Indian manner rather than chop sticks like many other Chinese-influenced cultures of southeast Asia.[8]

The empire reached its greatest extent under the rule of Fan Shih-man in the early third century C.E., extending as far south as Malaysia and as far west as Burma. The Funanese established a strong system of mercantilism and commercial monopolies that would become a pattern for empires in the region. Exports from the Funan Empire were largely forest products and precious metals—including gold elephants, ivory, rhinoceros horn, kingfisher feathers, wild spices like cardamom, lacquer hides and aromatic wood.[9] Fan Shih-man expanded the fleet and improved the Funanese bureaucracy, creating a quasi-feudal pattern that left local customs and identities largely intact, particularly in the empire's farther reaches.

Chenla: 550-802

The Khmers, vassals of Funan had reached the Mekong River from the northern Menam River via the Mun River Valley. Chenla, their first independent state developed out of Funanese influence.

Ancient Chinese records mention two kings, Shrutavarman and Shreshthavarman who ruled at the capital Shreshthapura located in modern day southern Laos. The immense influence on the identity of Cambodia to come was wrought by the Khmer Kingdom of Bhavapura, in the modern day Cambodian city of Kompong Thom. Its legacy was its most important sovereign, Ishanavarman who completely conquered the kingdom of Funan during 612-628. He chose his new capital at the Sambor Prei Kuk, naming it Ishanapura.

After the death of Jayavarman I in 681, turmoil came upon the kingdom and at the start of the 8th century, the kingdom broke up into many principalities. Pushkaraksha, the ruler of Shambhupura announced himself as king of the entire Kambuja. Chinese chronicles proclaim that in the 8th century, Chenla was split into land Chenla and water Chenla. During this time, Shambhuvarman son of Pushkaraksha controlled most of water Chenla until the 8th century which the Malayans and Javanese dominated over many Khmer principalities.

Khmer Empire: 802-1431

The golden age of Khmer civilization, however, was the period from the ninth to the thirteenth centuries, when the kingdom of Kambuja, which gave Kampuchea, or Cambodia, its name, ruled large territories from its capital in the region of Angkor in western Cambodia.

Legend has it that in 802 C.E., Jayavarman II, king of the Khmers, first came to the Kuhlen hills, the future site of Angkor Wat.[10] Later, under Jayavarman VII (1181–ca. 1218), Khmer or Kambuja reached its zenith of political power and cultural creativity. Jayavarman VII gained power and territory in a series of successful wars. Khmer conquests were almost unstoppable as they raided home cities of powerful seafaring Chams. However, territorial expansion stopped after a defeat by Dai Viet. The battle also witnessed Suryavarman II's death. Following Jayavarman VII's death, Kambuja experienced a gradual decline. Important factors were the aggressiveness of neighboring peoples (especially the Thai, or Siamese), chronic interdynastic strife, and the gradual deterioration of the complex irrigation system that had ensured rice surpluses. The Angkorian monarchy survived until 1431, when the Thai captured Angkor Thom and the Cambodian king fled to the southern part of the country.

Dark Ages: 1618-1863

The fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries were a period of continued decline and territorial loss. Cambodia enjoyed a brief period of prosperity during the sixteenth century because its kings, who built their capitals in the region southeast of the Tonle Sap along the Mekong River, promoted trade with other parts of Asia. This was the period when Spanish and Portuguese adventurers and missionaries first visited the country. However, the Thai conquest of the new capital at Lovek in 1594 marked a downturn in the country's fortunes and Cambodia. Becoming a pawn in power struggles between its two increasingly powerful neighbors, Siam and Vietnam. Cambodia remained a protectorate of Siam. Vietnam's settlement of the Mekong Delta led to its annexation of that area at the end of the seventeenth century. Vietnam employed a strategy similar to those of North American pilgrims and pioneers: settle and claim. Such foreign encroachments continued through the first half of the nineteenth century. A successful invasion by Vietnam further limited Thai protectorship in Cambodia and established the kingdom under full Vietnamese suzerainty.

French colonial period: 1863-1953

In 1863, King Norodom signed an agreement with the French to establish a protectorate over his kingdom. The state gradually came under French colonial domination.

During World War II, the Japanese allowed the French government (based at Vichy) that collaborated with the republican opponents and attempted to negotiate acceptable terms for independence from the French.

Cambodia's situation at the end of the war was chaotic. The Free French, under General Charles de Gaulle, were determined to recover Indochina, though they offered Cambodia and the other Inchochinese protectorates a carefully circumscribed measure of self-government. Convinced that they had a "civilizing mission," they envisioned Indochina's participation in a French Union of former colonies that shared the common experience of French culture.

Sihanouk's "royal crusade for independence" resulted in grudging French acquiescence to his demands for a transfer of sovereignty. A partial agreement was struck in October 1953. Sihanouk then declared that independence had been achieved and returned in triumph to Phnom Penh.

First administration of Sihanouk: 1955-1970

As a result of the Geneva Conference on Indochina, Cambodia was able to bring about the withdrawal of the Viet Minh troops from its territory and to withstand any residual impingement upon its sovereignty by external powers.

Neutrality was the central element of Cambodian foreign policy during the 1950s and 1960s. By the mid-1960s, parts of Cambodia's eastern provinces were serving as bases for North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong (NVA/VC) forces operating against South Vietnam, and the port of Sihanoukville was being used to supply them. As NVA/VC activity grew, the United States and South Vietnam became concerned, and in 1969, the United States began a fourteen month long series of bombing raids targeted at NVA/VC elements, contributing to destabilization. Prince Sihanouk, fearing that the conflict between communist North Vietnam and South Vietnam might spill over to Cambodia, steadfastly opposed the bombing campaign by the United States along the Vietnam-Cambodia border and inside Cambodian territory. Prince Sihanouk wanted Cambodia to stay out of the North Vietnam-South Vietnam conflict and was very critical of the United States government and its allies (the South Vietnamese government). The United States claims that the bombing campaign took place no further than ten, and later twenty miles (32 km) inside the Cambodian border, areas where the Cambodian population had been evicted by the NVA.[11] Prince Sihanouk, facing internal struggles of his own, due to the rise of the Khmer Rouge, did not want Cambodia to be involved in the conflict. Sihanouk wanted the United States and its allies (South Vietnam) to keep the war away from the Cambodian border. Not only did Sihanouk try to keep the communist North Vietnamese soldiers from entering Cambodia territory, but he also did not allow the United States to use Cambodian air space and airports for military purposes. This upset the United States greatly. The United States saw Prince Sihanouk as a North Vietnamese sympathizer and a thorn on the United States, and using the CIA, it began plans to get rid of Sihanouk.[12]

Throughout the 1960s, domestic Cambodian politics became polarized. Opposition to the government grew within the middle class and leftists including Paris-educated leaders like Son Sen, Ieng Sary, and Saloth Sar (later known as Pol Pot), who led an insurgency under the clandestine Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK). Sihanouk called these insurgents the Khmer Rouge, literally the "Red Khmer." But the 1966 national assembly elections showed a significant swing to the right, and General Lon Nol formed a new government, which lasted until 1967. During 1968 and 1969, the insurgency worsened. In August 1969, Lon Nol formed a new government. Prince Sihanouk went abroad for medical reasons in January 1970.

The Khmer Republic and the War: 1970-1975

In March 1970, while Prince Sihanouk was absent, General Lon Nol deposed Prince Sihanouk in a coup d'état in the early hours of March 18, 1970.[13] It has been alleged that this coup was not planned by the United States Central Intelligence Agency.[14][citation needed] Still while abroad, Prince Sihanouk had been warned by both the leaders in Soviet Union and in Peking, that he should return home, immediately without delay.[15] As early as March 12, 1970, the C.I.A. Station Chief told Washington that based on communications from Sirik Matak, Lon Nol's cousin, that "the (Cambodian) army was ready for a coup."[16] Nonetheless, Lon Nol assumed the power after the military coup and immediately allied Cambodia with the United States. Immediately, Son Ngoc Thanh, an opponent of Pol Pot, announced his support for the new government. On October 9, the Cambodian monarchy was abolished, and the country was renamed the Khmer Republic.

Hanoi rejected the new republic's request for the withdrawal of NVA troops. 2,000–4,000 Cambodians who had gone to North Vietnam in 1954 reentered Cambodia, backed by North Vietnamese soldiers. In response, the United States moved to provide material assistance to the new government's armed forces, which were engaged against both CPK insurgents and NVA forces.

O n April 1970, US President Nixon announced to the American public that US and South Vietnamese ground forces had entered Cambodia in a campaign aimed at destroying NVA base areas in Cambodia (see Cambodian Incursion).[17] The US had already been bombing Cambodia for well over a year by that point.

Although a considerable quantity of equipment was seized or destroyed by US and South Vietnamese forces, containment of North Vietnamese forces proved elusive. The North Vietnamese moved deeper into Cambodia to avoid US and South Vietnamese raids. NVA units overran many Cambodian army positions while the CPK expanded their small-scale attacks on lines of communication.

The Khmer Republic's leadership was plagued by disunity among its three principal figures: Lon Nol, Sihanouk's cousin Sirik Matak, and National Assembly leader In Tam. Lon Nol remained in power in part because none of the others were prepared to take his place. In 1972, a constitution was adopted, a parliament elected, and Lon Nol became president. But disunity, the problems of transforming a 30,000-man army into a national combat force of more than 200,000 men, and spreading corruption weakened the civilian administration and army.

The Communist insurgency inside Cambodia continued to grow, aided by supplies and military support from North Vietnam. Pol Pot and Ieng Sary asserted their dominance over the Vietnamese-trained communists, many of whom were purged. At the same time, the Communist Party of Kampuchea forces became stronger and more independent of their Vietnamese patrons. By 1973, the CPK were fighting battles against government forces with little or no North Vietnamese troop support, and they controlled nearly 60% of Cambodia's territory and 25% of its population.

The government made three unsuccessful attempts to enter into negotiations with the insurgents, but by 1974, the CPK were operating openly as divisions, and some of the NVA combat forces had moved into South Vietnam. Lon Nol's control was reduced to small enclaves around the cities and main transportation routes. More than 2 million refugees from the war lived in Phnom Penh and other cities.

On New Year's Day 1975, Communist troops launched an offensive which, in 117 days of the hardest fighting of the war, collapsed the Khmer Republic. Simultaneous attacks around the perimeter of Phnom Penh pinned down Republican forces, while other CPK units overran fire bases controlling the vital lower Mekong resupply route. A US-funded airlift of ammunition and rice ended when Congress refused additional aid for Cambodia. The Lon Nol government in Phnom Penh surrendered on April 17, 1975, just five (5) days after the US mission evacuated Cambodia.[18]

Democratic Kampuchea (the Khmer Rouge/Red Khmer age): 1975-1979

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2008) |

Immediately after its victory, the CPK ordered the evacuation of all cities and towns, sending the entire urban population into the countryside to work as farmers, as the CPK was trying to reshape society into a model that Pol Pot had conceived.

Thousands starved or died of disease during the evacuation and its aftermath. Many of those forced to evacuate the cities were resettled in newly created villages, which lacked food, agricultural implements, and medical care. Many who lived in cities had lost the skills necessary for survival in an agrarian environment. Thousands starved before the first harvest. Hunger and malnutrition—bordering on starvation—were constant during those years. Most military and civilian leaders of the former regime who failed to disguise their pasts were executed.

Within the CPK, the Paris-educated leadership—Pol Pot, Ieng Sary, Nuon Chea, and Son Sen—were in control. A new constitution in January 1976 established Democratic Kampuchea as a Communist People's Republic, and a 250-member Assembly of the Representatives of the People of Kampuchea (PRA) was selected in March to choose the collective leadership of a State Presidium, the chairman of which became the head of state.

Prince Sihanouk resigned as head of state on April 4. On April 14, after its first session, the PRA announced that Khieu Samphan would chair the State Presidium for a 5-year term. It also picked a 15-member cabinet headed by Pol Pot as prime minister. Prince Sihanouk was put under virtual house arrest.

The new government sought to completely restructure Cambodian society. Remnants of the old society were abolished and religion, particularly Buddhism and Catholicism, was suppressed. Agriculture was collectivized, and the surviving part of the industrial base was abandoned or placed under state control. Cambodia had neither a currency nor a banking system.

Life in 'Democratic Kampuchea' was strict and brutal. In many areas of the country people were rounded up and executed for speaking a foreign language, wearing glasses, scavenging for food, and even crying for dead loved ones. Former businessmen and bureaucrats were hunted down and killed along with their entire families; the Khmer Rouge feared that they held beliefs that could lead them to oppose their regime. A few Khmer Rouge loyalists were even killed for failing to find enough 'counter-revolutionaries' to execute.

Solid estimates of the numbers who died between 1975 and 1979 are not available, but it is likely that hundreds of thousands were executed by the regime. Hundreds of thousands died of starvation and disease (both under the CPK and during the Vietnamese invasion in 1978). Some estimates of the dead range from 1 to 3 million, out of a 1975 population estimated at 7.3 million. The CIA estimated 50,000–100,000 were executed and 1.2 million died from 1975 to 1979.[19]

Democratic Kampuchea's relations with Vietnam and Thailand worsened rapidly as a result of border clashes and ideological differences. While communist, the CPK was fiercely nationalistic, and most of its members who had lived in Vietnam were purged. Democratic Kampuchea established close ties with the People's Republic of China, and the Cambodian-Vietnamese conflict became part of the Sino-Soviet rivalry, with Moscow backing Vietnam. Border clashes worsened when the Democratic Kampuchea military attacked villages in Vietnam. The regime broke off relations with Hanoi in December 1977, protesting Vietnam's alleged attempt to create an Indochina Federation. In mid-1978, Vietnamese forces invaded Cambodia, advancing about 30 miles (48 km) before the arrival of the rainy season.

The reasons for Chinese support of the CPK was to prevent a pan-Indochina movement, and maintain Chinese military superiority in the region. The Soviet Union supported a strong Vietnam to maintain a second front against China in case of hostilities and to prevent further Chinese expansion. Since Stalin's death, relations between Mao-controlled China and the Soviet Union had been lukewarm at best. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, China and Vietnam would fight the brief Sino-Vietnamese War over the issue.

In December 1978, Vietnam announced formation of the Kampuchean United Front for National Salvation (KUFNS) under Heng Samrin, a former DK division commander. It was composed of Khmer Communists who had remained in Vietnam after 1975 and officials from the eastern sector—like Heng Samrin and Hun Sen—who had fled to Vietnam from Cambodia in 1978. In late December 1978, Vietnamese forces launched a full invasion of Cambodia, capturing Phnom Penh on January 7, 1979 and driving the remnants of Democratic Kampuchea's army westward toward Thailand.

People's Republic of Kampuchea (Vietnamese occupation): 1979-1993

On January 10, 1979, Communist Vietnam installed Heng Samrin as head of state in the new People's Republic of Kampuchea (PRK). The Vietnamese army continued its pursuit of Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge forces. At least 600,000 Cambodians displaced during the Pol Pot era and the Vietnamese invasion began streaming to the Thai border in search of refuge. The international community responded with a massive relief effort, for these refugees only, coordinated by the United States through UNICEF and the World Food Program. More than $400 million was provided between 1979 and 1982, including major contributions from Vietnam and other Eastern Bloc countries as well as the United States. At one point, more than 500,000 Cambodians were living along the Thai and Cambodian border and more than 100,000 in holding centers inside Thailand.

Modern Cambodia: 1993-Present

On October 23, 1991, the Paris Conference reconvened to sign a comprehensive settlement giving the UN full authority to supervise a cease-fire, repatriate the displaced Khmer along the border with Thailand, disarm and demobilize the factional armies, and prepare the country for free and fair elections. Prince Sihanouk, President of the Supreme National Council of Cambodia (SNC), and other members of the SNC returned to Phnom Penh in November 1991, to begin the resettlement process in Cambodia. The UN Advance Mission for Cambodia (UNAMIC) was deployed at the same time to maintain liaison among the factions and begin demining operations to expedite the repatriation of approximately 370,000 Cambodians from Thailand.

On March 16, 1992, the UN Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) arrived in Cambodia to begin implementation of the UN Settlement Plan. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees began fullscale repatriation in March 1992. UNTAC grew into a 22,000-strong civilian and military peacekeeping force to conduct free and fair elections for a constituent assembly.

Over 4 million Cambodians (about 90% of eligible voters) participated in the May 1993 elections, although the Khmer Rouge or Party of Democratic Kampuchea (PDK), whose forces were never actually disarmed or demobilized, barred some people from participating. Prince Ranariddh's royalist FUNCINPEC Party was the top vote recipient with 45.5% of the vote, followed by Hun Sen's Cambodian People's Party and the Buddhist Liberal Democratic Party, respectively. FUNCINPEC then entered into a coalition with the other parties that had participated in the election. The parties represented in the 120-member assembly proceeded to draft and approve a new constitution, which was promulgated September 24, 1993. It established a multiparty liberal democracy in the framework of a constitutional monarchy, with the former Prince Sihanouk elevated to King. Prince Ranariddh and Hun Sen became First and Second Prime Ministers, respectively, in the Royal Cambodian Government (RGC). The constitution provides for a wide range of internationally recognized human rights.

On October 4, 2004, the Cambodian National Assembly ratified an agreement with the United Nations on the establishment of a tribunal to try senior leaders responsible for the atrocities committed by the Khmer Rouge. Donor countries have pledged the $43 million international share of the three-year tribunal budget, while the Cambodian government’s share of the budget is $13.3 million. The tribunal started trials of senior Khmer Rouge leaders in 2008.

See also

References

Constructs such as ibid., loc. cit. and idem are discouraged by Wikipedia's style guide for footnotes, as they are easily broken. Please improve this article by replacing them with named references (quick guide), or an abbreviated title. (March 2010) |

- ^ David Chandler, A History of Cambodia (Westview Publishers: Boulder Colorado, 2008) p. 13.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ David Chandler, A History of Camboida, p. 19.

- ^ Percival Spear, India: A Modern History (University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, 1961) p. 14.

- ^ David Chandler, A History of Cambdia, p. 16.

- ^ David Chandler, A History of Cambodia (Westview Publishing: Boulder, Colorado, 2008) p. 19.

- ^ Ibid., p. 39.

- ^ Davidson, Phillip B. Vietnam at War: The History 1946–1975. 1988. P. 593

- ^ Stearns, Peter N. (ed.). Encyclopedia of World History (6th ed.). The Houghton Mifflin Company/Bartleby.com.

P. 1012

- ^ Philip Short, Pol Pot: Anatomy of a Nightmare p. 197.

- ^ Philip Short, Pol Pot: Anatomy of a Nightmare (Henry Holt & Co.: New York, 2004) p. 196.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid., p. 195.

- ^ Ibid., p. 204.

- ^ Philip Short, Pol Pot: Anatomy of a Nightmare p. 4.

- ^ "The Cambodian Genocide Program". Genocide Studies Program. Yale University. 1994–2008. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link)

<references >

- Cambodia

This image is available from the United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division under the digital ID {{{id}}}

This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Wikipedia:Copyrights for more information.

This article incorporates public domain material from U.S. Bilateral Relations Fact Sheets. United States Department of State. - [1]

This article incorporates public domain material from U.S. Bilateral Relations Fact Sheets. United States Department of State. - [1]

External links

- State Department Background Note: Cambodia

- Summary of UNTAC mission