The Handmaid's Tale (film): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

==Cast== |

==Cast== |

||

{{col-begin}} |

|||

{{col-break}} |

|||

*[[Natasha Richardson]] as Kate / Offred |

*[[Natasha Richardson]] as Kate / Offred |

||

*[[Robert Duvall]] as Commander |

*[[Robert Duvall]] as Commander |

||

Revision as of 15:59, 28 October 2010

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2010) |

| The Handmaid's Tale | |

|---|---|

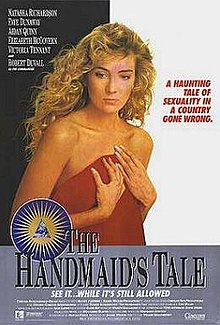

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Volker Schlöndorff |

| Written by | Novel: Margaret Atwood Screenplay: Harold Pinter |

| Produced by | Daniel Wilson |

| Starring | Natasha Richardson Faye Dunaway Robert Duvall Aidan Quinn Elizabeth McGovern |

| Cinematography | Igor Luther |

| Edited by | David Ray |

| Music by | Ryuichi Sakamoto |

| Distributed by | Metro Goldwyn Mayer |

Release date | February 15, 1990 |

Running time | 109 minutes |

| Country | Template:Film US |

| Language | English |

| Budget | N/A |

The Handmaid's Tale is a 1990 film adaptation of the Margaret Atwood novel of the same name. Directed by Volker Schlöndorff the film stars Natasha Richardson (Kate/Offred), Faye Dunaway (Serena Joy), Robert Duvall (The Commander, Fred), Aidan Quinn (Nick), and Elizabeth McGovern (Moira). The screenplay was written by Harold Pinter. The original music score was composed by Ryuichi Sakamoto. MGM Home Entertainment released an Avant-Garde Cinema DVD of the film in 2001.

Plot summary

In the near future, as war rages across the fictional Republic of Gilead and pollution has rendered 99 percent of the female population sterile, Kate (Offred in the novel), sees her husband killed and her daughter kidnapped while trying to escape across the border to Canada. Kate herself is transformed into a Handmaid; a concubine for one of the privileged but barren couples who run the country's religious fundamentalist regime. Although she resists being indoctrinated into the bizarre cult of the Handmaids, which mixes the Old Testament orthodoxy and misogynist cant with 12-step gospel and ritualized violence, Kate soon finds herself in the home of the Commander and his obdurate wife, Serena Joy.

Forced to lie between Serena Joy's legs and be sexually penetrated each month by the Commander, Kate longs for her earlier life. She soon learns that since many of the nation's powerful men are as sterile as their wives, she will have to risk the punishment for fornication — death by hanging — in order to be fertilized by another man who can provide her with the pregnancy that has become her sole raison d'être. The other man is Nick, the Commander's sympathetic driver. Kate grows attached to him and eventually pregnant with his child. Only the affiliation of her fellow handmaid, Ofglen, seems to offer any chance of giving her unborn child a life of freedom or finding the daughter she already lost.

Cast

- Natasha Richardson as Kate / Offred

- Robert Duvall as Commander

- Faye Dunaway as Serena Joy

- Elizabeth McGovern as Moira

- Aidan Quinn as Nick

- Victoria Tennant as Aunt Lydia

- Blanche Baker as Ofglen

- Traci Lind as Janine / Ofwarren

- Zoey Wilson as Aunt Helena

- Kathryn Doby as Aunt Elizabeth

- Reiner Schöne as Luke

- Lucia Hartpeng as Cora

- Karma Ibsen Riley as Aunt Sara

- Lucile McIntyre as Rita

- Gary Bullock as Officer on Bus

- Allison Holmes, June

- J. Michael Hunter as Preacher

- Robert D. Raiford as Dick

- Mirjam Bohnet as Alma

- Julian Bell as TV Announcer #1

- David Barnes as Guard

- James A. Carleo III as Angel at Desk

- Jim Grimshaw as Eye in Van

- Ivan H. Migel as Eye

| class="col-break " |

- Doris Boggs as Aunt

- Annemarie Fenske as Aunt Christina

- Linda Pierce as Wife #2

- Nina Lynn Blanton as Wife #3

- Rhesa Reagan Stone as Mrs. Warren

- Sara Seidman as Handmaid

- Muse Watson as Guardian

- Janell McLeod as Martha

- Elke Ritschel as Hostess

- Jane Learned as Nun

- Randell Haynes as Condemned Man

- Rhonda Bond as Black Woman

- Mil Nicholson as Wardress

- Robert Pentz as Guard #1

- Tom McGovern as Guard #2

- Danny Simpkins as Waiter

- James Martin Jr. as Steve

- Stefanie J. Chen as Ofglen #2

- Ed Grady as Old Man

- Molly Sandick as Baby

- Blair Struble as Jill

- Bill Owen as TV Announcer #2

- David Dukes as Doctor

- Rob McGowan as Street Worker

|}

Differences between novel and film

This section possibly contains original research. (March 2009) |

In the book, the Handmaids wear loose-fitting garments that obscure all of their body and allow them no peripheral vision, whereas in the film, the Handmaids wear knee-length red dresses and not as much head covering. The producers explain that this change was a result of the film's small budget. The Handmaid dresses were off-the-rack dresses ordered from Sears. While the novel was a bestseller, there was not much interest from Hollywood to make a film, and the budget was low. Despite the apparent appeal of a meaty role such as that of playing Offred, mainstream actresses showed no interest in starring in the film, due to Offred's passivity, so a much lower-profiled actress, Natasha Richardson, was chosen for the lead (Johnson [page no.?]).[1]

- Book: Offred's name: unknown (suggested to be "June" at the end of the first chapter)

- Film: Offred's name: Kate

- Book: Pregnant handmaid enters the shop the two handmaids are in and the pregnant Handmaid is admired by everybody.

- Film: Pregnant woman enters a car in front of the shop and is applauded.

- Film: Offred actively helps Moira to flee.

- Film: Offred wants to flee/escape together with Nick. Offred is going to bear a child for Nick.

- Film: Commander wants Offred to commit suicide when Serena Joy finds out that the Commander has been seeing Offred in private. Offred kills the Commander by using a knife. She received it from the underground organization; Nick is a member of the underground organization, and Offred receives a letter from Nick occasionally.

- Book: Nick stays to help the underground organization.

- Film: They flee, pretending they are caught by the Angels/Guards.

- Book: Open ending

- Film: Ending shows Offred away and lonely in the mountains. She is pregnant.

Pinter's unpublished filmscript

According to Steven H. Gale, in his book Sharp Cut, "the final cut of The Handmaid's Tale is less a result of Pinter's script than any of his other films. He contributed only part of the screenplay: reportedly he 'abandoned writing the screenplay from exhaustion.' … Although he tried to have his name removed from the credits because he was so displeased with the movie (in 1994 he told me that this was due to the great divergences from his script that occur in the movie), … his name remains as screenwriter" (318).

Gale observes further that "while the film was being shot, director Volker Schlondorff", who had replaced the original director Karel Reisz, "called Pinter and asked for some changes in the script"; however, "Pinter recall[ed] being very tired at the time, and he suggested that Schlondorff contact Atwood about the rewrites. He essentially gave the director and author carte blanche to accept whatever changes that she wanted to institute, for, as he reasoned, 'I didn't think an author would want to fuck up her own work.' … As it turned out, not only did Atwood make changes, but so did many others who were involved in the shoot" (318). Gale points out that Pinter told his biographer Michael Billington that

It became … a hotchpotch. The whole thing fell between several shoots. I worked with Karel Reisz on it for about a year. There are big public scenes in the story and Karel wanted to do them with thousands of people. The film company wouldn't sanction that so he withdrew. At which point Volker Schlondorff came into it as director. He wanted to work with me on the script, but I said I was absolutely exhausted. I more or less said, 'Do what you like. There's the script. Why not go back to the original author if you want to fiddle about?' He did go to the original author. And then the actors came into it. I left my name on the film because there was enough there to warrant it—just about. But it's not mine' ([Pinter, as qtd. in Harold Pinter] 304). (Gale, Sharp Cut 318–19)

In an essay on Pinter's screenplay for The French Lieutenant's Woman, in The Films of Harold Pinter, Gale discusses Pinter's "dissatisfaction with" the "kind of alteration" that occurs "once the script is tinkered with by others" and "it becomes collaborative to the point that it is not his product any more or that such tinkering for practical purposes removes some of the artistic element" (73); he adds: "Most notably The Handmaid's Tale, which he considered so much altered that he has refused to allow the script to be published, and The Remains of the Day, which he refused to allow his name to be attached to for the same reason …" (84n3).[2]

Christopher C. Hudgins discusses further details about why "Pinter elected not to publish three of his completed filmscripts, The Handmaid's Tale, The Remains of the Day, and Lolita," all of which Hudgins considers "masterful filmscripts" of "demonstrable superiority to the shooting scripts that were eventually used to make the films"; fortunately ("We can thank our various lucky stars"), he says, "these Pinter filmscripts are now available not only in private collections but also in the Pinter Archive at the British Library"; in this essay, which he first presented as a paper at the 10th Europe Theatre Prize symposium, Pinter: Passion, Poetry, Politics, held in Turin, Italy, in March 2006, Hudgins "examin[es] all three unpublished filmscripts in conjunction with one another" and "provides several interesting insights about Pinter's adaptation process" (132).

Richardson's perspective on the script

In a retrospective account written after Natasha Richardson's death, for CanWest News Service, Jamie Portman cites Richardson's view of the difficulties involved with making Atwood's novel into a film script:

Richardson recognized early on the difficulties in making a film out of a book which was "so much a one-woman interior monologue" and with the challenge of playing a woman unable to convey her feelings to the world about her, but who must make them evident to the audience watching the movie. … She thought the passages of voice-over narration in the original screenplay would solve the problem, but then Pinter changed his mind and Richardson felt she had been cast adrift. … "Harold Pinter has something specific against voice-overs," she said angrily 19 years ago. "Speaking as a member of an audience, I've seen voice-over and narration work very well in films a number of times, and I think it would have been helpful had it been there for The Handmaid's Tale. After all its HER story."

Portman concludes that "In the end director Volker Schlondorff sided with Richardson"; Portman does not acknowledge Pinter's already-quoted account that he gave both Schlondorff and Atwood "carte blanche" to make whatever changes they wanted to his script because he was too "exhausted" from the experience to work further on it; in 1990, when she reportedly made her comments quoted by Portman, Richardson herself may not have known that.[3]

Filming locations

The scene where the hanging occurred was filmed in front of Duke Chapel on the campus of Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.[4]

Notes

- ^ Johnson makes this point in his article "Uphill Battle: Handmaid's Hard Times". Maclean's 26 Feb. 1990.

- ^ Cf. "Harold Pinter's Lolita: 'My Sin, My Soul'", by Christopher C. Hudgins: "During our 1994 interview, Pinter told [Steven H.] Gale and me that he had learned his lesson after the revisions imposed on his script for The Handmaid's Tale, which he has decided not to publish. When his script for Remains of the Day was radically revised by the James Ivory–Ismail Merchant partnership, he refused to allow his name to be listed in the credits" (Gale, Films 125).

- ^ Referring to Pinter's screenplay for the film of John Fowles's novel The French Lieutenant's Woman, Gale observes: "Although in other films he has used a voice-over narrator, the obvious choice for retaining the Fowles touch, Pinter is on record as not being fond of the device, and he wanted to avoid it here if possible" (Sharp Cut 239); in relation to his screenplay for Lolita, "Despite the director's wanting him to use a good bit of that narrative as voice-over in the film, Pinter insist[ed] that he would never use it in a description of action … [and, Gale describes] how he put his opinion into practice" (358). Gale discusses the use of voice-over in or relating to other screenplays by Pinter, including those that he wrote for Accident, The Comfort of Strangers (in which Richardson also stars), The Go-Between, The Last Tycoon, The Remains of the Day, and The Trial (198–99, 234, 327, 353-54, 341, 367), as well as the voice overs that he did write for his script of The Handmaid's Tale:

The novel does not include the murder of the Commander, and Kate's fate is left completely unresolved—the van waits in the driveway, "and so I step up, into the darkness within; or else the light" ([Atwood, The Handmaid's Tale (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1986)] 295). The escape to Canada and the reappearance of the child and Nick are Pinter's inventions for the movie version. As shot, there is a voice-over in which Kate explains (accompanied by light symphonic music that contrasts with that of the opening scene) that she is now safe in the mountains held by the rebels. Bolstered by occasional messages from Nick, she awaits the birth of her baby while she dreams about Jill, whom she feels she is going to find eventually. (Gale, Sharp Cut 318)

- ^ "April 18: Minutes of the Academic Council, Academic Council Archive, Duke University, 18 Apr. 1996, Web, 9 May 2009.

Works cited

Billington, Michael. Harold Pinter. London: Faber and Faber, 2007. ISBN 9780571234769 (13). Updated 2nd ed. of The Life and Work of Harold Pinter. 1996. London: Faber and Faber, 1997. ISBN 0571171036 (10). Print.

Gale, Steven H. Sharp Cut: Harold Pinter's Screenplays and the Artistic Process. Lexington, KY: The UP of Kentucky, 2003. ISBN 0813122449 (10). ISBN 9780813122441 (13). Print.

–––, ed. The Films of Harold Pinter. Albany: SUNY P, 2001. ISBN 0791449327. ISBN 9780791449325. Print. [A collection of essays; does not include an essay on The Handmaid's Tale; mentions it on 1, 2, 84n3, 125.]

Hudgins, Christopher C. "Three Unpublished Harold Pinter Filmscripts: The Handmaid's Tale, The Remains of the Day, Lolita." The Pinter Review: Nobel Prize / Europe Theatre Prize Volume: 2005–2008. Ed. Francis Gillen with Steven H. Gale. Tampa: U of Tampa P, 2008. 132–39. ISBN 9781879852198 (hardcover). ISBN 9781879852204 (softcover). ISSN 08959706. Print.

Johnson, Brian D. "Uphill Battle: Handmaid's Hard Times." Maclean's 26 Feb. 1990. Print.

Portman, Jamie (CanWest News Service). "Not the Tale of a Handmaid: Natasha Richardson Has Led an Outspoken Career". Canada.com. CanWest News Service, 18 Mar. 2009. Web. 24 Mar. 2009.

External links

- The Handmaid's Tale at IMDb

- The Handmaid's Tale at AllMovie

- The Handmaid's Tale at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Handmaid's Tale (novel) – "Context" at Spark Notes.