Phosphor: Difference between revisions

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

Many phosphors tend to lose efficiency gradually by several mechanisms. The activators can undergo change of [[valence (chemistry)|valence]] (usually [[oxidation]]), the [[crystal lattice]] degrades, atoms - often the activators - diffuse through the material, the surface undergoes chemical reactions with the environment with consequent loss of efficiency or buildup of a layer absorbing either the exciting or the radiated energy, etc. |

Many phosphors tend to lose efficiency gradually by several mechanisms. The activators can undergo change of [[valence (chemistry)|valence]] (usually [[oxidation]]), the [[crystal lattice]] degrades, atoms - often the activators - diffuse through the material, the surface undergoes chemical reactions with the environment with consequent loss of efficiency or buildup of a layer absorbing either the exciting or the radiated energy, etc. |

||

The degradation of electroluminescent devices |

The degradation of electroluminescent devices depends on frequency of driving current, the luminance level, and temperature; moisture impairs phosphor lifetime very noticeably as well. |

||

Examples: |

Examples: |

||

Revision as of 17:01, 26 January 2011

A phosphor, most generally, is a substance that exhibits the phenomenon of luminescence. Somewhat confusingly, this includes both phosphorescent materials, which show a slow decay in brightness (>1ms), and fluorescent materials, where the emission decay takes place over tens of nanoseconds. Phosphorescent materials are known for their use in radar screens and glow-in-the-dark toys, whereas fluorescent materials are common in CRT screens, sensors, and white LEDs.

Phosphors are transition metal compounds or rare earth compounds of various types. The most common uses of phosphors are in CRT displays and fluorescent lights. CRT phosphors were standardized beginning around World War II and designated by the letter "P" followed by a number.

Note: Phosphorus, the chemical element from the phenomenon draws its name from, emits light under certain conditions, but this is due to chemiluminescence, not phosphorescence.[1]

Principles

A material can emit light either through incandescence, where all atoms radiate, or by luminescence, where only a small fraction of atoms, called emission centers or luminescence centers, emit light. In inorganic phosphors, these inhomogeneities in the crystal structure are created usually by addition of a trace amount of dopants, impurities called activators. (In rare cases dislocations or other crystal defects can play the role of the impurity.) The wavelength emitted by the emission center is dependent on the atom itself, and on the surrounding crystal structure.

The scintillation process in inorganic materials is due to the electronic band structure found in the crystals. An incoming particle can excite an electron from the valence band to either the conduction band or the exciton band (located just below the conduction band and separated from the valence band by an energy gap). This leaves an associated hole behind, in the valence band. Impurities create electronic levels in the forbidden gap. The excitons are loosely bound electron-hole pairs that wander through the crystal lattice until they are captured as a whole by impurity centers. The latter then rapidly de-excite by emitting scintillation light (fast component). In case of inorganic scintillators, the activator impurities are typically chosen so that the emitted light is in the visible range or near-UV where photomultipliers are effective. The holes associated with electrons in the conduction band are independent from the latter. Those holes and electrons are captured successively by impurity centers exciting certain metastable states not accessible to the excitons. The delayed de-excitation of those metastable impurity states, slowed down by reliance on the low-probability forbidden mechanism, again results in light emission (slow component).

Phosphor degradation

Many phosphors tend to lose efficiency gradually by several mechanisms. The activators can undergo change of valence (usually oxidation), the crystal lattice degrades, atoms - often the activators - diffuse through the material, the surface undergoes chemical reactions with the environment with consequent loss of efficiency or buildup of a layer absorbing either the exciting or the radiated energy, etc.

The degradation of electroluminescent devices depends on frequency of driving current, the luminance level, and temperature; moisture impairs phosphor lifetime very noticeably as well.

Examples:

- BaMgAl10O17:Eu2+ (BAM), a plasma display phosphor, undergoes oxidation of the dopant during baking. Three mechanisms are involved; absorption of oxygen atoms into oxygen vacancies on the crystal surface, diffusion of Eu(II) along the conductive layer, and electron transfer from Eu(II) to adsorbed oxygen atoms, leading to formation of Eu(III) with corresponding loss of emissivity.[2] Thin coating of aluminium phosphate or lanthanum(III) phosphate is effective in creation a barrier layer blocking access of oxygen to the BAM phosphor, for the cost of reduction of phosphor efficiency.[3] Addition of hydrogen, acting as a reducing agent, to argon in the plasma displays significantly extends the lifetime of BAM:Eu2+ phosphor, by reducing the Eu(III) atoms back to Eu(II).[4]

- Y2O3:Eu phosphors under electron bombardment in presence of oxygen form a non-phosphorescent layer on the surface, where electron-hole pairs recombine nonradiatively via surface states.[5]

- ZnS:Mn, used in AC thin film electroluminescent (ACTFEL) devices degrades mainly due to formation of deep electron traps, by reaction of water molecules with the dopant; the traps act as centers for nonradiative recombination. The traps also damage the crystal lattice. Phosphor aging leads to decreased brightness and elevated threshold voltage.[6]

- ZnS-based phosphors in CRTs and FEDs degrade by surface excitation, coulombic damage, build-up of electric charge, and thermal quenching. Electron-stimulated reactions of the surface are directly correlated to loss of brightness. The electrons dissociate impurities in the environment, the reactive oxygen species then attack the surface and form carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide with traces of carbon, and nonradiative zinc oxide and zinc sulfate on the surface; the reactive hydrogen removes sulfur from the surface as hydrogen sulfide, forming nonradiative layer of metallic zinc. Sulfur can be also removed as sulfur oxides.[7]

- ZnS and CdS phosphors degrade by reduction of the metal ions by captured electrons. The Me2+ ions are reduced to Me+; two Me+ then exchange an electron and become one Me2+ and one neutral Me atom. The reduced metal can be observed as a visible darkening of the phosphor layer. The darkening (and the brightness loss) is proportional to the phosphor's exposition to electrons, and can be observed on some CRT screens that displayed the same image (e.g. a terminal login screen) for prolonged periods.[8]

Materials

Phosphors are usually made from a suitable host material with an added activator. The best known type is a copper-activated zinc sulfide and the silver-activated zinc sulfide (zinc sulfide silver).

The host materials are typically oxides, nitrides and oxynitrides[9], sulfides, selenides, halides or silicates of zinc, cadmium, manganese, aluminium, silicon, or various rare earth metals. The activators prolong the emission time (afterglow). In turn, other materials (such as nickel) can be used to quench the afterglow and shorten the decay part of the phosphor emission characteristics.

Many phosphor powders are produced in low-temperature processes, such as sol-gel and usually require post-annealing at temperatures of ~1000 °C, which is undesirable for many applications. However, proper optimization of the growth process allows to avoid the annealing.[10]

Phosphors used for fluorescent lamps require a multi-step production process, with details that vary depending on the particular phosphor. Bulk material must be milled to obtain a desired particle size range, since large particles produce a poor quality lamp coating and small particles produce less light and degrade more quickly. During the firing of the phosphor, process conditions must be controlled to prevent oxidation of the phosphor activators or contamination from the process vessels. After milling the phosphor may be washed to remove minor excess of activator elements. Volatile elements must not be allowed to escape during processing. Lamp manufacturers have changed composition of phosphors to eliminate some toxic elements, such as beryllium, cadmium, or thallium, formerly used. [11]

The commonly quoted parameters for phosphors are the wavelength of emission maximum (in nanometers, or alternatively color temperature in kelvins for white blends), the peak width (in nanometers at 50% of intensity), and decay time (in seconds).

Applications

Lighting

Phosphor layers provide most of the light produced by fluorescent lamps, and are also used to improve the balance of light produced by metal halide lamps. Various neon signs use phosphor layers to produce different colors of light. Electroluminescent displays found, for example, in aircraft instrument panels, use a phosphor layer to produce glare-free illumination or as numeric and graphic display devices.

Phosphor thermometry

Phosphor thermometry is a temperature measurement approach that utilizes the temperature dependence of certain phosphors for this purpose. For this, a phosphor coating is applied to a surface of interest and, usually, the decay time is the emission parameter that indicates temperature. Because the illumination and detection optics can be situated remotely, the method may be used for moving surfaces such as high speed motor surfaces. Also, phosphor may be applied to the end of an optical fiber as an optical analog of a thermocouple.

While the previously mentioned method is focusing on the temperature detection, the inclusion of phosphorescent materials into a ceramic component, for example a Thermal barrier coating, can yield a micro probe to detect the aging mechanisms or changes to other physical parameters that affect the local atomic surroundings of the optical active ion.[12][13][14]. The latter proved the viability of detecting hot corrosion processes in Yttria-stabilized zirconia.

Glow-in-the-dark toys

- Calcium sulfide with strontium sulfide with bismuth as activator, (Ca,Sr)S:Bi, yields blue light with glow times up to 12 hours, red and orange are modifications of the zinc sulfide formula. Red color can be obtained from strontium sulfide.

- Zinc sulfide with about 5 ppm of a copper activator is the most common phosphor for the glow-in-the-dark toys and items. It is also called GS phosphor.

- Mix of zinc sulfide and cadmium sulfide emit color depending on their ratio; increasing of the CdS content shifts the output color towards longer wavelengths; its persistence ranges between 1–10 hours.

- Strontium aluminate activated by europium, SrAl2O4:Eu(II):Dy(III), is a newer material with higher brightness and significantly longer glow persistence; it produces green and aqua hues, where green gives the highest brightness and aqua the longest glow time. SrAl2O4:Eu:Dy is about 10 times brighter, 10 times longer glowing, and 10 times more expensive than ZnS:Cu. The excitation wavelengths for strontium aluminate range from 200 to 450 nm. The wavelength for its green formulation is 520 nm, its blue-green version emits at 505 nm, and the blue one emits at 490 nm. Colors with longer wavelengths can be obtained from the strontium aluminate as well, though for the price of some loss of brightness.

In these applications, the phosphor is directly added to the plastic used to mold the toys, or mixed with a binder for use as paints.

ZnS:Cu phosphor is used in glow-in-the-dark cosmetic creams frequently used for Halloween make-ups. Generally, the persistence of the phosphor increases as the wavelength increases. See also lightstick for chemiluminescence-based glowing items.

Radioluminescence

Zinc sulfide phosphors are used with radioactive materials, where the phosphor was excited by the alpha- and beta-decaying isotopes, to create luminescent paint for dials of watches and instruments (radium dials). Between 1913 and 1950 a radium-228 and radium-226 were used to activate a phosphor made of silver doped zinc sulfide (ZnS:Ag), which gave a greenish glow. The phosphor is not suitable to be used in layers thicker than 25 mg/cm², as the self-absorption of the light then becomes a problem. Furthermore, zinc sulfide undergoes degradation of its crystal lattice structure, leading to gradual loss of brightness significantly faster than the depletion of radium. ZnS:Ag coated spinthariscope screens were used by Ernest Rutherford in his experiments discovering atomic nucleus.

Copper doped zinc sulfide (ZnS:Cu) is the most common phosphor used and yields blue-green light. Copper and magnesium doped zinc sulfide (ZnS:Cu,Mg) yields yellow-orange light.

Tritium is also used as a source of radiation in various products utilizing tritium illumination.

Electroluminescence

Electroluminescence can be exploited in light sources. Such sources typically emit from a large area, which makes them suitable for backlights of eg. LCD displays. The excitation of the phosphor is usually achieved by application of high-intensity electric field, usually with suitable frequency. Current electroluminescent light sources tend to degrade with use, resulting in their relatively short operation lifetimes.

ZnS:Cu was the first formulation successfully displaying electroluminescence, tested at 1936 by Georges Destriau in Madame Marie Curie laboratories in Paris.

Indium tin oxide (ITO, also known under trade name IndiGlo) composite is used in some Timex watches, though as the electrode material, not as a phosphor itself. "Lighttape" is another trade name of an electroluminescent material, used in electroluminescent light strips.

White LEDs

White light-emitting diodes are usually blue InGaN LEDs with a coating of a suitable material. Cerium(III)-doped YAG (YAG:Ce3+, or Y3Al5O12:Ce3+) is often used; it absorbs the light from the blue LED and emits in a broad range from greenish to reddish, with most of output in yellow. The pale yellow emission of the Ce3+:YAG can be tuned by substituting the cerium with other rare earth elements such as terbium and gadolinium and can even be further adjusted by substituting some or all of the aluminium in the YAG with gallium. However, this process is not one of phosphorescence. The yellow light is produced by a process known as scintillation, the complete absence of an afterglow being one of the characteristics of the process.

Some rare-earth doped Sialons are photoluminescent and can serve as phosphors. Europium(II)-doped β-SiAlON absorbs in ultraviolet and visible light spectrum and emits intense broadband visible emission. Its luminance and color does not change significantly with temperature, due to the temperature-stable crystal structure. It has a great potential as a green down-conversion phosphor for white LEDs; a yellow variant also exists. For white LEDs, a blue LED is used with a yellow phosphor, or with a green and yellow SiAlON phosphor and a red CaAlSiN3-based (CASN) phosphor.[15][16][17]

White LEDs can also be made by coating near ultraviolet (NUV) emitting LEDs with a mixture of high efficiency europium based red and blue emitting phosphors plus green emitting copper and aluminium doped zinc sulfide (ZnS:Cu,Al). This is a method analogous to the way fluorescent lamps work.

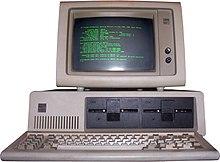

Cathode ray tubes

Cathode ray tubes produce signal-generated light patterns in a (typically) round or rectangular format. Bulky CRTs were used in the black-and-white household television ("TV") sets that became popular in the 1950s, as well as first-generation, tube-based color TVs, and most earlier computer monitors. CRTs have also been widely used in scientific and engineering instrumentation, such as oscilloscopes, usually with a single phosphor color, typically green.

White (in black-and-white): The mix of zinc cadmium sulfide and zinc sulfide silver, the ZnS:Ag+(Zn,Cd)S:Ag is the white P4 phosphor used in black and white television CRTs.

Red: Yttrium oxide-sulfide activated with europium is used as the red phosphor in color CRTs. The development of color TVs took a long time due to the long search for a red phosphor. The first red emitting rare earth phosphor, YVO4,Eu3, was introduced by Levine and Palilla as a primary color in television in 1964.[18] In single crystal form, it was used as an excellent polarizer and laser material.[19]

Yellow: When mixed with cadmium sulfide, the resulting zinc cadmium sulfide (Zn,Cd)S:Ag, provides strong yellow light.

Green: Combination of zinc sulfide with copper, the P31 phosphor or ZnS:Cu, provides green light peaking at 531 nm, with long glow.

Blue: Combination of zinc sulfide with few ppm of silver, the ZnS:Ag, when excited by electrons, provides strong blue glow with maximum at 450 nm, with short afterglow with 200 nanosecond duration. It is known as the P22B phosphor. This material, zinc sulfide silver, is still one of the most efficient phosphors in cathode ray tubes. It is used as a blue phosphor in color CRTs.

The phosphors are usually poor electrical conductors. This may lead to deposition of residual charge on the screen, effectively decreasing the energy of the impacting electrons due to electrostatic repulsion (an effect known as "sticking"). To eliminate this, a thin layer of aluminium is deposited over the phosphors and connected to the conductive layer inside the tube. This layer also reflects the phosphor light to the desired direction, and protects the phosphor from ion bombardment resulting from an imperfect vacuum.

Standard phosphor types

| Phosphor | Composition | Color | Wavelength | Peak width | Persistence | Usage | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1, GJ | Zn2SiO4:Mn (Willemite) | Green | 528 nm | 40 nm[21] | 1-100ms | CRT, Lamp | Oscilloscopes |

| P4 | ZnS:Ag+(Zn,Cd)S:Ag | White | - | - | Short | CRT | Black and white TV CRTs and display tubes. |

| P4 (Cd-free) | ZnS:Ag+ZnS:Cu+Y2O2S:Eu | White | - | - | Short | CRT | Black and white TV CRTs and display tubes, Cd free. |

| P4, GE | ZnO:Zn | Green | 505 nm | - | 1-10µs | VFD | VFDs |

| P7 | ? | Blue with Yellow persistance | - | - | Long | CRT | Radar PPI, old EKG monitors |

| P10 | KCl | green-absorbing scotophor | - | - | Long | Dark-trace CRTs | Radar screens; turns from translucent white to dark magenta, stays changed until erased by heating or infrared light |

| P11, BE | ZnS:Ag,Cl or ZnS:Zn | Blue | 460 nm | - | 0.01-1 ms | CRT, VFD | Display tubes and VFDs |

| P19, LF | (KF,MgF2):Mn | Orange-Yellow | 590 nm | - | Long | CRT | Radar screens |

| P20, KA | (Zn,Cd)S:Ag or (Zn,Cd)S:Cu | Yellow-green | - | - | 1-100 ms | CRT | Display tubes |

| P22R | Y2O2S:Eu+Fe2O3 | Red | - | - | Short | CRT | Red phosphor for TV screens |

| P22G | ZnS:Cu,Al | Green | - | - | Short | CRT | Green phosphor for TV screens |

| P22B | ZnS:Ag+Co-on-Al2O3 | Blue | - | - | Short | CRT | Blue phosphor for TV screens |

| P26, LC | (KF,MgF2):Mn | Orange | 595 nm | - | Long | CRT | Radar screens |

| P28, KE | (Zn,Cd)S:Cu,Cl | Yellow | - | - | - | CRT | Display tubes |

| P31, GH | ZnS:Cu or ZnS:Cu,Ag | Yellowish-green | - | - | 0.01-1 ms | CRT | Oscilloscopes |

| P33, LD | MgF2:Mn | Orange | 590 nm | - | > 1sec | CRT | Radar screens |

| P38, LK | (Zn,Mg)F2:Mn | Orange-Yellow | 590 nm | - | Long | CRT | Radar screens |

| P39, GR | Zn2SiO4:Mn,As | Green | 525 nm | - | - | CRT | Display tubes |

| P40, GA | ZnS:Ag+(Zn,Cd)S:Cu | White | - | - | - | CRT | Display tubes |

| P43, GY | Gd2O2S:Tb | Yellow-green | 545 nm | - | - | CRT | Display tubes |

| P45, WB | Y2O2S:Tb | White | 545 nm | - | Short | CRT | Viewfinders |

| P46, KG | Y3Al5O12:Ce | Green | 530 nm | - | - | CRT | Beam-index tube |

| P47, BH | Y2SiO5:Ce | Blue | 400 nm | - | - | CRT | Beam-index tube |

| P53, KJ | Y3Al5O12:Tb | Yellow-green | 544 nm | - | Short | CRT | Projection tubes |

| P55, BM | ZnS:Ag,Al | Blue | 450 nm | - | Short | CRT | Projection tubes |

| ? | ZnS:Ag | Blue | 450 nm | - | - | CRT | - |

| ? | ZnS:Cu,Al or ZnS:Cu,Au,Al | Green | 530 nm | - | - | CRT | - |

| ? | (Zn,Cd)S:Cu,Cl+(Zn,Cd)S:Ag,Cl | White | - | - | - | CRT | - |

| ? | Y2SiO5:Tb | Green | 545 nm | - | - | CRT | Projection tubes |

| ? | Y2OS:Tb | Green | 545 nm | - | - | CRT | Display tubes |

| ? | Y3(Al,Ga)5O12:Ce | Green | 520 nm | - | Short | CRT | Beam-index tube |

| ? | Y3(Al,Ga)5O12:Tb | Yellow-green | 544 nm | - | Short | CRT | Projection tubes |

| ? | InBO3:Tb | Yellow-green | 550 nm | - | - | CRT | - |

| ? | InBO3:Eu | Yellow | 588 nm | - | - | CRT | - |

| ? | InBO3:Tb+InBO3:Eu | amber | - | - | - | CRT | Computer displays |

| ? | InBO3:Tb+InBO3:Eu+ZnS:Ag | White | - | - | - | CRT | - |

| ? | (Ba,Eu)Mg2Al16O27 | Blue | - | - | - | Lamp | Trichromatic fluorescent lamps |

| ? | (Ce,Tb)MgAl11O19 | Green | 546 nm | 9 nm | - | Lamp | Trichromatic fluorescent lamps[21] |

| BAM | BaMgAl10O17:Eu,Mn | Blue | 450 nm | - | - | Lamp, displays | Trichromatic fluorescent lamps |

| ? | BaMg2Al16O27:Eu(II) | Blue | 450 nm | 52 nm | - | Lamp | Trichromatic fluorescent lamps[21] |

| BAM | BaMgAl10O17:Eu,Mn | Blue-Green | 456 nm,514 nm | - | - | Lamp | - |

| ? | BaMg2Al16O27:Eu(II),Mn(II) | Blue-Green | 456 nm, 514 nm | 50 nm 50%[21] | - | Lamp | |

| ? | Ce0.67Tb0.33MgAl11O19:Ce,Tb | Green | 543 nm | - | - | Lamp | Trichromatic fluorescent lamps |

| ? | Zn2SiO4:Mn,Sb2O3 | Green | 528 nm | - | - | Lamp | - |

| ? | CaSiO3:Pb,Mn | Orange-Pink | 615 nm | 83 nm[21] | - | Lamp | |

| ? | CaWO4 (Scheelite) | Blue | 417 nm | - | - | Lamp | - |

| ? | CaWO4:Pb | Blue | 433 nm/466 nm | 111 nm | - | Lamp | Wide bandwidth[21] |

| ? | MgWO4 | Blue pale | 473 nm | 118 nm | - | Lamp | Wide bandwidth, deluxe blend component [21] |

| ? | (Sr,Eu,Ba,Ca)5(PO4)3Cl | Blue | - | - | - | Lamp | Trichromatic fluorescent lamps |

| ? | Sr5Cl(PO4)3:Eu(II) | Blue | 447 nm | 32 nm[21] | - | Lamp | - |

| ? | (Ca,Sr,Ba)3(PO4)2Cl2:Eu | Blue | 452 nm | - | - | Lamp | - |

| ? | (Sr,Ca,Ba)10(PO4)6Cl2:Eu | Blue | 453 nm | - | - | Lamp | Trichromatic fluorescent lamps |

| ? | Sr2P2O7:Sn(II) | Blue | 460 nm | 98 nm | - | Lamp | Wide bandwidth, deluxe blend component[21] |

| ? | Sr6P5BO20:Eu | Blue-Green | 480 nm | 82 nm[21] | - | Lamp | - |

| ? | Ca5F(PO4)3:Sb | Blue | 482 nm | 117 nm | - | Lamp | Wide bandwidth[21] |

| ? | (Ba,Ti)2P2O7:Ti | Blue-Green | 494 nm | 143 nm | - | Lamp | Wide bandwidth, deluxe blend component [21] |

| ? | 3Sr3(PO4)2.SrF2:Sb,Mn | Blue | 502 nm | - | - | Lamp | - |

| ? | Sr5F(PO4)3:Sb,Mn | Blue-Green | 509 nm | 127 nm | - | Lamp | Wide bandwidth[21] |

| ? | Sr5F(PO4)3:Sb,Mn | Blue-Green | 509 nm | 127 nm | - | Lamp | Wide bandwidth[21] |

| ? | LaPO4:Ce,Tb | Green | 544 nm | - | - | Lamp | Trichromatic fluorescent lamps |

| ? | (La,Ce,Tb)PO4 | Green | - | - | - | Lamp | Trichromatic fluorescent lamps |

| ? | (La,Ce,Tb)PO4:Ce,Tb | Green | 546 nm | 6 nm | - | Lamp | Trichromatic fluorescent lamps[21] |

| ? | Ca3(PO4)2.CaF2:Ce,Mn | Yellow | 568 nm | - | - | Lamp | - |

| ? | (Ca,Zn,Mg)3(PO4)2:Sn | Orange-Pink | 610 nm | 146 nm | - | Lamp | Wide bandwidth, blend component[21] |

| ? | (Zn,Sr)3(PO4)2:Mn | Orange-Red | 625 nm | - | - | Lamp | - |

| ? | (Sr,Mg)3(PO4)2:Sn | Orange-Pinkish White | 626 nm | 120 nm | - | Fluorescent Lamps | Wide bandwidth, deluxe blend component[21] |

| ? | (Sr,Mg)3(PO4)2:Sn(II) | Orange-Red | 630 nm | - | - | Fluorescent Lamps | - |

| ? | Ca5F(PO4)3:Sb,Mn | 3800K | - | - | - | Fluorescent Lamps | Lite-white blend[21] |

| ? | Ca5(F,Cl)(PO4)3:Sb,Mn | White-Cold/Warm | - | - | - | Fluorescent Lamps | 2600K to 9900K, for very high output lamps[21] |

| ? | (Y,Eu)2O3 | Red | - | - | - | Lamp | Trichromatic fluorescent lamps |

| ? | Y2O3:Eu(III) | Red | 611 nm | 4 nm | - | Lamp | Trichromatic fluorescent lamps[21] |

| ? | Mg4(F)GeO6:Mn | Red | 658 nm | 17 nm | - | High Pressure Mercury Lamps | [21] |

| ? | Mg4(F)(Ge,Sn)O6:Mn | Red | 658 nm | - | - | Lamp | - |

| ? | Y(P,V)O4:Eu | Orange-Red | 619 nm | - | - | Lamp | - |

| ? | YVO4:Eu | Orange-Red | 619 nm | - | - | High Pressure Mercury and Metal Halide Lamps | - |

| ? | Y2O2S:Eu | Red | 626 nm | - | - | Lamp | - |

| ? | 3.5 MgO · 0.5 MgF2 · GeO2 :Mn | Red | 655 nm | - | - | Lamp | 3.5 MgO · 0.5 MgF2 · GeO2 :Mn |

| ? | Mg5As2O11:Mn | Red | 660 nm | - | - | High Pressure Mercury Lamps, 1960s | - |

| ? | SrAl2O7:Pb | Ultraviolet | 313 nm | - | - | Special Fluorescent Lamps for Medical use | Ultraviolet |

| CAM | LaMgAl11O19:Ce | Ultraviolet | 340 nm | 52 nm | - | Black-light Fluorescent Lamps | Ultraviolet |

| LAP | LaPO4:Ce | Ultraviolet | 320 nm | 38 nm | - | Medical and scientific U.V. Lamps | Ultraviolet |

| SAC | SrAl12O19:Ce | Ultraviolet | 295 nm | 34 nm | - | Lamp | Ultraviolet |

| BSP | BaSi2O5:Pb | Ultraviolet | 350 nm | 40 nm | - | Lamp | Ultraviolet |

| ? | SrFB2O3:Eu(II) | Ultraviolet | 366 nm | - | - | Lamp | Ultraviolet |

| SBE | SrB4O7:Eu | Ultraviolet | 368 nm | 15 nm | - | Lamp | Ultraviolet |

| SMS | Sr2MgSi2O7:Pb | Ultraviolet | 365 nm | 68 nm | - | Lamp | Ultraviolet |

| ? | MgGa2O4:Mn(II) | Blue-Green | - | - | - | Lamp | Black light displays |

Various

Some other phosphors commercially available, for use as X-ray screens, neutron detectors, alpha particle scintillators, etc, are:

- Gd2O2S:Tb (P43), green (peak at 545 nm), 1.5 ms decay to 10%, low afterglow, high X-ray absorption, for X-ray, neutrons and gamma

- Gd2O2S:Eu, red (627 nm), 850 µs decay, afterglow, high X-ray absorption, for X-ray, neutrons and gamma

- Gd2O2S:Pr, green (513 nm), 7 µs decay, no afterglow, high X-ray absorption, for X-ray, neutrons and gamma

- Gd2O2S:Pr,Ce,F, green (513 nm), 4 µs decay, no afterglow, high X-ray absorption, for X-ray, neutrons and gamma

- Y2O2S:Tb (P45), white (545 nm), 1.5 ms decay, low afterglow, for low-energy X-ray

- Y2O2S:Eu (P22R), red (627 nm), 850 µs decay, afterglow, for low-energy X-ray

- Y2O2S:Pr, white (513 nm), 7 µs decay, no afterglow, for low-energy X-ray

- Zn(0.5)Cd(0.4)S:Ag (HS), green (560 nm), 80 µs decay, afterglow, efficient but low-res X-ray

- Zn(0.4)Cd(0.6)S:Ag (HSr), red (630 nm), 80 µs decay, afterglow, efficient but low-res X-ray

- CdWO4, blue (475 nm), 28 µs decay, no afterglow, intensifying phosphor for X-ray and gamma

- CaWO4, blue (410 nm), 20 µs decay, no afterglow, intensifying phosphor for X-ray

- MgWO4, white (500 nm), 80 µs decay, no afterglow, intensifying phosphor

- Y2SiO5:Ce (P47), blue (400 nm), 120 ns decay, no afterglow, for electrons, suitable for photomultipliers

- YAlO3:Ce (YAP), blue (370 nm), 25 ns decay, no afterglow, for electrons, suitable for photomultipliers

- Y3Al5O12:Ce (YAG), green (550 nm), 70 ns decay, no afterglow, for electrons, suitable for photomultipliers

- Y3(Al,Ga)5O12:Ce (YGG), green (530 nm), 250 ns decay, low afterglow, for electrons, suitable for photomultipliers

- CdS:In, green (525 nm), <1 ns decay, no afterglow, ultrafast, for electrons

- ZnO:Ga, blue (390 nm), <5 ns decay, no afterglow, ultrafast, for electrons

- ZnO:Zn (P15), blue (495 nm), 8 µs decay, no afterglow, for low-energy electrons

- (Zn,Cd)S:Cu,Al (P22G), green (565 nm), 35 µs decay, low afterglow, for electrons

- ZnS:Cu,Al,Au (P22G), green (540 nm), 35 µs decay, low afterglow, for electrons

- ZnCdS:Ag,Cu (P20), green (530 nm), 80 µs decay, low afterglow, for electrons

- ZnS:Ag (P11), blue (455 nm), 80 µs decay, low afterglow, for alpha particles and electrons

- anthracene, blue (447 nm), 32 ns decay, no afterglow, for alpha particles and electrons

- plastic (EJ-212), blue (400 nm), 2.4 ns decay, no afterglow, for alpha particles and electrons

- Zn2SiO4:Mn (P1), green (530 nm), 11 ms decay, low afterglow, for electrons

- ZnS:Cu (GS), green (520 nm), decay in minutes, long afterglow, for X-rays

- NaI:Tl, for X-ray, alpha, and electrons

- CsI:Tl, green (545 nm), 5 µs decay, afterglow, for X-ray, alpha, and electrons

- 6LiF/ZnS:Ag (ND), blue (455 nm), 80 µs decay, for thermal neutrons

- 6LiF/ZnS:Cu,Al,Au (NDg), green (565 nm), 35 µs decay, for neutrons

See also

References

- ^ Emsley, John (2000). The Shocking History of Phosphorus. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0330390058.

- ^ Bizarri, G; Moine, B (2005). "On phosphor degradation mechanism: thermal treatment effects". Journal of Luminescence. 113: 199. doi:10.1016/j.jlumin.2004.09.119.

- ^ Lakshmanan, p.171

- ^ Tanno, Hiroaki; Fukasawa, Takayuki; Zhang, Shuxiu; Shinoda, Tsutae; Kajiyama, Hiroshi (2009). "Lifetime Improvement of BaMgAl10O17:Eu2+Phosphor by Hydrogen Plasma Treatment". Japanese Journal of Applied Physics. 48: 092303. doi:10.1143/JJAP.48.092303.

- ^ Ntwaeaborwa, O. M.; Hillie, K. T.; Swart, H. C. (2004). "Degradation of Y2O3:Eu phosphor powders". Physica status solidi (c). 1: 2366. doi:10.1002/pssc.200404813.

- ^ Wang, Ching-Wu; Sheu, Tong-Ji; Su, Yan-Kuin; Yokoyama, Meiso (1997). "Deep Traps and Mechanism of Brightness Degradation in Mn-doped ZnS Thin-Film Electroluminescent Devices Grown by Metal-Organic Chemical Vapor Deposition". Japanese Journal of Applied Physics. 36: 2728. doi:10.1143/JJAP.36.2728.

- ^ Lakshmanan, pp. 51, 76

- ^ http://tubedevices.com/alek/pwl/luminofory/luminofory.ppt

- ^ Xie, Rong-Jun; Hirosaki, Naoto (2007). "Silicon-based oxynitride and nitride phosphors for white LEDs—A review" (free pdf). Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 8: 588. doi:10.1016/j.stam.2007.08.005.

- ^ Li, Hui-Li; Hirosaki, Naoto; Xie, Rong-Jun; Suehiro, Takayuki; Mitomo, Mamoru (2007). "Fine yellow α-SiAlON:Eu phosphors for white LEDs prepared by the gas-reduction–nitridation method" (free pdf). Sci. Techno. Adv. Mater. 8: 601. doi:10.1016/j.stam.2007.09.003.

- ^ Raymond Kane, Heinz Sell Revolution in lamps: a chronicle of 50 years of progress (2nd ed.), The Fairmont Press, Inc. 2001 ISBN 0-88173-378-4 . Chapter 5 extensively discusses history, application and manufacturing of phosphors for lamps.

- ^ K-L. Choy, A. L. Heyes and J. Feist (1998) "Thermal barrier coating with thermoluminescent indicator material embedded therein" U.S. patent 6,974,641

- ^ A. M. Srivastava, A. A. Setlur, H. A. Comanzo, J. W. Devitt, J. A. Ruud and L. N. Brewer (2001) "Apparatus for determining past-service conditions and remaining life of thermal barrier coatings and components having such coatings" U.S. patent 6730918B2

- ^ J. P. Feist and A. L. Heyes (2003) "Coatings and an optical method for detecting corrosion process in coatings" GB. Patent 0318929.7

- ^ Youn-Gon Park; et al. "Luminescence and temperature dependency of β-SiAlON phosphor". Samsung Electro Mechanics Co.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Hideyoshi Kume, Nikkei Electronics (Sept 15, 2009). "Sharp to Employ White LED Using Sialon".

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Hirosaki Naoto; et al. (2005). "New sialon phosphors and white LEDs". Oyo Butsuri. 74 (11): 1449.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Levine, Albert K.; Palilla, Frank C. (1964). "A new, highly efficient red-emitting cathodoluminescent phosphor (YVO4:Eu) for color television". Applied Physics Letters. 5: 118. doi:10.1063/1.1723611.

- ^ Fields, R. A.; Birnbaum, M.; Fincher, C. L. (1987). "Highly efficient Nd:YVO4 diode-laser end-pumped laser". Applied Physics Letters. 51: 1885. doi:10.1063/1.98500.

- ^ Shigeo Shionoya (1999). "VI: Phosphors for cathode ray tubes". Phosphor handbook. Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press. ISBN 0849375606.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Osram Sylvania fluorescent lamps". Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- Arunachalam Lakshmanan (2008). Luminescence and Display Phosphors: Phenomena and Applications. Nova Publishers. ISBN 1604560185.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|isbn-status=ignored (help)

External links

- a history of electroluminescent displays.

- Fluorescence, Phosphorescence

- CRT Phosphor Characteristics (P numbers)

- Composition of CRT phosphors

- Safe Phosphors

- Silicon-based oxynitride and nitride phosphors for white LEDs—A review

- [1] & [2] - RCA Manual, Fluorescent screens (P1 to P24)