Fukushima nuclear accident: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Mgiganteus1 (talk | contribs) →Reactor unit 1: no consensus for use of "visualization" in place of real photographs |

||

| Line 174: | Line 174: | ||

===Explosion of reactor 1 building=== |

===Explosion of reactor 1 building=== |

||

At 15:36 JST on 12 March there was an explosion at unit 1. Four workers were injured, and the upper shell of the reactor building was blown away leaving in place its steel frame.<ref>{{cite web | title=福島第1原発で爆発と白煙 4人ケガ | url=http://www.news24.jp/articles/2011/03/12/06178055.html | publisher=Nippon Television Network Corporation | accessdate=12 March 2011|language=Japanese}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.tepco.co.jp/en/press/corp-com/release/11031234-e.html|title=TEPCO press release 34|publisher=Tepco|date=12 March 2011}}</ref> The outer building is designed to provide ordinary weather protection for the areas inside, not to withstand the high pressure of an explosion or to act as containment for the reactor. In the Fukushima I reactors the primary containment consists of "drywell" and "wetwell" concrete structures immediately surrounding the reactor pressure vessel.<ref name=WNN1/><ref>{{cite web|url=http://allthingsnuclear.org/post/3824043948/update-on-fukushima-reactor|publisher=allthingsnuclear.org|title=Drawing of the reactor and explanation of the containments|accessdate=13 March 2011}}</ref> |

At 15:36 JST on 12 March there was an explosion at unit 1. Four workers were injured, and the upper shell of the reactor building was blown away leaving in place its steel frame.<ref>{{cite web | title=福島第1原発で爆発と白煙 4人ケガ | url=http://www.news24.jp/articles/2011/03/12/06178055.html | publisher=Nippon Television Network Corporation | accessdate=12 March 2011|language=Japanese}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.tepco.co.jp/en/press/corp-com/release/11031234-e.html|title=TEPCO press release 34|publisher=Tepco|date=12 March 2011}}</ref> The outer building is designed to provide ordinary weather protection for the areas inside, not to withstand the high pressure of an explosion or to act as containment for the reactor. In the Fukushima I reactors the primary containment consists of "drywell" and "wetwell" concrete structures immediately surrounding the reactor pressure vessel.<ref name=WNN1/><ref>{{cite web|url=http://allthingsnuclear.org/post/3824043948/update-on-fukushima-reactor|publisher=allthingsnuclear.org|title=Drawing of the reactor and explanation of the containments|accessdate=13 March 2011}}</ref> |

||

[[File: |

[[File:2011-03-12 1800 NHK Sōgō channel news program screen shot.jpg|thumb|Before and after damage to Fukushima power plant, Unit 1]] |

||

Experts soon agreed the cause was a hydrogen explosion.<ref name=ReutersSeaWater/><ref name=reuters-20110312-10:37>{{Cite news |url=http://af.reuters.com/article/energyOilNews/idAFLDE72B05X20110312|title=Hydrogen may have caused Japan atom blast-industry|author=Fredrik Dahl, Louise Ireland|publisher=Reuters |date=12 March 2011 |accessdate=12 March 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://e.nikkei.com/e/fr/tnks/Nni20110312D12JFF03.htm |title=2011/03/13 01:04 – Meltdown caused nuke plant explosion: Safety body |publisher=E.nikkei.com |date= |accessdate=13 March 2011}}</ref> Almost certainly the hydrogen was formed inside the reactor vessel<ref name=ReutersSeaWater>{{cite web|url=http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/03/12/japan-quake-reactor-idUSTKZ00680620110312?feedType=RSS&feedName=hotStocksNews&rpc=43|title=Japan to fill leaking nuke reactor with sea water|date=12 March 2011|publisher=Reuters}}</ref> because of falling water levels, and this hydrogen then leaked into the containment building.<ref name=ReutersSeaWater/> Exposed [[Zircaloy|zircaloy]] cladded fuel rods became very hot and reacted with steam, oxidising the alloy, and [[Zirconium alloy#Oxidation of zirconium by steam|releasing hydrogen]].<ref>{{Cite book|title=Nuclear Fuel Behaviour in Loss-of-coolant Accident (LOCA) Conditions|year=2009|publisher=Nuclear Energy Agency, OECD|isbn=978-92-64-99091-3|page=140|url=https://www.oecd-nea.org/nsd/reports/2009/nea6846_LOCA.pdf}}</ref> Safety devices normally burn the generated hydrogen when it is vented before explosive concentrations are reached but these systems failed, possibly due to the shortage of electrical power. |

Experts soon agreed the cause was a hydrogen explosion.<ref name=ReutersSeaWater/><ref name=reuters-20110312-10:37>{{Cite news |url=http://af.reuters.com/article/energyOilNews/idAFLDE72B05X20110312|title=Hydrogen may have caused Japan atom blast-industry|author=Fredrik Dahl, Louise Ireland|publisher=Reuters |date=12 March 2011 |accessdate=12 March 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://e.nikkei.com/e/fr/tnks/Nni20110312D12JFF03.htm |title=2011/03/13 01:04 – Meltdown caused nuke plant explosion: Safety body |publisher=E.nikkei.com |date= |accessdate=13 March 2011}}</ref> Almost certainly the hydrogen was formed inside the reactor vessel<ref name=ReutersSeaWater>{{cite web|url=http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/03/12/japan-quake-reactor-idUSTKZ00680620110312?feedType=RSS&feedName=hotStocksNews&rpc=43|title=Japan to fill leaking nuke reactor with sea water|date=12 March 2011|publisher=Reuters}}</ref> because of falling water levels, and this hydrogen then leaked into the containment building.<ref name=ReutersSeaWater/> Exposed [[Zircaloy|zircaloy]] cladded fuel rods became very hot and reacted with steam, oxidising the alloy, and [[Zirconium alloy#Oxidation of zirconium by steam|releasing hydrogen]].<ref>{{Cite book|title=Nuclear Fuel Behaviour in Loss-of-coolant Accident (LOCA) Conditions|year=2009|publisher=Nuclear Energy Agency, OECD|isbn=978-92-64-99091-3|page=140|url=https://www.oecd-nea.org/nsd/reports/2009/nea6846_LOCA.pdf}}</ref> Safety devices normally burn the generated hydrogen when it is vented before explosive concentrations are reached but these systems failed, possibly due to the shortage of electrical power. |

||

Revision as of 00:53, 3 April 2011

This article documents a current event. Information may change rapidly as the event progresses, and initial news reports may be unreliable. The latest updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. (March 2011) |

| File:Fukushima I by Digital Globe 2.jpg Satellite image on 16 March of the four damaged reactor buildings | |

| Date | 11 March 2011 – ongoing |

|---|---|

| Time | 14:46 JST (05:46 UTC) |

| Location | Ōkuma, Fukushima, Japan |

| Coordinates | 37°25′17″N 141°1′57″E / 37.42139°N 141.03250°E |

| Outcome | INES Level 5 (Units 1, 2, and 3) and Level 3 (Unit 4) (ratings by Japanese authorities as of 18 March)[1] |

| Non-fatal injuries | 37 with physical injuries,[2] 3 workers taken to hospital for radiation exposure |

The Fukushima I nuclear accidents (福島第一原子力発電所事故, Fukushima Dai-ichi () genshiryoku hatsudensho jiko) are a series of ongoing equipment failures and releases of radioactive materials at the Fukushima I Nuclear Power Plant, following the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami at 14:46 JST on 11 March 2011. The plant comprises six separate boiling water reactors maintained by the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO). Reactors 4, 5 and 6 had been shut down prior to the earthquake for planned maintenance.[3] The remaining reactors were shut down automatically after the earthquake, but the subsequent 14-metre (46 ft) tsunami[4] flooded the plant, knocking out emergency generators needed to run pumps which cool and control the reactors. The flooding and earthquake damage prevented assistance being brought from elsewhere.

Evidence arose of partial core meltdown in reactors 1, 2, and 3; hydrogen explosions destroyed the upper cladding of the buildings housing reactors 1, 3, and 4; an explosion damaged the containment inside reactor 2; and multiple fires broke out at reactor 4. In addition, spent fuel rods stored in spent fuel pools of units 1–4 began to overheat as water levels in the pools dropped. Fears of radiation leaks led to a 20-kilometre (12 mi) radius evacuation around the plant. Workers at the plant suffered radiation exposure and were temporarily evacuated at various times. On 18 March, Japanese officials designated the magnitude of the danger at reactors 1, 2 and 3 at level 5 on the 7 point International Nuclear Event Scale (INES).[5] Power was restored to parts of the plant from 20 March, but machinery damaged by floods, fires and explosions remained inoperable.[6]

Measurements taken by the Japanese science ministry and education ministry in areas of northern Japan 30-50 km from the plant showed radioactive caesium levels high enough to cause concern.[7] Food grown in the area was banned from sale. An Austrian scientist has suggested that world wide measurements of iodine-131 and caesium-137 indicate that the releases from Fukushima are of the same order of magnitude as the releases of those isotopes from Chernobyl in 1986;[8] [9][10]reports of similar independent data do not make that claim.[11] [12] Tokyo officials temporarily recommended that tap water should not be used to prepare food for infants.[13][14] Plutonium contamination has been detected in the soil at two sites in the plant.[15]

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) announced on 27 March that workers hospitalized as a precaution on 25 March had been exposed to between 2 and 6 Sv of radiation at their ankles when standing in water in unit 3.[16][17][18] The international reaction to the accidents was also concerned. The Japanese government and TEPCO have been criticized for poor communication with the public.[19][20] On 20 March, the Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano announced that the plant would be decommissioned once the crisis was over. This was a forgone conclusion, as the use of sea water as an emergency coolant earlier on in the crisis would have the potential to cause cause corrosion which would make the plant inoperable.[21]

Summarised daily events

First week

- 11 March: 14:46 JST (05:46 UTC): Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami. The Japanese government declared a nuclear power emergency due to the failure of the reactor cooling systems in reactors of Fukushima I and evacuated thousands of residents living within 2 km of the reactor.[22][23]

- 12 March: While evidence of partial meltdown of the fuel rods in unit 1 was growing, a hydrogen explosion destroyed the roof of its reactor building. The explosion injured four workers, but the reactor containment inside remained intact.[24][25] Hydrogen and steam had been vented from the reactor to reduce pressure within the containment vessel and built up within the building.[26][27] Operators of the plant began using seawater for emergency cooling, which would permanently damage the reactor.[28] The evacuation zone was extended to 20 km, affecting 170,000–200,000 people, and the government advised residents within a further 10 km to stay indoors.[29][30] The release of fission products from the damaged reactor core, notably radioactive iodine-131, led Japanese officials to distribute prophylactic iodine to people living around Fukushima I and Fukushima II.[31] One worker was confirmed to be ill.

- 13 March: A partial meltdown was reported to be possible at unit 3.[32] As of 13:00 JST, both reactors 1 and 3 were being vented to release overpressure and re-filled with water and boric acid for cooling and inhibition of further nuclear reactions.[33] Unit 2 was possibly suffering lower than normal water level but was thought to be stable, although pressure inside the containment vessel was high.[33] The Japan Atomic Energy Agency announced that it was rating the situation at unit 1 as level 4 (accident with local consequences) on the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale.[2][34]

- 14 March: The reactor building for unit 3 exploded[35] injuring eleven people. There was no release of radioactive material beyond that already being vented but blast damage affected water supply to unit 2.[36] The president of the French nuclear safety authority, Autorité de sûreté nucléaire (ASN), said that the accident should be rated as a 5 (accident with wider consequences) or even a 6 (serious accident) on INES.[37]

- 15 March: Damage to temporary cooling systems on unit 2 by the explosion in unit 3 plus problems with its venting system meant that water could not be added, to the extent that unit 2 was in the most severe condition of the three reactors.[38] An explosion in the "pressure suppression room" caused some damage to unit 2’s containment system.[38][39] A fire broke out at unit 4 involving spent fuel rods from the reactor, which are normally kept in the water-filled spent fuel pool to prevent overheating. Radiation levels at the plant rose significantly but subsequently fell back.[40] Radiation equivalent dose rates at one location in the vicinity of unit 3 recorded 400 millisieverts per hour (400 mSv/h).[2][41][42]

- 16 March: At approximately 14:30 on 16 March, TEPCO announced its belief that the fuel rod storage pool of unit 4—which is located outside the containment area[43]—may have begun boiling, raising the possibility that exposed rods could reach criticality.[44] By midday, NHK TV was reporting white smoke rising from the Fukushima I plant, which officials suggested was likely coming from reactor 3. Shortly afterward, all but a small group[45] of remaining workers at the plant had been placed on standby because of the dangerously rising levels of radiation up to 1 Sv/h.[46][47] TEPCO had temporarily suspended operations at the facility due to radiation spikes and had pulled all their employees out.[48] A TEPCO press release stated that workers had been withdrawn at 06:00 JST because of abnormal noises coming from one of the reactor pressure suppression chambers.[49] Late in the evening, Reuters reported that water was being poured into reactors 5 and 6.[50]

- 17 March: During the morning, Self-Defense Force helicopters dropped water four times on the spent fuel pools of units 3 and 4.[51] In the afternoon it was reported that the unit 4 spent fuel pool was filled with water and none of the fuel rods were exposed.[52] Construction work was started to supply a working external electrical power source to all six units of Fukushima I.[53] Starting at 7 pm, police and fire water trucks with high pressure hoses attempted to spray water into the unit 3 reactor.[54] Japanese authorities informed the IAEA that engineers were laying an external grid power line cable to unit 2.[2]

Second week

- 18 March: Tokyo Fire Department dispatched thirty fire engines with 139 fire-fighters and a trained rescue team at approximately 03:00 JST. These included a fire truck with a 22 m water tower.[55] For the second consecutive day, high radiation levels had been detected in an area 30 kilometers (18.6 miles) northwest of the damaged Fukushima I nuclear plant. The reading was 150 microsieverts per hour.[56] Japanese authorities upgraded INES ratings for cooling loss and core damage at unit 1 to level 5 and issued the same rating for units 2 and 3.[2] The loss of fuel pool cooling water at unit 4 was classified as level 3.[2] In a 24-hour period ending at 11 am local time, radiation levels near the plant had declined from 351.4 to 265 μSv/h, but it was unclear if the water spraying efforts were the cause of the decrease.[57]

- 19 March: A second group of 100 Tokyo and 53 Osaka firefighters replaced the previous team. They used a vehicle that can project water from a height of 22 meters for cooling spent nuclear fuel storage pool inside the reactor of unit 3.[58][59] Water was sprayed into the reactor for a total of 7 hours during the day. TEPCO reported afterward that the water had been effective in lowering the temperature around the spent fuel rods to below 100°C.[60][verification needed]

- 20 March: External power was reconnected to unit 2 but work continued to make equipment operational. Repaired diesel generators at unit 6 provided power to restart cooling on units 5 and 6 which were returned to cold shutdown and their fuel cooling ponds returned to normal operating temperatures.[61][62][63] TEPCO announced that pressure in reactor 3's containment vessel was rising, and that it might be necessary to vent air containing radioactive particles to relieve pressure, Japanese broadcaster NHK reported at 1:06.[61][64][dead link] The operation was later aborted as TEPCO deemed it unnecessary.[61] While joining in a generally positive assessment of progress toward overall control, chief cabinet secretary Edano confirmed for the first time that the heavily damaged and contaminated complex would be closed once the crisis was over.[21]

- 21 March: Ongoing repair work was interrupted by a recurrence of grey smoke from the south-east side of unit 3 (the general area of the spent fuel pool) seen at 15:55 and dying down by 17:55. Employees were evacuated from unit 3 but no changes in radiation measurements or reactor status were seen. No work was going on at the time (such as restoring power) which might have accounted for the fire. White smoke, probably steam, was also seen coming from unit 2 at 18:22 JST, and this was accompanied by a temporary rise in radiation levels. A new power line was laid to unit 4 and unit 5 was transferred to its own external power from transmission line instead of sharing the unit 6 diesel generators.[65][66]

- 22 March: Smoke was still rising from units 2 and 3 but was less visible and was theorized to be steam following operations to spray water onto the buildings. Repair work resumed after having been halted because of concerns over the smoke, but no significant changes in radiation levels occurred so it was felt safe to resume work. Work continued to restore electricity, and a supply cable was connected to unit 4. Injection of seawater into units 1–3 continued.[67] External power cables were reported to be connected to all six units. Lighting was back on again in the control room of unit 3.[68][69]

- 23 March: In the late afternoon, smoke again started belching from reactor 3, this time black and grey smoke, causing another evacuation of workers from around the area. Aerial video from the plant showed what looked like a small fire at the base of the smoke plumes from within the heavily damaged reactor building. Feed water systems in unit 1 were restored increasing the rate water could be added to the reactor.[70] The Japanese Chief Cabinet Secretary also advised that high levels of radioactivity (around twice the legal limit for children) had been found in Tokyo's drinking water and that it should not be used to reconstitute baby formula.[71]

- 24 March: Seawater injection to units 1, 2 and 3 continued,[72] and radiation levels near the plant declined to 200 μSv/h.[73] Lighting was restored to the unit 1 control room.[74] Three workers were exposed to high levels of radiation which caused two of them to require hospital treatment after radioactive water seeped through their protective clothes.[75][76] The workers were exposed to an estimated equivalent dose of 2–6 Sv to the skin below their ankles.[77][78] They were not wearing protective boots, as their employing firm's safety manuals "did not assume a scenario in which its employees would carry out work standing in water at a nuclear power plant".[77] The amount of the radioactivity of the water was about 3.9 MBq/ml. Infra-red surveys of the reactor buildings by helicopter showed that temperatures of units 1, 2, 3 and 4 continued to decrease, ranging 11-17°C, and the fuel pool at unit 3 recorded 30°C.[79]

Third week

- 25 March: NISA announced a possible breach in the containment vessel of the unit 3 reactor, though radioactive water in the basement might alternatively have come the fuel storage pool.[80][81] Highly radioactive water was also found in the turbine buildings of units 1 and 2.[82] The US Navy sent a barge with 1,890 cubic metres (500,000 US gal) of fresh water, expected to arrive in two days.[83] Japan announced transportation would be provided in a voluntary evacuation zone of 30 kilometres (19 mi). Tap water was reported to be safe for infants in Tokyo and Chiba by Japanese authorities, but still exceeded limits in Hitachi and Tokaimura.[84] Iodine-131 in the ocean nearby measured 50 Bq/ml, a "relatively high" 1,250 times normal.[85]

- 26 March: Fresh water became available instead of seawater to top up reactor water levels.[86] The fresh water was provided by two United States Navy barges holding a total of 2,280 metric tons of fresh water which were towed by the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force from Yokosuka Naval Base to Fukushima.[87] Radiation levels near the plant had declined to a still high 170 μSv/h.[88]

- 27 March: Levels of "over 1000" and 750 mSv/h were reported from water within unit 2 (but outside the containment structure) and 3 respectively. A statement that this level was "ten million times the normal level" in unit 2 was later retracted and attributed to incorrectly high levels of iodine-134 (which was later reported to be below the limit by TEPCO).[89][90][91][92] Japan's Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency indicated that "The level of radiation is greater than 1,000 millisieverts. It is certain that it comes from atomic fission [...] But we are not sure how it came from the reactor."[93] The high radiation levels delayed technicians working to restore the water cooling systems for the troubled reactors.[94] USAF technicians at Yokota AB completed the fabrication of compatibility valves to allow the connection of deployed pump systems with the existing infrastructure at Fukushima.[95] An aerial video recorded by a Ground Self-Defense Force helicopter revealed according to NHK the clearest and most detailed view of the damaged plant to date. Significant observations included:[96]

- White vapour, possibly steam, emanating from the buildings of reactors 2, 3, and 4.

- The roof of the reactor 2 building has been badly damaged but is still intact.

- The reactor 3 building is largely uncovered, its roof blown off in a hydrogen explosion over two weeks prior.

- The walls of the reactor 4 building have also collapsed.

- 28 March: The Japanese Nuclear Safety Commission stated that it "assumed" melted fuel rods in unit 2 have released radioactive substances into cooling water which subsequently leaked out through an unknown route to the unit 2 turbine building basement.[97] To reduce the amount of water subject to leaking, TEPCO reduced the amount of water pumped into unit 2 reactor from 16 tons per hour to 7 ton per hour, which could lead to higher reactor temperatures.[97] The highly radioactive water halted work on restoring the cooling pumps and other powered systems to reactors 1-4.[98] TEPCO confirmed finding low levels of plutonium in five samples from 21 March and 22 March.[99] Enriched levels of Pu238 relative to Pu239 and Pu240 at two of the sites in the plant (solid waste area and field), indicated that contamination had occurred at those sites due to the “recent incident”. None the less, the overall levels of Pu for all samples were about the same as background Pu levels resulting from atmospheric nuclear bomb testing in the past.[15][100]

- 29 March: TEPCO continued to spray water into reactors 1–3 and discovered that radioactive runoff water was beginning to fill utility trenches outside the three reactor buildings. The highly radioactive water in and around the reactor buildings continued to limit progress by technicians in restoring the cooling and other automated systems to the reactors.[101]

- 30 March: TEPCO Chairman Tsunehisa Katsumata announced at a news conference that it was presently unclear how the problems at the plant would be resolved. An immediate difficulty was the removal of large quantities of radioactive water in basement buildings, but also salt built up inside the reactors from using seawater for cooling needed to be removed. Building new concrete walls around the reactors was being considered as had been done at Chernobyl.[102]

- 31 March: Workers pumped radioactive water from a utility trench near reactor No. 1. into a storage tank near reactor No. 4.[103] Water in the condensers for the No. 2 and No. 3 reactors was shifted to outside storage tanks so that the condensers could receive more contaminated water from the reactors.[104]

Fourth week

- 1 April: TEPCO said that groundwater near Unit 1 contained radioiodine at levels 10,000 times normal, but NISA later disputed the numbers.[105][106]

- 2 April: A crack leaking radioactive water into the ocean was discovered in pit housing electrical cables near the Unit 2 seawater inlet. Workers were preparing to pour concrete into the 20-centimetre (7.9 in) crack to stop the water, emitting radiation at 1000 mSv/h.[107][108]

Fukushima I Nuclear Power Plant

The Fukushima I Nuclear Power Plant consists of six light water, boiling water reactors (BWR) designed by General Electric driving electrical generators with a combined power of 4.7 gigawatts, making Fukushima I one of the 25 largest nuclear power stations in the world. Fukushima I was the first nuclear plant to be constructed and run entirely by the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO).

Unit 1 is a 439 MWe type (BWR3) reactor constructed in July 1967. It commenced commercial electrical production on 26 March 1971.[109] It was designed for a peak ground acceleration of 0.18 g (1.74 m/s2) and a response spectrum based on the 1952 Kern County earthquake.[110] Units 2 and 3 are both 784 MWe type BWR-4 reactors, unit 2 commenced operating in July 1974 and unit 3 in March 1976. The design basis for all units ranged from were 0.42 g (4.12 m/s2) and 0.46 g (4.52 m/s2).[111][112] All units were inspected after the 1978 Miyagi earthquake when the ground acceleration was 0.125 g (1.22 m/s2) for 30 seconds, but no damage to the critical parts of the reactor was discovered.[110]

Units 1–5 have a Mark 1 type (light bulb torus) containment structure, unit 6 has Mark 2 type (over/under) containment structure.[110] From September 2010, unit 3 has been fueled by mixed-oxide (MOX) fuel.[113]

At the time of the accident, the units and central storage facility contained the following numbers of fuel assemblies:[114]

Location Unit 1 Unit 2 Unit 3 Unit 4 Unit 5 Unit 6 Central Storage Reactor Fuel Assemblies 400 548 548 0 548 764 0 Spent Fuel Assemblies 292 587 514 1331 946 876 6375

Cooling requirements

Cooling is needed to remove decay heat from the reactor core even when a plant has been shut down.[115] Nuclear fuel releases a small quantity of heat under all conditions, but the chain reaction when a reactor is operating creates short lived decay products which continue to release heat despite shutdown.[116] Immediately after shutdown, this decay heat amounts to approximately 6% of full thermal heat production of the reactor.[115] The decay heat in the reactor core decreases over several days before reaching cold shutdown levels.[117] Nuclear fuel rods that have reached cold shutdown temperatures typically require another several years of water cooling in a spent fuel pool before decay heat production reduces to the point that they can be safely transferred to dry storage casks.[118]

In order to safely remove this decay heat, reactor operators must continue to circulate cooling water over fuel rods in the reactor core and spent fuel pond.[115][119] In the reactor core, circulation is accomplished by use of high pressure systems that pump water through the reactor pressure vessel and into heat exchangers. These systems transfer heat to a secondary heat exchanger via the essential service water system, taking away the heat which is pumped out to the sea or site cooling towers.[120]

To ensure that cooling water can continue to be circulated, reactors typically have redundant electrical supplies to operate pumps when the reactor is shutdown, including electric generators, electrical supplies from the grid, and batteries.[119][121] In addition, boiling water reactors have steam-turbine driven emergency core cooling systems that can be directly operated by steam still being produced after a reactor shutdown, which can inject water directly into the reactor.[122] Steam turbines results in less dependence on emergency generators, but steam turbines only operate so long as the reactor is producing steam, and some electrical power is still needed to operate the valves and monitoring systems.

If the water in the unit 4 spent fuel pool had been heated to boiling temperature, the decay heat has the capacity to boil off about 70 tonnes of water per day, which puts the requirement for cooling water in context.[123]

Direct effect of the earthquake and tsunami

The 9.0 MW Tōhoku earthquake resulted in maximum ground accelerations of 0.56, 0.52, 0.56 g (5.50, 5.07 and 5.48 m/s2) (well above the design basis of 0.45, 0.45 and 0.46 g (4.38, 4.41 and 4.52 m/s2)) at units 2, 3 and 5 respectively and values below the design basis at units 1, 4 and 6.[112] When the earthquake occured, reactor units 1, 2, and 3 were operating, but units 4, 5, and 6 had already been shut down for periodic inspection.[111][124] When the earthquake was detected, units 1, 2 and 3 underwent an automatic shutdown (called scram).[125]

After the reactors shut down, electricity generation stopped. Normally the plant could use an external electrical supply to power cooling and control systems,[126] but the earthquake caused major damage to the regional power grid. Emergency diesel generators started but stopped abruptly at 15:41, ending all AC power supply to the reactors. The plant was protected by a seawall which was designed to withstand a tsunami of 5.7 metres (19 ft), but the wave that struck the plant was estimated to be more than twice that height at 14 metres (46 ft). It easily topped the seawall, flooding the low-lying generator building.[127][128] Article 10 of the Japanese law on Special Measures Concerning Nuclear Emergency Preparedness, heightened alert condition requires authorities to be informed of such an incident: TEPCO did so immediately and also issued a press release declaring a "First Level Emergency".[125]

After the diesel generators failed, emergency power for control systems was supplied by batteries that were designed to last about eight hours.[23] Batteries from other nuclear plants were sent to the site and mobile generators arrived within 13 hours,[129] but work to connect portable generating equipment to power water pumps was still continuing as of 15:04 on 12 March.[22] Generators are connected through switching equipment in a basement area of the buildings, but this basement area had been flooded.[127] After subsequent efforts to bring water to the plant, plans shifted to a strategy of building a new power line and re-starting the pumps, eventually resulting in cable emplacement reported at approximately 08:30 UTC.[130]

TEPCO had not anticipated a tsunami as large or a quake as severe as the one that damaged the plant.[131][132] In addition to concerns from within Japan, the IAEA had previously expressed concern about the ability of Japan's nuclear plants to withstand seismic activity.[133]

Reactor unit 1

Cooling problems at unit 1 and first radioactivity release

On 11 March at 16:36 JST, a "Nuclear Emergency Situation" (Article 15 of the Japanese law on Special Measures Concerning Nuclear Emergency Preparedness) was declared when "the status of reactor water coolant injection could not be confirmed for the emergency core cooling systems of units 1 and 2." The alert was temporarily cleared when water level monitoring was restored for unit 1; it was reinstated at 17:07 JST.[134] Potentially radioactive steam was released from the primary circuit into the secondary containment area to reduce mounting pressure.[135]

After the loss of site power, unit 1 initially continued cooling using the isolation condenser system; by midnight water levels in the reactor were falling and TEPCO gave warnings of the possibility of radioactive releases.[136] In the early hours of 12 March TEPCO reported that radiation levels were rising in the turbine building for unit 1[137] and that it was considering venting some of the mounting pressure into the atmosphere, which could result in the release of some radioactivity.[138] Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano stated later in the morning the amount of potential radiation would be small and that the prevailing winds were blowing out to sea.[139] At 02:00 JST, the pressure inside the reactor containment was reported to be 600 kPa (6 bar or 87 psi), 200 kPa higher than under normal conditions.[128] At 05:30 JST the pressure inside reactor 1 was reported to be 2.1 times the "design capacity",[140] 820 kPa.[24] Isolation cooling ceased to operate between midnight and 11:00 JST at which point TEPCO started relieving pressure and injecting water.[141] One employee working inside unit 1 at this time received a radiation dose of 106 mSv and was later sent to hospital for checks.[142]

Rising heat within the containment area led to increasing pressure, with both cooling water pumps and ventilation fans for driving gases through heat exchangers within the containment dependent on electricity.[143] Releasing gases from the reactor is necessary if pressure becomes too high and has the benefit of cooling the reactor as water boils off; this also means cooling water is being lost and must be replaced.[127] If there was no damage to the fuel elements, water inside the reactor should be only slightly radioactive.

In a press release at 07:00 JST 12 March, TEPCO stated, "Measurement of radioactive material (iodine, etc.) by monitoring car indicates increasing value compared to normal level. One of the monitoring posts is also indicating higher than normal level."[144] Dose rates recorded on the main gate rose from 69 n Gy/h (for gamma radiation, equivalent to 69 n Sv/h) at 04:00 JST, 12 March, to 866 nGy/h (equivalent to 0.866 µSv/h) 40 minutes later, before hitting a peak of 385.5 μSv/h at 10:30 JST.[144][145][146][147] At 13:30 JST, workers detected radioactive caesium-137 and iodine-131 near reactor 1,[2] which indicated some of the core's fuel had been damaged.[148] Cooling water levels had fallen so much that parts of the nuclear fuel rods were exposed and partial melting might have occurred.[149][150] Radiation levels at the site boundary exceeded the regulatory limits.[151]

On 14 March radiation levels had continued to increase on the premises, measuring at 02:20 an intensity of 751 μSv/hour on one location and at 02:40 an intensity of 650 μSv/hour at another location on the premises.[152] On 16 March the maximum readings peaked at 10850 μSv/hour.[153]

Explosion of reactor 1 building

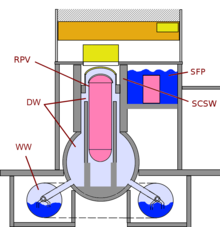

At 15:36 JST on 12 March there was an explosion at unit 1. Four workers were injured, and the upper shell of the reactor building was blown away leaving in place its steel frame.[154][155] The outer building is designed to provide ordinary weather protection for the areas inside, not to withstand the high pressure of an explosion or to act as containment for the reactor. In the Fukushima I reactors the primary containment consists of "drywell" and "wetwell" concrete structures immediately surrounding the reactor pressure vessel.[24][156]

Experts soon agreed the cause was a hydrogen explosion.[25][157][158] Almost certainly the hydrogen was formed inside the reactor vessel[25] because of falling water levels, and this hydrogen then leaked into the containment building.[25] Exposed zircaloy cladded fuel rods became very hot and reacted with steam, oxidising the alloy, and releasing hydrogen.[159] Safety devices normally burn the generated hydrogen when it is vented before explosive concentrations are reached but these systems failed, possibly due to the shortage of electrical power.

Officials indicated the container of the reactor had remained intact and there had been no large leaks of radioactive material,[24][25] although an increase in radiation levels was confirmed following the explosion.[160][161] ABC News (Australia) reported that according to the Fukushima prefectural government, radiation dose rates at the plant reached 1015 micro sievert per hour (1015 µSv/h).[162] The IAEA stated on 13 March that four workers had been injured by the explosion at the unit 1 reactor, and that three injuries were reported in other incidents at the site. They also reported one worker was exposed to higher-than-normal radiation levels but that fell below their guidance for emergency situations.[163]

Two independent nuclear experts cited design differences between the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant and the Fukushima I Nuclear Power Plant,[164][165] one of them saying he did not believe that a Chernobyl-style disaster will occur.[164]

Seawater used for cooling

At 20:05 JST on 12 March, the Japanese government ordered seawater to be injected into unit 1 in an ultimate effort to cool the reactor core.[22] The reactor would then have to be decommissioned because of contamination by salt and other impurities.[28] TEPCO started seawater cooling at 20:20, adding boric acid as a neutron absorber to prevent a criticality accident.[166][167] The water was to take five to ten hours to fill the reactor core, after which the reactor would cool down in around ten days.[25] The injection of seawater into the reactor pressure vessel was through the fire extinguisher system.[168][169] At 01:10 on 14 March injection of seawater was halted for two hours because all available water in the plant pools had run out (similarly, feed to unit 3 was halted).[168] NISA news reports stated 70% of the fuel rods had been damaged when uncovered.[170]

On 18 March a new electrical distribution panel was installed in an office adjacent to unit 1, to supply power via unit 2 when it was reconnected to the transmission grid two days later.[169][171] On 21 March injection of seawater continued, as did repairs to the control instrumentation.[2] On 23 March it became possible to inject water into the reactor using the feed water system rather than the fire extinguisher line, raising the flow rate from 2 to 18 m3/h (later reduced to 11m3/h),[70][172] and on 24 March lighting was restored to the central operating room.[173]

As of 24 March, the spent fuel pool was "thought to be fully or partially exposed", according to CNN.[174] Pressure in the reactor increased due to the seawater injection, resulting in steam discharges, later alleviated by reducing the water flow. Temperature increases were also reportedly temporary. TEPCO attributed some of the steam to water in the spent fuel pool. Pumping began to remove water contaminated with radioactive 137Cs and 131I from basement areas storing it in the condenser system.[173] By 29 March pumping was halted because condensate reservoirs were almost full and plans were being considered to transfer water to the suppression pool surge tanks.[175]

On 25 March fresh water became available again to be added to the reactor instead of salty water,[176] while work continued to repair the cooling system.[177] A volume of 1,890 cubic metres (500,000 US gal) of fresh water was brought to the plant by a barge provided by US Navy.[83] On 29 March the fire extinguishing system which had been used to inject water into the reactor was replaced by electrically-driven pumps.[173]

Possibility of criticality at unit 1

Reports of 13 observations of a neutron beams 1.5 km "southwest of the plant's No. 1 and 2 reactors" from 13 March to 16 March raised the possibility that nuclear fission could have occurred after the inital SCRAMing of the reactors at Fukushima Daiichi.[178] March 16 reports that fuel rods in the spent fuel pool at unit 4 could have been exposed appeared to indicate that fission may have occurred in that fuel pool.[179] Later reports of exceptionally high iodine-134 levels appeared to confirm this theory because iodine-134 was believed to be indicative of fission reactions.[180] However, later analysis showed the finding of very high levels of iodine-134 was erroneous, and not meaningful for explaining the neutron beam observations.[181] High measurements of chlorine-37 and chlorine-38 were also found in the now retracted TEPCO report.[182] The high chlorine levels caused some nuclear experts to calculate that fission may instead be occurring in unit 1.[183][184] Despite the accepted erroneous nature of the iodine-134 report, the IAEA appeared to accept the chlorine-based analysis as a possible theory for proving fission by stating "melted fuel in the No. 1 reactor building may be causing isolated, uncontrolled nuclear chain reactions" at a press conference.[185] Later isotope analysis released by TEPCO appeared to indicate no testing for chlorine but did show high levels of other possible fission products.[186][187] The possibility of ongoing fission is a concern, as it has been identified as an indication of higher risk "in Tokyo" and for workers.[180][188]

Reactor unit 2

Unit two was operating at the time of the earthquake and experienced the same controlled initial shutdown as the other units.[24] Diesel generators and other systems failed when the tsunami overran the plant. Reactor core isolation cooling system (RCIC) initially operated to cool the core but by midnight the status of the reactor was unclear; some monitoring equipment was still operating on temporary power.[136] Coolant level was stable and preparations were underway to reduce pressure in the reactor containment vessel should this become necessary, though TEPCO did not state in press releases what these were, and the government had been advised that this might happen.[141] RCIC was reported by TEPCO shut down around 19:00 JST on 12 March, but again reported to be operating as of 09:00 JST 13 March.[189] Pressure reduction of the reactor containment vessel commenced before midnight on 12 March[190] though IAEA reported as of 13:15 JST 14 March that according to information supplied to them, no venting had taken place at the plant.[2] A report in the New York Times suggested that plant officials initially concentrated efforts on a damaged fuel storage pool at unit 2, distracting attention from problems arising at the other reactors, but this incident is not reported in official press releases.[191] IAEA report that on 14 March at 09:30 RCIC was still operating and that power was being provided by a mobile generator.[2]

Cooling problems at unit 2

On 14 March, TEPCO reported the failure of the RCIC system.[192] Fuel rods had been fully exposed for 140 minutes and there was a risk of a core meltdown.[193] Reactor water level indicators were reported to be showing minimum values at 19:30 JST 14 March.[194]

At 22:29 JST, workers had succeeded in refilling half the reactor with water but parts of the rods were still exposed, and technicians could not rule out the possibility that some had melted. It was hoped that holes blown in the walls of reactor building 2 by the earlier blast from unit 3 would allow the escape of hydrogen vented from the reactor and prevent a similar explosion.[193] At 21:37 JST the measured dose rates at the gate of the plant reached a maximum of 3.13 millisievert per hour, which was enough to reach the annual limit for non-nuclear workers in twenty minutes,[193] but had fallen back to 0.326 millisieverts per hour by 22:35.[195]

It was believed that around 23:00 JST the 4 m long fuel rods in the reactor were fully exposed for the second time.[193][196] At 00:30 JST of 15 March, NHK ran a live press conference with TEPCO stating that the water level had sunk under the rods once again and pressure in the vessel was raised. The utility said that the hydrogen explosion at unit 3 might have caused a glitch in the cooling system of unit 2: Four out of five water pumps being used to cool unit 2 reactor had failed after the explosion at unit 3. In addition, the last pump had briefly stopped working when fuel ran out.[197][198] To replenish the water, the contained pressure would have to be lowered first by opening a valve of the vessel. The unit's air flow gauge was accidentally turned off and, with the gauge turned off, flow of water into the reactor was blocked leading to full exposure of the rods. As of 04:11 JST, 15 March, water was being pumped into the reactor of unit 2 again.[199]

Explosion in reactor 2 building

An explosion was heard after 06:14 JST[200] on 15 March in unit 2, possibly damaging the pressure-suppression system, which is at the bottom part of the containment vessel.[201][202] The radiation level was reported to exceed the legal limit and the plant's operator started to evacuate all non-essential workers from the plant.[203] Only a minimum crew of 50 men, also referred to as the Fukushima 50, was left at the site.[204] Soon after, radiation equivalent dose rates had risen to 8.2 mSv/h[205] around two hours after the explosion and again down to 2.4 mSv/h, shortly after.[206] Three hours after the explosion, the rates had risen to 11.9 mSv/h.[207]

While admitting that the suppression pool at the bottom of the containment vessel had been damaged in the explosion, causing a drop of pressure there, Japanese nuclear authorities emphasized that the containment had not been breached as a result of the explosion and contained no obvious holes.[208] In a news conference on 15 March the director general of the IAEA, Yukiya Amano, said that there was a "possibility of core damage" at unit 2, but "less than five percent".[209] NISA stated 33% of the fuel rods were damaged, in news reports the morning of 16 March.[170] On 30 March, Japan's Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency (JNISA) reiterated concerns about a possible unit 2 breach at either the supression pool, or the reactor vessel.[210] NHK World reported the JNISA's concerns as "air may be leaking," very probably through "weakened valves, pipes and openings under the reactors where the control rods are inserted," but that "there is no indication of large cracks or holes in the reactor vessels."[210]

Continuing radiation

By midday on 19 March grid power had been connected to the existing transformer at unit 2 and work continued to connect the transformer to the new distribution panel installed in a nearby building.[211] Outside electricity became available at 15:46 JST on 20 March, but equipment still had to be repaired and reconnected.[169]

On 20 March, 40 tons of seawater were added to the spent fuel pool.[169] The temperature in the spent fuel pool was 53°C as of 22 March 11:00 JST.[212] The Japan Atomic Industrial Forum reported "high radiation readings" in the area.[174]

Unit 2 was considered the most likely unit to have a damaged reactor containment vessel, as of 24 March.[174] On 27 March, TEPCO reported measurements of very high radiation levels of over 1000 mSv/h in the basement of the unit 2 turbine building, which officials reported was 10 million times higher than what would be found in the water of a normally functioning reactor. Hours into the media frenzy, the company retracted its report and stated that the figures were not credible.[213] "because the level was so high the worker taking the reading had to evacuate before confirming it with a second reading."[214] Shortly following the ensuing wave of media retractions that discredited the report worldwide, TEPCO clarified its initial retraction; the radiation from the pool surface in the basement of the unit 2 turbine building was found to be "more than 1,000 millisieverts per hour," as originally reported, but the concentration of radioactive substances was 100,000 times higher than usual, not 10 million.[215] On 28 March, the Nuclear Safety Commission announced its suspicion that "radioactive substances from temporarily melted fuel rods at the No. 2 reactor had made their way into water in the reactor containment vessel and then leaked out through an unknown route". Tepco subsequently reduced the introduced amount of water from 16 to 7 ton per hour, which could lead to higher temperatures in the reactor.[97] Highly radioactive water was also found in three "trenches" which stretch toward, but do not connect to, the sea.[97][216] The unit 2 trench was 1 m below the level where it would overflow to the sea, in comparison, the unit 3 was at the same water level, while the unit 1 trench was 10 cm from overflowing, TEPCO used "sandbags and concrete" to prevent an overflow.[216] The high levels of water in the trenches combined with their potential to overflow to the sea complicated cooling efforts because water is required to cool the reactor, however, the same water is believed to be filling the trenches.[217] Hence, cooling unit 2 with large quantities of fresh water was expected to cause the trenches, leading to the sea, to fill and overflow—worsening the radiation release.[217] On 29 March water transfers began to remove water from the condensate reservoirs to the suppresion pool surge tanks, to make space for flood water to be pumped into condensers.[175]

On 27 March, the IAEA reported temperatures at the bottom of the Reactor Pressure Vessel (RPV) at unit 2 fell to 97°C from 100°C on Saturday. Operators attempted to pump water from the turbine hall basement to the condenser.[218][219] However, "both condensers turned out to be full."[220] Therefore, condenser water was first attempted to be pumped to storage tanks, freeing condenser storage for water currently in the basement of unit 2.[220] Pumps now being used can move 10 to 25 tons of water per hour.[220]

On 29 March, Richard Lahey, former head of safety research for boiling-water reactors at General Electric, speculated that the reactor core could have possibly melted through the reactor vessel onto a concrete floor, raising concerns of a major release of radioactive material.[221]

Reactor unit 3

Unlike the other five reactor units, reactor 3 runs on mixed uranium and plutonium oxide, or MOX fuel, making it potentially more dangerous in an incident due to the neutronic effects of plutonium on the reactor, the very long half-life of plutonium's radioactivity, and the carcinogenic effects[222] in the event of release to the environment.[150][223][224] Units 3 and 4 have a shared control room.[225]

Cooling problems at unit 3

Early on 13 March an official of the Japan Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency told a news conference that the emergency cooling system of unit 3 had failed, spurring an urgent search for a means to supply cooling water to the reactor vessel in order to prevent a meltdown of its reactor core.[226] At 05:38 there was no means of adding coolant to the reactor due to loss of power. Work to restore power and vent pressure continued.[227] At one point, the top three meters of mixed oxide (MOX) fuel rods were not covered by coolant.[228]

At 07:30 JST, TEPCO prepared to release radioactive steam, indicating that "the amount of radiation to be released would be small and not of a level that would affect human health"[229] and manual venting took place at 08:41 and 09:20.[230] At 09:25 JST on 13 March, operators began injecting water containing boric acid into the primary containment vessel (PCV) via a fire pump.[231][232] When water levels continued to fall and pressure to rise, the injected water was switched to seawater at 13:12.[227] By 15:00 it was noted that despite adding water the level in the reactor did not rise and radiation had increased.[233] A rise was eventually recorded but the level stuck at 2 m below the top of reactor core. Other readings suggested that this could not be the case and the gauge was malfunctioning.[230]

Injection of seawater into the PCV was discontinued at 01:10 on 14 March because all the water in the reserve pool had been used up. Supplies were restored by 03:20 and injection of water resumed.[232] On the morning of 15 March, Secretary Edano announced that according to TEPCO, at one location near reactor units 3 and 4, radiation at an equivalent dose rate of 400 mSv/h was detected.[2][41][42] This might have been due to debris from the explosion in unit 4.[234]

Explosion of reactor 3 building

At 12:33 JST on 13 March, the chief spokesman of the Japanese government, Yukio Edano said hydrogen was building up inside the outer building of unit 3 just as had occurred in unit 1, threatening the same kind of explosion.[235] At 11:15 JST on 14 March, the envisaged explosion of the building surrounding reactor 3 of Fukushima 1 occurred, due to the ignition of built up hydrogen gas.[236][237] The Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency of Japan reported, as with unit 1, the top section of the reactor building was blown apart, but the inner containment vessel was not breached. The explosion was larger than that in unit 1 and felt 40 kilometers away. Pressure readings within the reactor remained steady at around 380 kPa at 11:13 and 360 kPa at 11:55 compared to nominal levels of 400 kPa and a maximum recorded of 840 kPa. Water injection continued. Dose rates of 0.05 mSv/h were recorded in the service hall and of 0.02 mSv/h at the plant entrance.[238] It was reported that day that eleven people were injured in the blast.[239] Six soldiers from the Japanese Central Nuclear Biological Chemical Weapon Defence Unit are reported to have been killed in the explosion.[240]

Spent fuel pool

Around 10:00 JST, 16 March, NHK helicopters flying 30 km away videotaped white fumes rising from the Fukushima I facility. Officials suggested that the reactor 3 building was the most likely source, and said that its containment systems may have been breached.[241] The control room for reactors 3 and 4 was evacuated at 10:45 JST but staff were cleared to return and resume water injection into the reactor at 11:30 JST.[225] At 16:12 JST Self Defence Force (SDF) Chinook helicopters were preparing to pour water on unit 3, where white fumes rising from the building was believed to be water boiling away from the fuel rod cooling pond on the top floor of the reactor building, and on unit 4 where the cooling pool was also short of water. The mission was cancelled when helicopter measurements reported radiation levels of 50 mSv.[242][243] At 21:06 pm JST government reported that major damage to reactor 3 was unlikely but that it nonetheless remained their highest priority.[244]

Early on 17 March, TEPCO requested another attempt by the military to put water on the reactor using a helicopter[245] and four helicopter drops of seawater took place around 10:00 JST.[246] The riot police used a water cannon to spray water onto the top of the reactor building and then were replaced by members of the SDF with spray vehicles. On 18 March a crew of firemen took over the task with six fire engines each spraying 6 tons of water in 40 minutes. 30 further hyper rescue vehicles were involved in spraying operations.[247] Spraying continued each day to 23 March because of concerns the explosion in unit 3 may have damaged the pool (total 3,742 tonnes of water sprayed up to 22 March) with changing crews to minimise radiation exposure.[2] Lighting in the control room was restored on 22 March after a connection was made to a new grid power supply and by 24 March it was possible to add 35 tonnes of seawater to the spent fuel pool using the cooling and purification system.[172] Grey smoke was reported to be rising from the southeast corner of unit 3 on 21 March. The spent fuel pool is located at this part of the building. Workers were evacuated from the area. TEPCO claimed no significant change in radiation levels and the smoke subsided later the same day.[248]

On 23 March, black smoke billowed from unit 3, prompting another evacuation of workers from the plant, though Tokyo Electric Power Co. officials said there had been no corresponding spike in radiation at the plant. "We don't know the reason for the smoke", Hidehiko Nishiyama of the Nuclear Safety Agency said.[249]

Possible breach

On 25 March, officials announced the reactor vessel might be breached and leaking radioactive material. High radiation levels from contaminated water prevented work.[250] Japan's Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency (JNISA) reiterated concerns about a unit 3 breach on 30 March.[210] NHK World reported the JNISA's concerns as "air may be leaking," very probably through "weakened valves, pipes and openings under the reactors where the control rods are inserted," but that "there is no indication of large cracks or holes in the reactor vessels."[210] As with the other reactors, water was transferred from condenser reservoirs to the suppression pool surge tanks so that condensers could be used to hold radioactive water pumped from the basement.[175]

Reactor unit 4

At the time of the earthquake unit 4 had been shut down for a scheduled periodic inspection since 30 November 2010. All 548 fuel rods had been transferred in December 2010 from the reactor to the spent fuel pool on an upper floor of the reactor building[251] where they were held in racks containing boron to damp down any nuclear reaction.[234] The pool is used to store rods for some time after removal from the reactor and now contains 1,479 rods.[252] Recently active fuel rods produce more decay heat than older ones.[253] At 04:00 JST on Monday 14 March, water in the pool had reached a temperature of 84°C compared to a normal value of 40–50°C.[234] The IAEA was advised that the temperature value remained 84°C at 19:00 JST on 15 March, but as of 18 March, no further information was reported.[2][168]

Explosion of reactor 4 building

At approximately 06:00 JST on 15 March, an explosion—thought to have been caused by hydrogen accumulating near the spent fuel pond—damaged the 4th floor rooftop area of the unit 4 reactor as well as part of the adjacent unit 3.[254][255] At 09:40, the unit 4 spent fuel pool caught fire, likely releasing radioactive contamination from the fuel stored there.[256][257] TEPCO said workers extinguished the fire by 12:00.[258][259] As radiation levels rose, some of the employees still at the plant were evacuated.[260] On the morning of 15 March, Secretary Edano announced that according to the TEPCO, radiation dose equivalent rates measured from the unit 4 reached 100 mSv/h.[41][42] Edano said there was no continued release of "high radiation".[261]

Japan's nuclear safety agency NISA reported two holes, each 8 meters square, or 64 square metres (690 sq ft), in a wall of the outer building of unit 4 after the explosion.[262] At 17:48 it was reported that water in the spent fuel pool might be boiling.[263][264] By 21:13 on 15 March, radiation inside the unit 4 control room prevented workers from staying there permanently.[265] Seventy staff remained at the plant, while 800 had been evacuated.[266] By 22:30, TEPCO was reportedly unable to pour water into the spent fuel pool.[234] By 22:50, the company was considering using helicopters to drop water,[266][267][268] but this was postponed because of concerns over safety and effectiveness, and the use of high-pressure fire hoses was considered instead.[269]

A fire was discovered at 05:45 JST on 16 March in the northwest corner of the reactor building by a worker taking batteries to the central control room of unit 4.[270][271] This was reported to the authorities, but on further inspection at 06:15 no fire was found. Other reports stated that the fire was under control.[272] At 11:57 TEPCO released a photograph showing "a large portion of the building's outer wall has collapsed."[273] Technicians considered spraying boric acid on the building from a helicopter.[274][275]

On 18 March, it was reported that water sprayed into the spent fuel pool was disappearing faster than evaporation could explain, suggesting leakage.[276][277] SDF military trucks sprayed water onto the building to try to replenish the pool on 20 March.[63] On 22 March, the Australian military flew in Bechtel-owned robotic equipment for remote spraying and viewing of the pool. The Australian reported this would give the first clear view of the pool in the "most dangerous" of the reactor buildings.[278]

Possibility of criticality in the spent fuel pool

At approximately 14:30 on 16 March, TEPCO announced that the storage pool, located outside the containment area,[43] might be boiling, and if so the exposed rods could reach criticality.[44][280] The BBC commented that criticality would not mean a nuclear bomb-like explosion, but could cause a sustained release of radioactive materials.[44] Around 20:00 JST it was planned to use a police water cannon to spray water on unit 4.[281]

On 16 March, the chairman of United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), Gregory Jaczko, said in Congressional testimony that the NRC believed all of the water in the spent fuel pool had boiled dry.[282][283] Japanese nuclear authorities and TEPCO contradicted this report, but later in the day Jaczko stood by his claim saying it had been confirmed by sources in Japan.[284] At 13:00 TEPCO claimed that helicopter observation indicated that the pool had not boiled off.[285] The French Institut de Radioprotection et de Sûreté Nucléaire (IRSN) agreed, stating that helicopter crews diverted planned water dumps to unit 3 on the basis of their visual inspection of unit 4.[286]

The IAEA reported, "From March 22 to March 25, 130 to 150 tonnes of seawater were poured into the spent fuel pool each day using a concrete pump equiped with a long articulated arm. Seawater was also poured in through spent fuel cooling system from 21:05 UTC 24 March to 01:20 25 March. White smoke was still being observed coming from the reactor building as of 23:00 UTC 25 March."[287] On 29 March, the seawater was changed to fresh water.[288]

Reactor units 5 and 6

Both reactors were off line at the time the earthquake struck (reactor 5 had been shut down on 3 January 2011 and reactor 6 on 14 August 2010), although they were still fueled, unlike reactor 4 where the fuel rods had been removed prior to the earthquake.[252]

Government spokesman Edano stated on 15 March that reactors 5 and 6 were being closely monitored, as cooling processes were not functioning well.[261][289] At 09:16 JST the removal of roof panels from reactor buildings 5 and 6 was being considered in order to allow any hydrogen build-up to escape.[2] At 21:00 on 15 March, water levels in unit 5 were reported to be 2 m above fuel rods, but were falling at a rate of 8 cm per hour.[2]

On 17 March, unit 6 was reported to have operational diesel-generated power and this was to be used to power pumps in unit 5 to run the Make-up Water Condensate System (MUWC) to supply more water.[2] Preparations were made to inject water into the reactor pressure vessel once external power could be restored to the plant, as water levels in the reactors were considered to be declining.[2] It was estimated that grid power might be restored on 20 March through cables laid from a new temporary supply being constructed at units 1 and 2.[290]

Information provided to the IAEA indicated that storage pool temperatures at both units 5 and 6 remained steady around 60–68°C between 19:00 JST 14 March and 21:00 JST 18 March, though rising slowly.[2] On 18 March reactor water levels remained around 2 m above the top of fuel rods.[168][290] It was confirmed that panels had been removed from the roofs of units 5 and 6 to allow any hydrogen gas to escape.[2] At 04:22 on 19 March the second unit of emergency generator A for unit 6 was restarted which allowed operation of pump C of the residual heat removal system (RHR) in unit 5 to cool the spent fuel storage pool.[291] Later in the day pump B in unit 6 was also restarted to allow cooling of the spent fuel pool there.[2][292] Temperature at unit 5 pool decreased to 48°C on 19 March 18:00 JST,[293] and 37°C on 20 March when unit 6 pool temperature had fallen to 41°C.[63] On 20 March NISA announced that both reactors had been returned to a condition of cold shutdown.[65] External power was partially restored to unit 5 via transformers at unit 6 connected to the Yonoromi power transmission line on 21 March.[65]

On 23 March, it was reported that the cooling pump at reactor No 5 stopped working when it was transferred from backup power to the grid supply.[294][295] This was repaired and the cooling restarted approximately 24 hours later. RHR cooling in unit 6 was switched to the permanent power supply on 25 March.[296]

Central fuel storage areas

Used fuel assemblies taken from reactors are initially stored for at least 18 months in the pools adjacent to their reactors. They can then be transferred to the central fuel storage pond.[2] This contains 6375 fuel assemblies and was reported "secured" with a temperature of 55°C. After further cooling, fuel can be transferred to dry cask storage, which has shown no signs of abnormalities.[297] On 21 March temperatures in the fuel pond had risen a little to 61°C and water was sprayed over the pool.[2] Power was restored to cooling systems on 24 March and by 28 March temperatures were reported down to 35°C.[173]

Radiation levels and radioactive contamination

Radioactive material was released from containment on several occasions after the tsunami struck, the result of deliberate venting to reduce gaseous pressure, deliberate discharge of coolant water into the sea, and accidental or uncontrolled events. Using Japanese Nuclear Safety Commission numbers, Asahi Shimbun reported that by 24 March the accident might have emitted 30,000 to 110,000 TBq of iodine-131.[298] The highest reported radiation dose outside was was on 16 March, prompting a temporary evacuation of plant workers 1000 mSv/h[46] On 29 March, at times near unit 2, radiation monitoring was hampered by a belief that some radiation levels may be higher than 1000 mSv/hr, but that "1,000 millisieverts is the upper limit of their measuring devices."[217] The maximum permissible dose for Japanese nuclear workers was increased to 250 mSv/year, for emergency situations after the accidents.[299][300]

The Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare announced that levels of radioactivity exceeding legal limits had been detected in milk produced in the Fukushima area and in certain vegetables in Ibaraki. Measurements made by Japan in a number of locations have shown the presence of radionuclides on the ground.[301] On 23 March, Tokyo drinking water exceeded the safe level for infants, prompting the government to distribute bottled water to families with infants.[302] Seawater near the discharge of the plant elevated levels of iodine-131 were found on 22 March, which had increased to 3,355 times the legal limit on 29 March. Also concentrations far beyond the legal limit were measured for cesium-134 and cesium-137 were more than 100 times above the limit.

Accident rating

The severity of a nuclear accident is rated on the International Nuclear Event Scale (INES). This scale runs from 0, indicating an abnormal situation with no safety consequences, to 7, indicating an accident causing widespread contamination with serious health and environmental effects. The Chernobyl disaster is the only level 7 accident on record, while the Three Mile Island accident was a level 5 accident.

The Japan Atomic Energy Agency initially rated the situation at unit 1 below both of these previous accidents; on 13 March it announced it was classifying the event at level 4, an "accident with local consequences".[34] On 18 March it raised its rating on unit 1 to level 5, an "accident with wider consequences", and also assigned this rating to the accidents at units 2 and 3. It classified the situation at unit 4 as a level 3 "serious incident".[303]

The Wall Street Journal reported on 25 March that authorities were considering raising the event to level 6, a "serious accident," one level above the Three Mile Island accident, and second only to Chernobyl.[304] On the same day, Asahi Shimbun supported this upgrading, based on the amount of radioactive contamination.[298][305]

Several parties have disputed the Japanese classifications, arguing that the situation is more severe than they are admitting. On 14 March, three Russian experts stated that the nuclear accident should be classified at Level 5, perhaps even Level 6.[306] One day later, the French nuclear safety authority ASN said that the Fukushima plant could be classified as a Level 6.[307] as of 18 March[update], the French nuclear authority—and as of 15 March, the Finnish nuclear safety authority—estimated the accidents at Fukushima to be at Level 6 on the INES.[308][309] On 24 March, a scientific consultant for Greenpeace, a noted anti-nuclear environmental group, working with data from the Austrian ZAMG[310] and French IRSN, prepared an analysis in which he rated the total Fukushima I accident at INES level 7.[311]

Health consequences

A study by British scientist and activist Chris Busby estimated that according to the ECRR model, a total of 417,000 cases of cancer can be expected from Fukushima fallout within a 200 km radius of the plant. Assuming permanent residence and no evacuation the total predicted yield is 224,223 cases of cancer in ten years. However, according to Busby, the ICRP guidelines predict a total number of cancer cases as a result of Fukushima of 3,320. This discrepancy is caused by differing views on the health effects of low-level radiation.[312]

Reaction in Japan and evacuation measures

A nuclear emergency was declared by the Government at 19:03 on 11 March. Later Prime Minister Naoto Kan issued instructions that people within a 20 km (12 mile) zone around the plant must leave, and urged that those living between 20 km and 30 km from the site to stay indoors.[313][314] The latter zone was later subject to voluntary evacuation. The Prime Minister visited the plant for a briefing on 12 March.[315] He called for calm and against exaggerating the danger.[316]

On 30 March the IAEA discovered 20 MBq/m2 of Iodine-131 samples taken from 18 to 26 March in Iitate, Fukushima, 40 km northwest of the Fukushima I reactor. The IAEA recommended expanding the evacuation area, based on its criteria of 10 MBq/m2. Secretary Edano stated the government would wait to see if the high radiation continued.[317] On 31 March, the IAEA announced a new value of 7 MBq/m2, in samples taken from 19 to 29 March in Iitate.[318] The material decays at 8% to 9% each day.

International reaction

The international reaction to the nuclear accidents has been a humanitarian response to the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, also to those people affected by the events at Fukushima I. The response has also included the expression of concern over the developments at the reactors and the risk of escalation. The accidents have furthermore prompted re-evaluation of existing and planned national nuclear energy programs, with some commentators questioning the future of the nuclear renaissance.[319][320][321][322]

USA, Australia and Sweden have instructed their citizens to evacuate a radius of minimum 80 km. Spain has advised their citizens to leave an area of 120 km, Germany has advised their citizens to leave even the metropolitan area of Tokyo, and South Korea advises to leave farther than 80 km and to have plans to evacuate by all possible means.[323][324] Travel to Japan is very low, but additional flights have been chartered by some countries to assist those who wish to leave. Official evacuation of Japan has been started by several nations.[325]

Reactor status summary

| No immediate concern | Concern | Severe Condition |

| Status of Fukushima I at 2 April 18:00 JST[328] | Unit 1 | Unit 2 | Unit 3 | Unit 4 | Unit 5 | Unit 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rated Electrical Power output (MWe) | 460 | 784 | 784 | 784 | 784 | 1,100 |

| Rated Thermal Power output (MWt) | 1,380 | 2,381 | 2,381 | 2,381 | 2,381 | 3,293 |

| Type of reactor | BWR-3 | BWR-4 | BWR-4 | BWR-4 | BWR-4 | BWR-5 |

| Containment type | Mark I | Mark I | Mark I | Mark I | Mark I | Mark II |

| Core fuel assemblies[330] | 400 | 548 | 548 | 0[252] | 548 | 764 |

| Spent fuel assemblies[252] | 292 | 587 | 514 | 1,331 | 946 | 876 |

| Spent fuel residual decay heat[331][332] | 60 kW | 400 kW | 200 kW | 2,000 kW | 700 kW | 600 kW |

| Fuel type | Low-enriched uranium | Low-enriched uranium | Mixed-oxide (MOX) and low-enriched uranium | Low-enriched uranium | Low-enriched uranium | Low-enriched uranium |

| Status at earthquake | In service | In service | In service | Outage (scheduled) | Outage (scheduled) | Outage (scheduled) |

| Fuel integrity | Damaged | Damaged | Damaged | Spent fuel possibly damaged | Not damaged | Not damaged |

| Reactor pressure vessel integrity | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Not damaged (defueled) | Not damaged | Not damaged |

| Containment integrity | Not damaged (estimation) | Damage and leakage suspected | Not damaged (estimation) | Not damaged | Not damaged | Not damaged |

| Core cooling system 1 (ECCS/RHR) | Not functional | Not functional | Not functional | Not necessary (defueled) | Functional | Functional |

| Core cooling system 2 (RCIC/MUWC) | Not functional | Not functional | Not functional | Not necessary (defueled) | Functional (in cold shutdown) | Functional (in cold shutdown) |

| Building integrity | Severely damaged due to hydrogen explosion | Slightly damaged, also panel removed to prevent hydrogen explosion | Severely damaged due to hydrogen explosion | Severely damaged due to hydrogen explosion | Panel removed to prevent hydrogen explosion | Panel removed to prevent hydrogen explosion |

| Pressure vessel, water level | Fuel exposed partially or fully | Fuel exposed partially or fully | Fuel exposed partially or fully | Safe (defueled) | Safe (in cold shutdown) | Safe (in cold shutdown) |

| Pressure vessel, pressure | Gradually increasing | Unknown | Unknown | Safe (defueled) | Safe (in cold shutdown) | Safe (in cold shutdown) |

| Pressure vessel, temperature | Slightly decreased after increasing over 400°C on 24 March | Stable | Unknown | Safe (defueled) | Safe (in cold shutdown) | Safe (in cold shutdown) |

| Containment pressure | Slightly decreased after increasing up to 0.4 MPa on 24 March | Stable | Stable | Safe | Safe | Safe |

| Seawater injection into core | Continuing (switched to freshwater) | Continuing (switched to freshwater) | Continuing (switched to freshwater) | Not necessary (defueled) | Not necessary | Not necessary |

| Seawater injection into containment vessel | To be decided | Performed 19 March[333] | To be decided | Not necessary | Not necessary | Not necessary |

| Containment venting | Temporarily stopped | Temporarily stopped | Temporarily stopped | Not necessary | Not necessary | Not necessary |

| INES | Level 5 | Level 5 | Level 5 | Level 3 | – | – |

| Environmental effect |

| |||||

| Evacuation radius | 20 km from Nuclear Power Station (NPS), but 30 km should consider leaving as of 25 March[334] | |||||

| General status from all sources regarding reactor cores | Stabilized by injecting sea water and boron[335] | Stabilized by injecting sea water and boron[335] | Stabilized by injecting sea water and boron; pressure elevated on 20 March[335] | Defueled | Cold shutdown on 20 March 14:30 JST[61][335] | Cold shutdown on 20 March 19:27 JST[61][335] |

| General status from all sources regarding Spent Fuel Pools (SFP) | Sprayed freshwater injection started, 60°C on 20 March by infrared helicopter measurement[336] | Freshwater injection continues, 48°C on 1 April 06:00 JST[337] | Sprayed freshwater injection continues, 60°C on 20 March by infrared helicopter measurement[336] | Sprayed freshwater injection continues after hydrogen explosion from pool on 15 March, 40°C on 20 March by infrared helicopter measurement[336] | Cooling system restored, 36.6°C on 1 April 06:00 JST[337] | Cooling system restored, 22.0°C on 1 April 06:00 JST[337] |

| Information sources[328][329][338][339][340][341][342][343][344][345][346][347][348][349][350][351][352][353][354][355][356][357] | ||||||

Solutions considered or attempted

Solutions attempted

| Effective | Partially effective | Not effective | Not applicable or unknown |

| Solution attempted | General effectiveness | Specific effectiveness | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactor cores | Spent fuel pools | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |||

| Backup diesel generators

The built-in backup diesel generators operated initially. |

All generators failed when the 14 meter tsunami overtopped tsunami walls designed for a 5.7 m tsunami. One generator repaired 17 March at units 5 and 6[358] to cool spent fuel pools.[359] A second on 19 March powered reactor cooling and reactors 5 and 6 were brought back to cold shutdown.[326] | |||||||||||||

| Backup batteries

The built-in backup batteries maintained some control functions and limited cooling for 8 hours after the generators failed.[360] |

Effective but only designed to work for 8 hours.[360] The operators were unable to connect portable generators before the 8 hours ran out. Note, limited cooling was not designed to stabilise reactors indefinitely, even if batteries were recharged.[360] | |||||||||||||

| Mobile power units

After the power loss due to the earthquake and tsunami, mobile power units were sent to the plant.[358][361] |

Flooding of plant prevented mobile generators being connected and sufficiently large units were not available | Some central monitoring systems | ||||||||||||

| Repair power lines to provide electricity

1 km of new grid cable and replacement switchgear was installed to provide power to plant.[335][362][363] |

Power was connected to the distribution panels of Units 2 and 5 on Sunday 20 March and power is now available to Units 1, 2, 5 and 6[363][364][365][366][367][368][369] but only equipment in units 5 and 6 is sufficiently repaired to function.

Units 3 and 4 are scheduled to have electricity connected to their distribution panels on 22 March.[370] |

Central control room | ||||||||||||

| Emergency cooling systems

The built-in Emergency cooling systems (ECCS) include: High Pressure Coolant Injection System (HPCI), Reactor Core Isolation Cooling System (RCIC), Automatic Depressurization System (ADS), Low Pressure Core Spray System (LPCS), Low Pressure Coolant Injection System (LPCI), Depressurization Valve System (DPVS), Passive Containment Cooling System (PCCS), and Gravity Driven Cooling System (GDCS).[360] |