Go (game): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{otheruses|Go}} |

|||

{{redirect|Goe|other uses|GOE}} |

{{redirect|Goe|other uses|GOE}} |

||

{{Infobox Game |

{{Infobox Game |

||

Revision as of 10:15, 17 April 2011

Go is played on a grid of black painted lines (usually 19×19). The playing pieces, called stones, are played on the intersections of the lines. | |

| Players | 2 |

|---|---|

| Setup time | Virtually none |

| Playing time | Casual: 20–90 minutes Tournament: 1–6 hours[a] |

| Chance | None |

| Age range | PCs: 3+; real board: 6+[1] |

| Skills | Tactics, strategy, observation |

| 1 Some professional games, especially in Japan, take more than 16 hours and are played in sessions spread over two days. | |

| Go | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 圍棋 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 围棋 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||

| Tibetan | མིག་མངས | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||

| Hangul | 바둑 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||

| Kanji | 碁, 囲碁 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Go (Japanese:碁), known as weiqi in Chinese and baduk in Korean, is an ancient board game for two players that originated in China more than 2,000 years ago. The game is noted for being rich in strategy despite its relatively simple rules (see Rules of Go).

The game is played by two players who alternately place black and white stones on the vacant intersections (called "points") of a grid of 19×19 lines. Once placed on the board, stones cannot be moved elsewhere, unless they are surrounded and captured by the opponent's stones. The object of the game is to secure (surround) a larger portion of the board than the opponent. When a game concludes, the controlled points (territory) are counted along with captured stones (there are different ways to count the score, depending on the rule-set) and a predetermined compensation ("komi") to determine who has more points. Games may also be won by resignation, if for example one side has suffered a severe tactical loss (too many stones captured, etc.).

Placing stones close together usually helps them support each other and avoid capture; on the other hand, placing stones far apart creates influence across more of the board. Part of the strategic difficulty of the game stems from finding a balance between such conflicting interests. Players strive to serve both defensive and offensive purposes and choose between tactical urgency and strategic plans. At its basis, the game is one of simple logic, while in advanced play the game involves complex heuristics and tactical analysis. Beginning players first learn the simple mechanics of how stones interact, while intermediate students learn concepts such as initiative ("sente"), influence, and the proper timing of moves.

Go originated in ancient China sometime before the 3rd century BC (exactly when is unknown), by which time it was already a popular pastime, as indicated by a reference to the game in the Analects of Confucius. Archaeological evidence shows that the early game was played on a board with a 17×17 grid, but by the time that the game spread to Korea and Japan in about the 5th and 7th centuries respectively, the boards with a 19×19 grid had become standard.

The game is most popular in East Asia. An estimate done in 2003 places the number of Go players worldwide at approximately 27 million.[2] Go reached the West through Japan, which is why it is commonly known internationally by its Japanese name.[nb 1]

Rules

Although there are some minor differences between rule sets used in different countries,[3] most notably in Chinese and Japanese scoring rules,[4] these differences do not seriously affect the tactics and strategy of the game. Except where noted otherwise, the basic rules presented here are valid independent of the scoring rules used. The scoring rules are explained separately. Go concepts for which there is no ready English equivalent are commonly called by their Japanese names.

Basic rules

Two players, Black and White, take turns placing a stone (game piece) of their own color on a vacant point (intersection) of the grid on a Go board. Black moves first. If there is a large difference in skill between the players, Black is sometimes allowed to place two or more stones on the board for their first move - see Go handicaps for details. The official grid comprises 19×19 lines, though the rules can be applied to any grid size; 13×13 and 9×9 are popular choices to teach beginners.[5] Once placed, a stone may not be moved to a different point.[6]

Vertically and horizontally adjacent stones of the same color form a chain (also called a string) that shares its liberties (see below) in common, cannot subsequently be subdivided, and in effect becomes a single larger stone.[7] Only stones connected to one another by the lines on the board create a chain; stones that are diagonally adjacent are not connected. Chains may be expanded by placing additional stones on adjacent intersections, and can be connected together by placing a stone on an intersection that is adjacent to two or more chains of the same color.

A vacant point adjacent to a stone is called a liberty for that stone.[8][nb 2] Stones in a chain share their liberties. A chain of stones must have at least one liberty to remain on the board. When a chain is surrounded by opposing stones so that it has no liberties, it is captured and removed from the board.

Most rule sets, except the Chinese rules, do not allow a player to place a stone in such a way that one of their own chains is left without liberties, subject to the following important exception.[9] The rule does not apply if playing the new stone results in the capture of one or more of the opponent's stones. In this case, the opponent's stones are captured first, leaving the newly played stone at least one liberty.[10] The rule just stated is said to prohibit suicide. (Since suicide is very rarely useful, making it legal does not significantly alter the nature of the game.)

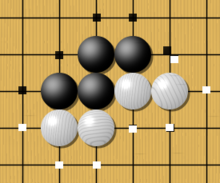

An example of a situation in which the ko rule applies

Players are not allowed to make a move that returns the game to a previous position. This rule, called the ko rule (from the Japanese 劫 kō "eon"), prevents unending repetition.[11] See the example to the right: Black has just played the stone marked 1, capturing a white stone at the intersection marked with a circle. If White were now allowed to play on the marked intersection, that move would capture the black stone marked 1 and recreate the situation before Black made the move marked 1. Allowing this could result in an unending cycle of captures by both players. The ko rule therefore prohibits White from playing at the marked intersection immediately. Instead White must play elsewhere; Black can then end the ko by filling at the marked intersection, creating a five-stone Black chain. If White wants to continue the ko (that specific repeating position), White will try to find a play elsewhere on the board that Black must answer; if Black answers, then White can retake the ko. A repetition of such exchanges is called a ko fight.[12]

While the various rule sets agree on the ko rule prohibiting returning the board to an immediately previous position, they deal in different ways with the relatively uncommon situation in which a player might recreate a past position that is further removed. See Rules of Go: Repetition for further information.

Instead of placing a stone, a player may pass. This usually occurs when they believe no useful moves remain. When both players pass consecutively, the game ends and is then scored.

Scoring rules

There are two basic scoring systems used to determine the winner at the end of a game; they almost always give the same result. Territory scoring counts the number of empty points your stones surround, together with the number of stones you captured. While it originated in China, today it is commonly associated with Japan and Korea. Area scoring counts the number of points your stones occupy and surround. It is associated with contemporary Chinese play and was probably established there during the Ming Dynasty in the 15th or 16th century.[13]

Detailed description

After both players have passed consecutively, the stones that are still on the board but unable to avoid capture, called dead stones, are removed. (When both sides have passed, skilled players will nearly always agree which stones are dead and which are alive.)

Area scoring (including Chinese): A player's score is the number of stones they have on the board, plus the number of empty intersections surrounded by that player's stones.

Territory scoring (including Japanese and Korean): In the course of the game, each player retains the stones they capture, termed prisoners. Any dead stones removed at the end of the game become prisoners. The score is the number of empty points enclosed by a player's stones, plus the number of prisoners captured by that player.[nb 3]

If there is disagreement about which stones are dead, then under area scoring rules, the players simply resume play to resolve the matter. The score is computed using the position after the next time the players pass consecutively. Under territory scoring, the rules are considerably more complex; however, in practice, players will generally play on, and, once the status of each stone has been determined, return to the position at the time the first two consecutive passes occurred and remove the dead stones. For further information, see Rules of Go.

Given that the number of stones a player has on the board is related to the number of prisoners the opponent has taken, the resulting net score (the difference between Black and White's respective scores) under both rulesets is often identical and rarely differs by more than a point.[14]

Life and death

While not actually mentioned in the rules of Go (at least in simpler rule sets, such as those of New Zealand and the US), the concept of a living group of stones is necessary for a practical understanding of the game.[15]

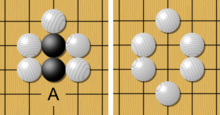

Examples of eyes

When a group of stones is mostly surrounded and has no options to connect with friendly stones elsewhere, the status of the group is either alive, dead or unsettled. A group of stones is said to be alive if it cannot be captured, even if the opponent is allowed to move first. Conversely, a group of stones is said to be dead if it cannot avoid capture, even if the owner of the group is allowed the first move. Otherwise, the group is said to be unsettled: in such a situation, the player that moves first may be able to either make it alive if he is the owner, or kill it if he is the group owner's opponent.[15]

Example of seki (mutual life)

For a group to be alive, it needs to be able to create at least two "eyes" if threatened. An eye is an empty point that is surrounded by friendly stones and where the opponent can never play due to the suicide rule. If two such eyes exist, the opponent can never capture a group of stones, because it will always have at least two liberties. One eye is not enough for life, because a point that would normally be suicide may be played upon if doing so fills the last liberty of opposing stones, thereby capturing those stones. In the "Examples of eyes" diagram, all the circled points are eyes. The two black groups in the upper corners are alive, as both have at least two eyes. The groups in the lower corners are dead, as both have only one eye. The group in the lower left may seem to have two eyes, but the surrounded empty point without a circle is not actually an eye. White can play there and take a black stone. Such a point is often called a false eye.[15]

There is a rare exception to the requirement that a group must have two eyes to be alive, a situation called seki (or mutual life). Where different coloured groups are adjacent and share liberties, the situation may reach a position when neither player wants to move first, because doing so would allow the opponent to capture; such situations therefore remain on the board.[nb 4] Sekis can occur in many ways. The simplest are: (1) each player has a group without eyes and they share two liberties, and (2) each player has a group with one eye and they share one more liberty. In the "Example of seki (mutual life)" diagram, the circled points are liberties shared by both a black and a white group. Neither player wants to play on a circled point, because doing so would allow the opponent to capture. All the other groups in this example, both black and white, are alive with at least two eyes. Sekis are unusual, but can result from an attempt by one player to invade and kill a nearly settled group of the other player.[15]

History

Origin in China

The earliest written reference to the game is generally recognized as the historical annal Zuo Zhuan[16] (c. 4th century BC),[17] referring to a historical event of 548 BC. It is also mentioned in Book XVII of the Analects of Confucius (c. 3rd century BC)[17] and in two books written by Mencius[18] (c. 3rd century BC).[17] In all of these works, the game is referred to as yì (弈). Today, in China, it is known as weiqi (simplified Chinese: 围棋; traditional Chinese: 圍棋; pinyin: wéiqí; Wade–Giles: wei ch'i), literally the "encirclement board game".

Go was originally played on a 17×17 line grid, but a 19×19 grid became standard by the time of the Tang Dynasty (618–907).[19] Legends trace the origin of the game to Chinese emperor Yao (2337–2258 BC), said to have had his counselor Shun design it for his unruly son, Danzhu to favorably influence him.[20] Other theories suggest that the game was derived from Chinese tribal warlords and generals, who used pieces of stone to map out attacking positions.[21]

In China, Go was perceived as the popular game of the aristocracy, while Xiangqi (Chinese chess) was the game of the masses. Go was considered one of the four cultivated arts of the Chinese scholar gentleman, along with calligraphy, painting and playing the musical instrument guqin.[22]

Spread to Korea and Japan

Weiqi was introduced to Korea sometime between the 5th and 7th centuries AD, and was popular among the higher classes. In Korea, the game is called baduk (hangul: 바둑), and a variant of the game called Sunjang baduk was developed by the 16th century. Sunjang baduk became the main variant played in Korea until the end of the 19th century.[23][24]

The game reached Japan in the 7th century AD —where it is called go (碁) or igo (囲碁)—the game became popular at the Japanese imperial court in the 8th century,[25] and among the general public by the 13th century.[26] In 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu re-established Japan's unified national government. In the same year, he assigned the then-best player in Japan, a Buddhist monk named Nikkai (né Kanō Yosaburo, 1559), to the post of Godokoro (Minister of Go).[27] Nikkai took the name Honinbo Sansa and founded the Honinbo Go school.[27] Several competing schools were founded soon after.[27] These officially recognized and subsidized Go schools greatly developed the level of play and introduced the dan/kyu style system of ranking players.[28] Players from the four schools (Honinbo, Yasui, Inoue and Hayashi) competed in the annual castle games, played in the presence of the shogun.[29]

Go in the West

Despite its widespread popularity in East Asia, Go has been slow to spread to the rest of the world. Although there are some mentions of the game in western literature from the 16th century forward, Go did not start to become popular in the West until the end of the 19th century, when German scientist Oskar Korschelt wrote a treatise on the game.[30] By the early 20th century, Go had spread throughout the German and Austro-Hungarian empires. In 1905, Edward Lasker learned the game while in Berlin. When he moved to New York, Lasker founded the New York Go Club together with (amongst others) Arthur Smith, who had learned of the game while touring the East and had published the book The Game of Go in 1908.[31] Lasker's book Go and Go-moku (1934) helped spread the game throughout the US,[31] and in 1935, the American Go Association was formed.(In the American Go Association, when passing, you must give the opposing player a stone as a capture). Two years later, in 1937, the German Go Association was founded.

World War II put a stop to most Go activity, but after the war, Go continued to spread.[32] For most of the 20th century, the Japan Go Association played a leading role in spreading Go outside East Asia by publishing the English-language magazine Go Review in the 1960s; establishing Go centers in the US, Europe and South America; and often sending professional teachers on tour to Western nations.[33]

In 1996, NASA astronaut Daniel Barry and Japanese astronaut Koichi Wakata became the first people to play Go in space. Both astronauts were awarded honorary dan ranks by the Nihon Ki-in.[34]

As of 2008[update], the International Go Federation has a total of 71 member countries.[35] It has been claimed that across the world 1 person in every 222 plays Go.[36]

Equipment

It is possible to play Go with a simple paper board and coins or plastic tokens for the stones. More popular midrange equipment includes cardstock, a laminated particle board, or wood boards with stones of plastic or glass. More expensive traditional materials are still used by many players. The most expensive Go sets have black stones carved from slate and white stones carved from translucent white shells.

Traditional equipment

Boards

The Go board (generally referred to by its Japanese name goban) typically measures between 45 and 48 cm (18 and 19 in) in length (from one player's side to the other) and 42 to 44 cm (17 to 17 in) in width. Chinese boards are slightly larger, as a traditional Chinese Go stone is slightly larger to match. The board is not square; there is a 15:14 ratio in length to width, because with a perfectly square board, from the player's viewing angle the perspective creates a foreshortening of the board. The added length compensates for this.[37] There are two main types of boards: a table board similar in most respects to other game boards like that used for chess, and a floor board, which is its own free-standing table and at which the players sit.

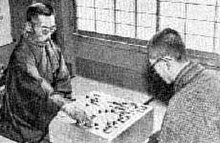

The traditional Japanese goban is between 10 and 18 cm (3.9 and 7.1 in) thick and has legs; it sits on the floor (see picture to right).[37] It is preferably made from the rare golden-tinged Kaya tree (Torreya nucifera), with the very best made from Kaya trees up to 700 years old. More recently, the related California Torreya (Torreya californica) has been prized for its light color and pale rings, as well as its less expensive and more readily available stock. The natural resources of Japan have been unable to keep up with the enormous demand for the slow-growing Kaya trees; both T. nucifera and T. californica take many hundreds of years to grow to the necessary size, and they are now extremely rare, raising the price of such equipment tremendously.[38] As Kaya trees are a protected species in Japan, they cannot be harvested until they have died. Thus, an old-growth, floor-standing Kaya goban can easily cost in excess of US$10,000 with the highest-quality examples costing more than $60,000.[39]

Other, less expensive woods often used to make quality table boards in both Chinese and Japanese dimensions include Hiba (Thujopsis dolabrata), Katsura (Cercidiphyllum japonicum), Kauri (Agathis), and Shin Kaya (various varieties of spruce, commonly from Alaska, Siberia and China's Yunnan Province).[38] So-called Shin Kaya is a potentially confusing merchant's term: shin means "new", and thus shin kaya is best translated "faux kaya", because the woods so described are biologically unrelated to Kaya.[38]

Stones

A full set of Go stones (goishi) usually contains 181 black stones and 180 white ones; a 19×19 grid has 361 points, so there are enough stones to cover the board, and Black gets the extra odd stone because that player goes first.

Traditional Japanese stones are double-convex, and made of clamshell (white) and slate (black).[40] The classic slate is nachiguro stone mined in Wakayama Prefecture and the clamshell from the Hamaguri clam; however, due to a scarcity in the Japanese supply of this clam, the stones are most often made of shells harvested from Mexico.[40] Historically, the most prized stones were made of jade, often given to the reigning emperor as a gift.[40]

In China, the game is traditionally played with single-convex stones[40] made of a composite called Yunzi. The material comes from Yunnan Province and is made by sintering a proprietary and trade-secret mixture of mineral compounds. This process dates to the Tang Dynasty and, after the knowledge was lost in the 1920s during the Chinese Civil War, was rediscovered in the 1960s by the now state-run Yunzi company. The material is praised for its colors, its pleasing sound as compared to glass or to synthetics such as melamine, and its lower cost as opposed to other materials such as slate/shell. The term "yunzi" can also refer to a single-convex stone made of any material; however, most English-language Go suppliers will specify Yunzi as a material and single-convex as a shape to avoid confusion, as stones made of Yunzi are also available in double-convex while synthetic stones can be either shape.

Traditional stones are made so that black stones are slightly larger in diameter than white; this is to compensate for the optical illusion created by contrasting colors that would make equal-sized white stones appear larger on the board than black stones.[40][nb 5]

Bowls

The bowls for the stones are shaped like a flattened sphere with a level underside.[41] The lid is loose fitting and upturned before play to receive stones captured during the game. Chinese bowls are slightly larger, and a little more rounded, a style known generally as Go Seigen; Japanese Kitani bowls tend to have a shape closer to that of the bowl of a snifter glass, such as for brandy. The bowls are usually made of turned wood. Rosewood is the traditional material for Japanese bowls, but is very expensive; wood from the Chinese jujube date tree, which has a lighter color (it is often stained) and slightly more visible grain pattern, is a common substitute for rosewood, and traditional for Go Seigen-style bowls. Other traditional materials used for making Chinese bowls include lacquered wood, ceramics, stone and woven straw or rattan. The names of the bowl shapes, Go Seigen and Kitani, pay homage to two 20th-century professional Go players by the same names, of Chinese and Japanese nationality, respectively, who are referred to as the "Fathers of modern Go".[42]

Modern and low-cost alternatives

In clubs and at tournaments, where large numbers of sets must be purchased and maintained by one organization, expensive traditional sets are not usually used. For these situations, table boards are usually used instead of floor boards, and are either made of a lower-cost wood such as spruce or bamboo, or are flexible mats made of vinyl that can be rolled up. In such cases, the stones are usually made of glass, plastic or resin (such as melamine or Bakelite) rather than slate and shell. Bowls are often made of plastic or inexpensive wood.

Common "novice" Go sets are all-inclusive kits made of particle board or plywood, with plastic or glass stones, that either fold up to enclose the stone containers or have pull-out drawers to keep stones. In relative terms, these sets are inexpensive, costing US$20–$40 depending on component quality, and thus are popular with casual Go players. Magnetic sets are also available, either as portable travel sets or in larger sizes for educational purposes.

Playing technique and etiquette

The traditional way to place a Go stone is to first take one from the bowl, gripping it between the index and middle fingers, with the middle finger on top, and then placing it directly on the desired intersection.[43] It is considered respectful towards one's opponent to place one's first stone in the upper right-hand corner.[44] It is permissible to emphasize select moves by striking the board more firmly than normal, thus producing a sharp clack.

Time control

A game of Go may be timed using a game clock. Formal time controls were introduced into the professional game during the 1920s and were controversial.[45] Adjournments and sealed moves began to be regulated in the 1930s. Go tournaments use a number of different time control systems. All common systems envisage a single main period of time for each player for the game, but they vary on the protocols for continuation (in overtime) after a player has finished that time allowance.[nb 6] The most widely used time control system is the so called byoyomi[nb 7] system. The top professional Go matches have timekeepers so that the players do not have to press their own clocks.

Two widely used variants of the byoyomi system are:[46]

- Standard byoyomi: After the main time is depleted, a player has a certain number of time periods (typically around thirty seconds). After each move, the number of full time periods that the player took (possibly zero) is subtracted. For example, if a player has three thirty-second time periods and takes thirty or more (but less than sixty) seconds to make a move, they lose one time period. With 60–89 seconds, they lose two time periods, and so on. If, however, they take less than thirty seconds, the timer simply resets without subtracting any periods. Using up the last period means that the player has lost on time.

- Canadian byoyomi: After using all of their main time, a player must make a certain number of moves within a certain period of time, such as twenty moves within five minutes.[46][nb 8] If the time period expires without the required number of stones having been played, then the player has lost on time.[nb 9]

Notation and recording games

Go games are recorded with a simple coordinate system. This is comparable to algebraic chess notation, except that Go stones do not move and thus require only one coordinate per turn. Coordinate systems include purely numerical (4-4 point), hybrid (K3), and purely alphabetical.[47] The Smart Game Format uses alphabetical coordinates internally, but most editors represent the board with hybrid coordinates as this reduces confusion. The Japanese word kifu is sometimes used to refer to a game record.

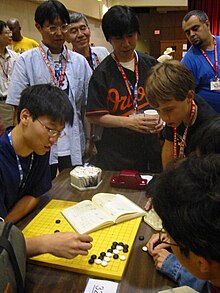

Competitive play

Ranks and ratings

In Go, rank indicates a player's skill in the game. Traditionally, ranks are measured using kyu and dan grades,[48] a system which also has been adopted by many martial arts. More recently, mathematical rating systems similar to the Elo rating system have been introduced.[49] Such rating systems often provide a mechanism for converting a rating to a kyu or dan grade.[49] Kyu grades (abbreviated k) are considered student grades and decrease as playing level increases, meaning 1st kyu is the strongest available kyu grade. Dan grades (abbreviated d) are considered master grades, and increase from 1st dan to 7th dan. First dan equals a black belt in eastern martial arts using this system. The difference among each amateur rank is one handicap stone. For example, if a 5k plays a game with a 1k, the 5k would need a handicap of four stones to even the odds. Top-level amateur players sometimes defeat professionals in tournament play.[50] Professional players have professional dan ranks (abbreviated p), these ranks are separate from amateur ranks

The rank system comprises, from the lowest to highest ranks:

| Rank Type | Range | Stage |

|---|---|---|

| Double-digit kyu | 30–20k | Beginner |

| Double-digit kyu | 19–10k | Casual player |

| Single-digit kyu | 9–1k | Intermediate/club player |

| Amateur dan | 1–7d (where 8d is special title) | Expert player |

| Professional dan | 1–9p (where 10p is special title) | Professionals |

Tournament and match rules

Tournament and match rules deal with factors that may influence the game but are not part of the actual rules of play. Such rules may differ between events. Rules that influence the game include: the setting of compensation points (komi), handicap strategies, and time control parameters. Rules that do not generally influence the game are: the tournament system, pairing strategies, and placement criteria.

Common tournament systems used in Go include the McMahon system,[51] Swiss system, league systems and the knockout system. Tournaments may combine multiple systems; many professional Go tournaments use a combination of the league and knockout systems.[52]

Tournament rules may also set the following:

- compensation points, called komi, which compensate the second player for the first move advantage of his opponent; tournaments commonly use a compensation in the range of 5–8 points,[53] generally including a half-point to prevent draws;

- compensation stones placed on the board before alternate play, allowing players of different strengths to play competitively (see Go handicap for more information); and

- superko: Although the basic ko rule described above covers more than 95% of all cycles occurring in games,[54] there are some complex situations—triple ko, eternal life,[nb 10] etc.—that are not covered by it but would allow the game to cycle indefinitely. To prevent this, the ko rule is sometimes extended to disallow the repetition of any previous position. This extension is called superko.[54]

Top players

Although the game was developed in China, the establishment of the Four Go houses by Tokugawa Ieyasu at the start of the 17th century shifted the focus of the Go world to Japan. State sponsorship, allowing players to dedicate themselves full time to study of the game, and fierce competition between individual houses resulted in a significant increase in the level of play. During this period, the best player of his generation was given the prestigious title Meijin (master) and the post of Godokoro (minister of Go). Of special note are the players who were dubbed Kisei (Go Sage). The only three players to receive this honor were Dosaku, Jowa and Shusaku, all of the house Honinbo.[42]

After the end of the Tokugawa shogunate and the Meiji Restoration period, the Go houses slowly disappeared, and in 1924, the Nihon Ki-in (Japanese Go Association) was formed. Top players from this period often played newspaper-sponsored matches of 2–10 games.[55] Of special note are Go Seigen (Chinese: Wu Qingyuan), who scored an impressive 80% in these matches,[56] and Minoru Kitani, who dominated matches in the early 1930s.[57] These two players are also recognized for their groundbreaking work on new opening theory (Shinfuseki).[58]

For much of the 20th century, Go continued to be dominated by players trained in Japan. Notable names included Eio Sakata, Rin Kaiho (born in China), Masao Kato, Koichi Kobayashi and Cho Chikun (born Cho Ch'i-hun, South Korea).[59] Top Chinese and Korean talents often moved to Japan, because the level of play there was high and funding was more lavish. One of the first Korean players to do so was Cho Namchul, who studied in the Kitani Dojo 1937–1944. After his return to Korea, the Hanguk Kiwon (Korea Baduk Association) was formed and caused the level of play in South Korea to rise significantly in the second half of the 20th century.[60] In China, the game declined during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) but quickly recovered in the last quarter of the 20th century, bringing Chinese players, such as Nie Weiping and Ma Xiaochun, on par with their Japanese and Korean counterparts.[61]

With the advent of major international titles from 1989 onward, it became possible to compare the level of players from different countries more accurately. Korean players such as Lee Chang-ho, Cho Hunhyun, Lee Sedol and Yoo Changhyuk dominated international Go and won an impressive number of titles.[62] Several Chinese players also rose to the top in international Go, most notably Ma Xiaochun, Chang Hao and Gu Li. As of 2008[update], Japan lags behind in the international Go scene.

Historically, as with most sports and games, more men than women have played Go. Special tournaments for women exist, but until recently, men and women did not compete together at the highest levels; however, the creation of new, open tournaments and the rise of strong female players, most notably Rui Naiwei, have in recent years highlighted the strength and competitiveness of emerging female players.[63]

The level in other countries has traditionally been much lower, except for some players who had preparatory professional training in Asia.[nb 11] Knowledge of the game has been scant elsewhere up until the 20th century. A famous player of the 1920s was Edward Lasker.[nb 12] It was not until the 1950s that more than a few Western players took up the game as other than a passing interest. In 1978, Manfred Wimmer became the first Westerner to receive a professional player's certificate from an Asian professional Go association.[64] In 2000, a Westerner, Michael Redmond, finally achieved the top rank awarded by an Asian Go association, 9 dan. In total, as of 2008[update], only nine non-Asian Go players have ever achieved professional status in Asian associations.

Tactics

In Go, tactics deal with immediate fighting between stones, capturing and saving stones, life, death and other issues localized to a specific part of the board. Larger issues, not limited to only part of the board, are referred to as strategy, and are covered in their own section.

Capturing tactics

There are several tactical constructs aimed at capturing stones.[65] These are among the first things a player learns after understanding the rules. Recognizing the possibility that stones can be captured using these techniques is an important step forward.

A ladder. Black cannot escape unless the ladder connects to friendly stones further down the board.

The most basic technique is the ladder.[66] To capture stones in a ladder, a player uses a constant series of capture threats—called atari—to force the opponent into a zigzag pattern as shown in the diagram to the right. Unless the pattern runs into friendly stones along the way, the stones in the ladder cannot avoid capture. Experienced players will recognize the futility of continuing the pattern and will play elsewhere. The presence of a ladder on the board does give a player the option to play a stone in the path of the ladder, thereby threatening to rescue their stones, forcing a response. Such a move is called a ladder breaker and may be a powerful strategic move. In the diagram, Black has the option of playing a ladder breaker.

A net. The chain of three black stones cannot escape in any direction.

Another technique to capture stones is the so-called net,[67] also known by its Japanese name, geta. This refers to a move that loosely surrounds some stones, preventing their escape in all directions. An example is given in the diagram to the left. It is generally better to capture stones in a net than in a ladder, because a net does not depend on the condition that there are no opposing stones in the way, nor does it allow the opponent to play a strategic ladder breaker.

A snapback. Although Black can capture the white stone by playing at the circled point, White can then snap back by playing at 1 again.

A third technique to capture stones is the snapback.[68] In a snapback, one player allows a single stone to be captured, then immediately plays on the point formerly occupied by that stone; by so doing, the player captures a larger group of their opponent's stones, in effect snapping back at those stones. An example can be seen on the right. As with the ladder, an experienced player will not play out such a sequence, recognizing the futility of capturing only to be captured back immediately.

Reading ahead

One of the most important skills required for strong tactical play is the ability to read ahead. Reading ahead includes considering available moves to play, the possible responses to each move, and the subsequent possibilities after each of those responses. Some of the strongest players of the game can read up to 40 moves ahead even in complicated positions.[69]

As explained in the scoring rules, some stone formations can never be captured and are said to be alive, while other stones may be in the position where they cannot avoid being captured and are said to be dead. Much of the practice material available to students of the game comes in the form of life and death problems, also known as tsumego.[70] In such problems, players are challenged to find the vital move sequence that will kill a group of the opponent or save a group of their own. Tsumego are considered an excellent way to train a player's ability at reading ahead,[70] and are available for all skill levels, some posing a challenge even to top players.

Ko fighting

In situations when the Ko rule applies, a ko fight may occur.[12] If the player who is prohibited from capture is of the opinion that the capture is important, because it prevents a large group of stones from being captured for instance, the player may play a ko threat.[12] This is a move elsewhere on the board that threatens to make a large profit if the opponent does not respond. If the opponent does respond to the ko threat, the situation on the board has changed, and the prohibition on capturing the ko no longer applies. Thus the player who made the ko threat may now recapture the ko. Their opponent is then in the same situation and can either play a ko threat as well, or concede the ko by simply playing elsewhere. If a player concedes the ko, either because they do not think it important or because there are no moves left that could function as a ko threat, they have lost the ko, and their opponent may connect the ko.

Instead of responding to a ko threat, a player may also choose to ignore the threat and connect the ko.[12] They thereby win the ko, but at a cost. The choice of when to respond to a threat and when to ignore it is a subtle one, which requires a player to consider many factors, including how much is gained by connecting, how much is lost by not responding, how many possible ko threats both players have remaining, what the optimal order of playing them is, and what the size—points lost or gained—of each of the remaining threats is.

Frequently, the winner of the ko fight does not connect the ko but instead captures one of the chains that constituted their opponent's side of the ko.[12] In some cases, this leads to another ko fight at a neighboring location.

Strategy

Strategy deals with global influence, interaction between distant stones, keeping the whole board in mind during local fights, and other issues that involve the overall game. It is therefore possible to allow a tactical loss when it confers a strategic advantage.

Go is not easy to play well. With each new level (rank) comes a deeper appreciation for the subtlety and nuances involved and for the insight of stronger players. The acquisition of major concepts of the game comes slowly. Novices often start by randomly placing stones on the board, as if it were a game of chance; they inevitably lose to experienced players who know how to create effective formations. An understanding of how stones connect for greater power develops, and then a few basic common opening sequences may be understood. Learning the ways of life and death helps in a fundamental way to develop one's strategic understanding of weak groups. [nb 13] It is necessary to play thousands of games before one can get close to one's ultimate potential skill level in Go. A player who both plays aggressively and can handle adversity is said to display kiai, or fighting spirit, in the game.

Familiarity with the board shows first the tactical importance of the edges, and then the efficiency of developing in the corners first, then sides, then center. The more advanced beginner understands that territory and influence are somewhat interchangeable—but there needs to be a balance. This intricate struggle of power and control makes the game highly dynamic.

Basic concepts

Basic strategic aspects include the following:

- Connection: Keeping one's own stones connected means that fewer groups need defense.

- Cut: Keeping opposing stones disconnected means that the opponent needs to defend more groups.

- Life: This is the ability of stones to permanently avoid capture. The simplest and usual way is for the group to surround two eyes (separate empty areas), so that filling one eye will not kill the group; as a result, any such move is suicidal and the group cannot be captured. The fundamental strategy of Go is to create groups with life while preventing one's opponent from doing the same.

- Mutual life (seki): A situation in which neither player can play to a particular point without then allowing the other player to play at another point to capture. The most common example is that of adjacent groups that share their last few liberties. If either player plays in the shared liberties, they reduce their own group to a single liberty (putting themselves in atari), allowing their opponent to capture it on the next move.

- Death: The absence of life coupled with the inability to create it, resulting in the eventual removal of a group.

- Invasion: Setting up a new living position inside an area where the opponent has greater influence, as a means of balancing territory.

- Reduction: Placing a stone far enough into the opponent's area of influence to reduce the amount of territory they will eventually get, but not so far in that it can be cut off from friendly stones outside.

- Sente: A play that forces one's opponent to respond (gote), such as placing an opponent's group in atari (immediate danger of capture). A player who can regularly play sente has the initiative, as in chess, and can control the flow of the game.

- Sacrifice: Allowing a group to die in order to carry out a play, or plan, in a more important area.

The strategy involved can become very abstract and complex. High-level players spend years improving their understanding of strategy, and a novice may play many hundreds of games against opponents before being able to win regularly.

Opening strategy

In the opening of the game, players will usually play in the corners of the board first, as the presence of two edges make it easier for them to surround territory and establish their stones.[72] After the corners, focus moves to the sides, where there is still one edge to support a player's stones. Opening moves are generally on the third and fourth line from the edge, with occasional moves on the second and fifth lines. In general, stones on the third line offer stability and are good defensive moves, whereas stones on the fourth line influence more of the board and are good attacking moves.

In the opening, players often play established sequences called joseki, which are locally balanced exchanges;[73] however, the joseki chosen should also produce a satisfactory result on a global scale. It is generally advisable to keep a balance between territory and influence. Which of these gets precedence is often a matter of individual taste.

Phases of the game

While the opening moves in a game have a distinct set of aims, they usually make up only 10% to at most 20% of the game. In other words, in a game of 250 moves, there may be around 30 or so opening moves, with limited "fighting". At the end of such a game, there will also be perhaps 100 moves that are counted as "endgame", in which territories are finished off definitively and all issues on capturing stones become clear. The middle phase of the game is the most combative, and usually lasts for more than 100 moves. During the middlegame, or just "the fighting", the players invade each others' frameworks, and attack weak groups, formations that lack the necessary two eyes for viability. Such groups must run away, i.e. expand to avoid enclosure, giving a dynamic feeling to the struggle. It is quite possible that one player will succeed in capturing a large weak group of the opponent's, which will often prove decisive and end the game by a resignation. But matters may be more complex yet, with major trade-offs, apparently dead groups reviving, and skillful play to attack in such a way as to construct territories rather than to kill.

The end of the middlegame and transition to the endgame is marked by a few features. The game breaks up into areas that do not affect each other (with a caveat about ko fights), where before the central area of the board related to all parts of it. No large weak groups are still in serious danger. Moves can reasonably be attributed some definite value, such as 20 points or fewer, rather than simply being necessary to compete. Both players set limited objectives in their plans, in making or destroying territory, capturing or saving stones. These changing aspects of the game usually occur at much the same time, for strong players. In brief, the middlegame switches into the endgame when the concepts of strategy and influence need reassessment in terms of concrete final results on the board.

Computers and Go

Nature of the game

In combinatorial game theory terms, Go is a zero sum, perfect-information, partisan, deterministic strategy game, putting it in the same class as chess, checkers (draughts) and Reversi (Othello); however it differs from these in its game play. Although the rules are simple, the practical strategy is extremely complex.

The game emphasizes the importance of balance on multiple levels and has internal tensions. To secure an area of the board, it is good to play moves close together; however, to cover the largest area, one needs to spread out, perhaps leaving weaknesses that can be exploited. Playing too low (close to the edge) secures insufficient territory and influence, yet playing too high (far from the edge) allows the opponent to invade.

It has been claimed that Go is the most complex game in the world due to its vast number of variations in individual games.[74] Its large board and lack of restrictions allow great scope in strategy and expression of players' individuality. Decisions in one part of the board may be influenced by an apparently unrelated situation in a distant part of the board. Plays made early in the game can shape the nature of conflict a hundred moves later.

The game complexity of Go is such that describing even elementary strategy fills many introductory books. In fact, numerical estimates show that the number of possible games of Go far exceeds the number of atoms in the known universe.[nb 14]

Software players

Go poses a daunting challenge to computer programmers.[75] While the strongest computer chess programs can defeat the best human players (for example, the Deep Fritz program, running on a laptop, beat reigning world champion Vladimir Kramnik without losing a single game in 2006), the best Go programs only manage to reach an intermediate amateur level. On the small 9×9 board, the computer fares better, and some programs now win a fraction of their 9x9 games against professional players . Human players generally achieve an intermediate amateur level by studying and playing regularly for a few years. Many in the field of artificial intelligence consider Go to require more elements that mimic human thought than chess.[76] However, this does not take into account chess aesthetics which - unlike typical chess playing technology - has only relatively recently become amenable to scientific investigation and computation.

The reasons why computer programs do not play Go well are attributed to many qualities of the game,[77] including:

- The number of spaces on the board is much larger (over five times the spaces on a chess board—361 vs. 64). On most turns there are many more possible moves in Go than in chess. Throughout most of the game, the number of legal moves stays at around 150–250 per turn, and rarely goes below 50 (in chess, the average number of moves is 37).[78] Because an exhaustive computer program for Go must calculate and compare every possible legal move in each ply (player turn), its ability to calculate the best plays is sharply reduced when there are a large number of possible moves. Most computer game algorithms, such as those for chess, compute several moves in advance. Given an average of 200 available moves through most of the game, for a computer to calculate its next move by exhaustively anticipating the next four moves of each possible play (two of its own and two of its opponent's), it would have to consider more than 320 billion (3.2×1011) possible combinations. To exhaustively calculate the next eight moves, would require computing 512 quintillion (5.12×1020) possible combinations. As of June 2008[update], the most powerful supercomputer in the world, IBM's "Roadrunner" distributed cluster, can sustain 1.02 petaflops.[79][80][81] At this rate, even given an exceedingly low estimate of 10 flops required to assess the value of one play of a stone, Roadrunner would require 138 hours, more than five days, to assess all possible combinations of the next eight moves in order to make a single play.

- Unlike chess and Reversi, the placement of a single stone in the initial phase can affect the play of the game hundreds of moves later. For a computer to have a real advantage over a human, it would have to predict this influence, and from the example above, it would be completely unworkable to attempt to exhaustively analyze the next hundred moves to predict what a stone's placement will do.

- In capture-based games (such as chess), a position can often be evaluated relatively easily, such as by calculating who has a material advantage or more active pieces.[nb 15] In Go, there is often no easy way to evaluate a position.[75][82] The number of stones on the board (material advantage) is only a weak indicator of the strength of a position, and a territorial advantage (more empty points surrounded) for one player might be compensated by the opponent's strong positions and influence all over the board.

As an illustration, the greatest handicap normally given to a weaker opponent is 9 stones. It was not until August 2008 that a computer was able to win a game against a professional level player at this handicap. It was the Mogo program which scored said first victory in an exhibition game played during the US Go Congress.[83][84]

Software assistance

Beyond programs that play Go, there is an abundance of software available to support players of the game. This includes programs that can be used to view or edit game records and diagrams, programs that allow the user to search for patterns in the games of strong players, and programs that allow users to play against each other over the Internet.

There are several file formats used to store game records, the most popular of which is SGF, short for Smart Game Format. Programs used for editing game records allow the user to record not only the moves, but also variations, commentary and further information on the game.[nb 16]

Electronic databases can be used to study life and death situations, joseki, fuseki and games by a particular player. Programs are available that give players pattern searching options, which allow players to research positions by searching for high-level games in which similar situations occur. Such software generally lists common follow-up moves that have been played by professionals and gives statistics on win/loss ratio in opening situations.

Internet-based Go servers allow access to competition with players all over the world.[nb 17] Such servers also allow easy access to professional teaching, with both teaching games and interactive game review being possible.[nb 18]

In culture and science

Literature, television, and film

Apart from technical literature and study material, Go and its strategies have been the subject of several works of fiction, such as The Master of Go by Nobel prize-winning author Yasunari Kawabata[nb 19] and The Girl Who Played Go by Shan Sa. Other books have used Go as a theme or minor plot device. For example, the 1979 novel Shibumi by Trevanian centers around the game and uses Go metaphors.[85] Go, referred to as Weiqi, features prominently in the 1986 Eric Van Lustbader novel Jian.

Similarly, Go has been used as a subject or plot device in film, such as π, A Beautiful Mind and Tron Legacy. Also in The Go Master, a biopic of Go professional Go Seigen.[86][nb 20] In King Hu's wuxia film The Valiant Ones, the characters are color-coded as go pieces (black or other dark shades for the Chinese, white for the Japanese invaders), go boards and stones are used by the characters to keep track of soldiers prior to battle, and the battles themselves are structured like a game of go.[87] Go is used as a device for criminal profiling in the pilot episode of Criminal Minds, "Extreme Aggressor".

Of particular note is the manga (Japanese comic book) and anime series Hikaru no Go, released in Japan in 1998, which had a large impact in popularizing Go among young players, both in Japan and—as translations were released—abroad.[88][89]

Also note that video game company Atari was named after Go. As Atari's founder Nolan Bushnell was quoted as saying: "In Go, when you are about to capture an opponent's piece, you politely warn them 'Atari'. I felt that was a good aggressive name for a company."

Psychology

A 2004 review of literature by Gobet, de Voogt & Retschitzki[90] shows that relatively little scientific research has been carried out on the psychology of Go, compared with other traditional board games such as chess and Mancala. Computer Go research has shown that given the large search tree, knowledge and pattern recognition are more important in Go than in other strategy games, such as chess.[90] A study of the effects of age on Go-playing[91] has shown that mental decline is milder with strong players than with weaker players. According to the review of Gobet and colleagues, the pattern of brain activity observed with techniques such as PET and fMRI does not show large differences between Go and chess. On the other hand, a study by Xiangchuan Chen et al.[92] showed greater activation in the right hemisphere among Go players than among chess players. There is some evidence to suggest a correlation between playing board games and reduced risk of Alzheimer's disease and dementia.[93]

See also

{{{inline}}}

- Go at the 2010 Asian Games

- Go opening strategy

- Go proverbs

- Go variants and Games played with Go equipment

- List of Go organizations

- List of professional Go tournaments

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ The full Japanese name igo is derived from its Chinese name weiqi, which roughly translates as "board game of surrounding", see Etymology Of Go at Sensei's Library for more information. To differentiate it from the common English verb to go, it is sometimes capitalized or, in events sponsored by the Ing Foundation, spelled goe.

- ^ Compare "liberty", a small local government unit in medieval England – the "local area under control".

- ^ Exceptionally, in Japanese and Korean rules, empty points, even those surrounded by stones of a single colour, may count as neutral territory if some of them are alive by seki. See the section on "Life and Death" for seki.

- ^ In game theoretical terms, seki positions are an example of a Nash equilibrium.

- ^ See Overshoot in Western typography for similar subtle adjustment to create a uniform appearance.

- ^ Roughly, one has the time to play the game and then a little time to finish it off. Time-wasting tactics are possible in Go, so that sudden death systems, in which time runs out at a predetermined point however many plays are in the game, are relatively unpopular (in the West).

- ^ Literally in Japanese byōyomi means 'reading of seconds'.

- ^ Typically, players stop the clock, and the player in overtime sets his/her clock for the desired interval, counts out the required number of stones and sets the remaining stones out of reach, so as not to become confused. If twenty moves are made in time, the timer is reset to five minutes again.

- ^ In other words, Canadian byoyomi is essentially a standard chess-style time control, based on N moves in a time period T, imposed after a main period is used up. It is possible to decrease T, or increase N, as each overtime period expires; but systems with constant T and N, for example 20 plays in 5 minutes, are widely used.

- ^ A full explanation of the eternal life position can be found on Sensei's Library, it also appears in the official text for Japanese Rules, see translation.

- ^ Kaku Takagawa toured Europe around 1970, and reported (Go Review) a general standard of amateur 4 dan. This is a good amateur level but no more than might be found in ordinary Asian clubs. Published current European ratings would suggest around 100 players stronger than that, with very few European 7 dans.

- ^ European Go has been documented by Franco Pratesi, Eurogo (Florence 2003) in three volumes, up to 1920, 1920–1950, and 1950 and later.

- ^ Whether or not a group is weak or strong refers to the ease with which it can be killed or made to live. See this article by Benjamin Teuber, amateur 6 dan, for some views on how important this is felt to be.

- ^ The number of board positions is at most 3361 (about 10172) since each position can be white, black, or vacant. There are at least 361! games (about 10768) since every permutation of the board positions corresponds to a game. See Go and mathematics for more details, which includes much larger estimates.

- ^ While chess position evaluation is simpler than Go position evaluation, it is still more complicated than simply calculating material advantage or piece activity; pawn structure and king safety matter, as do the possibilities in further play. The complexity of the algorithm differs per engine.

- ^ Lists of such programs may be found at Sensei's Library or GoBase.

- ^ Lists of Go servers are kept at Sensei's Library and the AGA website

- ^ The British Go Association provides a list of teaching services

- ^ A list of books can be found at Sensei's Library

- ^ A list of films can de found at the EGF Internet Go Filmography

Citations

- ^ Min. age suggestion (under "Product Description")

- ^ Osdir.com

- ^ British Go Association, Comparison of some go rules, retrieved 2007-12-20

- ^ NRICH Team, Going First, University of Cambridge, retrieved 2007-06-16

- ^ Kim 1994 pp. 3–4

- ^ How to place Go stones, Nihon Kiin, retrieved 2007-03-04

- ^ Matthews, Charles, Behind the Rules of Go, University of Cambridge, retrieved 2008-06-09

- ^ Kim 1994 p. 12

- ^ Kim 1994 p. 28

- ^ Kim 1994 p. 30

- ^ Kim 1994 pp 48–49

- ^ a b c d e Kim 1994 pp. 144–147

- ^ Fairbairn, John, "The Rules Debate", New in Go, Games of Go on Disc, retrieved 2007-11-27

{{citation}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Hansen, Fred, Demonstration of the Relationship of Area and Territory Scoring, American Go Association, retrieved 2008-06-16

- ^ a b c d Matthews 2002

- ^ Potter 1985; Fairbairn 1995

- ^ a b c Brooks 2007

- ^ Potter 1984; Fairbairn 1995

- ^ Fairbairn 1995

- ^ Yang, Lihui (2005). Handbook of Chinese mythology. ABC-CLIO Ltd. p. 228. ISBN 978-1576078068.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Masayoshi 2005; Lasker 1934

- ^ Pickard 1989

- ^ History of Korean baduk, Korean Baduk Association, retrieved 2008-11-13

- ^ Fairbairn 2000

- ^ History of Go in Japan: part 2, Nihon Kiin, retrieved 2007-11-02

- ^ History of Go in Japan: part 3, Nihon Kiin, retrieved 2007-11-02

- ^ a b c GoGoD (Fairbairn & Hall) (2007), "Timeline 1600–1867", History and Timelines

- ^ GoGoD (Fairbairn & Hall) (2007), "Honinbo Dosaku", Articles on Famous Players

- ^ GoGoD (Fairbairn & Hall) (2007), "Castle Games 1626–1863", History and Timelines

- ^ Pinckard, William (1992), History and Philosophy of Go in Bozulich, 2001 pp. 23–25

- ^ a b AGA 1995 Historical Book, American Go Association, retrieved 2008-06-11

- ^ Bozulich, Richard, The Magic of Go - 40. Go in Europe, Yomiuri Shimbun, retrieved 2008-06-16

- ^ British Go Association, Pro Go Player visits to UK & Ireland (since 1964), retrieved 2007-11-17

- ^ Peng & Hall 1996

- ^ International Go Federation, IGF members, retrieved 2008-05-08

- ^ John Fairbairn, Go Census, retrieved 2008-06-20

- ^ a b Fairbairn 1992 pp. 142–143

- ^ a b c Fairbairn 1992 pp. 143–149

- ^ Kiseido clearance sale lists the regular price for a Shihomasa Kaya Go Board with legs (20.4 cm or 8.0 in thick) as $60,000+

- ^ a b c d e Fairbairn 1992 pp. 150–153

- ^ Fairbairn 1992 pp. 153–155

- ^ a b Fairbairn, John, Jowa - Sage or Scoundrel, retrieved 2008-06-11

- ^ A stylish way to play your stones, Nihon Ki-in, retrieved 2007-02-24

- ^ Sensei's Library: Playing the first move in the upper right corner

- ^ Bozulich 2001 pp. 92–93

- ^ a b EGF General Tournament Rules, European Go Federation, retrieved 2008-06-11

- ^ Go FAQ

- ^ Go. The World's Most Fascinating Game, Tokyo, Japan: Nihon Kiin, 1973, p. 188

- ^ a b Cieply, Ales, EGF Official Ratings, European Go Federation (EGF), retrieved 2009-11-06

- ^ EGF Tournament Database, Association for Go in Italy (AGI), retrieved 2008-06-19

- ^ The McMahon system in a nutshell, British Go Association, archived from the original on 2008-05-18, retrieved 2008-06-11

- ^ GoGoD (Fairbairn & Hall) (2007), A quick guide to pro tournaments

- ^ GoGoD (Fairbairn & Hall) (2007), "History of Komi", History and Timelines

- ^ a b Jasiek, Robert (2001), Ko Rules, retrieved 2007-11-30

- ^ Fairbairn, John, History of Newspaper Go, retrieved 2007-06-14

- ^ Go Seigen: Match Player, GoBase.org, retrieved June 14, 2007

- ^ Fairbairn, John, Kitani's Streak, retrieved 2007-06-14

- ^ Fairbairn, John, Kubomatsu's central thesis, retrieved 2008-01-17

- ^ List of Japanese titles, prizemoney and winners, GoBase.org, retrieved 2008-06-11

- ^ Kim, Janice, KBA Founder Cho Nam Chul passes, American Go Association, retrieved 2008-06-11

- ^ Matthews, Charles, Weiqi in Chinese Culture, retrieved 2007-06-04

- ^ List of International titles, prizemoney and winners, GoBase.org, retrieved 2008-06-11

- ^ Shotwell, Peter (2003), Go! More Than a Game, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 0-8048-3475-X

- ^ Wimmer, Kerwin, Make Professional Shodan, British Go Association, retrieved 2008-06-11

- ^ Kim 1994 pp. 80–98

- ^ Kim 1994 pp. 88–90

- ^ Kim 1994 pp. 91–92

- ^ Kim 1994 pp. 93–94

- ^ Nakayama, Noriyuki (1984), "Memories of Kitani", The Treasure Chest Enigma, Slate & Shell, pp. 16–19, ISBN 1-932001-27-1

- ^ a b van Zeijst, Rob, Whenever a player asks a top professional…, Yomiuri Shimbun, retrieved 2008-06-09

- ^ http://www.go4go.net/v2/modules/collection/sgfview.php?id=1812

- ^ Otake, Hideo (2002), Opening Theory Made Easy, Kiseido Publishing Company, ISBN 490657436X

- ^ Ishida, Yoshio (1977), Dictionary of Basic Joseki, Kiseido Publishing Company

- ^ Top Ten Reasons to Play Go, American Go Association, retrieved 2008-06-11

- ^ a b Stern, David (2008-02-01), "Modelling Uncertainty in the Game of Go" (PDF), University of Cambridge, retrieved 2008-12-04

- ^ Johnson, George (1997-07-29), "To Test a Powerful Computer, Play an Ancient Game", The New York Times, retrieved 2008-06-16

- ^ Overview of Computer Go, Intelligent Go Foundation, archived from the original on 2008-05-31, retrieved 2008-06-16

- ^ Keene, Raymond; Levy, David (1991), How to beat your chess computer, Batsford Books, p. 85

- ^ Sharon Gaudin (2008-06-09). "IBM's Roadrunner smashes 4-minute mile of supercomputing". Computerworld. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- ^ "Military supercomputer sets record". CNET News.com.

- ^ "Supercomputer sets petaflop pace". BBC. 2008-06-09. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ^ Fellows, Christopher (2006-00-00), "Exploring GnuGo's Evaluation Function with SVM" (PDF), Cornell University, retrieved 2008-12-19

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Supercomputer with innovative software beats Go Professional". Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- ^ "AGA News: Kim Prevails Again In Man Vs Machine Rematch". Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ McDonald, Brian (2002) [1995], "Shibumi", in Shotwell, Peter (ed.), Go in Western Literature (PDF), American Go Association, pp. 5–6, retrieved 2008-06-16

- ^ Scott, A.O. (March 14, 2007), "A Prodigy's Life Is Played Out In a Japanese Game of Skill", The New York Times, retrieved 2008-06-16

- ^ Ng Ho (1998). "King Hu and the Aesthetics of Space". In Teo, Stephen (ed.). Transcending the Times:King Hu & Eileen Chan. Hong Kong International Film Festival. Hong Kong: Provisional Urban Council of Hong Kong. p. 45.

- ^ Shimatsuka, Yoko, Do Not Pass Go, Asiaweek, archived from the original on 2007-06-10, retrieved 2007-03-26

- ^ Scanlon, Charles (Thursday, 1 August 2002, 03:35 GMT 04:35 UK). "Young Japanese go for Go". World News. BBC. Retrieved 2009-05-21.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Gobet, F; de Voogt, A. J; Retschitzki, J (2004), Moves in Mind: The Psychology of Board Games, Hove, UK: Psychology Press, ISBN 1841693367

- ^ Masunaga, H; Horn, J. (2001), "Expertise and age-related changes in components of intelligence", Psychology and Aging, 16 (16): 293–311, doi:10.1037/0882-7974.16.2.293

- ^ Chen; et al. (2003), "A functional MRI study of high-level cognition II. The game of GO", Science Direct - Cognitive Brain Research, 16: 32, doi:10.1016/S0926-6410(02)00206-9, retrieved 2008-06-16

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Verghese; Lipton, RB; Katz, MJ; Hall, CB; Derby, CA; Kuslansky, G; Ambrose, AF; Sliwinski, M; Buschke, H; et al. (2003), "Leisure Activities and the Risk of Dementia in the Elderly", New England Journal of Medicine, 348 (25): 2508, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022252, PMID 12815136

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)

References

- Bozulich, Richard (2001), The Go Player's Almanac (2nd ed.), Kiseido Publishing Company, ISBN 4-906574-40-8

- Brooks, E Bruce (2007), Warring States Project Chronology #2, retrieved 2007-11-30

- Fairbairn, John (1992), A Survey of the best in Go Equipment in Bozulich 2001—pp. 142–155

- Fairbairn, John (1995), Go in Ancient China, retrieved 2007-11-02

- Fairbairn, John (2000), History of Go in Korea, retrieved 2007-11-06

- Fairbairn, John; Hall, T Mark (2007), The GoGoD Encyclopaedia, Games of Go on Disc

- Kim, Janice; Jeong, Soo-hyun (1994), Learn to Play Go, Good Move Press, ISBN 0-9644796-1-3

- Lasker, Edward (1960) [1934], Go and Go-Moku, Courier Dover Publications, ISBN 0486206130

- Masayoshi, Shirakawa (2005), A Journey In Search of the Origins of Go, Yutopian Enterprises, ISBN 1889554987

- Matthews, Charles (2002), Sufficient but Not Necessary: Two Eyes and Seki in Go, University of Cambridge, retrieved 2007-12-31

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Peng, Mike; Hall, Mark (1996), "One Giant Leap For Go" (PDF), Svenks Go Tidning, 96 (2): 7–8, retrieved 2007-11-12

- Pinckard, William (1989), "The Four Accomplishments", in Richard Bozulich (ed.), Japanese Prints and the World of Go, ISBN 9784906574308, retrieved 2007-11-02

{{citation}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Potter, Donald L. (1984), "Go in the Classics", Go World (37), Tokyo: Ishi Press: 16–18, retrieved 2007-11-02

- Potter, Donald L. (1985), "Go in the Classics (ii): the Tso-chuan", Go World (42), Tokyo: Ishi Press: 19–21, retrieved 2007-11-02

Further reading

Introductory books:

- Bradley, Milton N. Go for Kids, Yutopian Enterprises, Santa Monica, 2001 ISBN 978-1-889554-74-7.

- Cho, Chikun. Go: A Complete Introduction to the Game, Kiseido Publishers, Tokyo, 1997, ISBN 978-4-906574-50-6.

- Cobb, William. The Book of Go, Sterling Publishers, 2002, ISBN 978-0-8069-2729-9.

- Iwamoto, Kaoru. Go for Beginners, Pantheon, New York, 1977, ISBN 978-0-394-73331-9.

- Kim, Janice, and Jeong Soo-hyun. Learn to Play Go series, five volumes: Good Move Press, Sheboygan, Wisconsin, second edition, 1997. ISBN 0-9644796-1-3.

- Matthews, Charles. Teach Yourself Go, McGraw-Hill, 2004, ISBN 978-0-07-142977-1.

- Shotwell, Peter. Go! More than a Game, Tuttle Publishing, Boston, 2003. ISBN 0-8048-3475-X.

Historical interest:

- Boorman, Scott A. (1969), The Protracted Game: A Wei Ch'i Interpretation of Maoist Revolutionary Strategy, New York, NY: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195014938

- De Havilland, Augustus Walter (1910), The ABC of Go: The National War Game of Japan, Yokohama, Kelly & Walsh, OCLC 4800147

- Korschelt, Oscar (1966), The Theory and Practice of Go, C.E. Tuttle Co, ISBN 9780804805728

- Smith, Arthur (1956), The Game of Go: The National Game of Japan, C.E. Tuttle Co, OCLC 912228

External links

- International Go Federation (IGF), at intergofed.org

- European Go Federation (EGF), at eurogofed.org

- American Go Association (AGA), at usgo.org

- The Nihon Ki-in (Japan Go Association), at nihonkiin.or.jp

- Go Bibliography, comprehensive bibliography - reviews, cover images, details, at gobooks.nemir.org

- Go in Print, list and reviews of English Go books, at usgo.org

- Go Servers, list of servers for playing on-line at Sensei's Library, at senseis.xmp.net

- Goproblems.com, open database of interactive Go problems, at goproblems.com

Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA