Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force: Difference between revisions

m →Capabilities and recent developments: replaced: an Japanese → a Japanese using AWB |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

|unit_name= <big>Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force</big><br /><big>(JMSDF)</big><br />{{lang|ja|海上自衛隊}}<br /><small>''(Kaijō Jieitai)''</small> |

|unit_name= <big>Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force</big><br /><big>(JMSDF)</big><br />{{lang|ja|海上自衛隊}}<br /><small>''(Kaijō Jieitai)''</small> |

||

|image=[[File:Naval Ensign of Japan.svg|border|250px]] |

|image=[[File:Naval Ensign of Japan.svg|border|250px]] |

||

|caption= [[Rising Sun Flag |

|caption= [[Rising Sun Flag]] |

||

|start_date=1952 |

|start_date=1952 |

||

|country= |

|country= |

||

Revision as of 07:09, 24 June 2013

| Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) 海上自衛隊 (Kaijō Jieitai) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Founded | 1952 |

| Allegiance | |

| Type | Navy |

| Role | Defend Japanese territorial waters and shipping lines. |

| Size | 45,800 personnel 134 active ships[1][2] 339 aircraft |

| Garrison/HQ | Yokosuka, Japan |

The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (海上自衛隊, Kaijō Jieitai), or JMSDF, is the naval branch of the Japan Self-Defense Forces, tasked with the naval defense of Japan. It was formed following the dissolution of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) after World War II.[3] The JMSDF has a large fleet and its main tasks are to maintain control of the nation's sea lanes and to patrol territorial waters. It has also stepped up its participation in UN-led peacekeeping operations (PKOs) and Maritime Interdiction Operations (MIOs).

History

| Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force 日本国 海上自衛隊 (Kaijō Jieitai) |

|---|

|

| Components |

| History |

| Ships |

Origin

Japan has a long history of naval interaction with the Asian continent, involving the transportation of troops, starting at least with the beginning of the Kofun period in the 3rd century. Following the attempts at Mongol invasions of Japan by Kublai Khan in 1274 and 1281, Japanese wakō became very active in plundering the coast of the Chinese Empire.

Japan undertook major naval building efforts in the 16th century, during the Warring States period, when feudal rulers vying for supremacy built vast coastal navies of several hundred ships. Around that time, Japan may have developed one of the world's first ironclad warships, when Oda Nobunaga (a Japanese daimyo) had six iron-covered Oatakebune made in 1576.[4][5]

In 1588, Toyotomi Hideyoshi issued a ban on Wakō piracy; the pirates then became vassals of Hideyoshi and comprised the naval force used in the Japanese invasion of Korea.

Japan built her first large ocean-going warships in the beginning of the 17th century, following contact with European countries during the Nanban trade period. In 1613, the Daimyo of Sendai, in agreement with the Tokugawa Bakufu, built the Date Maru. This 500 ton galleon-type ship transported the Japanese embassy of Hasekura Tsunenaga to the Americas and Europe. From 1604 onwards, about 350 Red seal ships, usually armed and incorporating European technology, were also commissioned by the Bakufu, mainly for Southeast Asian trade.

Imperial Japanese Navy

From 1868, the restored Meiji Emperor continued with reforms to industrialize and militarize Japan to prevent the United States and European powers from overwhelming it. On 17 January 1868, the Ministry of Military Affairs was established, with Iwakura Tomomi, Shimazu Tadayoshi and Prince Komatsu-no-miya Akihito as the First Secretaries.

On 26 March 1868, the first Naval Review was held in Japan (in Osaka Bay), with 6 ships from the private domainal navies of Saga, Chōshū, Satsuma, Kurume, Kumamoto and Hiroshima participating. The total tonnage of these ships was 2252 tons, far smaller than the tonnage of the single foreign vessel (from the French Navy) that also participated. In July 1869, the Imperial Japanese Navy was formally established, two months after the last military engagement of the Boshin War - the private navies of the Japanese nobles were abolished and their 11 ships were added to the 7 surviving vessels of the defunct Tokugawa bakufu navy, including the Kankō Maru, Japan's first steam warship.[6] This formed the core of the new Imperial Japanese Navy.

An 1872 edict officially separated the Japanese Navy from the Japanese Army. Politicians like Enomoto Takeaki set out to use the Navy to expand to the islands south of Japan in similar fashion to the Army's northern and western expansion. The Navy sought to upgrade its fleet to a blue water navy and used cruises to expand the Japanese consciousness on the southern islands. Enomoto's policies helped the Navy expand and incorporate many different islands into the Japanese Empire, including Iwo Jima in 1889. The navy continued to expand and incorporate political influence throughout the early twentieth century.[7]

Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force

Following Japan's defeat in World War II, the Imperial Japanese Navy was dissolved by the Potsdam Declaration acceptance. Ships were disarmed, and some of them, such as battleship Nagato, were taken by the Allied Powers as reparation. The remaining ships were used for repatriation of the Japanese soldiers from abroad and also for minesweeping in the area around Japan. The minesweeping fleet was eventually transferred to the newly formed Maritime Safety Agency, which helped maintain the resources and expertise of the navy.

Japan's 1947 Constitution was drawn up after the conclusion of the war, Article 9 specifying that "The Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as a means of settling international disputes." The prevalent view in Japan is that this article allows for military forces to be kept for the purposes of self-defense. Due to Cold War pressures, the United States was also happy for Japan to provide part of its own defense, rather than have it fully rely on American forces.

In 1952, the Coastal Safety Force was formed within the Maritime Safety Agency, incorporating the minesweeping fleet and other military vessels, mainly destroyers, given by the United States. In 1954, the Coastal Safety Force was separated, and the JMSDF was formally created as the naval branch of the Japanese Self-Defense Force (JSDF), following the passage of the 1954 Self-Defense Forces Law.

The first ships in the JMSDF were former US Navy destroyers, transferred to Japanese control in 1954. In 1956, the JMSDF received its first domestically produced destroyer since World War II, the Harukaze. Due to the Cold War threat posed by the Soviet Navy's sizable and powerful submarine fleet, the JMSDF was primarily tasked with an anti-submarine role.

Post Cold War

Following the end of the Cold War, the role of the JMSDF has vastly changed. In 1991, after much international pressure, the JMSDF dispatched minesweepers to the Persian Gulf in the aftermath of the Gulf War to clear mines sown by Saddam Hussein's defending forces;[8] and starting with a mission to Cambodia in 1993 when JSDF personnel were supported by the JDS Towada,[8] it has been active in a number of UN-led peace keeping operations throughout Asia. In 1993, it commissioned its first Aegis-equipped destroyer, the DD173 Kongō. It has also been active in joint naval exercises with other countries, such as the United States. The JMSDF has dispatched a number of its destroyers on a rotating schedule to the Indian Ocean in an escort role for allied vessels as part of the US-led Operation Enduring Freedom.

With an increase in tensions with North Korea following the 1993 test of the Nodong-1 missile and the 1998 test of the Taepodong-1 missile over northern Japan, the JMSDF has stepped up its role in air defense. A ship-based anti-ballistic missile system was successfully test-fired on 18 December 2007 and has been installed on Japan's Aegis-class destroyers. The JMSDF, along with the Japan Coast Guard, has also been active in preventing North Korean infiltrators from reaching Japan and in December 2001, engaged and sank a North Korean spyship.

Today

Capabilities and recent developments

The JMSDF has an official strength of 46,000 personnel, but presently numbers around 45,500 active personnel.

Japan has the seventh largest Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in the world,[9] and the JMSDF is responsible for protecting this large area. As an island nation, dependent on maritime trade for the majority of its resources, including food and raw materials, maritime operations are a very important aspect of Japanese defense policy.

The JMSDF is known in particular for its antisubmarine warfare and minesweeping capabilities. Defense planners believe the most effective approach to combating hostile submarines entails mobilizing all available weapons, including surface combatants, submarines, patrol planes, and helicopters. Historically the Japan Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF) has been relied on to provide air cover at sea, a role that is subordinate to the JASDF's primary mission of air defense of the home islands. Extended patrols over sea lanes are beyond the JASDF's current capabilities.

The Japanese fleet's capacity to provide ship-based antiaircraft warfare protection is limited by the absence of aircraft carriers, though its destroyers and frigates equipped with the Aegis combat system provide a formidable capability in antiaircraft and antimissile warfare. The fleet is also short of long-range underway replenishment ships and generally deficient in all areas of logistic support. These weaknesses seriously compromise the ability of the JMSDF to fulfill its mission and operate independently of the U.S. Air Force and the U.S. 7th Fleet. However, these capabilities are force multipliers, allowing force projection of Japan's sizable destroyer and frigate force far from home waters, and acquiring them is contentious considering Japan's "passive" defense policy.

In August 2003, a new "helicopter destroyer" class was ordered, the Hyūga class helicopter destroyer. The size and features of the ship, including a full-length flight deck, will result in it being classified as either an amphibious assault ship or a helicopter carrier by Lloyd's Register — similar to the HMS Ocean (L12). It has been widely argued about whether an aircraft carrier of any kind would be technically prohibited by Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution, since aircraft carriers are generally considered offensive weapons. In a Japanese Diet budget session in April 1988, the chief of the Japanese Defense Agency, Tsutomu Kawara, said, "The Self-Defense Forces are not allowed to possess ICBMs (intercontinental ballistic missiles), strategic bombers, or attack aircraft carriers." [10]

Historically, up through about 1975 in the U.S. Navy, the large-scale carriers had been classified as "attack aircraft carriers" and the smaller carriers as "anti-submarine aircraft carriers." Since helicopter carriers have very little built-in attack capability and they primarily fulfill roles such as defensive antisubmarine warfare, the Japanese government continues to argue that the prohibition does not extend to the new helicopter carriers.

In November 2009, the JMSDF announced plans for an even larger "helicopter carrier". The first one of these ships was laid down in 2012.[11][12][13]

The submarine fleet of the JMSDF consists of some of the most technologically advanced diesel-electric submarines in the world. This is due to careful defense planning in which the submarines are routinely retired from service ahead of schedule and replaced by more advanced models.[14] In 2010 it was announced that the Japanese submarine fleet would be increased in size for the first time in 36 years.[2]

International activities

Mission in the Indian Ocean

Destroyers and combat support ships of Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force were dispatched to the Indian Ocean from 2001 to 2008 to participate in OEF-MIO (Operation Enduring Freedom-Maritime Interdiction Operation).[15] Their mission is to prevent the marine transportation of illegal weapons and ammunition, and the drugs which fund terrorist activity. Since 2004, the JMSDF has provided ships of foreign forces with fuel for their ships and ship-based helicopters, as well as fresh water.

This was the third time Japanese military vessels had been dispatched overseas since World War II, following the deployments of mine-sweeping units during the Korean War and the Persian Gulf War. The law enabling the mission expired on 2 November 2007, and the operation was temporarily canceled due to a veto of a new bill authorizing the mission by the opposition-controlled upper chamber of the Japanese Diet. A new law was subsequently passed when the lower chamber overruled the veto, and the mission was resumed.

In January 2010, the defense minister ordered the Japanese navy to return from the Indian Ocean, fulfilling a government pledge to end the eight-year refueling mission. Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama refused to renew the law authorizing the mission, ignoring requests from the American government for continuation.[16]

Mission in Somalia

In May 2010, Japan announced its intention to build a permanent naval base in Djibouti, from which it will conduct operations to protect merchant shipping from Somali pirates.[17]

Military exercises and exchanges

The JMSDF and the U.S. Navy frequently carry out joint exercises and "U.S. Navy officials have claimed that they have a closer daily relationship with the JMSDF than any other navy in the world".[18] The JMSDF participates in RIMPAC, the annual multi-national military exercise near Hawaii that has been hosted by the U.S. Navy since 1980. The JMSDF dispatched a ship to the Russian Vladivostok harbor in July in 1996 to participate in the Russian Navy's 300th anniversary naval review. Vladimir Vinogradov came by ship to the Tokyo harbor in June 1997. The JMSDF has also conducted joint naval exercises with the Indian Navy.

- RIMPAC: Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force participated in RIMPAC after 1980.

- Pacific Shield (PSI): The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force has participated in Pacific Shield after 2004; and in 2007, the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force hosted the exercise.

- Pacific Reach: The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force has participated in the bi-annual submarine rescue exercise since 2000. In 2002, the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force hosted the exercise.

- Navy to Navy Talks: The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force holds regular naval conferences with its counterparts of Indonesia, Malaysia, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America.

- AEGIS Ballistic Missile Defense FTM: The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force has participated in the FTM after FTM-10. The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force carried out JFTM-1 in December 2007.

Equipment

Ships and submarines

The ship prefix JDS (Japanese Defense Ship) was used until 2008, at which time JMSDF ships started using the prefix JS (Japanese Ship) to reflect the upgrade of the Japanese Defense Agency to the Ministry of Defense. As of 2013, the JMSDF operates a total of 134 vessels, including; four helicopter destroyers (or helicopter carriers), six large aegis destroyers (or cruisers), two guided missile destroyers (DDG), 16 destroyers (DD), 13 small destroyers (or frigates), six destroyer escorts (or corvettes), 16 attack submarines, 29 mine countermeasure vessels, six patrol vessels, three landing ship tanks, 8 training vessels and a fleet of various auxiliary ships.[19] The fleet has a total displacement of approximately 450,000 tons.

Aircraft

The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force aviation maintains a large naval air force, including 191 fixed-wing aircraft and 148 helicopters. Most of these aircraft are used in anti-submarine warfare operations.

| Aircraft | Role | Versions | Quantity[20] | Note | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed-wing aircraft | ||||||

| Lockheed P-3 Orion | Maritime patrol ELINT Reconnaissance Equipment test ELINT trainer |

P-3C EP-3C OP-3C UP-3C UP-3D |

80 5 4 1 3 |

|||

| Kawasaki P-1 | Maritime patrol | XP-1 | 2 | Planned to replace the Lockheed P-3C Orion. More on order. | ||

| NAMC YS-11 | Utility transport | YS-11T | 3 | To be replaced by 6 used KC-130Rs entering service.[21] | ||

| KC-130 Hercules | Utility transport | KC-130R | 6 aircraft formerly retired now being refitted to enter service.[22] | |||

| Learjet 35 | Utility aircraft | U-36A | 4 | |||

| Beechcraft King Air | Utility aircraft/Liaison Trainer aircraft |

LC-90 TC-90 |

5 27 |

|||

| Fuji T-5 | Trainer aircraft | T-5 | 50 | |||

| ShinMaywa US-1 | Search and rescue | US-1A | 2 | |||

| ShinMaywa US-2 | Search and rescue | US-2 | 5 | Replacing the older US-1. | ||

| Helicopters | ||||||

| Mitsubishi SH-60 | Maritime helicopter | SH-60J SH-60K |

97 | Anti-submarine warfare. | ||

| CH-53E Super Stallion | Minesweeping helicopter | MH-53E | 10 | |||

| AgustaWestland AW101 | Minesweeping helicopter Transport helicopter |

MCH-101 CH-101 |

7 | 7 more on order. Replacing the MH-53E. | ||

| MD Helicopters MD 500 | Trainer helicopter | OH-6D OH-6J |

5 4 |

|||

| Eurocopter EC 135 | Trainer helicopter | TH-135 | 6 | 9 more on order. | ||

| UH-60 Black Hawk | Search and rescue | UH-60J | 19 | |||

Organization, formations and structure

The JMSDF is commanded by the Chief of the Maritime Staff. Its structure consists of the Maritime Staff Office, the Self Defense Fleet, five regional district commands, the air-training squadron and various support units, such as hospitals and schools. The Maritime Staff Office, located in Tokyo, serves the Chief of Staff in commanding and supervising the force.

The Self-Defense Fleet, headquartered at Yokosuka, consists of the JMSDF's military shipping. It is composed of four Escort Flotillas (based in Yokosuka, Sasebo, Maizuru and Kure), the Fleet Air Force headquartered at Atsugi, two Submarine Flotillas based at Kure and Yokosuka, two Mine-sweeping Flotillas based at Kure and Yokosuka and the Fleet Training Command at Yokosuka.[23]

Each Escort Flotilla is formed as an 8–8 fleet of 8 destroyers and 8 on-board helicopters, a modification of the old Japanese Navy fleet layout of 8 battleships and 8 cruisers. Each force is composed of one helicopter destroyer (DDH) acting as a command ship, two guided-missile destroyers (DDG) and 5 standard or ASW destroyers (DD). The JMSDF is planning to reorganize the respective Escort Flotillas into a DDH group and DDG group, enabling faster overseas deployments.

- JMSDF Chief of Staff / Maritime Staff Office

- Self Defense Fleet (Mobile Flotilla)

- Fleet Escort Force

- Escort Flotilla 1 (Yokosuka)

- Escort Squadron 1 (DDG,DDH,DDx2)

- Escort Squadron 5 (DDG,DDx3)

- Escort Flotilla 2 (Sasebo)

- Escort Squadron 2 (DDG,DDH,DDx2)

- Escort Squadron 6 (DDG,DDx3)

- Escort Flotilla 3 (Maizuru)

- Escort Squadron 3 (DDG,DDH,DDx2)

- Escort Squadron 7 (DDG,DDx3)

- Escort Flotilla 4 (Kure)

- Escort Squadron 4 (DDG,DDH,DDx2)

- Escort Squadron 8 (DDG,DDx3)

- Fleet Training Command

- 1st Replenishment Squadron

- 1st Transportation Squadron

- Escort Flotilla 1 (Yokosuka)

- Fleet Air Force

- Fleet Air Wing 1 (P-3C UH-60J)

- Fleet Air Wing 2 (P-3C UH-60J)

- Fleet Air Wing 4 (P-3C UH-60J)

- Fleet Air Wing 5 (P-3C UH-60J)

- Fleet Air Wing 21 (SH-60J/K)

- Fleet Air Wing 22 (SH-60J)

- Fleet Air Wing 31 (US-1A US-2 EP-3 OP-3C UP-3D LC-90 U-36A)

- Fleet Squadron 51 (P-3C UP-3C/D OP-3 SH-60J/K OH-6DA)

- Fleet Squadron 61 (YS-11M/MA LC-90)

- Fleet Squadron 111 (MH-53E MCH-101 CH-101)

- Fleet Submarine Force

- Submarine Flotilla 1

- Submarine Squadron 1

- Submarine Squadron 3

- Submarine Squadron 5

- Submarine Flotilla 2

- Submarine Squadron 2

- Submarine Squadron 4

- Submarine Training Command

- Submarine Flotilla 1

- Mine Warfare Force

- Fleet Research & Development Command

- Fleet Intelligence Command

- Oceanographic Command

- Fleet Escort Force

- Air Training Command

- Maritime Material Command

- Ship Supply Depot

- Air Supply Depot

- Training Squadron

- Communication Command

- Criminal Investigation Command

- JMSDF Staff College

- Maritime Officer Candidate School

- 1st Service School

- 2nd Service School

- 3rd Service School

- 4th Service School

- Self Defense Fleet (Mobile Flotilla)

District Forces

Five district units act in concert with the fleet to guard the waters of their jurisdictions and provide shore-based support. Each district is home to a major JMSDF base and its supporting troops and staff. Furthermore, each district is home to one or two regional escort squadrons, composed of two to three destroyers or destroyer escorts (DE). The destroyers tend to be of older classes, mainly former escort force ships. The destroyer escorts, on the other hand, tend to be purpose built vessels. Each district also has a number of minesweeping ships.

Fleet Air Force

The Fleet Air Force is tasked with patrol, ASW and rescue tasks. It is composed primarily of 7 aviation groups. Prominent bases are maintained at Kanoya, Hachinohe, Atsugi, Naha, Tateyama, Oomura and Iwakuni. The Fleet Air Force is built up mainly with patrol aircraft such as the Lockheed P-3 Orion, rescue aircraft such as the US-1A and helicopters such as the SH-60J. In the JMSDF, helicopters deployed to each escort force are actually members of Fleet Air Force squadrons based on land.

Special Forces

Special Forces units consist of the following:

- SBU (Special Boarding Unit)

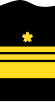

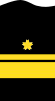

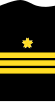

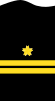

Ranks

The following details the officer ranks of the JMSDF, showing the Japanese rank, the English translation and the NATO equivalent.

- Commissioned Officers

| Japanese Rank (in Japanese) | Japanese Rank (Translated) | Japanese Rank (in English) | NATO Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| 幕僚長たる海将 (Bakuryō-chō taru Kaishō) | Chief of Staff Admiral | Admiral | OF-9 |

| 海将 (Kaishō) | Admiral | Vice-Admiral | OF-8 |

| 海将補 (Kaishō-ho) | Assistant Admiral | Rear-Admiral | OF-7 |

| 1等海佐 (Ittō Kaisa) | Captain 1st Rank | Captain | OF-5 |

| 2等海佐 (Nitō Kaisa) | Captain 2nd Rank | Commander | OF-4 |

| 3等海佐 (Santō Kaisa) | Captain 3rd Rank | Lieutenant Commander | OF-3 |

| 1等海尉 (Ittō Kaii) | Lieutenant 1st Rank | Lieutenant | OF-2 |

| 2等海尉 (Nitō Kaii)] | Lieutenant 2nd Rank | Lieutenant Junior Grade | OF-1 |

| 3等海尉 (Santō Kaii) | Lieutenant 3rd Rank | Ensign | OF-1 |

- Warrant officers

| 准海尉 (Jun Kaii) | Associate Lieutenant | Warrant Officer | OR-9 |

- Non-Commissioned Officers

| 海曹長 (Kaisō-chō) | Chief Petty Officer | Chief Petty Officer | OR-8 |

| 1等海曹 (Ittō Kaisō) | Petty Officer 1st Class | Petty Officer 1st Class | OR-7 |

| 2等海曹 (Nitō Kaisō) | Petty Officer 2nd Class | Petty Officer 2nd Class | OR-6 |

| 3等海曹 (Santō Kaisō) | Petty Officer 3rd Class | Petty Officer 3rd Class | OR-5 |

- Enlisted

| 海士長 (Kaishi-chō) | Chief Seaman | Leading Seaman | OR-4 |

| 1等海士 (Ittō Kaishi) | Seaman 1st Class | Seaman | OR-3 |

| 2等海士 (Nitō Kaishi) | Seaman 2nd Class | Seaman Apprentice | OR-2 |

| 3等海士 (Santō Kaishi) | Seaman 3rd Class | Seaman Recruit | OR-1 |

Ranks are listed with the lower rank at right.

Culture and naming conventions

Although Japan's Ground Self-Defense Force has dropped traditions association with the Imperial Japanese Army, the JMSDF has maintained these historic links with the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). Today's JMSDF continues to use the same martial songs, naval flags, signs and technical terms as the IJN. For example, the official flag of the JMSDF is the same as that used by the IJN. Also, the JMSDF tradition of eating Japanese curry every Friday lunch originated with the IJN.

Ships of the JMSDF, known as Japan Defense Ships (自衛艦; Ji'ei-Kan), are classified according to the following criteria:

| Class | Type | Symbol | Building # | # | Naming | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major class | Minor class | |||||

| Combatant Ship | Combatant Ship | Destroyer | DD | 1601- | 101- | Names of natural phenomena in the heavens or the atmosphere, mountains, rivers or regions |

| Destroyer escort | DE | 1201- | 201- | |||

| Submarine | SS | 8001- | 501- | Names of natural phenomena in the ocean or maritime animals | ||

| Mine Warfare Ship | Minesweeper Ocean | MSO | 201- | 301- | Names of islands, straits, channels or one that added a number to the type | |

| Minesweeper Coast | MSC | 301- | 601- | |||

| Minesweeping Controller | MCL | - | 721- | |||

| Minesweeper Tender | MST | 462- | 461- | |||

| Patrol Combatant Craft | Patrol Guided Missile Boat | PG | 821- | 821- | Names of birds, grass or one that added a number to the type | |

| Patrol Boat | PB | 921- | 901- | |||

| Amphibious Ship | Landing Ship, Tank | LST | 4101- | 4001- | Names of peninsulas, capes or one that added a number to the type | |

| Landing Ship Utility | LSU | 4171- | 4171- | |||

| Landing Craft Utility | LCU | 2001- | 2001- | |||

| Landing Craft Air Cushioned | LCAC | - | 2001- | |||

| Auxiliary Ship | Auxiliary Ship | Training Ship | TV | 3501- | 3501- | Names of places of natural beauty and historic interest or one that added a number to the type or the model |

| Training Submarine | TSS | - | - | |||

| Training Support Ship | ATS | 4201- | 4201- | |||

| Multipurpose Support Ship | AMS | - | - | |||

| Oceanographic Research Ship | AGS | 5101- | 5101- | |||

| Ocean Surveillance Ship | AOS | 5201- | 5201- | |||

| Ice breaker | AGB | 5001- | 5001- | |||

| Cable Repairing Ship | ARC | 1001- | 481- | |||

| Submarine Rescue Ship | ASR | 1101- | 401- | |||

| Submarine Rescue Tender | AS | 1111- | 405- | |||

| Experimental Ship | ASE | 6101- | 6101- | |||

| Fast Combat Support Ship | AOE | 4011- | 421- | |||

| Service Utility Ship | ASU | - | 7001- | |||

| Service Utility Craft | ASU | 81- | 61- | |||

| Service Yacht | ASY | 91- | 91- | |||

Recruitment and training

JMSDF recruits receive three months of basic training followed by courses in patrol, gunnery, mine sweeping, convoy operations and maritime transportation. Flight students, all upper-secondary school graduates, enter a two-year course. Officer candidate schools offer six-month courses to qualified enlisted personnel and those who have completed flight school.

Graduates of four-year universities, the four-year National Defense Academy, and particularly outstanding enlisted personnel undergo a one-year officer course at the Officer Candidate School at Etajima (site of the former Imperial Naval Academy). The JMSDF also operates a staff college in Tokyo for senior officers.

The large volume of coastal commercial fishing and maritime traffic around Japan limits in-service sea training, especially in the relatively shallow waters required for mine laying, mine sweeping and submarine rescue practice. Training days are scheduled around slack fishing seasons in winter and summer—providing about ten days during the year.

The JMSDF maintains two oceangoing training ships and conducted annual long-distance on-the-job training for graduates of the one-year officer candidate school.[23]

See also

- Imperial Japanese Navy

- Japanese ship naming conventions

- Military ranks and insignia of the Japan Self-Defense Forces

References

- ^ JMSDF 護衛艦 (DD)

- ^ JMSDF 潜水艦 (SS)

- ^ Library of Congress Country Studies, Japan> National Security> Self-Defense Forces> Early Development

- ^ Marcel Thach. "The Madness of Toyotomi Hideyoshi". The Samurai Archives. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- ^ George Samson (1961). A History of Japan, 1334–1615. Stanford University Press. p. 309. ISBN 0-8047-0525-9.

- ^ Schauffelen, Otmar. (2005). Chapman Great Sailing Ships of the World, p. 186.

- ^ Schencker, J. Charles. (1999). “The Imperial Japanese Navy and the Constructed Consciousness of a South Seas Destiny, 1872–1921,” Modern Asian Studies 33, no. 4 (1999 October 1999): 769–96.

- ^ a b Woolley, Peter J. (1996). "The Kata of Japan's Naval Forces," Naval War College Review, XLIX, 2: 59–69.

- ^ "海洋白書 2004". Nippon Foundation. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ "Japanese Aircraft Carrier". Global Security. 3 August 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ Demetriou, Danielle (23 November 2009). "Japan to build fleet's biggest helicopter destroyer to fend off China". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ http://www.bucharestherald.com/worldnews/43-worldnews/7538-japan-to-build-fleets-biggest-helicopter-destroyer-to-fend-off-china

- ^ http://www.ihi.co.jp/ihi/press/2011/2012-1-27/index.html

- ^ The Next Arms Race

- ^ "About activity based on Antiterrorism Law". Japan Ministry of Defense. Archived from the original on 28 January 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ "Japan: Navy Ends Mission in Support of Afghan War"

- ^ upi.com 11 May 2010, Japan to build navy base in Gulf of Aden

- ^ CRS RL33740 The Changing U.S.-Japan Alliance: Implications for U.S. Interests

- ^ http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/japan/ship.htm

- ^ "World Air Forces 2013". Flightglobal.com

- ^ [1]

- ^ Sale Gives New Life to Excess C-130s - Defense-Aerospace.com, March 7, 2013

- ^ a b Dolan, Ronald (1992). "8". Japan : A Country Study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 0-8444-0731-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) See section 2: "The Self Defense Forces"

Further reading

- Auer, James. The Postwar Rearmament of Japanese Maritime Forces, 1945–1971. New York: Praeger, 1973. ISBN 0-275-28633-9

- Auer, James. "Japan's Changing Defense Policy," The New Pacific Security Environment. Ralph A. Cossa, ed. Wash. D.C.: National Defense University, 1993.

- Jane's Intelligence Review, February 1992.

- Jane's Defence Weekly 17 August 1991

- Midford, Paul. “Japan’s Response to Terror: Dispatching the SDF to the Arabian Sea,” Asian Survey, 43:2 (March/April 2003).

- Rubinstein, G.A. and J. O'Connell. "Japan's Maritime Self-Defense Forces," Naval Forces. 11: 2 (1990).

- Sekino, Hideo. "Japan and Her Maritime Defense," U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, (May 1971).

- Sekino, Hideo. "A Diagnosis of our Maritime Self-Defense Force," Sekai no Kansen (Ships of the World), November 1970.

- Takei, Tomohisa,"Japan Maritime Self Defense Force in the New Maritime Era," Hatou, 34: 4(Novermber 2008).

- Tsukigi, Shinji, “External and Internal Factors Shaping The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF).” Monterey, Cal.: Naval Postgraduate School, June 1993. Master’s thesis.

- Wile, Ted Shannon. Sealane Defense: An Emerging Role for the JMSDF?. Master's Thesis, Naval Postgraduate School (1981).

- Woolley, Peter J. "Japan's 1991 Minesweeping Decision: An Organizational Response," Asian Survey 36:8 (1996).

- Woolley, Peter J. Japan’s Navy: Politics and Paradox 1971–2000. London: Lynne-Reinner: 2000. ISBN 1-55587-819-9

- Yamaguchi, Jiro. "The Gulf War and the Transformation of Japanese Constitutional Politics," Journal of Japanese Studies, Vol. 18 (Winter 1992).

- Young, P. Lewis. "The Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Forces: Major Surface Combatants Destroyers and Frigates," Asian Defense Journal (1985).