Neutron: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 82.47.163.253 (talk): nonconstructive edits (HG) |

Make consistent with Proton |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

| name = Neutron |

| name = Neutron |

||

| image = [[Image:Quark structure neutron.svg|250px]] |

| image = [[Image:Quark structure neutron.svg|250px]] |

||

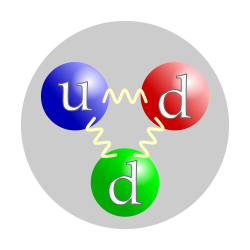

| caption = The [[quark]] structure of the neutron. (The color assignment of individual quarks is not important |

| caption = The [[quark]] structure of the neutron. (The color assignment of individual quarks is not important, only that all three colors are present.) |

||

| num_types = |

| num_types = |

||

| composition = 1 [[up quark]], 2 [[down quark]]s |

| composition = 1 [[up quark]], 2 [[down quark]]s |

||

Revision as of 18:20, 21 April 2014

The quark structure of the neutron. (The color assignment of individual quarks is not important, only that all three colors are present.) | |

| Classification | Baryon |

|---|---|

| Composition | 1 up quark, 2 down quarks |

| Statistics | Fermionic |

| Family | Hadron |

| Interactions | Gravity, Weak, Strong, Electromagnetic |

| Symbol | n , n0 , N0 |

| Antiparticle | Antineutron |

| Theorized | Ernest Rutherford[1][2] (1920) |

| Discovered | James Chadwick[1] (1932) |

| Mass | 1.674927351(74)×10−27 kg[3] 939.565378(21) MeV/c2[3] 1.00866491600(43) u[3] |

| Mean lifetime | 881.5(15) s (free) |

| Electric charge | 0 e 0 C |

| Electric dipole moment | < 2.9×10−26 e·cm |

| Electric polarizability | 1.16(15)×10−3 fm3 |

| Magnetic moment | −0.96623647(23)×10−26 J·T−1[3] −1.04187563(25)×10−3 μB[3] −1.91304272(45) μN[3] |

| Magnetic polarizability | 3.7(20)×10−4 fm3 |

| Spin | 1⁄2 |

| Isospin | 1⁄2 |

| Parity | +1 |

| Condensed | I(JP) = 1⁄2(1⁄2+) |

The neutron is a subatomic hadron particle that has the symbol

n

or

n0

. Neutrons have no net electric charge and a mass slightly larger than that of a proton. With the exception of hydrogen-1, the nucleus of every atom consists of at least one or more of both protons and neutrons. Protons and neutrons are collectively referred to as "nucleons". Since interacting protons have a mutual electromagnetic repulsion that is stronger than their attractive nuclear interaction, neutrons are often a necessary constituent within the atomic nucleus that allows a collection of protons to stay atomically bound (see diproton & neutron-proton ratio).[4] Neutrons bind with protons and one another in the nucleus via the nuclear force, effectively stabilizing it. The number of neutrons in the nucleus of an atom is referred to as its neutron number, which reveals the specific isotope of that atom. For example, the abundant carbon-12 isotope has 6 protons and 6 neutrons, whereas the rare radioactive carbon-14 isotope also has 6 protons but, instead, 8 neutrons. Elements may be found in nature as only one isotope or with as many as 10 isotopes (manganese and tin, respectively).

While the bound neutrons in nuclei can be stable (depending on the nuclide), free neutrons are unstable; they undergo beta decay with a mean lifetime of just under 15 minutes (881.5±1.5 s).[5] Free neutrons are produced in nuclear fission and fusion. Dedicated neutron sources like neutron generators, research reactors and spallation sources produce free neutrons for use in irradiation and in neutron scattering experiments. Even though it is not a chemical element, the free neutron is sometimes included in tables of nuclides.[6]

The neutron has been key to the production of nuclear power. The neutron was discovered in 1932, and in 1933, it was realized that it might mediate a nuclear chain reaction. In the 1930s, neutrons were used to produce many different types of nuclear transmutations. When nuclear fission was discovered in 1938, it became clear that, if the process also produced neutrons, this might be the mechanism to produce the neutrons for a chain reaction. This was proven in 1939, opening the path to nuclear power production. These events and findings led directly to the first self-sustaining, man-made, nuclear chain reaction (Chicago Pile-1, 1942) and to the first nuclear weapons (1945).

Discovery

In 1920, Ernest Rutherford conceived the possible existence of the neutron.[2][7] In particular, Rutherford considered that the disparity found between the atomic number of an atom and its atomic mass could be explained by the existence of a neutrally charged particle within the atomic nucleus. He considered the neutron to be a neutral double consisting of an electron orbiting a proton.[8]

Through the 1920s, physicists had generally accepted an (incorrect) model of the atomic nucleus as composed of protons and electrons.[9][10] It was known that atomic nuclei usually had about half as many positive charges than if they were composed completely of protons, and in existing models this was often explained by proposing that nuclei also contained some "nuclear electrons" to neutralize the excess charge. Thus, the nitrogen-14 nucleus would be composed of 14 protons and 7 electrons to give it a charge of +7 but a mass of 14 atomic mass units.

The new quantum mechanics implied that a particle as light as the electron could not be contained in a region as small as the nucleus with any reasonable energy. In 1930 Viktor Ambartsumian and Dmitri Ivanenko in the USSR found that, contrary to the prevailing opinion of the time, the nucleus cannot consist of protons and electrons. They proved that some neutral particles must be present besides the protons.[11][12]

In 1931, Walther Bothe and Herbert Becker in Germany found that if the very energetic alpha particles emitted from polonium fell on certain light elements, specifically beryllium, boron, or lithium, an unusually penetrating radiation was produced. At first this radiation was thought to be gamma radiation, although it was more penetrating than any gamma rays known, and the details of experimental results were very difficult to interpret on this basis.[13][14] The next important contribution was reported in 1932 by Irène Joliot-Curie and Frédéric Joliot in Paris.[15] They showed that if this unknown radiation fell on paraffin, or any other hydrogen-containing compound, it ejected protons of very high energy. This was not in itself inconsistent with the assumed gamma ray nature of the new radiation, but detailed quantitative analysis of the data became increasingly difficult to reconcile with such a hypothesis.

In 1932, James Chadwick performed a series of experiments at the University of Cambridge, showing that the gamma ray hypothesis was untenable.[16] He suggested that the new radiation consisted of uncharged particles of approximately the mass of the proton, and he performed a series of experiments verifying his suggestion.[17] These uncharged particles were called neutrons, apparently from the Latin root for neutral and the Greek ending -on (by imitation of electron and proton).[18]

Proton–neutron model of the nucleus

After Chadwick's discovery, and given the problems of the proton-electron model,[9][10] it was quickly accepted that the atomic nucleus is composed of protons and neutrons.

In particular, molecular spectroscopy of dinitrogen (N2) showed that transitions originating from even rotational levels are more intense than those from odd levels, which means that the even levels are more populated. According to quantum mechanics and the Pauli exclusion principle, this implies that the spin of the N-14 nucleus is an integer multiple of ħ (the Planck constant h divided by 2π).[19][20] This was contrary to the proton-electron model as it was known that both protons and electrons carried an intrinsic spin of 1⁄2 ħ, and there was no way to arrange an odd number (21) of spins ±1⁄2 ħ to give a spin of 1 ħ.

The proton-neutron model explained this puzzle however. Fermi's theory of beta-decay requires that the neutron is also a particle of spin ±1⁄2 ħ to obey the law of conservation of angular momentum. When nitrogen-14 was proposed to consist of 3 pairs each of protons and neutrons, with an additional unpaired neutron and proton each contributing a spin of 1⁄2 ħ in the same direction for a total spin of 1 ħ, the model became viable. Soon, nuclear neutrons were used to naturally explain spin differences in many different nuclides in the same way, and the neutron as a basic structural unit of atomic nuclei was accepted.

Atomic spectra possess hyperfine structure due to the nucleus, but the spectra are uninfluenced by the spins of the supposed nuclear electrons. This was also somewhat mysterious[9] until it was realized that there are no nuclear electrons in the nucleus.

Intrinsic properties

Stability and beta decay

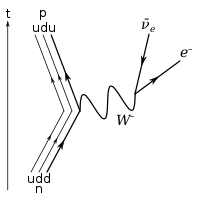

Under the Standard Model of particle physics, because the neutron consists of three quarks, the only possible decay mode without a change of baryon number is for one of the quarks to change flavour via the weak interaction. The neutron consists of two down quarks with charge −1⁄3 e and one up quark with charge +2⁄3 e, and the decay of one of the down quarks into a lighter up quark can be achieved by the emission of a W boson. This means the neutron decays into a proton (which contains one down and two up quarks), an electron, and an electron antineutrino.

Free neutron decay

Outside the nucleus, free neutrons are unstable and have a mean lifetime of 881.5±1.5 s (about 14 minutes, 42 seconds); therefore the half-life for this process (which differs from the mean lifetime by a factor of ln(2) = 0.693) is 611.0±1.0 s (about 10 minutes, 11 seconds).[5] Free neutrons decay by emission of an electron and an electron antineutrino to become a proton, a process known as beta decay:[21]

n0

→

p+

+

e−

+

ν

e

The decay energy for this process (based on the masses of neutrino, proton, and electron) is 0.782343 MeV. The maximal energy of the beta decay electron (in the process wherein the neutrino receives a vanishingly small amount of kinetic energy) has been measured at 0.782 ± .013 MeV.[22] The latter number is not well-enough measured to determine the rest mass of the neutrino as well as it is constrained by many other methods.

A small fraction (about one in 1000) of free neutrons decay with the same products, but add an extra particle in the form of an emitted gamma ray:

n0

→

p+

+

e−

+

ν

e +

γ

This gamma ray may be thought of as a sort of "internal bremsstrahlung" that arises as the emitted beta particle interacts with the charge of the proton in an electromagnetic way. Internal bremsstrahlung gamma ray production is also a minor feature of beta decays of bound neutrons (as discussed below).

A very small minority of neutron decays (about four per million) are so-called "two-body decays", in which the proton, electron and antineutrino are produced, but the electron fails to gain the 13.6 eV necessary energy to escape the proton, and therefore simply remains bound to it, as a neutral hydrogen atom. In this type of free neutron decay, in essence all of the neutron decay energy is carried off by the antineutrino.

Bound neutron decay

Neutrons in unstable nuclei can also decay in the most common manner above. However, inside a nucleus, protons can also transform into a neutron via inverse beta decay. This transformation occurs by emission of an antielectron (also called positron) and an electron neutrino:

p+

→

n0

+

e+

+

ν

e

The transformation of a proton to a neutron inside of a nucleus is also possible through electron capture:

p+

+

e−

→

n0

+

ν

e

Positron capture by neutrons in nuclei that contain an excess of neutrons is also possible, but is hindered because positrons are repelled by the nucleus, and quickly annihilate when they encounter electrons.

When bound inside of a nucleus, the energetic instability of a single neutron to beta decay is balanced against the instability that would be acquired by the nucleus as a whole if an additional proton were to appear by beta decay, and thus participate in repulsive interactions with the other protons that are already present in the nucleus. As such, although free neutrons are unstable, bound neutrons in a nucleus are not necessarily so. The same reasoning explains why protons, which are stable in empty space, may transform into neutrons when bound inside of a nucleus.

Electric dipole moment

The Standard Model of particle physics predicts a tiny separation of positive and negative charge within the neutron leading to a permanent electric dipole moment.[23] The predicted value is, however, well below the current sensitivity of experiments. From several unsolved puzzles in particle physics, it is clear that the Standard Model is not the final and full description of all particles and their interactions. New theories going beyond the Standard Model generally lead to much larger predictions for the electric dipole moment of the neutron. Currently, there are at least four experiments trying to measure for the first time a finite neutron electric dipole moment, including:

- Cryogenic neutron EDM experiment being set up at the Institut Laue–Langevin[24]

- nEDM experiment under construction at the new UCN source at the Paul Scherrer Institute[25]

- nEDM experiment being envisaged at the Spallation Neutron Source[26]

- nEDM experiment being built at the Institut Laue–Langevin[27]

Magnetic moment

Even though the neutron is a neutral particle, the magnetic moment of a neutron is not zero. Since the neutron is a neutral particle, the magnetic moment is an indication of substructure. For a time, the neutron was thought to be made of a proton, with a charge of +1 e and an electron, with a charge of −1 e, whose charge would cancel out. However, since the advent of the quark model, it is now known that the neutron is made of one up quark (charge of +2/3 e) and two down quarks (charge of −1/3 e). because it is a composite particle containing three charged quarks.[28]

Anti-neutron

The antineutron is the antiparticle of the neutron. It was discovered by Bruce Cork in the year 1956, a year after the antiproton was discovered. CPT-symmetry puts strong constraints on the relative properties of particles and antiparticles, so studying antineutrons yields provide stringent tests on CPT-symmetry. The fractional difference in the masses of the neutron and antineutron is (9±6)×10−5. Since the difference is only about two standard deviations away from zero, this does not give any convincing evidence of CPT-violation.[5]

Structure and geometry of charge distribution

An article published in 2007 featuring a model-independent analysis concluded that the neutron has a negatively charged exterior, a positively charged middle, and a negative core.[29] In a simplified classical view, the negative "skin" of the neutron assists it to be attracted to the protons with which it interacts in the nucleus. However, the main attraction between neutrons and protons is via the nuclear force, which does not involve charge.

Neutron compounds

Dineutrons and tetraneutrons

The existence of stable clusters of 4 neutrons, or tetraneutrons, has been hypothesised by a team led by Francisco-Miguel Marqués at the CNRS Laboratory for Nuclear Physics based on observations of the disintegration of beryllium-14 nuclei. This is particularly interesting because current theory suggests that these clusters should not be stable.

The dineutron is another hypothetical particle. In 2012, Spyrou from Michigan State University and coworkers reported that they observed, for the first time, the dineutron emission in the decay of 16Be. The dineutron character is evidenced by a small emission angle between the two neutrons. The authors measured the two-neutron separation energy to be 1.35(10) MeV, in good agreement with shell model calculations, using standard interactions for this mass region.[30]

Neutronium and neutron stars

At extremely high pressures and temperatures, nucleons and electrons are believed to collapse into bulk neutronic matter, called neutronium. This is presumed to happen in neutron stars.

The extreme pressure inside a neutron star may deform the neutrons into a cubic symmetry, allowing tighter packing of neutrons.[31]

Detection

The common means of detecting a charged particle by looking for a track of ionization (such as in a cloud chamber) does not work for neutrons directly. Neutrons that elastically scatter off atoms can create an ionization track that is detectable, but the experiments are not as simple to carry out; other means for detecting neutrons, consisting of allowing them to interact with atomic nuclei, are more commonly used. The commonly used methods to detect neutrons can therefore be categorized according to the nuclear processes relied upon, mainly neutron capture or elastic scattering. A good discussion on neutron detection is found in chapter 14 of the book Radiation Detection and Measurement by Glenn F. Knoll (John Wiley & Sons, 1979).

Neutron detection by neutron capture

A common method for detecting neutrons involves converting the energy released from neutron capture reactions into electrical signals. Certain nuclides have a high neutron capture cross section, which is the probability of absorbing a neutron. Upon neutron capture, the compound nucleus emits more easily detectable radiation, for example an alpha particle, which is then detected. The nuclides 3

He

, 6

Li

, 10

B

, 233

U

, 235

U

, 237

Np

and 239

Pu

are useful for this purpose.

Neutron detection by elastic scattering

Neutrons can elastically scatter off nuclei, causing the struck nucleus to recoil. Kinematically, a neutron can transfer more energy to light nuclei such as hydrogen or helium than to heavier nuclei. Detectors relying on elastic scattering are called fast neutron detectors. Recoiling nuclei can ionize and excite further atoms through collisions. Charge and/or scintillation light produced in this way can be collected to produce a detected signal. A major challenge in fast neutron detection is discerning such signals from erroneous signals produced by gamma radiation in the same detector.

Fast neutron detectors have the advantage of not requiring a moderator, and therefore being capable of measuring the neutron's energy, time of arrival, and in certain cases direction of incidence.

Production and sources

Free neutrons are unstable, although they have the longest half-life of any unstable sub-atomic particle by several orders of magnitude. Their half-life is still only about 10 minutes, so they can be obtained only from sources that produce them freshly. These include certain types of radioactive decay (spontaneous fission and neutron emission), and from certain nuclear reactions. Convenient nuclear reactions include tabletop reactions such as natural alpha and gamma bombardment of certain nuclides, often beryllium or deuterium, and induced nuclear fission, such as occurs in nuclear reactors. In addition, high-energy nuclear reactions (such as occur in cosmic radiation showers or accelerator collisions) also produce neutrons from disintigration of target nuclei. Small (tabletop) particle accelerators optimized to produce free neutrons in this way, are called neutron generators.

In practice, the most commonly used small laboratory sources of neutrons use radioactive decay to power neutron production. One noted neutron-producing radioisotope, californium-252 decays (half-life 2.65 years) by spontaneous fission 3% of the time with production of 3.7 neutrons per fission, and is used alone as a neutron source from this process. Nuclear reaction sources (that involve two materials) powered by radioisotopes use an alpha decay source plus a beryllium target, or else a source of high-energy gamma radiation from a source that undergoes beta decay followed by gamma decay, which produces photoneutrons on interaction of the high energy gamma ray with ordinary stable beryllium, or else with the deuterium in heavy water. A popular source of the latter type is radioactive antimony-124 plus beryllium, a system with a half-life of 60.9 days, which can be constructed from natural antimony (which is 42.8% stable antimony-123) by activating it with neutrons in a nuclear reactor, then transported to where the neutron source is needed.[32]

Cosmic radiation interacting with the Earth's atmosphere continuously generates neutrons that can be detected at the surface. Even stronger neutron radiation is produced at the surface of Mars where the atmosphere is thick enough to generate neutrons from cosmic ray spallation, but not thick enough to provide significant protection from the neutrons produced. These neutrons not only produce a Martian surface neutron radiation hazard from direct downward-going neutron radiation but also produce a significant hazard from reflection of neutrons from the Martian surface, which will produce reflected neutron radiation penetrating upward into a Martian craft or habitat from the floor.[33]

Nuclear fission reactors naturally produce free neutrons; their role is to sustain the energy-producing chain reaction. The intense neutron radiation can also be used to produce various radioisotopes through the process of neutron activation, which is a type of neutron capture.

Experimental nuclear fusion reactors produce free neutrons as a waste product. However, it is these neutrons that possess most of the energy, and converting that energy to a useful form has proved a difficult engineering challenge. Fusion reactors that generate neutrons are likely to create radioactive waste, but the waste is composed of neutron-activated lighter isotopes, which have relatively short (50–100 years) decay periods as compared to typical half-lives of 10,000 years[citation needed] for fission waste, which is long due primarily to the long half-life of alpha-emitting transuranic actinides.[34]

Neutron beams and modification of beams after production

Free neutron beams are obtained from neutron sources by neutron transport. For access to intense neutron sources, researchers must go to a specialist neutron facility that operates a research reactor or a spallation source.

The neutron's lack of total electric charge makes it difficult to steer or accelerate them. Charged particles can be accelerated, decelerated, or deflected by electric or magnetic fields. These methods have little effect on neutrons. However, some effects may be attained by use of inhomogeneous magnetic fields because of the neutron's magnetic moment. Neutrons can be controlled by methods that include moderation, reflection, and velocity selection. Thermal neutrons can be polarized by transmission through magnetic materials in a method analogous to the Faraday effect for photons. Cold neutrons of wavelengths of 6–7 angstroms can be produced in beams of a high degree of polarization, by use of magnetic mirrors and magnetized interference filters.[35]

Uses

| Science with neutrons |

|---|

|

| Foundations |

| Neutron scattering |

| Other applications |

|

| Infrastructure |

|

| Neutron facilities |

The neutron plays an important role in many nuclear reactions. For example, neutron capture often results in neutron activation, inducing radioactivity. In particular, knowledge of neutrons and their behavior has been important in the development of nuclear reactors and nuclear weapons. The fissioning of elements like uranium-235 and plutonium-239 is caused by their absorption of neutrons.

Cold, thermal and hot neutron radiation is commonly employed in neutron scattering facilities, where the radiation is used in a similar way one uses X-rays for the analysis of condensed matter. Neutrons are complementary to the latter in terms of atomic contrasts by different scattering cross sections; sensitivity to magnetism; energy range for inelastic neutron spectroscopy; and deep penetration into matter.

The development of "neutron lenses" based on total internal reflection within hollow glass capillary tubes or by reflection from dimpled aluminum plates has driven ongoing research into neutron microscopy and neutron/gamma ray tomography.[36][37][38]

A major use of neutrons is to excite delayed and prompt gamma rays from elements in materials. This forms the basis of neutron activation analysis (NAA) and prompt gamma neutron activation analysis (PGNAA). NAA is most often used to analyze small samples of materials in a nuclear reactor whilst PGNAA is most often used to analyze subterranean rocks around bore holes and industrial bulk materials on conveyor belts.

Another use of neutron emitters is the detection of light nuclei, in particular the hydrogen found in water molecules. When a fast neutron collides with a light nucleus, it loses a large fraction of its energy. By measuring the rate at which slow neutrons return to the probe after reflecting off of hydrogen nuclei, a neutron probe may determine the water content in soil.

Beams of low energy neutrons are used in boron capture therapy to treat cancer. In boron capture therapy, the patient is given a drug that contains boron and that preferentially accumulates in the tumor to be targeted. The tumor is then bombarded with very low energy neutrons (although often higher than thermal energy) which are captured by the boron-10 isotope in the boron, which produces an excited state of boron-11 that then decays to produce lithium-7 and an alpha particle that have sufficient energy to kill the malignant cell, but insufficient range to damage nearby cells. For such a therapy to be applied to the treatment of cancer, a neutron source having an intensity of the order of billion (109) neutrons per second per cm2 is preferred. Such fluxes require a research nuclear reactor.

Protection

Exposure to free neutrons can be hazardous, since the interaction of neutrons with molecules in the body can cause disruption to molecules and atoms, and can also cause reactions that give rise to other forms of radiation (such as protons). The normal precautions of radiation protection apply: Avoid exposure, stay as far from the source as possible, and keep exposure time to a minimum. Some particular thought must be given to how to protect from neutron exposure, however. For other types of radiation, e.g. alpha particles, beta particles, or gamma rays, material of a high atomic number and with high density make for good shielding; frequently, lead is used. However, this approach will not work with neutrons, since the absorption of neutrons does not increase straightforwardly with atomic number, as it does with alpha, beta, and gamma radiation. Instead one needs to look at the particular interactions neutrons have with matter (see the section on detection above). For example, hydrogen-rich materials are often used to shield against neutrons, since ordinary hydrogen both scatters and slows neutrons. This often means that simple concrete blocks or even paraffin-loaded plastic blocks afford better protection from neutrons than do far more dense materials. After slowing, neutrons may then be absorbed with an isotope that has high affinity for slow neutrons without causing secondary capture-radiation, such as lithium-6.

Hydrogen-rich ordinary water affects neutron absorption in nuclear fission reactors: Usually, neutrons are so strongly absorbed by normal water that fuel-enrichment with fissionable isotope is required. The deuterium in heavy water has a very much lower absorption affinity for neutrons than does protium (normal light hydrogen). Deuterium is, therefore, used in CANDU-type reactors, in order to slow (moderate) neutron velocity, to increase the probability of nuclear fission compared to neutron capture.

Neutron temperature

Thermal neutrons

A thermal neutron is a free neutron that is Boltzmann distributed with kT = 0.0253 eV (4.0×10−21 J) at room temperature. This gives characteristic (not average, or median) speed of 2.2 km/s. The name 'thermal' comes from their energy being that of the room temperature gas or material they are permeating. (see kinetic theory for energies and speeds of molecules). After a number of collisions (often in the range of 10–20) with nuclei, neutrons arrive at this energy level, provided that they are not absorbed.

In many substances, thermal neutron reactions show a much larger effective cross-section than reactions involving faster neutrons, and thermal neutrons can therefore be absorbed more readily (i.e., with higher probability) by any atomic nuclei that they collide with, creating a heavier — and often unstable — isotope of the chemical element as a result.

Most fission reactors use a neutron moderator to slow down, or thermalize the neutrons that are emitted by nuclear fission so that they are more easily captured, causing further fission. Others, called fast breeder reactors, use fission energy neutrons directly.

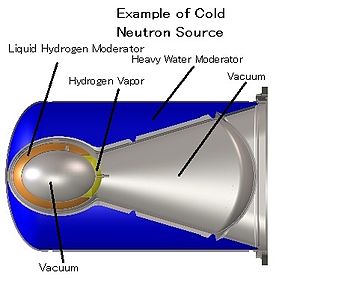

Cold neutrons

Cold neutrons are thermal neutrons that have been equilibrated in a very cold substance such as liquid deuterium. Such a cold source is placed in the moderator of a research reactor or spallation source. Cold neutrons are particularly valuable for neutron scattering experiments.[citation needed]

Ultracold neutrons

Ultracold neutrons are produced by inelastically scattering cold neutrons in substances with a temperature of a few kelvins, such as solid deuterium or superfluid helium. An alternative production method is the mechanical deceleration of cold neutrons.

Fission energy neutrons

A fast neutron is a free neutron with a kinetic energy level close to 1 MeV (1.6×10−13 J), hence a speed of ~14000 km/s (~ 5% of the speed of light). They are named fission energy or fast neutrons to distinguish them from lower-energy thermal neutrons, and high-energy neutrons produced in cosmic showers or accelerators. Fast neutrons are produced by nuclear processes such as nuclear fission. Neutrons produced in fission, as noted above, have a Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution of kinetic energies from 0 to ~14 MeV, a mean energy of 2 MeV (for U-235 fission neutrons), and a mode of only 0.75 MeV, which means that more than half of them do not qualify as fast (and thus have almost no chance of initiating fission in fertile materials, such as U-238 and Th-232).

Fast neutrons can be made into thermal neutrons via a process called moderation. This is done with a neutron moderator. In reactors, typically heavy water, light water, or graphite are used to moderate neutrons.

Fusion neutrons

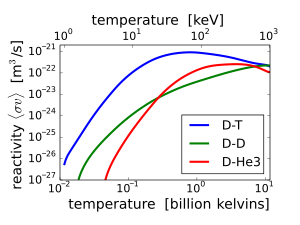

D-T (deuterium–tritium) fusion is the fusion reaction that produces the most energetic neutrons, with 14.1 MeV of kinetic energy and traveling at 17% of the speed of light. D-T fusion is also the easiest fusion reaction to ignite, reaching near-peak rates even when the deuterium and tritium nuclei have only a thousandth as much kinetic energy as the 14.1 MeV that will be produced.

14.1 MeV neutrons have about 10 times as much energy as fission neutrons, and are very effective at fissioning even non-fissile heavy nuclei, and these high-energy fissions produce more neutrons on average than fissions by lower-energy neutrons. This makes D-T fusion neutron sources such as proposed tokamak power reactors useful for transmutation of transuranic waste. 14.1 MeV neutrons can also produce neutrons by knocking them loose from nuclei.

On the other hand, these very high energy neutrons are less likely to simply be captured without causing fission or spallation. For these reasons, nuclear weapon design extensively utilizes D-T fusion 14.1 MeV neutrons to cause more fission. Fusion neutrons are able to cause fission in ordinarily non-fissile materials, such as depleted uranium (uranium-238), and these materials have been used in the jackets of thermonuclear weapons. Fusion neutrons also can cause fission in substances that are unsuitable or difficult to make into primary fission bombs, such as reactor grade plutonium. This physical fact thus causes ordinary non-weapons grade materials to become of concern in certain nuclear proliferation discussions and treaties.

Other fusion reactions produce much less energetic neutrons. D-D fusion produces a 2.45 MeV neutron and helium-3 half of the time, and produces tritium and a proton but no neutron the other half of the time. D-3He fusion produces no neutron.

Intermediate-energy neutrons

A fission energy neutron that has slowed down but not yet reached thermal energies is called an epithermal neutron.

Cross sections for both capture and fission reactions often have multiple resonance peaks at specific energies in the epithermal energy range. These are of less significance in a fast neutron reactor, where most neutrons are absorbed before slowing down to this range, or in a well-moderated thermal reactor, where epithermal neutrons interact mostly with moderator nuclei, not with either fissile or fertile actinide nuclides. However, in a partially moderated reactor with more interactions of epithermal neutrons with heavy metal nuclei, there are greater possibilities for transient changes in reactivity that might make reactor control more difficult.

Ratios of capture reactions to fission reactions are also worse (more captures without fission) in most nuclear fuels such as plutonium-239, making epithermal-spectrum reactors using these fuels less desirable, as captures not only waste the one neutron captured but also usually result in a nuclide that is not fissile with thermal or epithermal neutrons, though still fissionable with fast neutrons. The exception is uranium-233 of the thorium cycle, which has good capture-fission ratios at all neutron energies.

High-energy neutrons

These neutrons have much more energy than fission energy neutrons and are generated as secondary particles by particle accelerators or in the atmosphere from cosmic rays. They can have energies as high as tens of joules per neutron. These neutrons are extremely efficient at ionization and far more likely to cause cell death than X-rays or protons.[39][40]

See also

- Ionizing radiation

- Isotope

- List of particles

- Neutron capture nucleosynthesis

- Neutronium

- Neutron magnetic moment

- Neutron radiation and the Sievert radiation scale

- Nuclear reaction

- Thermal reactor

Neutron sources

Processes involving neutrons

References

- ^ a b 1935 Nobel Prize in Physics. Nobelprize.org. Retrieved on 2012-08-16.

- ^ a b Ernest Rutherford. Chemed.chem.purdue.edu. Retrieved on 2012-08-16.

- ^ a b c d e f Mohr, P.J.; Taylor, B.N. and Newell, D.B. (2011), "The 2010 CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants" (Web Version 6.0). The database was developed by J. Baker, M. Douma, and S. Kotochigova. (2011-06-02). National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, Maryland 20899.

- ^ Sir James Chadwick’s Discovery of Neutrons. ANS Nuclear Cafe. Retrieved on 2012-08-16.

- ^ a b c Nakamura, K (2010). "Review of Particle Physics". Journal of Physics G: Nuclear and Particle Physics. 37 (7A): 075021. Bibcode:2010JPhG...37g5021N. doi:10.1088/0954-3899/37/7A/075021. PDF with 2011 partial update for the 2012 edition The exact value of the mean lifetime is still uncertain, due to conflicting results from experiments. The Particle Data Group reports values up to six seconds apart (more than four standard deviations), commenting that "our 2006, 2008, and 2010 Reviews stayed with 885.7±0.8 s; but we noted that in light of SEREBROV 05 our value should be regarded as suspect until further experiments clarified matters. Since our 2010 Review, PICHLMAIER 10 has obtained a mean life of 880.7±1.8 s, closer to the value of SEREBROV 05 than to our average. And SEREBROV 10B[...] claims their values should be lowered by about 6 s, which would bring them into line with the two lower values. However, those reevaluations have not received an enthusiastic response from the experimenters in question; and in any case the Particle Data Group would have to await published changes (by those experimenters) of published values. At this point, we can think of nothing better to do than to average the seven best but discordant measurements, getting 881.5±1.5s. Note that the error includes a scale factor of 2.7. This is a jump of 4.2 old (and 2.8 new) standard deviations. This state of affairs is a particularly unhappy one, because the value is so important. We again call upon the experimenters to clear this up."

- ^ Nudat 2. Nndc.bnl.gov. Retrieved on 2010-12-04.

- ^ E. Rutherford (1920). "Nuclear Constitution of Atoms". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 97 (686): 374. Bibcode:1920RSPSA..97..374R. doi:10.1098/rspa.1920.0040.

- ^ Rutherford, E. (1920). "Bakerian Lecture. Nuclear Constitution of Atoms". Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 97 (686): 374. Bibcode:1920RSPSA..97..374R. doi:10.1098/rspa.1920.0040. JSTOR 93888.

- ^ a b c Brown, Laurie M. (1978). "The idea of the neutrino". Physics Today. 31 (9): 23. doi:10.1063/1.2995181.

- ^ a b Friedlander G., Kennedy J.W. and Miller J.M. (1964) Nuclear and Radiochemistry (2nd edition), Wiley, pp. 22–23 and 38–39

- ^ "V. A. Ambartsumian— a life in science" (PDF). Astrophysics. 51 (3): 280. 2008. Bibcode:2008Ap.....51..280T. doi:10.1007/s10511-008-9016-6.

- ^ Ambartsumian and Ivanenko (1930) "Об одном следствии теории дирака протонов и электронов" (On a Consequence of the Dirac Theory of Protons and Electrons), Доклады Академии Наук СССР (Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR / Proceedings of the USSR Academy of Sciences) Ser. A, no. 6, pages 153-155. Available in Russian on-line.

- ^ Bothe, W.; Becker, H. (1930). "Künstliche Erregung von Kern-γ-Strahlen". Zeitschrift für Physik. 66 (5–6): 289. Bibcode:1930ZPhy...66..289B. doi:10.1007/BF01390908.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Becker, H.; Bothe, W. (1932). "Die in Bor und Beryllium erregten γ-Strahlen". Zeitschrift für Physik. 76 (7–8): 421. Bibcode:1932ZPhy...76..421B. doi:10.1007/BF01336726.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Joliot-Curie, Irène and Joliot, Frédéric (1932). "Émission de protons de grande vitesse par les substances hydrogénées sous l'influence des rayons γ très pénétrants". Comptes Rendus. 194: 273.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chadwick, J. (1933). "Bakerian Lecture. The Neutron". Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 142 (846): 1. Bibcode:1933RSPSA.142....1C. doi:10.1098/rspa.1933.0152.

- ^ Chadwick, James (1932). "Possible Existence of a Neutron". Nature. 129 (3252): 312. Bibcode:1932Natur.129Q.312C. doi:10.1038/129312a0.

- ^ "Wolfgang Pauli". Sources in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences. 6. 1985: 105. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-78801-0_3. ISBN 978-3-540-13609-5.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Atkins, P.W. and J. de Paula, P.W. (2006) "Atkins' Physical Chemistry" (8th edition), W.H. Freeman, p. 451

- ^ Herzberg, G. (1950) Spectra of Diatomic Molecules (2nd edition), van Nostrand Reinhold, pp. 133–140

- ^ Particle Data Group Summary Data Table on Baryons. lbl.gov (2007). Retrieved on 2012-08-16.

- ^ Basic Ideas and Concepts in Nuclear Physics: An Introductory Approach, Third Edition K. Heyde Taylor & Francis 2004. Print ISBN 978-0-7503-0980-6. eBook ISBN 978-1-4200-5494-1. DOI: 10.1201/9781420054941.ch5. full text

- ^ "Pear-shaped particles probe big-bang mystery" (Press release). University of Sussex. 20 February 2006. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- ^ A cryogenic experiment to search for the EDM of the neutron. Hepwww.rl.ac.uk. Retrieved on 2012-08-16.

- ^ Search for the neutron electric dipole moment: nEDM. Nedm.web.psi.ch (2001-09-12). Retrieved on 2012-08-16.

- ^ SNS Neutron EDM Experiment. P25ext.lanl.gov. Retrieved on 2012-08-16.

- ^ Measurement of the Neutron Electric Dipole Moment. Nrd.pnpi.spb.ru. Retrieved on 2012-08-16.

- ^ Gell, Y.; Lichtenberg, D. B. (1969). "Quark model and the magnetic moments of proton and neutron". Il Nuovo Cimento A. Series 10. 61: 27. doi:10.1007/BF02760010.

- ^ Miller, G.A. (2007). "Charge Densities of the Neutron and Proton". Physical Review Letters. 99 (11): 112001. Bibcode:2007PhRvL..99k2001M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.112001.

- ^ Spyrou, A. (2012). "First Observation of Ground State Dineutron Decay: 16Be". Physical Review Letters. 108 (10): 102501. Bibcode:2012PhRvL.108j2501S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.102501. PMID 22463404.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Felipe J. Llanes-Estrada, Gaspar Moreno Navarro., Felipe J.; Gaspar Moreno Navarro (2011). "Cubic neutrons". arXiv:1108.1859 [nucl-th].

{{cite arXiv}}: Unknown parameter|version=ignored (help) - ^ Byrne, J. Neutrons, Nuclei, and Matter, Dover Publications, Mineola, New York, 2011, ISBN 0486482383, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Clowdsley, MS; Wilson, JW; Kim, MH; Singleterry, RC; Tripathi, RK; Heinbockel, JH; Badavi, FF; Shinn, JL (2001). "Neutron Environments on the Martian Surface" (PDF). Physica Medica. 17 (Suppl 1): 94–6. PMID 11770546.

- ^ Science/Nature | Q&A: Nuclear fusion reactor. BBC News (2006-02-06). Retrieved on 2010-12-04.

- ^ Byrne, J. Neutrons, Nuclei, and Matter, Dover Publications, Mineola, New York, 2011, ISBN 0486482383, p. 453.

- ^ Kumakhov, M. A. (1992). "A neutron lens". Nature. 357 (6377): 390–391. Bibcode:1992Natur.357..390K. doi:10.1038/357390a0.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Physorg.com, "New Way of 'Seeing': A 'Neutron Microscope'". Physorg.com (2004-07-30). Retrieved on 2012-08-16.

- ^ "NASA Develops a Nugget to Search for Life in Space". NASA.gov (2007-11-30). Retrieved on 2012-08-16.

- ^ "Facing up to secondary neutrons". Medical Physics Web. May 23, 2008. Retrieved 2011-02-08.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ Heilbronn, L.; Nakamura, T; Iwata, Y; Kurosawa, T; Iwase, H; Townsend, LW (2005). "Expand+Overview of secondary neutron production relevant to shielding in space". Radiation Protection Dosimetry. 116 (1–4): 140–143. doi:10.1093/rpd/nci033. PMID 16604615.