Florent Schmitt: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

In 1927 he was one of the ten French composers who each contributed a dance for the children's ballet ''[[L'éventail de Jeanne]]'': he wrote the finale, a ''Kermesse-Valse''. |

In 1927 he was one of the ten French composers who each contributed a dance for the children's ballet ''[[L'éventail de Jeanne]]'': he wrote the finale, a ''Kermesse-Valse''. |

||

Other works include the suite for orchestra "Oriane et le Prince d'Amour" op. 83 bis (1934), the symphonic diptych to the memory of Gabriel Faure "In Memoriam" op. 72 (1937), the "Ronde Buelesque" op. 78 (1927), the "Legende pour alto et orchestre" op. 66 (1918), the orchestral fresco "Anthony and Cleopatra" |

Other works include the suite for orchestra "Oriane et le Prince d'Amour" op. 83 bis (1934), the symphonic diptych to the memory of Gabriel Faure "In Memoriam" op. 72 (1937), the "Ronde Buelesque" op. 78 (1927), the "Legende pour alto et orchestre" op. 66 (1918), the orchestral fresco "Anthony and Cleopatra" (1920). |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 05:41, 13 July 2014

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2008) |

Florent Schmitt | |

|---|---|

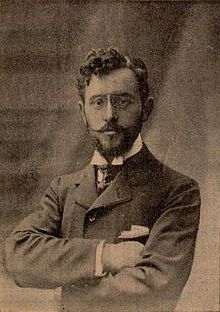

Florent Schmitt in 1900 | |

| Born | 28 September 1870 Meurthe-et-Moselle, France |

| Died | 17 August 1958 |

| Nationality | French |

| Citizenship | |

Florent Schmitt (28 September 1870 – 17 August 1958) was a French composer.

Biography

Early life

A Lorrainer, born in Meurthe-et-Moselle, Schmitt originally took music lessons in Nancy with the local composer Gustave Sandré. Subsequently (at the age of 19) he entered the Paris Conservatoire. There he studied with Gabriel Fauré, Jules Massenet, Théodore Dubois, and Albert Lavignac. In 1900 he won the Prix de Rome.

From 1929 to 1939 Schmitt worked as a music critic for Le Temps, in which role he created considerable controversy, not least for his indiscreet habit of shouting out verdicts from his seat in the hall. The music publisher Heugel went so far as to call him "an irresponsible lunatic".[1]

Later life

Having been one of the most often performed of French composers during the first four decades of the 20th century, Schmitt afterwards fell into comparative neglect, although he continued writing music till the end (and in 1952 he became a member of the Légion d'honneur). He became the subject of attacks — both in his last years and posthumously — over his pro-German sympathies during the 1930s, and over his willingness to work for the Vichy regime later on (as indeed other eminent French musicians did, notably Alfred Cortot and Joseph Canteloube).

He died in Neuilly-sur-Seine in 1958, aged 87.

The 1990s and 2000s witnessed a revival of his output, and an increased coverage of it on compact disc. Beginning in late 2012, the Invencia Piano Duo (Andrey Kasparov and Oksana Lutsyshyn), in collaboration with Naxos Records, on its Grand Piano series, released four CDs of Schmitt's complete duo-piano works.[2][3][4]

Volume 1 contains Schmitt’s Trois rapsodies, Op. 53, and a first-ever recording of Schmitt’s Sept pièces, Op. 15, composed in 1899. The album concludes with a previously unpublished work, Rhapsodie parisienne.[2] Composed in 1900, it is one of two unpublished duets by Schmitt. Special permission to record Rhapsodie parisienne was granted by Mme. Annie Schmitt, granddaughter of Florent.[2]

Works

Schmitt wrote 138 works with opus numbers. He composed examples of most of the major forms of music, except for opera. Today his most famous pieces are La tragédie de Salome and Psaume XLVII (Psalm 47). His piano quintet in B minor, written in 1908, helped establish his reputation. Other works include a violin sonata (Sonate Libre), a late string quartet, a saxophone quartet,[5] Dionysiaques for wind band, and two symphonies. He was part of the group known as Les Apaches. His own style, recognizably impressionistic, owed something to the example of Debussy, though it had distinct traces of Wagner and Richard Strauss also.

Schmitt composed a ballet La tragédie de Salomé in 1907 as a commission from Jacques Rouché for Loie Fuller and the Théâtre des Arts. From the original ballet score, scored for twenty instruments and lasting about an hour, Schmitt prepared a symphonic poem of the same name, half as long as the ballet score, for a much expanded orchestra. The symphonic poem version is much better-known (with recordings conducted by Schmitt himself, Paul Paray, Jean Martinon, Antonio de Almeida, Marek Janowski and others), but there is also an excellent recording of the 1907 ballet score under Patrick Davin on the Marco Polo label. The rhythmic syncopations, polyrhythms, percussively treated chords, bitonality, and scoring of Schmitt's work anticipate Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring. While composing The Rite of Spring, Stravinsky acknowledged that Schmitt's ballet gave him greater joy than any work he had heard in a long time, but they fell out with each other in later years, and Stravinsky reversed his opinion of Schmitt's works.

In 1927 he was one of the ten French composers who each contributed a dance for the children's ballet L'éventail de Jeanne: he wrote the finale, a Kermesse-Valse.

Other works include the suite for orchestra "Oriane et le Prince d'Amour" op. 83 bis (1934), the symphonic diptych to the memory of Gabriel Faure "In Memoriam" op. 72 (1937), the "Ronde Buelesque" op. 78 (1927), the "Legende pour alto et orchestre" op. 66 (1918), the orchestral fresco "Anthony and Cleopatra" (1920).

References

- ^ Leslie De'Ath. "Florent Schmitt in Oxford Music Online for a full biography and list of works". Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ a b c Nones, Phillip (2012-09-13). "Get ready for Florent Schmitt's duo-piano repertoire … all four CDs' worth!". Florentschmitt.com. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ^ Old Dominion University (2012-09-13). "Inside ODU | CD by ODU's Invencia Piano Duo Highlights Works of French Composer". Blue.odu.edu. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ^ Old Dominion University (2013-04-29). "Inside ODU | ODU Invencia Piano Duo Recording Praised in International Reviews". Blue.odu.edu. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ^ "Florent Schmitt", in Sax, Mule & Co, Jean-Pierre Thiollet, Paris: H & D, 2004, pp. 175-176