Waterworld: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

| language = English |

| language = English |

||

| budget = $172 million<ref name="NY Times"/> |

| budget = $172 million<ref name="NY Times"/> |

||

| gross = $264 |

| gross = $264 million<ref name="mojo"/> |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''''Waterworld''''' is a 1995 American [[Apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction|post-apocalyptic]] [[Science fiction film|science fiction]] [[action film]] directed by [[Kevin Reynolds (director)|Kevin Reynolds]] and co-written by Peter Rader and [[David Twohy]]. It was based on Rader's original 1986 screenplay and stars [[Kevin Costner]], who also [[Film producer|produced]] it with Charles Gordon and John Davis. It was distributed by [[Universal Pictures]]. |

'''''Waterworld''''' is a 1995 American [[Apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction|post-apocalyptic]] [[Science fiction film|science fiction]] [[action film]] directed by [[Kevin Reynolds (director)|Kevin Reynolds]] and co-written by Peter Rader and [[David Twohy]]. It was based on Rader's original 1986 screenplay and stars [[Kevin Costner]], who also [[Film producer|produced]] it with Charles Gordon and John Davis. It was distributed by [[Universal Pictures]]. |

||

Revision as of 17:12, 22 October 2014

| Waterworld | |

|---|---|

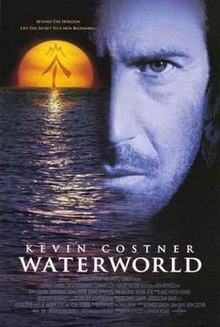

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Kevin Reynolds |

| Written by | Peter Rader David Twohy |

| Produced by | Kevin Costner John Davis Charles Gordon Lawrence Gordon |

| Starring | Kevin Costner Dennis Hopper Jeanne Tripplehorn Tina Majorino Michael Jeter |

| Cinematography | Dean Semler |

| Edited by | Peter Boyle |

| Music by | James Newton Howard |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 135 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $172 million[2] |

| Box office | $264 million[3] |

Waterworld is a 1995 American post-apocalyptic science fiction action film directed by Kevin Reynolds and co-written by Peter Rader and David Twohy. It was based on Rader's original 1986 screenplay and stars Kevin Costner, who also produced it with Charles Gordon and John Davis. It was distributed by Universal Pictures.

The setting of the film is in the distant future. Although no exact date was given in the film itself, it has been suggested that it takes place in 2500.[4] The polar ice caps have completely melted, and the sea level has risen many hundreds of feet, covering nearly all the land. The film illustrates this with an unusual variation on the Universal logo, which begins with the usual image of Earth, but shows the planet's water levels gradually rising and the polar ice caps melting until nearly all the land is submerged. The plot of the film centers on an otherwise nameless antihero, "The Mariner", a drifter who sails the Earth in his trimaran.

The most expensive film ever made at the time, Waterworld was released to mixed reviews, praising the futuristic style but criticizing the characterization and acting performances. The film also was unable to recoup its massive budget at the box office; however, the production did later break even due to video and other post-cinema sales. The film's release was accompanied by a tie-in novel, video game, and three themed attractions at Universal Studios Hollywood, Universal Studios Singapore, and Universal Studios Japan called Waterworld: A Live Sea War Spectacular, which are all still running as of 2014.

Plot

In the beginning of the 21st century the polar ice caps melted and the sea level rose to cover every continent on Earth. Surviving humans were scattered across the ocean on ramshackle floating communities known as atolls, mostly built from scrap metal and decrepit sea vessels. Far in the future, although land-based societies had been eventually forgotten, many still cling to belief in a mythical "Dryland".

A drifter, known only as "the Mariner", arrives at an atoll seeking to trade dirt, which is a precious commodity. When the mariner is revealed to be a mutant with webbed feet and gills who is able to breathe underwater, the fearful atollers vote to drown him in a brine pool they maintain for composting. As they begin lowering the Mariner into the sludge, local pirates known as "Smokers" raid the atoll. The Smokers are searching for an orphan girl named Enola, who has a map to Dryland tattooed on her back. The leader of the smokers is "the Deacon", who wants the map so he can be the first to claim Dryland and build a city upon it.

Enola and her guardian, Helen, had planned to leave the floating city with Gregor, an inventor. However, Gregor accidentally launches the gas balloon they planned to escape in with only himself on board. Helen rescues the Mariner from drowning in the sludge, and he agrees to help them escape on his trimaran.

They encounter the Smokers again, but Helen's naïve actions result in damage to the Mariner's boat, and he angrily cuts their hair to use to splice the ship's ropes back together. Helen is convinced that Dryland exists and demands to know where the Mariner finds his dirt. The Mariner puts her in a diving bell and swims her down to the ruins of Denver where he collects dirt from the bottom of the sea. Helen then realizes that former human civilization existed on land, and had not always lived on water.

When they surface, the Mariner and Helen are captured by the Smokers and used to flush Enola from hiding. They dive overboard, barely escaping. Since Helen cannot breathe underwater, the Mariner uses his gills to breathe for the both of them. They resurface and find everyone gone and the trimaran destroyed. They are rescued by Gregor in his balloon and taken to a new makeshift atoll where the survivors of the first atoll attack have regrouped.

Using a captured Smoker jet ski, the Mariner chases down the Deacon, finding him on the remaining hulk of the Exxon Valdez. The Deacon is celebrating with the huge Smoker crew, proclaiming they have found the map to Dryland. After the crew have all gone below decks to row the ship, the Mariner walks out onto the deck, where the Deacon and his top men are examining Enola's tattoo. He threatens to drop a flare into the oil reserve tank unless the Deacon releases Enola. The Deacon refuses, so the Mariner ignites and drops the flare. The ship explodes below-decks and begins sinking while the Mariner escapes with Enola by climbing a rope up to Gregor's balloon.

The Deacon makes a grab for Enola, but Helen throws a bottle at him, causing him to fall. He pulls out his pistol and shoots one of the balloon's lines, causing Enola to fall into the sea. The Deacon mounts a jet ski and signals two other jet skiing Smokers to converge on Enola. The Mariner, seeing this, ties a rope around his ankle and jumps down to grab Enola. The recoil of the cord pulls them to safety just as the jet skis collide and explode, killing the Deacon.

Gregor deciphers the Asian symbols on the map using an old China Airlines magazine. He realizes that they are coordinates and steers his balloon in that direction. They find Dryland, the top of Mount Everest, which is now verdant and welcoming with fresh water, forests, and wildlife. Gregor, Enola, Helen and other atoll survivors land and find the remains of Enola's parents in a hut. They prepare to settle, but the Mariner decides he must leave as the ocean, his only home, calls to him.

Cast

- Kevin Costner as The Mariner

- Dennis Hopper as The Deacon

- Jeanne Tripplehorn as Helen

- Tina Majorino as Enola

- Michael Jeter as Old Gregor

- Jack Black as Smoker Plane Pilot

- Kim Coates as Drifter #2

- Robert Joy as Smoker Ledger Guy

- Robert LaSardo as Smitty

- Gerard Murphy as The Nord

- R. D. Call as Atoll Enforcer

- John Fleck as Smoker Doctor

- John Toles-Bey as Smoker Plane Gunner (Ed)

- Zakes Mokae as Priam

- Sab Shimono, Leonardo Cimino, and Zitto Kazann as Atoll Elders

- Rick Aviles as Atoll Gatesman #1

- Jack Kehler as Atoll Banker

- Chris Douridas as Atoller #7

- Robert A. Silverman as Hydroholic

- Neil Giuntoli as Hellfire Gunner (Chuck)

- William Preston as Smoker Depth Gauge Guy

- Sean Whalen as Bone

- Lee Arenberg as Djeng

Production

The film marked the fourth collaboration between Costner and Reynolds, who had previously worked together on Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991), Fandango (1985), and Rapa Nui (1994), the latter of which Costner coproduced but did not star in.[5] Waterworld was cowritten by David Twohy, who cited Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior as a major inspiration. Both films employed Dean Semler as director of photography. Gene Hackman, James Caan, Laurence Fishburne, and Gary Oldman all turned down the role of the Deacon.[citation needed] Anna Paquin was the first choice to play Enola.[citation needed]

During production, the film was plagued by a series of cost overruns and production setbacks. Universal initially authorized a budget of $100 million, but production costs eventually ran to an estimated $175 million, a record sum for a film production at the time. Filming took place in a large artificial seawater enclosure similar to that used in the film Titanic two years later; it was located in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Hawaii. The final scene was filmed in Waipio Valley on the Big Island, also referred to as The Valley of Kings. The production was hampered by the collapse of the multi-million dollar set during a hurricane. Additional filming took place in Los Angeles, Huntington Beach, and Santa Catalina Island, and the Channel Islands of California.

The production featured different types of personal watercraft (PWC), especially Kawasaki jet skis. Kevin Costner was on the set for 157 days, working 6 days a week.[6] At one point, he nearly died when he got caught in a squall while tied to the mast of his trimaran.[7] Laird Hamilton, the well-known surfer, was Kevin Costner’s stunt double for many water scenes. Hamilton, who commuted to the set via jet ski, was temporarily lost at sea when his jet ski ran out of fuel between Maui and the Big Island. He drifted for hours before being spotted by a Coast Guard plane and rescued.[citation needed] When the abandoned jet ski washed up on shore on the island of Lanai, he retrieved it and drove it home. Stunt coordinator Norman Howell suffered from decompression sickness while filming an underwater scene and was rushed to a hospital in Honolulu by helicopter. He recovered quickly from the potentially life-threatening sickness and returned to the set two days later.[citation needed] Tina Majorino was nicknamed "Jellyfish Candy" by Costner after she was stung by jellyfish on three occasions during production.[citation needed]

Mark Isham's score, which was not recorded and only demos were completed for approximately 25% of the film, was reportedly rejected by Costner because it was "too ethnic and bleak", contrasting the film's futuristic and adventurous tone; Isham offered to try again, but was not given the chance.[8] James Newton Howard was brought in to write the new score. Joss Whedon flew out to the set to do last minute script rewrites and later described it as "seven weeks of hell"; the work boiled down to editing in Costner's ideas without alteration.[9][10]

The state of Hawaii had more than $35 million added to its economy as a result of the colossal film production.[11] Rumors abound that, after the filming ran notoriously over-budget, Kevin Costner fired Kevin Reynolds as director and shot the last few scenes himself.[citation needed] Other rumors suggest Reynolds was not fired, but simply walked off set with two weeks of filming left.[citation needed] Despite their reported clashes, the director and star reunited almost two decades later for the History Channel miniseries Hatfields & McCoys.

Inspired by racing trimarans built by Jeanneau Advanced Technologies' multi-hull division Lagoon; a custom 60 foot (18 m) yacht was designed by Marc Van Peteghem and Vincent Lauriot-Prevost and built in France by Lagoon. Two versions were built, a relatively standard racing trimaran for distance shots, and an effects-laden transforming trimaran for closeup shots. The first trimaran was launched on 2 April 1994, and surpassed 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph) in September of that year.[12] The transforming version was first seen in the film as a sort of raft with a three-bladed egg-beater windmill. When needed, levers could be triggered that would flatten the windmill blades while raising a hidden mast to full racing height. A boom emerged, previously hidden in the hull, and the two sails were automatically unfurled. Once the transformation was complete this version could actually sail, although not as well as the dedicated racer.[12] The transforming version is in private hands in San Diego, California.[12] For many years, the racing version was kept in a lake at Universal Studios Florida,[12] before being restored for use as a racing trimaran named Loe Real, which was (as of 2012) being offered for sale in San Diego.[13]

Release

Box office

Due to the runaway costs of the production and its expensive price tag, some critics dubbed it "Fishtar"[14] and "Kevin's Gate",[15] alluding to the flops Ishtar and Heaven's Gate, although the film debuted at the box office at #1.[16][17] With a budget of $172 million (not including marketing and distribution costs for a total outlay of $235 million),[2] the film grossed $88 million at the North American box office. The film did better overseas, with $176 million at the foreign box office, for a worldwide total of $264 million.[3] However, even though this figure surpasses the total costs spent by the studio, it does not take into account the percentage of box office gross that theaters retain, which is generally up to half;[2] but after factoring in home video sales and TV broadcast rights among other revenue streams, Waterworld eventually broke even.[18]

Critical reception

Contemporary reviews for the film were mostly mixed. Roger Ebert said of Waterworld: "The cost controversy aside, Waterworld is a decent futuristic action picture with some great sets, some intriguing ideas, and a few images that will stay with me. It could have been more, it could have been better, and it could have made me care about the characters. It's one of those marginal pictures you're not unhappy to have seen, but can't quite recommend."[19] James Berardinelli of Reelviews Movie Reviews was one of the film's few supporters calling it "one of Hollywood's most lavish features to date". He wrote: "Although the storyline isn't all that invigorating, the action is, and that's what saves Waterworld. In the tradition of the old Westerns and Mel Gibson's Mad Max flicks, this film provides good escapist fun. Everyone behind the scenes did their part with aplomb, and the result is a feast for the eyes and ears."[20]

Metacritic gives the film a score of 56%, based on reviews from 17 critics, in the range of "Mixed or average reviews".[21] Rotten Tomatoes gives a score of 43% based on reviews from 49 critics, with and an average rating of 5.1, and site's critical consensus being "Though it suffered from toxic buzz at the time of its release, Waterworld is ultimately an ambitious misfire: an extravagant sci-fi flick with some decent moments and a lot of silly ones."[22]

Home media

Waterworld was released on DVD on November 1, 1998.

Awards and nominations

| Award | Subject | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[23] | Best Sound Mixing | Steve Maslow, Gregg Landaker and Keith A. Wester | Nominated |

| Saturn Awards | Best Science Fiction Film | Nominated | |

| Best Costumes | John Bloomfield | Nominated | |

| BAFTA Film Awards | Best Visual Effects | Michael J. McAlister, Brad Kuehn, Robert Spurlock and Martin Bresin | Nominated |

| Golden Raspberry Awards | Worst Picture | Nominated | |

| Worst Actor | Kevin Costner | Nominated | |

| Worst Director | Kevin Reynolds | Nominated | |

| Worst Supporting Actor | Dennis Hopper | Won |

Legacy

The film was repackaged in a number of forms, including a 1995 Gottlieb Amusements (later Premier, both now defunct) pinball machine.[24]

Video games

Video games based on the film were released for the Super Nintendo, Game Boy, Virtual Boy, and PC. There was to be a release for the Sega Genesis, but it was canceled and was only available on the Sega Channel. A Sega Saturn version of the game was also planned and development was completed but like its Genesis counterpart it was also cancelled prior to release. The Super Nintendo and Game Boy releases were only available in the United Kingdom and Australia. While the Super Nintendo and Virtual Boy versions were released by Ocean Software, the PC version was released by Interplay. The game received negative reviews; the Virtual Boy version was marked as the worst Virtual Boy game ever released out of the 22 games produced for it.[according to whom?]

Novel

A tie-in novel was written by Max Allan Collins and published by Arrow Books. The novel goes into greater detail regarding the world of the film.

Comic books

A sequel comic book four-issue mini-series entitled Waterworld: Children of Leviathan was released by Acclaim Comics in 1997. Kevin Costner did not permit his likeness to be used for the comics, so the Mariner looks different. The story reveals some of the Mariner's back-story as he gathers clues about where he came from and why he is different. The comic expands on the possible cause of the melting of the polar ice caps and worldwide flood, and introduces a new villain, "Leviathan", who supplied the Deacon's Smoker organization. The comic hints at the possibility that the Mariner's mutation may not be caused by evolution but by genetic engineering and that his origins may be linked to those of the "Sea Eater", the sea monster seen during the fishing scene in the film.

Theme park attractions

There are attractions at Universal Studios Hollywood, Universal Studios Japan, and Universal Studios Singapore based on the film. The show's plot takes place immediately after the movie, as Helen returns to the Atoll with proof of Dryland, only to find herself followed by the Deacon, who survived the events of the movie. The Mariner arrives immediately after him, defeats the Deacon and takes Helen back to Dryland while the Atoll explodes.

References

- ^ "WATERWORLD (12)". British Board of Film Classification. 1995-07-26. Retrieved 2012-05-24.

- ^ a b c Weinraub, Bernard (July 31, 2010). "'Waterworld' Disappointment As Box Office Receipts Lag". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 24, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Waterworld (1995)". Box Office Mojo. 1995-09-26. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ The Making of Waterworld by Janine Pourroy (August 1995). Production designer Dennis Gassner states: "The date was 2500."

- ^ Eller, Claudia; Welkos, Robert W. (1994-09-16). "Plenty of Riptides on 'Waterworld' Set : With key crew people quitting and reported turmoil, logistical and organizational problems, the big-budget film, scheduled for release in summer of '95, could end up costing more than any movie ever made". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2012-06-13.

- ^ "Stashed Chats: Kevin Costner talks "Draft Day"". thestashed.com. 2014-04-10. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- ^ "Kevin Costner's Hawaii Uh-Oh". people.com. 1995-05-29. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- ^ "Waterworld (James Newton Howard)". Filmtracks. 1995-08-01. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ "Waterworld and troubles for Blu-ray?". Mania.com. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ Robinson, Tasha (September 5, 2001). "Joss Whedon". The A.V. Club. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ^ "The Most Expensive Movies Ever Made". Forbes.com. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ a b c d "The Mariner's Trimaran". October 27, 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-10-27.

- ^ ""Loe Real" - 60' Jeanneau Custom Trimaran". Morrelli & Melvin. 2012.

- ^ "Waterworld (PG-13)". The Washington Post. 1995-07-28.

- ^ "Married with Movies: Waterworld - Two-Disc Extended Edition". Archived from the original on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 2013-07-16.

- ^ Natale, Richard (1995-07-31). "Waterworld Sails to No. 1 : Movies: The $175-million production takes in $21.6 million in its first weekend. But unless it enlarges its appeal, it will probably gross about half its cost". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- ^ Eyerly, Alan (1995-07-31). "Strong Opening Weekend for 'Waterworld': Fans: Why do people endure epic waits in line to see big movies? It's, like, a party". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- ^ Fleming Jr., Mike (August 7, 2013). "Isn't It Time To Take 'Waterworld' Off The All-Time Flop List?". Deadline.com. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 28, 1995). "Waterworld". The Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Berardinelli, James. "Waterworld". Reelviews. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

- ^ "Waterworld Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 2013-06-10.

- ^ "Waterworld (1995)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved 2013-06-10.

- ^ "The 68th Academy Awards (1996) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ^ "Internet Pinball Machine Database: Premier 'Waterworld'". Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- Parish, James Robert (2006). Fiasco - A History of Hollywood’s Iconic Flops. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-69159-4. 359 pages

External links

- 1995 films

- 1990s action films

- 1990s science fiction films

- American films

- American science fiction action films

- English-language films

- Screenplays by Joss Whedon

- Fictional-language films

- Films directed by Kevin Reynolds

- Films set in the future

- Post-apocalyptic films

- Seafaring films

- Davis Entertainment films

- Universal Pictures films

- Climate change films

- Films shot in Hawaii

- Film scores by James Newton Howard

- Flood films