Chameria: Difference between revisions

Adding in Baltsiotis source for term usage and it being associated with Chams. |

→Middle Ages: To quote exactly the source and leave conclusions to the reader. |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

===Middle Ages=== |

===Middle Ages=== |

||

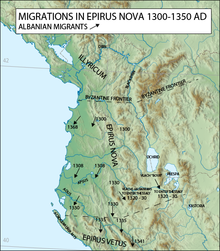

[[File:13001350ALBANIANMIGRATIONS.png|thumb|Population movements in Epirus during the 14th century]] |

[[File:13001350ALBANIANMIGRATIONS.png|thumb|Population movements in Epirus during the 14th century]] |

||

In Medieval Ages the region was under the jurisdiction of the [[Roman Empire|Roman]] and later [[Byzantine Empire]]. In 1205, [[Michael I Komnenos Doukas|Michael Komnenos Doukas]], a cousin of the [[Byzantine emperor]]s [[Isaac II Angelos]] and [[Alexios III Angelos]], founded the [[Despotate of Epiros]], which ruled the region until the 15th century. Vagenetia as the whole of Epirus soon became the new home of many Greek [[refugee]]s from [[Constantinople]], [[Thessaly]], and the [[Peloponnese]], and Michael was described as a second [[Noah]], rescuing men from the [[Latin Empire|Latin]] flood. During this time, the earliest mention of Albanians within the region of Epirus is recorded in a Venetian document of 1210 as inhabiting the area opposite the island of Corfu.<ref name=Giakoumis/> |

In Medieval Ages the region was under the jurisdiction of the [[Roman Empire|Roman]] and later [[Byzantine Empire]]. In 1205, [[Michael I Komnenos Doukas|Michael Komnenos Doukas]], a cousin of the [[Byzantine emperor]]s [[Isaac II Angelos]] and [[Alexios III Angelos]], founded the [[Despotate of Epiros]], which ruled the region until the 15th century. Vagenetia as the whole of Epirus soon became the new home of many Greek [[refugee]]s from [[Constantinople]], [[Thessaly]], and the [[Peloponnese]], and Michael was described as a second [[Noah]], rescuing men from the [[Latin Empire|Latin]] flood. During this time, the earliest mention of Albanians within the region of Epirus is recorded in a Venetian document of 1210 as inhabiting the area opposite the island of Corfu.<ref name=Giakoumis/> The first appearance of Albanians "en masse" in the Despotate of Epirus is not recorded before 1337. However, byzantine sources present Albanians as nomads.<ref name=Giakoumis>Giakoumis, Konstantinos (2003), p. 177"[http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kosta_Giakoumis/publication/233673710_Fourteenth-century_Albanian_migration_and_the_relative_autochthony_of_the_Albanians_in_Epeiros._The_case_of_Gjirokaster/links/0deec52ab0987b856e000000.pdf Fourteenth-century Albanian migration and the ‘relative autochthony’ of the Albanians in Epeiros. The case of Gjirokastër.]" ''Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies''. '''27'''. (1): 176. "The presence of Albanians in the Epeirote lands from the beginning of the thirteenth century is also attested by two documentary sources: the first is a Venetian document of 1210, which states that the continent facing the island of Corfu is inhabited by Albanians; and the second is letters of the Metropolitan of Naupaktos John Apokaukos to a certain George Dysipati, who was considered to be an ancestor of the famous Shpata family."; </ref> |

||

In the 1340s, taking advantage of a [[Byzantine civil war of 1341–1347|Byzantine civil war]], the [[Medieval Serbia|Serbian]] King [[Stefan Uroš IV Dušan]] conquered Epirus and incorporated it in his [[Serbian Empire]].<ref>{{cite book|author=John Van Antwerp Fine|title=The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest|publisher=University of Michigan Press|year=1994|isbn=978-0-472-08260-5|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Hh0Bu8C66TsC|page=320}}</ref> During this time, two Albanian states were formed in the region. In the summer of 1358, [[Nikephoros II Orsini]], the last [[Despotate of Epirus|despot of Epirus]] of the Orsini dynasty, was defeated in battle against Albanian chieftains. Following the approval of the Serbian Tsar, these chieftains established two new states in the region, the [[Despotate of Arta]] and [[Principality of Gjirokastër]].<ref>{{cite book|author=John Van Antwerp Fine|title=The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest|publisher=University of Michigan Press|year=1994|isbn=978-0-472-08260-5|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Hh0Bu8C66TsC|pages=349–350}}</ref> Internal dissension and successive conflicts with their neighbours, including the rising power of the [[Ottoman Turks]], led to the downfall of these Albanian principalities to the [[Tocco family]]. The Tocco in turn gradually gave way to the Ottomans, who took [[Ioannina]] in 1430, [[Arta, Greece|Arta]] in 1449, [[Angelokastro (Aetolia-Acarnania)|Angelokastron]] in 1460, and finally [[Vonitsa]] in 1479.<ref>{{cite book|author=John Van Antwerp Fine|title=The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest|publisher=University of Michigan Press|year=1994|isbn=978-0-472-08260-5|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Hh0Bu8C66TsC|pages=350–357, 544, 563}}</ref> |

In the 1340s, taking advantage of a [[Byzantine civil war of 1341–1347|Byzantine civil war]], the [[Medieval Serbia|Serbian]] King [[Stefan Uroš IV Dušan]] conquered Epirus and incorporated it in his [[Serbian Empire]].<ref>{{cite book|author=John Van Antwerp Fine|title=The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest|publisher=University of Michigan Press|year=1994|isbn=978-0-472-08260-5|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Hh0Bu8C66TsC|page=320}}</ref> During this time, two Albanian states were formed in the region. In the summer of 1358, [[Nikephoros II Orsini]], the last [[Despotate of Epirus|despot of Epirus]] of the Orsini dynasty, was defeated in battle against Albanian chieftains. Following the approval of the Serbian Tsar, these chieftains established two new states in the region, the [[Despotate of Arta]] and [[Principality of Gjirokastër]].<ref>{{cite book|author=John Van Antwerp Fine|title=The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest|publisher=University of Michigan Press|year=1994|isbn=978-0-472-08260-5|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Hh0Bu8C66TsC|pages=349–350}}</ref> Internal dissension and successive conflicts with their neighbours, including the rising power of the [[Ottoman Turks]], led to the downfall of these Albanian principalities to the [[Tocco family]]. The Tocco in turn gradually gave way to the Ottomans, who took [[Ioannina]] in 1430, [[Arta, Greece|Arta]] in 1449, [[Angelokastro (Aetolia-Acarnania)|Angelokastron]] in 1460, and finally [[Vonitsa]] in 1479.<ref>{{cite book|author=John Van Antwerp Fine|title=The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest|publisher=University of Michigan Press|year=1994|isbn=978-0-472-08260-5|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Hh0Bu8C66TsC|pages=350–357, 544, 563}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 12:00, 23 October 2015

Chameria (Albanian: Çamëria, Greek: Τσαμουριά Tsamouriá) is a term used today mostly by Albanians for parts of the coastal region of Epirus in southern Albania and northwestern Greece traditionally associated with an Albanian speaking population called Chams.[1] Apart from geographical usages, in contemporary times within Albania the toponym has also acquired irredentist connotations.[2][3] Today it is obsolete in Greek, surviving in some old folk songs,[citation needed]. Most of what is called Chameria is divided between the Greek regional units of Thesprotia and Preveza, the southern extremity of Albania's Sarandë District and some villages in eastern Ioannina regional unit. As the Greek toponyms Epirus and Thesprotia have been established for the region since antiquity, and given the negative sentiments towards Albanian irredentism, the term is not used by the locals on the Greek side of the border.

Name and definition

Etymology

Chameria was mostly used as a term for the region of modern Thesprotia, during the Ottoman rule.[4][5] It is of uncertain etymology. It possibly derives from the ancient Greek name of the Thyamis river, which in the Albanian language is called Cham (Çam), through the unattested slavic *čamь or *čama rendering the older slavic *tjama.[6]

Boundaries

The region of Chameria overlaps to a high degree with the ancient and modern region of Thesprotia and the medieval region known as Vagenetia, lying north of Ambracian Gulf and west of the Pindus mountains.[7] The northern boundary of the region is not precisely defined: in Antiquity, the northern boundary of Thesprotia was the Thyamis river,[7] but in the Middle Ages, the presumed borders were pushed to the north. Vagenetia included today's Sarandë District and Delvinë District of Southern Albania, bordering with the Llogara and Muzina mountains in the north and northeast.

In modern times, the region of Chameria was reduced to the dialectological territory of the Chams, stretching between the mouth of the Acheron river in the south, the area of Butrint in the north, and the Pindus in the east.[8] After the permanent demarcation of the Greco-Albanian border, only two small municipalities were left in southern Albania (Markat and Konispol), while the remainder of the territory fell under the Greek prefectures of Thesprotia (a name revived by the Metaxas Regime in 1936) and Preveza, with a few villages in Ioannina Prefecture.[citation needed]

Pre-War Greek sources say that Chamerian coast extentds from Acheron River to Buthroton (Butrint) and the inland reaches east till the slopes of the Mount Olytsikas (or Tomaros). The center of Chameria is considered to be Paramythia and other areas are Philiati, Parga and Margariti.[9]

Geography and climate

The region is mostly mountainous, with valleys and hills concentrated in the southern part, while farmlands are in northern part. Most of them with gridded roads and ditches are within the valleys in the central, southern and the western part. There are five rivers in the region, namely Pavllo in the north, Acheron, Louros Arachthos and Thyamis. Four of them are in Greece, with only the first in Albania.

History

Mycenean Period

Late Mycenean sites have been found in the following areas of Chameria:[10]

- Nekromanteion (Oracle) of Acheron

- Ephyra (Kichyro)

- Dragani

- Paramythia

- Giannioti

Iron Age to Roman period

There are numerous archeological sites from Iron Age (10th to 7th centuries) onwards. In Thesprotia, which can be considered the centre of Chameria, excavations have brought to light finds of this period in the Kokytos valley.[11] The Nekromanteion of Acheron is probably the most important site of the area in antiquity, mentioned already in Homer. Archaeological findinds indicate that a sancturary existed there by 7th century BC. It seems that it ceased to function as an oracle in Roman period.[12] Other important settlements are Ephyra, Buthrotum, the Cheimerion (5 km west of Ephyra), Photike (some identify it with Paramythia), the port of Sybota, the city of Thesprotia, the port city of Elea (in the region of Thesprotia) which is believed to be a Corinthian colony, Pandosia, a colony of Elis, Tarone, near the mouth of river Thyamis, and others, depending on the definition of Chameria.[13]

Middle Ages

In Medieval Ages the region was under the jurisdiction of the Roman and later Byzantine Empire. In 1205, Michael Komnenos Doukas, a cousin of the Byzantine emperors Isaac II Angelos and Alexios III Angelos, founded the Despotate of Epiros, which ruled the region until the 15th century. Vagenetia as the whole of Epirus soon became the new home of many Greek refugees from Constantinople, Thessaly, and the Peloponnese, and Michael was described as a second Noah, rescuing men from the Latin flood. During this time, the earliest mention of Albanians within the region of Epirus is recorded in a Venetian document of 1210 as inhabiting the area opposite the island of Corfu.[14] The first appearance of Albanians "en masse" in the Despotate of Epirus is not recorded before 1337. However, byzantine sources present Albanians as nomads.[14]

In the 1340s, taking advantage of a Byzantine civil war, the Serbian King Stefan Uroš IV Dušan conquered Epirus and incorporated it in his Serbian Empire.[15] During this time, two Albanian states were formed in the region. In the summer of 1358, Nikephoros II Orsini, the last despot of Epirus of the Orsini dynasty, was defeated in battle against Albanian chieftains. Following the approval of the Serbian Tsar, these chieftains established two new states in the region, the Despotate of Arta and Principality of Gjirokastër.[16] Internal dissension and successive conflicts with their neighbours, including the rising power of the Ottoman Turks, led to the downfall of these Albanian principalities to the Tocco family. The Tocco in turn gradually gave way to the Ottomans, who took Ioannina in 1430, Arta in 1449, Angelokastron in 1460, and finally Vonitsa in 1479.[17]

Ottoman rule

During the Ottoman rule, the region was under the Vilayet of Ioannina, and later under the Pashalik of Yanina. During this time, the region was known as Chameria (also spelled Tsamouria, Tzamouria) and became a district in the Vilayet of Yanina.[4][18]

In the 18th century, as the power of the Ottomans declined, the region came under the semi-independent state of Ali Pasha Tepelena, an Albanian brigand who became the provincial governor of Ioannina in 1788. Ali Pasha started campaigns to subjugate the confederation of the Souli settlements in this region. His forces met fierce resistance by the Souliotes warriors. After numerous failed attempts to defeat the Souliotes, his troops succeeded in conquering the area in 1803.[19]

After the fall of the Pashalik, the region remained under the control of the Ottoman Empire, while Greece and Albania declared that their goal was to include in their states the whole region of Epirus, including Thesprotia or Chameria.[20] Finally, following the Balkan Wars, Epirus was divided in 1913, in the London Peace Conference, and the region came under the control of Kingdom of Greece, with only a small portion being integrated into the newly formed State of Albania.[20]

During the Turkish occupation Chameria had a feudal system of administration. The most important and older feudal clan was that of Proniati of Paramythia (Drandakis).

Modern history

When the region came under Greek control in 1913, its population included speakers of Greek, Albanian, Aromanian and Romani.

Muslim Chams were counted as a religious minority, and some of them were transferred to Turkey, during the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey,[21] while their property was alienated by the Greek government as part of the relevant agreement between Greece and Turkey.[22] Orthodox Cham Albanians were counted as Greeks, and their language and Albanian heritage were under pressure of assimilation.[23] The region was then settled by Greek refugees from Asia Minor.[24][need quotation to verify]

In 1930s the population was approximately 70,000, the Muslim Albanian speakers estimated around 18,000–20,000. All the population, independently of religion of ethnicity, were called Chams [25] (According to the 1928 census the total Muslim population in Greece was 126.017[26]).

In 1936 the Ioannina prefecture where the area was included, divided into two parts and the new prefecture took the name Thesprotia which was its ancient name. Cham Albanians were given religious, but no ethnic minority status and there was little evidence of direct state persecution at this time.[27]

During the Axis occupation of Greece (1941–1944), small parts of the Muslim Cham community collaborated with the Italian and German forces committing a number of war crimes.[28] At the end of World War II, nearly all Muslim Chams in Greece were expelled to Albania, because of that activity.[29] However, another part of Muslim Chams provided military support to the resistance forces of the Greek People's Liberation Army, while the rest were civilians uninvolved in the war. Led by Zervas' former officer, Col. Zotos, a loose paramilitary grouping of former guerrillas and local men went on a rampage. In the worst massacre, in the town of Filiates on 13 March, some sixty to seventy Chams were killed.[30]

Demographics

Since the Medieval Ages, the population of the region of Chameria was of mixed and complex ethnicity, with a blurring of group identities such as Albanian and Greek, along with many other ethnic groups. Information on the ethnic composition of the region over several centuries is almost entirely absent, with the strong likelihood that they did not fit into standard "national" patterns, as the 19th-century revolutionary nationalist movements wanted.

Historical

In Greek censuses, only Muslims of the region were counted as Albanians. According to the 1913 Greek census, 25,000 Muslims were living at the time in the Chameria region[23] who had Albanian as their mother tongue, from a total population of about 60,000, while in 1923 there were 20,319 Muslim Chams. In the Greek census of 1928, there were 17,008 Muslims who had it as their mother tongue. During the interwar period, the numbers of Albanian speakers in official Greek censuses varied and fluctuated, due to political motives and manipulation.[31]

The main census that counted Orthodox communities of Albanian ethnicity was undertaken by Italian occupational forces and conducted during World War II (1941). This census found that in the region lived 54,000 Albanians, of whom 26,000 Orthodox and 28,000 Muslim and 20,000 Greeks.[22] After the war, according to Greek censuses where ethno-linguistic groups were counted, Muslim Chams were 113 in 1947 and 127 in 1951. In the same Greek census of 1951, 7,357 Orthodox Albanian-speakers were counted within the whole of Epirus.[32]

| Year | Muslim Chams |

Orthodox Chams |

Total number of Chams |

Total population |

Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1908 | 34,406 | 11,662[33] | 46,068 | 74,844 | Statistics by Amadori Virgili, presented by the pro-Greek "Pan-Epirotic Union of America" for the Paris peace conference.[34]Note that the area represented here does not necessarily exactly match up to the modern provincial boundaries of Thesprotia. |

| 1913 | 25,000 | --- | Unknown | 59,000 | Greek census[23] |

| 1923 | 20,319 | --- | Unknown | 58,780 | Greek census[22] |

| 1925 | 25,000 | 22,000 | 47,000 | 58,000 | Albanian government[22][35] |

| 1928 | 17,008 | --- | Unknown | 68,200 | Greek census[22] |

| 1938 | 17,311 | --- | Unknown | 71,000 | Greek government[22] |

| 1940 | 21,000–22,000 | --- | Unknown | 72,000 | Estimation on Greek census[22] |

| 1941 | 28,000 | 26,000 | 54, 000 | Italian census (undertaken by Axis occupational forces during World War Two)[22] | |

| 1947 | 113 | --- | Unknown | Greek census[22] | |

| 1951 | 127 | --- | Unknown | Greek census.[22] 7,357 Orthodox Albanian-speakers were also counted within the whole of Epirus.[32] |

Current

With the exception of the part of Chameria lying in Albania, Chameria is nowadays inhabited mostly by Greeks as a result of the Cham exodus following World War II and subsequent assimilation of remaining Chams. The number of ethnic Albanians still residing in the Chameria region is uncertain, since the Greek government does not include ethnic and linguistic categories in any official census.

Muslims

The Greek census of 1951 counted a total of 127 Muslim Albanian Chams in Epirus.[36] In more recent years (1986) 44 members of this community are found in Thesprotia, located in the settlements of Sybota, Kodra and Polyneri (previously Koutsi).[37] Moreover, until recently the Muslim community in Polyneri was the only one in Epirus to have an imam.[38] The village mosque was the last within the area before being blown up by a local Christian in 1972.[39] The number of Muslim Chams remaining in the area after World War II included also people who converted to Orthodoxy and were assimilated into the local population in order to preserve their properties and themselves.[40][41][42]

Christian Orthodox

According to a study by the Euromosaic project of the European Union, Albanian speaking communities live along the border with Albania in Thesprotia prefecture, the northern part of the Preveza prefecture in the region called Thesprotiko, and a few villages in Ioannina regional unit.[43] The Arvanite dialect is still spoken by a minority of inhabitants in Igoumenitsa.[44] In northern Preveza prefecture, those communities also include the region of Fanari,[45] in villages such as Ammoudia[46] and Agia.[47] In 1978, some of the older inhabitants in these communities were Albanian monolinguals.[48] The language is spoken by young people too, because when the local working-age population migrate seeking a job in Athens, or abroad, the children are left with their grandparents, thus creating a continuity of speakers.[48]

Today, these Orthodox Albanian speaking communities refer to themselves as Arvanites in the Greek language and self-identify as Greeks, like the Arvanite communities in southern Greece.[49] They refer to their language in Greek as Arvanitika and when conversing in Albanian as Shqip.[50][51] In contrast with the Arvanites, some have retained a distinct linguistic [52] and ethnic identity, but also an Albanian national identity.[53][dubious – discuss] In the presence of foreigners there is a stronger reluctance amongst Orthodox Albanian speakers to speak Albanian, compared to the Arvanites in other parts of Greece.[54] A reluctance has been also noticed for those who still see themselves as Chams to declare themselves as such.[55] Researchers like Tom Winnifirth on short stays in the area have hence found it difficult to find Albanian speakers in urban areas[56] and concluded in later years that Albanian is not longer spoken at all in the region.[57] According to Ethnologue, the Albanian speaking population of Greek Epirus and Greek Western Macedonia number 10, 000.[58]According to the pro-Albanian[59][60] author Miranda Vickers, Orthodox Chams today are approximately 40,000.[61] Amongst some Orthodox Albanian speakers like those in the village of Kastri near Igoumentisa, there has been a revival in folklore, in particular in the performance of "Arvanitic wedding".[62]

See also

References

- ^ Baltsiotis, Lambros (2011). The Muslim Chams of Northwestern Greece: The grounds for the expulsion of a "non-existent" minority community. European Journal of Turkish Studies. "During the beginning of the 20th Century, the northwestern part of the Greek region of Epirus was mostly populated by an Albanian-speaking population, known under the ethnonyme “Chams” [Çamë, Çam (singular)in Albanian, Τσ(ι)άμηδες, Τσ(ι)άμης in Greek]. The Chams are a distinct ethno-cultural group which consisted of two integral religious groups: Orthodox Christians and Sunni Muslims. This group lived in a geographically wide area, expanding to the north of what is today the Preveza prefecture, the western part of which is known as Fanari [Frar in Albanian], covering the western part of what is today the prefecture of Thesprotia, and including a relatively small part of the region which today constitutes Albanian territory. These Albanian speaking areas were known under the name Chamouria [Çamëri in Albanian, Τσ(ι)αμουριά or Τσ(ι)άμικο in Greek]."

- ^ Kretsi, Georgia.The Secret Past of the Greek-Albanian Borderlands. Cham Muslim Albanians: Perspectives on a Conflict over Historical Accountability and Current Rights in Ethnologica Balkanica, Vol. 6, p. 172.

- ^ Jahrbücher für Geschichte und Kultur Südosteuropas: JGKS, Volumes 4–5 Slavica Verlag, 2002.

- ^ a b Balkan Studies By Hetaireia Makedonikōn Spoudōn. Hidryma Meletōn Cheresonēsou tou Haimou. Published by Institute for Balkan Studies, Society for Macedonian Studies., 1976

- ^ NGL Hammond, Epirus: The Geography, the Ancient Remains, the History and Topography of Epirus and Adjacent Areas, Published by Clarendon P., 1967, p. 31

- ^ Orel Vladimir, Albanian etymological dictionary, Brill, 1998, pp 49, 50.

- ^ a b An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis: An Investigation Conducted by the Copenhagen Polis Centre for the Danish National Research Foundation By Thomas Heine Nielsen, Københavns universitet Polis, Danish National Research Foundation Published by Oxford University Press, 2004 ISBN 0-19-814099-1, ISBN 978-0-19-814099-3

- ^ Miranda Vickers, The Albanians: A Modern History, I.B.Tauris, 1999, ISBN 978-1-86064-541-9, p. 113

- ^ Drandakis Pavlos (editor), Great Greek Encyclopedia, vol. 23, article Tsamouria. Editions "Pyrsos", 1936–1934, in Greek language.

- ^ Papadopoulos Thanasis J. (1987) Tombs and burial customs in Late Bronze Ages Epirus, pp 137–143, in Thanatos. Plate (map) XXXIV. Scribd.com (2011-01-11). Retrieved on 2014-02-01.

- ^ The Thesprotia Expedition, A Regional, Interdisciplinary Survey Project in Northwestern Greece.

- ^ Nekromanteion of Acheron. Ammoudiarooms.com (2012-11-24). Retrieved on 2014-02-01.

- ^ Mogens Herman Hansen (2004). An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis. OUP Oxford. pp. 502–. ISBN 978-0-19-814099-3.

- ^ a b Giakoumis, Konstantinos (2003), p. 177"Fourteenth-century Albanian migration and the ‘relative autochthony’ of the Albanians in Epeiros. The case of Gjirokastër." Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. 27. (1): 176. "The presence of Albanians in the Epeirote lands from the beginning of the thirteenth century is also attested by two documentary sources: the first is a Venetian document of 1210, which states that the continent facing the island of Corfu is inhabited by Albanians; and the second is letters of the Metropolitan of Naupaktos John Apokaukos to a certain George Dysipati, who was considered to be an ancestor of the famous Shpata family.";

- ^ John Van Antwerp Fine (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-472-08260-5.

- ^ John Van Antwerp Fine (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. pp. 349–350. ISBN 978-0-472-08260-5.

- ^ John Van Antwerp Fine (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. pp. 350–357, 544, 563. ISBN 978-0-472-08260-5.

- ^ Survey of International Affairs, By Arnold Joseph Toynbee, Veronica Marjorie Toynbee, Royal Institute of International Affairs. Published by Oxford University Press, 1958

- ^ Fleming, Katherine Elizabeth. The Muslim Bonaparte: Diplomacy and Orientalism in Ali Pasha's Greece. Princeton University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-691-00194-4, p. 59.

- ^ a b Barbara Jelavich. History of the Balkans: Eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Cambridge University Press, 1983. ISBN 0-521-27458-3, ISBN 978-0-521-27458-6

- ^ Kristin Fabbe. "Defining Minorities and Identities – Religious Categorization and State-Making Strategies in Greece and Turkey". Presentation at: The Graduate Student Pre-Conference in Turkish and Turkic Studies, University of Washington, October 18, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Ktistakis, Yiorgos. "Τσάμηδες – Τσαμουριά. Η ιστορία και τα εγκλήματα τους" [Chams – Chameria. Their History and Crimes] Cite error: The named reference "Ktistakis" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Dimitri Pentzopoulos, The Balkan Exchange of Minorities and Its Impact on Greece, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2002, ISBN 1-85065-674-6, ISBN 978-1-85065-674-6, p. 128

- ^ Onur Yildirim, Diplomacy and Displacement: Reconsidering the Turco-Greek Exchange of Populations, 1922–1934, CRC Press, 2006, ISBN 0-415-97982-X, ISBN 978-0-415-97982-5, p. 121

- ^ Drandakis Pavlos (editor), Great Greek Encyclopedia, vol. 23, article Tsamouria. Editions "Pyrsos", 1936–1934, in Greek language, p. 405

- ^ Great Greek Encyclopedia, vol. 10, p. 236. Anemi.lib.uoc.gr. Retrieved on 2014-02-01.

- ^ Roudometof, Victor (2002). Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-97648-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=Xoww453NVQMC

- ^ Meyer, Hermann Frank (2008) (in German). Blutiges Edelweiß: Die 1. Gebirgs-division im zweiten Weltkrieg [Bloodstained Edelweiss. The 1st Mountain-Division in WWII]. Ch. Links Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86153-447-1. pp. 152, 204, 464, 705.

- ^ Victor Roudometof, Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002. ISBN 978-0-275-97648-4, p. 182 "also the Cham collaboration with Germans is a fact, not an accusation.

- ^ Mazower, Mark. After The War Was Over: Reconstructing the Family, Nation and State in Greece, 1943–1960. Princeton University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-691-05842-3, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Baltsiotis. The Muslim Chams of Northwestern Greece. 2011. “In the official censuses of the Greek State in the Interwar period there is major manipulation involving the numbers of the Albanian speakers in the whole of the Greek territory.... The issue here is not the underestimation of the numbers of speakers as such, but the vanishing and reappearing of linguistic groups according to political motives, the crucial one being the “stabilization” of the total number of Albanian speakers in Greece.”

- ^ a b Baltsiotis. The Muslim Chams of Northwestern Greece. 2011. "The Orthodox Albanian-speakers’ “return” to Southern Greece and Epirus, Macedonia and Thrace also present at this time, at the 1951 census (7,357 are counted in Epirus)."

- ^ More recent historians have criticized these statistics and noted that they may have undercounted drastically the number of non-Grecophone Christians in the region. Lambros A. Psomas, for example, notes in his 2008 Ethnographic Synthesis of the Population of Southern Albania (Northern Epirus) In the Beginning of the 20th Century that according to the same statistics, not a single Vlach appears in Metsovo, which is known to be a major center of Vlach population

- ^ Cassavetes, Nicholas J. The question of North Epirus at the Peace conference. The Pan-Epirotic Union of America. Oxford University Press, American Branch: New York, 1919. Page 77. For Thesprotia, the figures for Margariti, Filiates and Paramythia are here combined. The paper can be accessed here: http://books.google.com/books?id=pFUMAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ Anamali, Skënder and Prifti, Kristaq. Historia e popullit shqiptar në katër vëllime. Botimet Toena, 2002, ISBN 99927-1-622-3.

- ^ Ktistakis, 1992: p. 8

- ^ Ktistakis, 1992: p. 9 (citing Krapsitis V., 1986: Οι Μουσουλμάνοι Τσάμηδες της Θεσπρωτίας (The Muslim Chams of Thesprotia), Athens, 1986, p. 181.

- ^ Baltsiotis. The Muslim Chams of Northwestern Greece. 2011

- ^ Baltsiotis. The Muslim Chams of Northwestern Greece. 2011

- ^ Baltsiotis. The Muslim Chams of Northwestern Greece. 2011. "A few hundred Muslims stayed behind. 127 of them were counted in the 1951 census, while the rest, whose number remains unknown and in need of research, converted to Christianity and intermarried with Greeks..... Except for two small communities that mostly avoided conversion, namely Kodra and Koutsi (actual Polyneri), the majority of others were baptized. Isolated family members that stayed behind were included in the Greek society, and joined the towns of the area or left for other parts of Greece (author’s field research in the area, 1996-2008)."

- ^ Sarah Green (2005). Notes from the Balkans: Locating Marginality and Ambiguity on the Greek-Albanian border. Princeton University Press. pp. 74-75. "Over time, and with some difficulty, I began to understand that the particular part of Thesprotia being referred to was the borderland area, and that the ‘terrible people’ were not all the peoples associated with Thesprotia but more specifically peoples known as the Tsamides –though they were rarely explicitly named as such in the Pogoni area. One of the few people who did explicitly refer to them was Spiros, the man from Despotiko on the southern Kasidiaris (next to the Thesprotia border) who had willingly fought with the communists during the civil war. He blamed widespread negative attitudes toward the Tsamides on two things: first, that in the past they were perceived to be ‘Turks’ in the same way as Albanian speaking Muslims had been perceived to be ‘Turks’; and second, there had been particularly intense propaganda against them during the two wars –propaganda that had led to large numbers of Tsamides’ being summarily killed by EDES forces under General Zervas. Zervas believed they had helped the Italian and later German forces when they invaded Greece, and thus ordered a campaign against them in retribution. Spiros went on to recall that two young men from Despotiko had rescued one endangered Tsamis boy after they came across him when they were in Thesprotia to buy oil. They brought him back to the village with them, and Spiros had baptized him in a barrel (many Tsamides were Muslim) in the local monastery. In the end, the boy had grown up, married in the village, and stayed there."

- ^ Georgia Kretsi (2002). "The Secret Past of the Greek-Albanian Borderlands. Cham Muslim Albanians: Perspectives on a Conflict over Historical Accountability and Current Rights". Ethnologia Balkanica.(6): 186. "In the census of 1951 there were only 127 Muslims left of a minority that once had 20,000 members. A few of them could merge into the Greek population by converting to Christianity and changing their names and marital practices. After the expulsion, two families of Lopësi found shelter in Sagiáda and some of their descendants still live there today under new names and being Christians. Another inhabitant of Lopësi, then a child, is living in nearby Asproklissi..... The eye-witness Arhimandritēs (n. d.: 93) writes about a gendarmerie officer and member of the EDES named Siaperas who married a very prosperous Muslim widow whose children had converted to Christianity. One interviewee, an Albanian Cham woman, told me that her uncle stayed in Greece, “he married a Christian, he changed his name, he took the name Spiro. Because it is like that, he changed it, and is still there in loannina, with his children“. A Greek man from Sagiáda also stated that at this time many people married and in saving the women also were able to take over their lands."

- ^ Euromosaic project (2006). "L'arvanite/albanais en Grèce" (in French). Brussels: European Commission. Retrieved 2015-05-07.

- ^ Vickers, Miranda and Petiffer, James. The Albanian Question. I.B. Tauris, 2007, ISBN 1-86064-974-2, p. 238.

- ^ Οδηγός Περιφέρειας Ηπείρου (10 December 2007). "Πρόσφυγες, Σαρακατσάνοι, Αρβανίτες". cultureportalweb. Retrieved 18-4-2015.

- ^ Georgoulas, Sokratis D.(1964). Λαογραφική Μελέτη Αμμουδιάς Πρεβέζης. Κέντρων Ερεύνης της Ελληνικής Λαογραφίας. pp. 2, 15.

- ^ Tsitsipis, Lukas (1981). Language change and language death in Albanian speech communities in Greece: A sociolinguistic study. (Thesis). University of Wisconsin. Ann Arbor. 124. "The Epirus Albanian speaking villages use a dialect of Tosk Albanian, and they are among the most isolated areas in Greece. In the Epiriotic village of Aghiá I was able to spot even a few monolingual Albanian speakers."

- ^ a b Foss, Arthur (1978). Epirus. Botston, United States of America: Faber. p. 224. ISBN 9780571104888. "There are still many Greek Orthodox villagers in Threspotia who speak Albanian among themselves. They are scattered north from Paramithia to the Kalamas River and beyond, and westward to the Margariti Plain. Some of the older people can only speak Albanian, nor is the language dying out. As more and more couples in early married life travel away to Athens or Germany for work, their children remain at home and are brought up by their Albania-speaking grandparents. It is still sometimes possible to distinguish between Greek- and Albanian-speaking peasant women. Nearly all of them wear traditional black clothes with a black scarf round their neck heads. Greek-speaking women tie their scarves at the back of their necks, while those who speak primarily Albanian wear their scarves in a distinctive style fastened at the side of the head."

- ^ Hart, Laurie Kain (1999). "Culture, Civilization, and Demarcation at the Northwest Borders of Greece". American Ethnologist. 26: 196. doi:10.1525/ae.1999.26.1.196.

Speaking Albanian, for example, is not a predictor with respect to other matters of identity .. There are also long standing Christian Albanian (or Arvanitika speaking) communities both in Epirus and the Florina district of Macedonia with unquestioned identification with the Greek nation. .. The Tschamides were both Christians and Muslims by the late 18th century [in the 20th century, Cham applies to Muslim only]

- ^ Moraitis, Thanassis. "publications as a researcher". thanassis moraitis: official website. Retrieved 18-4-2015. "Οι Αρβανίτες αυτοί είναι σε εδαφική συνέχεια με την Αλβανία, με την παρεμβολή του ελληνόφωνου Βούρκου (Vurg) εντός της Αλβανίας, και η Αλβανική που μιλιέται εκεί ακόμα, η Τσάμικη, είναι η νοτιότερη υποδιάλεκτος του κεντρικού κορμού της Αλβανικής, αλλά έμεινε ουσιαστικά εκτός του εθνικού χώρου όπου κωδικοποιήθηκε η Αλβανική ως επίσημη γλώσσα του κράτους..... Οι αλβανόφωνοι χριστιανοί θεωρούν τους εαυτούς τους Έλληνες. Στα Ελληνικά αποκαλούν τη γλώσσα τους «Αρβανίτικα», όπως εξ άλλου όλοι οι Αρβανίτες της Ελλάδας, στα Αρβανίτικα όμως την ονομάζουν «Σκιπ»"..... "The Albanian idiom still spoken there, Çamërisht, is the southernmost sub-dialect of the main body of the Albanian language, but has remained outside the national space where standard Albanian has been standardized as official language of the state..... Ethnic Albanophone Christians perceive themselves as national Greeks. When speaking Greek, members of this group call their idiom Arvanitic, just as all other Arvanites of Greece; yet, when conversing in their own idiom, they call it “Shqip”."

- ^ Tsitsipis. Language change and language death. 1981. p. 2. "The term Shqip is generally used to refer to the language spoken in Albania. Shqip also appears in the speech of the few monolinguals in certain regions of Greek Epirus, north-western Greece, while the majority of the bilingual population in the Epirotic enclaves use the term Arvanitika to refer to the language when talking in Greek, and Shqip when talking in Albanian (see Çabej 1976:61-69, and Hamp 1972: 1626-1627 for the etymological observations and further references)."

- ^ Baltsiotis. The Muslim Chams of Northwestern Greece. 2011 "The Albanian language, and the Christian population who spoke it- and still do- had to be concealed also, since the language was perceived as an additional threat to the Greekness of the land. It could only be used as a proof of their link with the Muslims, thus creating a continuum of non-Greekness."

- ^ Banfi, Emanuele (6 June 1994). Minorités linguistiques en Grèce: Langues cachées, idéologie nationale, religion (in French). Paris: Mercator Program Seminar. p. 27.

- ^ Adrian Ahmedaja (2004). "On the question of methods for studying ethnic minorities' music in the case of Greece's Arvanites and Alvanoi." in Ursula Hemetek (ed.). Manifold Identities: Studies on Music and Minorities. Cambridge Scholars Press. p. 59. "Among the Alvanoi the reluctance to declare themselves as Albanians and to speak to foreigners in Albanian was even stronger than among the Arvanites. I would like to mention just one example. After several attempts we managed to get the permission to record a wedding in Igoumenitsa. The participants were people from Mavrudi, a village near Igoumenitsa. They spoke to us only German or English, but to each other Albanian. There were many songs in Greek which I knew because they are sung on the other side of the border, in Albanian. I should say the same about a great part of the dance music. After a few hours, we heard a very well known bridal song in Albanian. When I asked some wedding guests what this kind of song was, they answered: You know, this is an old song in Albanian. There have been some Albanians in this area, but there aren’t any more, only some old people”. Actually it was a young man singing the song, as can he heard in audio example 5.9. The lyrics are about the bride’s dance during the wedding. The bride (swallow” in the song) has to dance slowly — slowly as it can be understood in the title of the song Dallëndushe vogël-o, dale, dale (Small swallow, slow — slow) (CD 12)."

- ^ Sarah Green (2005). Notes from the Balkans: Locating Marginality and Ambiguity on the Greek-Albanian border. Princeton University Press. pp. 74-75. "In short, there was a continual production of ambiguity in Epirus about these people, and an assertion that a final conclusion about the Tsamides was impossible. The few people I meet in Thesprotia who agreed that they were Tsamides were singularly reluctant to discuss anything to do with differences between themselves and anyone else. One older man said, ‘Who told you I’m a Tsamis? I’m no different from anyone else.’ That was as far as the conversation went. Another man, Having heard me speaking to some people in a Kafeneio in Thesprotia on the subject, followed me out of the shop as I left, to explain to me why people would not talk about Tsamides; he did not was to speak to me about it in the hearing of others: They had a bad reputation, you see. They were accused of being thieves and armatoloi. But you can see for yourself, there not much to live on around here. If some of them did act that way, it was because they had to, to survive. But there were good people too, you know; in any population, you get good people and bad people. My grandfather and my father after him were barrel makers, they were honest men. They made barrels for oil and tsipouro. I’m sorry that people have not been able to help you do your work. It’s just very difficult; it’s a difficult subject. This man went on to explain that his father was also involved in distilling tsipouro, and he proceeded to draw a still for me in my notebook, to explain the process of making this spirit. But he would not talk about any more about Tsamides and certainly never referred to himself as being Tsamis."

- ^ Winnifrith, Tom (1995). "Southern Albania, Northern Epirus: Survey of a Disputed Ethnological Boundary." Farsarotul. Retrieved 18-4-2015. "I tried unsuccessfully in 1994 to find Albanian speakers in Filiates, Paramithia and Margariti. The coastal villages near Igoumenitsa have been turned into tourist resorts. There may be Albanian speakers in villages inland, but as in the case with the Albanian speakers in Attica and Boeotia the language is dying fast. It receives no kind of encouragement. Albanian speakers in Greece would of course be almost entirely Orthodox."

- ^ Winnifrith, Tom (2002). Badlands, Borderlands: A History of Northern Epirus/Southern Albania. Duckworth. pp. 25-26, 53. “Some Orthodox speakers remained, but the language was not encouraged or even allowed, and by the end of the twentieth century it had virtually disappeared..... And so with spurious confidence Greek historians insist that the inscriptions prove that the Epirots of 360, given Greek names by their fathers and grandfathers at the turn of the century, prove the continuity of Greek speech in Southern Albania since their grandfathers whose names they might bear would have been living in the time of Thucydides. Try telling the same story to some present-day inhabitants of places like Margariti and Filiates in Southern Epirus. They have impeccable names, they speak only Greek, but their grandparents undoubtedly spoke Albanian.”

- ^ Raymond G. Gordon, Raymond G. Gordon, Jr., Barbara F. Grimes (2005) Summer Institute of Linguistics, Ethnologue: Languages of the World, SIL International, ISBN 1-55671-159-X.

- ^ Brian D. Joseph. When Languages Collide: Perspectives on Language Conflict, Language Competition, and Language Coexistence. Ohio State University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-8142-0913-4, p. 281

- ^ Jewish currents. 2000, p. 34.

- ^ Miranda Vickers, The Albanians: A Modern History, I.B.Tauris, 1999, ISBN 1-86064-541-0, ISBN 978-1-86064-541-9

- ^ Σε αρβανιτοχώρι της Θεσπρωτίας αναβίωσαν τον αρβανίτικο γάμο! [In an Arvanite village, Arvanite customs have reappeared !]". Katopsi. Retrieved 18-4-2015.

See also

Further reading

- Baltsiotis, Lambros (2011). "The Muslim Chams of Northwestern Greece: The grounds for the expulsion of a "non-existent" minority community". European Journal of Turkish Studies. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Elsie, Robert & Bejtullah Destani (2013). The Cham Albanians of Greece. A Documentary History. IB Tauris. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- Albania at War, 1939–45, Bernd I. Fischer, p. 85. C. Hurst & Co, 1999

- Historical Atlas of Central Europe, 2nd. ed. Paul Robert Magocsi. Seattle: U. of Washington Press, 2002.

- Roudometof, Victor. Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question.

- Clogg, Richard. A Concise History of Greece. Cambridge University Press, 2002.