Frederick Lugard, 1st Baron Lugard: Difference between revisions

m →Exploration of East Africa: spelling correction |

Rescuing 2 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.5.4) |

||

| Line 110: | Line 110: | ||

==League of Nations and Anti-Slavery activism== |

==League of Nations and Anti-Slavery activism== |

||

Between 1922 and 1936, Lugard was the British representative on the [[League of Nations]]' [[Permanent Mandates Commission]]. During this period he served first on the [[Temporary Slavery Commission]] and was involved in organising the [[1926 Slavery Convention]]. He had submitted a proposal for the Convention to the British government. Although they were initially alarmed by it, the British government backed the proposal (after subjecting it to considerable redrafting) and it was eventually enacted.<ref name=Miers>{{cite web|last=Miers|first=Suzanne|title="Freedom is a good thing but it means a dearth of slaves": Twentieth Century Solutions to the Abolition of Slavery|url=https://www.yale.edu/glc/events/cbss/Miers.pdf|publisher=Yale University|accessdate=7 December 2013}}</ref> Lugard served on the [[International Labour Organization]]'s Committee of Experts on Native Labour from 1925 to 1941.<ref>{{Citation |publisher = ABC-CLIO |publication-place = Santa Barbara, California |title = The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery |url = http://openlibrary.org/books/OL25434623M/The_Historical_Encyclopedia_of_World_Slavery |author = Junius P. Rodriguez |publication-date = 1997 |oclc = 37884790}}</ref> |

Between 1922 and 1936, Lugard was the British representative on the [[League of Nations]]' [[Permanent Mandates Commission]]. During this period he served first on the [[Temporary Slavery Commission]] and was involved in organising the [[1926 Slavery Convention]]. He had submitted a proposal for the Convention to the British government. Although they were initially alarmed by it, the British government backed the proposal (after subjecting it to considerable redrafting) and it was eventually enacted.<ref name=Miers>{{cite web|last=Miers|first=Suzanne|title="Freedom is a good thing but it means a dearth of slaves": Twentieth Century Solutions to the Abolition of Slavery|url=https://www.yale.edu/glc/events/cbss/Miers.pdf|publisher=Yale University|accessdate=7 December 2013|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20131207162421/http://www.yale.edu/glc/events/cbss/Miers.pdf|archivedate=7 December 2013|df=dmy-all}}</ref> Lugard served on the [[International Labour Organization]]'s Committee of Experts on Native Labour from 1925 to 1941.<ref>{{Citation |publisher = ABC-CLIO |publication-place = Santa Barbara, California |title = The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery |url = http://openlibrary.org/books/OL25434623M/The_Historical_Encyclopedia_of_World_Slavery |author = Junius P. Rodriguez |publication-date = 1997 |oclc = 37884790}}</ref> |

||

==Views== |

==Views== |

||

| Line 162: | Line 162: | ||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

{{commons category|Frederick Lugard, 1st Baron Lugard}} |

{{commons category|Frederick Lugard, 1st Baron Lugard}} |

||

*[http://www.archiveshub.ac.uk/news/0300fdl.html Archives Hub:Papers of Frederick Dealtry Lugard, Baron Lugard of Abinger: 1871-1969] |

*[https://archive.is/20121222234436/http://www.archiveshub.ac.uk/news/0300fdl.html Archives Hub:Papers of Frederick Dealtry Lugard, Baron Lugard of Abinger: 1871-1969] |

||

{{S-start}} |

{{S-start}} |

||

Revision as of 09:23, 7 October 2017

The Lord Lugard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Governor-General of Nigeria | |

| In office 1 January 1914 – 8 August 1919 | |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Sir Hugh Clifford (as Governor) |

| Governor of the Northern Nigeria Protectorate | |

| In office September 1912 – 1 January 1914 | |

| Preceded by | Sir Charles Lindsay |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Governor of the Southern Nigeria Protectorate | |

| In office September 1912 – 1 January 1914 | |

| Preceded by | Sir Walter Egerton |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| 14th Governor of Hong Kong | |

| In office 29 July 1907 – 16 March 1912 | |

| Preceded by | Sir Matthew Nathan |

| Succeeded by | Sir Francis Henry May |

| High Commissioner of the Northern Nigeria Protectorate | |

| In office 6 January 1900 – September 1906 | |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Sir William Wallace (acting) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 22 January 1858 Madras, British India |

| Died | 11 April 1945 (aged 87) Dorking, Surrey, England, UK |

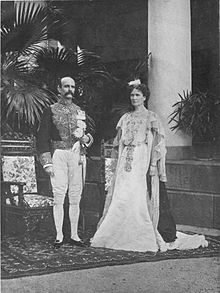

| Spouse | Flora Shaw |

| Alma mater | Royal Military College, Sandhurst |

| Profession | Soldier, explorer, colonial administrator |

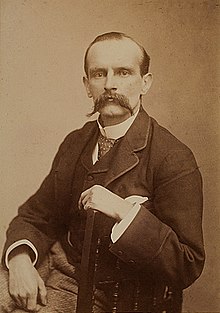

Frederick John Dealtry Lugard, 1st Baron Lugard GCMG, CB, DSO, PC (22 January 1858 – 11 April 1945), known as Sir Frederick Lugard between 1901 and 1928, was a British soldier, mercenary, explorer of Africa and colonial administrator. He was Governor of Hong Kong (1907–1912), the last Governor of the Southern Nigeria Protectorate (1912–1914), the first High Commissioner (1900–1906) and last Governor (1912–1914) of the Northern Nigeria Protectorate and the first Governor-General of Nigeria (1914–1919).

Early life and education

Lugard was born in Madras (now Chennai) in India, but was raised in Worcester, England. He was the son of the Rev'd Frederick Grueber Lugard, a British Army chaplain at Madras, and his third wife Mary Howard (1819–1865), the youngest daughter of Rev'd John Garton Howard (1786–1862), a younger son of landed gentry from Thorne and Melbourne near York. Lugard was educated at Rossall School and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst.

The name 'Dealtry' was in honour of Thomas Dealtry, a friend of his father.

Military career

Lugard was commissioned into the 9th Foot (East Norfolk Regiment) in 1878, joining the second battalion in India and serving in the following campaigns:

- 2nd Afghan War (1879–1880)

- Sudan campaign (1884–1885)

- Third Burmese War (1886–1887)

Lugard was appointed to the Distinguished Service Order in 1887.[1] In May 1888, he took command of an expedition organised by the British settlers in Nyasaland against Arab slave traders on Lake Nyasa and was severely wounded.

Exploration of East Africa

After leaving Nyasaland in April 1889, Lugard accepted a position with the Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC) and arrived in Mombasa on the coast of east Africa that December[2]. A year earlier in 1888, the IBEAC had been granted a royal charter by Queen Victoria to exploit the 'British sphere of influence' between Zanzibar and Uganda[3] and were keen to open a trading route between Lake Victoria in Uganda and the coastal port of Mombasa. Their first interior trading post was established at Machakos 240 miles in from the coast. But the established traditional route to Machakos was a treacherous journey through the large Taru Desert--93 miles of scorching dust bowl.

Lugard's first mission was to determine the feasibility of a route from Mombasa to Machakos that would bypass the Taru Desert.[4] He explored the Sabaki river and the neighbouring region, in addition to elaborating a scheme for the emancipation of the slaves held by Arabs in the Zanzibar mainland.

In August 1890, Lugard departed on foot from Mombasa for Uganda to secured British predominance over German influence in the area and put an end to the civil disturbances between factions in the kingdom of Buganda[5][6].

En route, Lugard was instructed to enter into treaties with local tribes and build forts in order to secure safe passage for future IBEAC expeditions[7]. The IBEAC employed official treaty documents that were signed by their administrator and the local leaders but Lugard preferred the more equitable blood brotherhood ceremony[2] and entered into several brotherhood partnerships with leaders who inhabited the areas between Mombasa and Uganda. One of his famed blood partnerships was sealed in October 1890 during his journey to Uganda when he stopped at Dagoretti in Kikuyu territory and entered into an alliance with Waiyaki wa Hinga[8].

Lugard was Military Administrator of Uganda from 26 December 1890 to May 1892. While administering Uganda, he journeyed round the Rwenzori Mountains to Lake Edward, mapping a large area of the country. He also visited Lake Albert and brought away some thousands of Sudanese who had been left there by Emin Pasha and H. M. Stanley during the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition.

When Lugard returned to England in 1892, he successfully dissuaded Prime Minister William Gladstone from abandoning Uganda.

Early colonial service

In 1894, Lugard was dispatched by the Royal Niger Company to Borgu, where he secured treaties with the kings and chiefs who acknowledged the sovereignty of the British company, while reducing the influence of other colonial powers. From 1896 to 1897, Lugard took charge of an expedition to Lake Ngami, in modern-day Botswana, on behalf of the British West Charterland Company. He was recalled from Ngami by the British government and sent to West Africa, where he was commissioned to raise a native force to protect British interests in the hinterland of the Lagos Colony and Nigeria against French aggression. In August 1897, Lugard organised the West African Frontier Force and commanded it until the end of December 1899, when the disputes with France were settled.

After relinquishing command of the West African Frontier Force, Lugard was appointed High Commissioner of the newly created Protectorate of Northern Nigeria. He was present at Lokoja and read the proclamation that established the protectorate on 1 January 1900.[9] At that time, the portion of Northern Nigeria under effective control was small, and Lugard's task in organising this vast territory was made more difficult by the refusal of the sultan of Sokoto and many other Fula princes to fulfil their treaty obligations.

In 1903, British control over the whole protectorate was made possible by a successful campaign against the emir of Kano and the sultan of Sokoto. By the time Lugard resigned as commissioner in 1906, the entire Nigeria was being peacefully administered under the supervision of British residents.[citation needed] There were, though, uprisings that were brutally put down by Lugard's troops. A Mahdi rebellion in 1906 at the Satiru, a village near Sokoto, resulted in the total destruction of the town and huge numbers of casualties.[citation needed]

Lugard was knighted in 1901 for his service in Nigeria.[10]

Governor of Hong Kong

About a year after he resigned as High Commissioner of the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria, Lugard was appointed Governor of Hong Kong,[11] a position he held until March 1912. During his tenure, Lugard proposed to return Weihaiwei to the Chinese government, in return for the ceding of the rented New Territories in perpetuity. However, the proposal was neither well received nor acted upon. Some believed that if the proposal were carried through, Hong Kong might forever remain in British hands.

Lugard's chief interest was education and he was largely remembered for his efforts to the founding of the University of Hong Kong in 1911. He became the first chancellor, despite a cold receptions from the imperial Colonial Office and local British companies, such as the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation. The Colonial Office called the idea of a university "Sir Frederick's pet lamb".[12] In fact, Lugard's idea was to create a citadel of higher education which could serve as the foremost bearer of Western culture in the Orient.

Governor of Nigeria

In 1912, Lugard returned to Nigeria as Governor of the two protectorates. His mission was to amalgamate the two colonies into one. Although controversial in Lagos, where it was opposed by a large section of the political class and the media, the amalgamation did not arouse passion in the rest of the country because the people were unaware of the implications.[citation needed] Lugard took scant notice of public opinion, neither did he feel there was need for consensus among the locals on such a serious political subject which had such key implications for the two colonies.[citation needed] From 1914 to 1919, Lugard served as Governor General of the now combined colony of Nigeria. Throughout his tenure, he sought strenuously to secure the amelioration of the condition of the native people, among other means by the exclusion, wherever possible, of alcoholic liquors, and by the suppression of slave raiding and slavery.[citation needed]

Lugard, assisted by his indefatigable wife, Flora Shaw, concocted a legend which warped understanding of him, Nigeria and colonialism for decades. He believed that "the typical African ... is a happy, thriftless, excitable person, lacking in self control, discipline and foresight, naturally courageous, courteous and polite, full of personal vanity, with little of veracity; in brief, the virtues and defects of this race-type are those of attractive children."[13]

Funding of the colony of Nigeria in the development of state's infrastructure such as harbours, railways and hospitals in Southern Nigeria came from revenue generated by taxes on imported alcohol. In Northern Nigeria, the revenue that allowed state development projects was less because the taxes was absent and thus funding of projects was covered from revenue generated in the south. [citation needed]

The Adubi War occurred during his governorship. In Northern Nigeria, Lugard permitted slavery within traditional elite families. He loathed the educated and sophisticated Africans of the coastal regions. Lugard ran the country whilst spending half each year in England, where he could promote himself and was distant from realities in Africa, where subordinates had to delay decisions on many matters until he returned. He based his rule on a military system - unlike William MacGregor, a doctor turned governor, who mixed with all ranks of people and listened to what was wanted.[14] The Lugard who opposed "native education" later became involved in Hong Kong University, and the man who disliked traders and businessmen became a director of a Nigerian bank.

The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa

Lugard's The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa was published in 1922 and discussed indirect rule in colonial Africa. In this work, Lugard outlined the reasons and methods that he recommended for the colonisation of Africa by Britain. Some of his justifications included spreading Christianity and ending 'barbarism' (such as human sacrifice). He also saw state-sponsored colonisation as a way to protect missionaries, local chiefs and local people from each other, as well as from foreign powers. For Lugard, it was also vital that Britain gain control of unclaimed areas before Germany, Portugal or France claimed the land and its resources for themselves. He realised that there were vast profits to be made through the export of resources such as rubber, and through taxation of native populations as well as importers and exporters (The British taxpayer continually made a loss from the colonies in this period). In addition, these resources and inexpensive native labour (slavery having been outlawed by Britain in 1834) would provide vital fuel for the industrial revolution in resource-depleted Britain, as well as monies for public works projects. Finally, Lugard reasoned that colonisation had become a fad and that, in order to remain a super power, Britain would need to hold colonies to avoid appearing weak.

League of Nations and Anti-Slavery activism

Between 1922 and 1936, Lugard was the British representative on the League of Nations' Permanent Mandates Commission. During this period he served first on the Temporary Slavery Commission and was involved in organising the 1926 Slavery Convention. He had submitted a proposal for the Convention to the British government. Although they were initially alarmed by it, the British government backed the proposal (after subjecting it to considerable redrafting) and it was eventually enacted.[15] Lugard served on the International Labour Organization's Committee of Experts on Native Labour from 1925 to 1941.[16]

Views

Lugard pushed for native rule in African colonies. He reasoned that black Africans were very different from white Europeans, although he did speculate on the admixture of Aryan or Hamitic blood arising from the advent of Islam among the Hausa and Fulani.[17] He considered that natives should act as a sort of middle manager in colonial governance. This would avoid revolt because, he believed, the people of Africa would be more likely to follow someone who looked like them, spoke their languages and shared their customs.

Olufemi Taiwo argues that Lugard actually blocked qualified Africans, who had been educated in Britain, from playing an active role in the development of the country; he distrusted white "intellectuals" as much as black ones - believing that the principles they were taught in the universities were often wrong. He preferred to advance prominent Hausa and Fulani leaders from traditional structures.[18]

Honours

Lugard was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB) in 1895.[19] He was knighted as a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (KCMG) in the 1901 New Year Honours[10] and raised to a Knight Grand Cross (GCMG) in 1911. He was appointed to the Privy Council in the 1920 New Year Honours.[20] In 1928 he was further honoured when he was elevated to the peerage as Baron Lugard, of Abinger in the County of Surrey.[21]

The Royal Geographical Society awarded him the Founder′s Gold Medal in 1902 for persistent attention to African geography.[22]

A bronze bust of Lugard, created by Pilkington Jackson in 1960, is held in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Personal life

Lugard married, on 10 June 1902, Flora Shaw,[23] daughter of Major-General George Shaw, and granddaughter of Sir Frederick Shaw, 3rd Baronet. She was a writer for The Times and coined the place-name Nigeria. There were no children from the marriage. She died in January 1929; Lugard survived her by sixteen years and died on 11 April 1945, aged 87. Since he was childless, the barony became extinct. He was cremated at Woking Crematorium.

Published works

- In 1893, Lugard published The Rise of our East African Empire, which was partially an autobiography. He was also the author of various valuable reports on Northern Nigeria issued by the Colonial Office.

- The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa, 1922.

See also

References

- ^ "No. 25761". The London Gazette. 25 November 1887. p. 6374.

- ^ a b Charles., Miller, (2015). The Lunatic Express. Head of Zeus. p. 4015. ISBN 9781784972714. OCLC 968732897.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Imperial British East Africa Company - IBEAC". Softkenya.com. 10 January 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ Miller, Charles (2015). The Lunatic Express. London: Head of Zeus Ltd. 4022. ISBN 9781784972714.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ The London Quarterly and Holborn Review. E.C. Barton. 1894. p. 330.

- ^ Youé, Christopher P. (1 January 2006). Robert Thorne Coryndon: Proconsular Imperialism in Southern and Eastern Africa, 1897-1925. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. p. 126. ISBN 9780889205482.

- ^ Nicholls, Christine Stephanie (2005). Red Strangers: The White Tribe of Kenya. Timewell Press. p. 10. ISBN 9781857252064.

- ^ Osborne, Myles; Kent, Susan Kingsley (24 March 2015). Africans and Britons in the Age of Empires, 1660-1980. Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 9781317514817.

- ^ "The Transfer of Nigeria to the Crown". The Times. No. 36060. London. 8 February 1900. p. 7. template uses deprecated parameter(s) (help)

- ^ a b "No. 27261". The London Gazette. 1 January 1901. p. 1.

- ^ "No. 28024". The London Gazette. 24 May 1907. p. 3589.

- ^ Carroll JM (2007). A Concise History of Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press. p.85.

- ^ Gann, Lewis H; Duignan, Peter (1978). The Rulers of British Africa 1870—1914 (1st ed.). Stanford CA: Stanford University Press. p. 340. ISBN 0-8047-0981-5.

- ^ Nicholson, I F (1969). The Administration of Nigeria 1900 to 1960. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0981-5.

- ^ Miers, Suzanne. ""Freedom is a good thing but it means a dearth of slaves": Twentieth Century Solutions to the Abolition of Slavery" (PDF). Yale University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Junius P. Rodriguez (1997), The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery, Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, OCLC 37884790

- ^ The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa p76

- ^ 'Reading the Colonizer's Mind: Lord Lugard and the Philosophical Foundations of British Colonialism' by Olufemi Taiwo in Racism and Philosophy edited by Susan E. Babbitt and Sue Campbell, Cornell University Press, 1999

- ^ "No. 26639". The London Gazette. 2 July 1895. p. 3740.

- ^ "No. 31712". The London Gazette (Supplement). 30 December 1919. p. 1.

- ^ "No. 33369". The London Gazette. 23 March 1928. p. 2129.

- ^ "Royal Geographical Society". The Times. No. 36716. London. 15 March 1902. p. 12. template uses deprecated parameter(s) (help)

- ^ "Court Circular". The Times. No. 36792. London. 12 June 1902. p. 12. template uses deprecated parameter(s) (help)

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Lugard, Sir Frederick John Dealtry". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Biography, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Further reading

- Lord Lugard, Frederick D. (1965). The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa. Fifth Edition. London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

- Pederson, Susan (2015). The Guardians: the League of Nations and the Crisis of Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Perham, Margery (1956). Lugard. Volume 1: The Years of Adventure 1858-1898. London: Collins.

- Perham, Margery (1960). Lugard. Volume 2: The Years of Authority 1898-1945. London: Collins.

- Perham, Margery (ed.) (1959). The Diaries of Lord Lugard (3 Vols.). London: Faber & Faber.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Middleton, Dorothy (1959). Lugard in Africa. London: Robert Hale, Ltd.

- Miller, Charles (1971). The Lunatic Express, An Entertainment in Imperialism.

- Meyer and Brysac (2008). Kingmakers: the Invention of the Modern Middle East. New York, London: W.W. Norton.

- Taiwo, Alufemi (1999). "Reading the Colonizer's Mind: Lord Lugard and the Philosophical Foundations of British Colonialism". In Babbitt, Susan E; Campbell, Sue (eds.). Racism and Philosophy. Cornell University Press.

External links

- 1858 births

- 1945 deaths

- Military personnel from Chennai

- People from Worcester

- People educated at Rossall School

- Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst

- Royal Norfolk Regiment officers

- Royal West African Frontier Force officers

- British military personnel of the Second Anglo-Afghan War

- British Army personnel of the Mahdist War

- British military personnel of the Third Anglo-Burmese War

- Barons in the Peerage of the United Kingdom

- English explorers

- Companions of the Distinguished Service Order

- Explorers of Africa

- Governors of Hong Kong

- British Governors and Governors-General of Nigeria

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George

- Companions of the Order of the Bath

- Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

- Vice-Chancellors of the University of Hong Kong

- Nigeria in World War I

- British expatriates in Hong Kong

- History of Lagos

- 20th-century Hong Kong people

- 20th-century British politicians