Bantu peoples: Difference between revisions

Paleogenetics do actually support the eastward ancient Bantu migration (https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(17)31008-5) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

[[File:Bantu zones.png|thumb|right|Bantu languages divided into zones according to the [[Guthrie classification of Bantu languages]]]] |

[[File:Bantu zones.png|thumb|right|Bantu languages divided into zones according to the [[Guthrie classification of Bantu languages]]]] |

||

'''Bantu peoples''' is used as a general label for the 300–600 [[List of ethnic groups of Africa|ethnic groups in Africa]] who speak [[Bantu languages]].<ref name="Tgdwh">{{cite book|last=Butt|first=John J.|title=The Greenwood Dictionary of World History|year=2006|publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group|isbn=0-313-32765-3|page=39}}</ref> They inhabit a geographical area stretching east and southward from [[Central Africa]] across the [[African Great Lakes]] region down to [[Southern Africa]].<ref name="Tgdwh" /> Bantu is a major branch of the [[Niger–Congo]] [[language family]] spoken by most populations in Africa. There are about 650 Bantu languages by the criterion of [[mutual intelligibility]],<ref>Derek Nurse, 2006, "Bantu Languages", in the ''Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics''</ref> though the [[Dialect#Dialect_or_language|distinction between language and dialect]] is often unclear, and ''[[Ethnologue]]'' counts 535 languages.<ref>[http://www.ethnologue.com/show_family.asp?subid=73-16 Ethnologue report for Southern Bantoid]. The figure of 535 includes the 13 [[Mbam languages]] considered Bantu in Guthrie's classification and thus counted by Nurse (2006)</ref> |

'''Bantu peoples''' is used as a general label for the 300–600 [[List of ethnic groups of Africa|ethnic groups in Africa]] who speak [[Bantu languages]].<ref name="Tgdwh">{{cite book|last=Butt|first=John J.|title=The Greenwood Dictionary of World History|year=2006|publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group|isbn=0-313-32765-3|page=39}}</ref> They inhabit a geographical area stretching east and southward from [[Central Africa]] across the [[African Great Lakes]] region down to [[Southern Africa]].<ref name="Tgdwh" /> Bantu is a major branch of the [[Niger–Congo]] [[language family]] spoken by most populations in Africa. There are about 650 Bantu languages by the criterion of [[mutual intelligibility]],<ref>Derek Nurse, 2006, "Bantu Languages", in the ''Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics''</ref> though the [[Dialect#Dialect_or_language|distinction between language and dialect]] is often unclear, and ''[[Ethnologue]]'' counts 535 languages.<ref>[http://www.ethnologue.com/show_family.asp?subid=73-16 Ethnologue report for Southern Bantoid]. The figure of 535 includes the 13 [[Mbam languages]] considered Bantu in Guthrie's classification and thus counted by Nurse (2006)</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Archaeological, linguistic and genetic data suggest that,<ref name="Skoglund"/> around 3,000 years ago, speakers of the [[Proto-Bantu language|Proto-Bantu]] language group began a millennia-long series of migrations eastward from their imagined homeland between [[West Africa]] and Central Africa, at the border of eastern [[Nigeria]] and [[Cameroon]].<ref>Philip J. Adler, Randall L. Pouwels, ''World Civilizations: To 1700 Volume 1 of World Civilizations'', (Cengage Learning: 2007), p.169.</ref> This theory was at first derived from linguistic evidence advanced by [[Joseph Greenberg]] in 1972<ref>Greenberg, J. (1972). Linguistic Evidence Regarding Bantu Origins. The Journal of African History, 13(2), 189-216. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/180851</ref><ref>Oliver, R. (1966). The Problem of the Bantu Expansion. The Journal of African History, 7(3), 361-376. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/180108</ref> Greenberg's theory was in competition with one advanced by professor of Bantu languages, [[Malcolm Guthrie]], who placed Bantu origins at the upper region of the Great Lakes region north of [[White Nile|Albert Nile]]<ref>https://books.google.co.ke/books/about/Comparative_Bantu.html?id=WZZkAAAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y,pg 1-180</ref> Guthrie theory's lost favor and Greenberg's theory gained prominence as the solution to the 'Bantu Problem', which later came to be known as the [[Bantu expansion]]. This ancient series of migrations were thought to have first introduced Bantu peoples to central, southern and southeastern Africa, regions they had previously been absent from before 800 B.C<ref>https://www.medievalworlds.net/0xc1aa5576_0x00348d17.pdf,pg 10</ref><ref>http://www.msu.ac.zw/elearning/material/temp/1329553910Vansina%201995%20linguistic%20evidence%20and%20bantu%20migrations.pdf,pg 9,11,17,18,19</ref> The proto-Bantu migrants in the process assimilated and/or displaced a number of earlier inhabitants that they came across, such as [[Pygmy peoples|Pygmy]] and [[Khoisan]] populations in the centre and south, respectively. They also encountered some [[Afroasiatic languages|Afro-Asiatic]] outlier groups in the southeast who had been there for centuries, having migrated from [[Northeast Africa]].<ref name="Falola">Toyin Falola, Aribidesi Adisa Usman, ''Movements, borders, and identities in Africa'', (University Rochester Press: 2009), pp.4-5.</ref><ref name="Fitzpatrick">{{cite book|last=Fitzpatrick|first=Mary|title=Tanzania, Zanzibar & Pemba|year=1999|publisher=Lonely Planet|isbn=0-86442-726-3|page=39}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Archaeological, linguistic and genetic data suggest that,<ref name="Skoglund"/> around 3,000 years ago, speakers of the [[Proto-Bantu language|Proto-Bantu]] language group began a millennia-long series of migrations eastward from their imagined homeland between [[West Africa]] and Central Africa, at the border of eastern [[Nigeria]] and [[Cameroon]].<ref>Philip J. Adler, Randall L. Pouwels, ''World Civilizations: To 1700 Volume 1 of World Civilizations'', (Cengage Learning: 2007), p.169.</ref> This theory was at first derived from linguistic evidence advanced by [[Joseph Greenberg]] in 1972<ref>Greenberg, J. (1972). Linguistic Evidence Regarding Bantu Origins. The Journal of African History, 13(2), 189-216. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/180851</ref><ref>Oliver, R. (1966). The Problem of the Bantu Expansion. The Journal of African History, 7(3), 361-376. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/180108</ref> Greenberg's theory was in competition with one advanced by professor of Bantu languages, [[Malcolm Guthrie]], who placed Bantu origins at the upper region of the Great Lakes region north of [[White Nile|Albert Nile]]<ref>https://books.google.co.ke/books/about/Comparative_Bantu.html?id=WZZkAAAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y,pg 1-180</ref> Guthrie theory's lost favor and Greenberg's theory gained prominence as the solution to the 'Bantu Problem', which later came to be known as the [[Bantu |

||

Individual Bantu groups today often comprise millions of people. Among these are the [[Northern Ndebele people|Ndebele]] and [[Shona people|Shona]] of [[Zimbabwe]] with 14.2 million people; the [[Luba people|Luba]] of the [[Democratic Republic of the Congo]], with over 13.5 million people; the [[Zulu people|Zulu]] of [[South Africa]], with over 10 million people; the [[Sukuma people|Sukuma]] of [[Tanzania]], with around eight million people; and the [[Kikuyu people|Kikuyu]] of Kenya, with over six million people. Although only around five million individuals speak the [[Arabic]]-influenced [[Swahili language]] as their [[mother tongue]],<ref>{{cite book |title=African folklore: an encyclopedia |last=Peek |first=Philip M. |authorlink= |author2=Kwesi Yankah |year=2004 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=0-415-93933-X |page=699}}</ref> it is used as a ''[[lingua franca]]'' by over 100 million people throughout Southeast Africa.<ref>Irele 2010</ref> Swahili also serves as one of the official [[languages of the African Union]]. |

Individual Bantu groups today often comprise millions of people. Among these are the [[Northern Ndebele people|Ndebele]] and [[Shona people|Shona]] of [[Zimbabwe]] with 14.2 million people; the [[Luba people|Luba]] of the [[Democratic Republic of the Congo]], with over 13.5 million people; the [[Zulu people|Zulu]] of [[South Africa]], with over 10 million people; the [[Sukuma people|Sukuma]] of [[Tanzania]], with around eight million people; and the [[Kikuyu people|Kikuyu]] of Kenya, with over six million people. Although only around five million individuals speak the [[Arabic]]-influenced [[Swahili language]] as their [[mother tongue]],<ref>{{cite book |title=African folklore: an encyclopedia |last=Peek |first=Philip M. |authorlink= |author2=Kwesi Yankah |year=2004 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=0-415-93933-X |page=699}}</ref> it is used as a ''[[lingua franca]]'' by over 100 million people throughout Southeast Africa.<ref>Irele 2010</ref> Swahili also serves as one of the official [[languages of the African Union]]. |

||

Revision as of 17:59, 29 April 2018

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Central Africa Southern Africa, African Great Lakes | |

| Languages | |

| Bantu languages (over 535), English, French, Portuguese, Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| predominantly: Christianity, traditional faiths; minority: Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Niger–Congo-speaking groups |

Bantu peoples is used as a general label for the 300–600 ethnic groups in Africa who speak Bantu languages.[1] They inhabit a geographical area stretching east and southward from Central Africa across the African Great Lakes region down to Southern Africa.[1] Bantu is a major branch of the Niger–Congo language family spoken by most populations in Africa. There are about 650 Bantu languages by the criterion of mutual intelligibility,[2] though the distinction between language and dialect is often unclear, and Ethnologue counts 535 languages.[3] Archaeological, linguistic and genetic data suggest that,[4] around 3,000 years ago, speakers of the Proto-Bantu language group began a millennia-long series of migrations eastward from their imagined homeland between West Africa and Central Africa, at the border of eastern Nigeria and Cameroon.[5] This theory was at first derived from linguistic evidence advanced by Joseph Greenberg in 1972[6][7] Greenberg's theory was in competition with one advanced by professor of Bantu languages, Malcolm Guthrie, who placed Bantu origins at the upper region of the Great Lakes region north of Albert Nile[8] Guthrie theory's lost favor and Greenberg's theory gained prominence as the solution to the 'Bantu Problem', which later came to be known as the Bantu expansion. This ancient series of migrations were thought to have first introduced Bantu peoples to central, southern and southeastern Africa, regions they had previously been absent from before 800 B.C[9][10] The proto-Bantu migrants in the process assimilated and/or displaced a number of earlier inhabitants that they came across, such as Pygmy and Khoisan populations in the centre and south, respectively. They also encountered some Afro-Asiatic outlier groups in the southeast who had been there for centuries, having migrated from Northeast Africa.[11][12]

Individual Bantu groups today often comprise millions of people. Among these are the Ndebele and Shona of Zimbabwe with 14.2 million people; the Luba of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with over 13.5 million people; the Zulu of South Africa, with over 10 million people; the Sukuma of Tanzania, with around eight million people; and the Kikuyu of Kenya, with over six million people. Although only around five million individuals speak the Arabic-influenced Swahili language as their mother tongue,[13] it is used as a lingua franca by over 100 million people throughout Southeast Africa.[14] Swahili also serves as one of the official languages of the African Union.

Etymology

The word Bantu, and its variations, means "people" or "humans". The root in Proto-Bantu is reconstructed as *-ntu. Versions of the word Bantu (that is, the root plus the class 2 noun class prefix *ba-) occur in all Bantu languages: for example, as watu in Swahili; bantu in Kikongo; anthu in Chichewa; batu in Lingala; bato in Kiluba; bato in Duala; abanto in Gusii; andũ in Kamba and Kikuyu; abantu in Kirundi, Kinyarwanda, Zulu, Xhosa, Runyakitara,[15] and Ganda; wandru in Shingazidja; abantru in Mpondo and Ndebele; bãtfu in Phuthi; bantfu in Swati; banu in Lala; vanhu in Shona and Tsonga; batho in Sesotho, Tswana and Northern Sotho; antu in Meru; andu in Embu; vandu in some Luhya dialects; vhathu in Venda; and bhandu in Nyakyusa[16][17].

History

Origins

Bantu-speaking peoples today inhabit most of equatorial Africa, in an area encompassing parts of West Africa, most of Central Africa, and parts of Southeast Africa and Southern Africa.[18] The question of the origin of these closely related languages was first posed around 1505 AD, when Portuguese explorers, solders and missionaries started learning Shona and Kiswahili.[19] Beginning in 1652 AD, the Dutch settlers in South Africa beginning also noted a close relationship between the languages spoken in the area all the way to eastern Swahili coast.[20] The French traders,in West Africa coasts of Guinea and Cameroon around 1730 AD also noted the similarity between the languages spoken in southern African with those spoken in Guinea and Cameroon.[21][22][23]

These early European visitors to Africa just noted the casual similarity in the languages. However in 1860,Wilhelm Bleek did a systematic study of the South African languages using the new comparative method[24].Bleek also coined and popularized the term 'Bantu' to describe these very closely related languages.Sir Henry Hamilton Johnston,in 1889 was the first European to inquire where Bantu speaking people came from when he explored the question of how Africa came to be populated by its present inhabitants[25].Sir Henry Hamilton Johnston also did further studies on Bantu languages and their origins,placing the Bantu original homeland in the area between L.Victoria,Eastern DRC and Southern fridges of Sudan[26][27]. Carl Meinhof in 1915 advanced this Bantu languages study further by investigating the origin of these Bantu languages and their relationship to other languages of Africa[28]. Professor Malcolm Guthrie took up the Bantu languages study and attempted to use linguistic methods to determine the origin of Bantu people and their languages.Guthrie in 1967 placed the Bantu origin in the area between L.Victoria,Eastern DRC and southern fridges of Sudan[29].A competing theory was advanced by Joseph Greenberg.Greenberg theory used tentative linguistic evidence to suggest that Bantu people and their languages originated in West Africa in the southern grasslands of Cameroon and Nigeria border[30] Jan Vansina argued that archaeological, linguistic and genetic studies did not support Greenberg's theory, and therefore referred to the spread of the Bantu languages as the 'Bantu Problem'.[31][32][33] However, paleogenetic analysis of ancient fossils in eastern Africa has found that present-day Bantu speakers in the region primarily trace their ancestry to a lineage related to modern western Africans, and bear little ancestry derived from the original hunter-gather populations of the broader eastern Africa region.[4]

Genetics

Most Bantus and other related Niger-Congo-speaking populations today largely carry the Y-DNA haplogroup E1b1a(E1b1a*,E1b1a7,E1b1a8). However, it has been suggested that their paternal ancestors originally belonged to the older haplogroups A and B and later acquired haplogroup E lineages through admixture with the clade's original carriers.[34]

On the mtDNA side, most Bantu peoples carry L macrohaplogroup lineages.[35]

Paleogenetic analysis of ancient fossils in eastern Africa found that present-day Bantu speakers in the region primarily trace their ancestry to a lineage related to modern western Africans, and bear little ancestry derived from the original hunter-gather populations of the broader eastern Africa region.[4]

Expansion

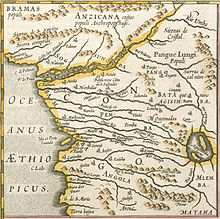

2 = ca. 1500 BC first migrations

2.a = Eastern Bantu, 2.b = Western Bantu

3 = 1000–500 BC Urewe nucleus of Eastern Bantu

4–7 = southward advance

9 = 500 BC–0 Congo nucleus

10 = 0–1000 AD last phase[36][37][38]

Current scholarly understanding places the ancestral proto-Bantu homeland in West Africa near the present-day southwestern border of Nigeria and Cameroon c. 4,000 years ago (2000 B.C.).[4][39] This view represents a resolution of debates in the 1960s over competing theories advanced by Joseph Greenberg and Malcolm Guthrie, in favor of refinements of Greenberg's theory. Based on wide comparisons including non-Bantu languages, Greenberg argued that Proto-Bantu, the hypothetical ancestor of the Bantu languages, had strong ancestral affinities with a group of languages spoken in Southeastern Nigeria. He proposed that Bantu languages had spread east and south from there, to secondary centers of further dispersion, over hundreds of years. Using a different comparative method focused more exclusively on relationships among Bantu languages, Guthrie argued for a single Central African dispersal point spreading at a roughly equal rate in all directions. Subsequent research on loanwords for adaptations in agriculture and animal husbandry and on the wider Niger–Congo language family rendered that thesis untenable. In the 1990s, Jan Vansina proposed a re-evaluation of Greenberg's ideas, in which dispersions from secondary and tertiary centers resembled Guthrie's central node idea, but from a number of regional centers rather than just one, creating linguistic clusters.[40] Vansina argued that the North-west Bantu languages near Cameroon did not split earlier than Western Bantu nor Eastern Bantu branch and that Northwest Bantu, West Bantu and East Bantu split from each other roughly at the same time, in a three-way spli.t[41] He also criticized Greenberg's lexistatics method, arguing that by its very nature the lexicostatistics technique erroneously tends to show synchronic splits as sequences.[42] Vansina argues that in general the dynamics of language differentiation in the Bantu didnot support a scenario of migration along specific routes from West Africa.[43] An application of the principle of 'least moves' yields absurd results in nearly all Bantu contexts[44] The first sign of metallurgy in the Great Lakes region, now an East Bantu-speaking area, has been dated to c. 800 B.C.[45] The migration was thought to have been prompted by an overpopulation in the Benue-Cros area, itself the consequence of an immigration from the Sahara into West Africa caused by the desiccation of the Sahara C. 2500 B.C.This whole reasoning is fatally flawed as archaeological and genetic evidence now reveals[46] Paleogenetic analysis of fossils in eastern Africa has found that the Bantu-speaking peoples likely did migrate from a homeland in Western Africa since they derive most of their ancestry from a lineage shared with modern populations in West Africa, but bear little ancestry from the ancient hunter-gatherers who originally inhabited their present area of occupation in eastern Africa.[4]

It is therefore thought that the expansion of the Bantu-speaking people from their imagined core region in West Africa began around 1000 BC. Although early models posited that the early speakers were both iron-using and agricultural, archaeology can only trace earliest use of iron from the Eastern Branch of Bantu beginning 800 BC[47]-500 BC[48].The earliest archaeological trace is found around Buhaya in Tanzania and the Kivu-Rusizi River region in Rwanda-Burundi,the well known Urewe tradition[49],though they were agricultural.[50] The western Bantu branch, not necessarily linguistically distinct, according to Christopher Ehret, followed the coast and the major rivers of the Congo system southward, reaching central Angola by around 500 BC.[51].However,there is no genetic nor archaeological evidence to support this view of Western Bantu branch migration route[52].At present the earliest archaeologically dated ceramics from the postulated western Bantu Ubangi-Congo corridor are of the Batalimo-Maluba type, dated to about 100AD at Maluba. This goes against the foundations of the theory's best fit model because it suggests Bantu speakers arrived in Great Lakes Region 900 years before they moved into Congo Basin[53]. The Urewe tradition and the Eastern Bantu seems to appear around the Great Lakes Region ‘out of the blue’ beginning 800 BC[54][55]. Urewe ware has been related to Chad, Sudan[56][57][58] and Central African Republic wares.Urewe is also the origin of all East and Southern African Bantu speaking people iron smelting techniques[59][60].The Urewe tradition arrived at the Kenyan coast in Kwale starting 0- 200 AD[61] and Lamu Manda Island by 250 AD[62].

Human populations, including hunter-gatherers and pastoralists, are known to have inhabited the area south and east of the Bantu homeland at the time of their expansion. Modern Pygmies are thought to have descended from the originally forager groups. However, mtDNA genetic research from Cabinda has found that only haplogroups which originated in West Africa exist there today and the distinctive L0 maternal haplogroup of the pre-Bantu hunter-gatherer population is missing. This suggests that there was a complete population replacement of the ancient hunter-gatherers in this area. In South Africa, a more complex intermixing could have taken place.[63]

Archaeological evidence puts Bantu presence in Central Africa rain forest beginning 100 AD.[64] Central Africa might have been populated from Great Lakes Region because Urewe tradition was fully established around the Great Lakes of East African region by 500 BC. Movements by small groups to the southeast from the Great Lakes region were more rapid, with initial settlements widely dispersed near the coast and near rivers, due to comparatively harsh farming conditions in areas further from water. Pioneering groups had reached modern KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa by A.D 300 along the coast, and the modern Limpopo Province (formerly Northern Transvaal) by A.D 500.[65][66][67]

-

A Kikuyu woman in Kenya

-

A Makua mother and child in Mozambique

-

Bubi girls in Equatorial Guinea

Kingdoms

Between the 14th and 15th centuries, Bantu states began to emerge in the Great Lakes region in the savanna south of the Central African rain-forest. In Southern Africa on the Zambezi river, the Monomatapa kings built the famous Great Zimbabwe complex, the largest of over 200 such sites in Southern Africa, such as Bumbusi in Zimbabwe and Manyikeni in Mozambique. From the 16th century onward, the processes of state formation among Bantu peoples increased in frequency. Some examples of such Bantu states include: in Central Africa, the Kingdom of Kongo,[68] Lunda Empire,[69] and Luba Empire[70] of Angola, the Republic of Congo, and the Democratic Republic of Congo; in the Great Lakes Region, the Buganda[71] and Karagwe[71] Kingdoms of Uganda and Tanzania; and in Southern Africa, the Mutapa Empire,[72] Rozwi Empire,[73] and the Danamombe, Khami, and Naletale Kingdoms of Zimbabwe and Mozambique.[72]

Toward the 18th and 19th centuries, the flow of Zanj (Bantu) slaves from Southeast Africa increased with the rise of the Omani Sultanate of Zanzibar, based in Zanzibar, Tanzania. With the arrival of European colonialists, the Zanzibar Sultanate came into direct trade conflict and competition with Portuguese and other Europeans along the Swahili Coast, leading eventually to the fall of the Sultanate and the end of slave trading on the Swahili Coast in the mid-20th century.

See also

- Bantu Educational Kinema Experiment

- Centre International des Civilisations Bantu

- Shona people

- Zulu people

- Luba people

- Sukuma people

- Kikuyu people

Notes

- ^ a b Butt, John J. (2006). The Greenwood Dictionary of World History. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 39. ISBN 0-313-32765-3.

- ^ Derek Nurse, 2006, "Bantu Languages", in the Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics

- ^ Ethnologue report for Southern Bantoid. The figure of 535 includes the 13 Mbam languages considered Bantu in Guthrie's classification and thus counted by Nurse (2006)

- ^ a b c d e Skoglund; et al. (2017). "Reconstructing Prehistoric African Population Structure". Cell. 171: 59–71. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.049. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last1=(help) - ^ Philip J. Adler, Randall L. Pouwels, World Civilizations: To 1700 Volume 1 of World Civilizations, (Cengage Learning: 2007), p.169.

- ^ Greenberg, J. (1972). Linguistic Evidence Regarding Bantu Origins. The Journal of African History, 13(2), 189-216. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/180851

- ^ Oliver, R. (1966). The Problem of the Bantu Expansion. The Journal of African History, 7(3), 361-376. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/180108

- ^ https://books.google.co.ke/books/about/Comparative_Bantu.html?id=WZZkAAAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y,pg 1-180

- ^ https://www.medievalworlds.net/0xc1aa5576_0x00348d17.pdf,pg 10

- ^ http://www.msu.ac.zw/elearning/material/temp/1329553910Vansina%201995%20linguistic%20evidence%20and%20bantu%20migrations.pdf,pg 9,11,17,18,19

- ^ Toyin Falola, Aribidesi Adisa Usman, Movements, borders, and identities in Africa, (University Rochester Press: 2009), pp.4-5.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Mary (1999). Tanzania, Zanzibar & Pemba. Lonely Planet. p. 39. ISBN 0-86442-726-3.

- ^ Peek, Philip M.; Kwesi Yankah (2004). African folklore: an encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 699. ISBN 0-415-93933-X.

- ^ Irele 2010

- ^ Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom; ARKBK CLBG. "Banyoro – Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom (Rep. Uganda) – The most powerful Kingdom in East Africa!". Retrieved 13 May 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ A comparative study of south African languages,1862 Bleek https://ia801308.us.archive.org/12/items/comparativegramm00blee/comparativegramm00blee.pdf,pg 19

- ^ The Classification of the Bantu Languages 1948 Malcolm Guthrie https://books.google.co.ke/books/about/The_Classification_of_the_Bantu_Language.html?id=pogOAAAAYAAJ&redir_esc=y,pg 1-90

- ^ https://www.britannica.com/art/Bantu-languages,pg 1

- ^ A comparative study of the Bantu and semi-Bantu languages by Johnston, Harry Hamilton, Sir, 1858-1927 https://ia902608.us.archive.org/17/items/comparativestudy01johnuoft/comparativestudy01johnuoft.pdf,pg 18

- ^ https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/dutch-settlement,pg 1

- ^ A comparative study of the Bantu and semi-Bantu languages by Johnston, Harry Hamilton, Sir, 1858-1927 https://ia902608.us.archive.org/17/items/comparativestudy01johnuoft/comparativestudy01johnuoft.pdf,pg 19

- ^ A History of the Colonization of Africa by Alien Races by Johnston, Harry Hamilton, Sir, 1858-1927 https://ia802601.us.archive.org/20/items/descriptionofcoa00barb/descriptionofcoa00barb.pdf pg 1-100

- ^ Law, Robin. “Jean Barbot as a Source for the Slave Coast of West Africa.” History in Africa, vol. 9, 1982, pp. 155–173. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3171604.

- ^ A comparative study of south African languages,1862 https://ia801308.us.archive.org/12/items/comparativegramm00blee/comparativegramm00blee.pdf,pg 1-490

- ^ A History of the Colonization of Africa by Alien Races by Johnston, Harry Hamilton, Sir, 1858-1927 https://ia800303.us.archive.org/9/items/historyofcoloniz00john/historyofcoloniz00john.pdf,pg 1-362

- ^ A History of the Colonization of Africa by Alien Races by Johnston, Harry Hamilton, Sir, 1858-1927 https://ia800303.us.archive.org/9/items/historyofcoloniz00john/historyofcoloniz00john.pdf,pg 23-26

- ^ A comparative study of the Bantu and semi-Bantu languages by Johnston, Harry Hamilton, Sir, 1858-1927 https://ia902608.us.archive.org/17/items/comparativestudy01johnuoft/comparativestudy01johnuoft.pdf,pg 18

- ^ An introduction to the study of African languages by Meinhof, Carl, 1857-1944; Werner, Alice, 1859-1935, tr; Struck, Bernhard, 1888- https://ia800204.us.archive.org/11/items/cu31924026931331/cu31924026931331.pdf,pg 40

- ^ Flight, C. (1980). Malcolm Guthrie and the Reconstruction of Bantu Prehistory. History in Africa, 7, 81-118. doi:10.2307/3171657

- ^ Greenberg, J. (1972). Linguistic Evidence Regarding Bantu Origins. The Journal of African History, 13(2), 189-216. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/180851

- ^ Vansina, J. (1995). New Linguistic Evidence and 'the Bantu Expansion'. The Journal of African History, 36(2), 173-195. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/182309

- ^ https://www.medievalworlds.net/0xc1aa5576_0x00348d17.pdf,pg 10

- ^ Oliver, R. (1966). The Problem of the Bantu Expansion. The Journal of African History, 7(3), 361-376. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/180108

- ^ "Carriers of mitochondrial DNA macrohaplogroup L3 basic lineages migrated back to Africa from Asia around 70,000 years ago". 2017. bioRxiv 233502.

{{cite bioRxiv}}: Check|biorxiv=value (help); Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Mol Biol Evol. 2011 Mar;28(3):1255-69. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq312. Epub 2010 Nov 25. Y-chromosomal variation in sub-Saharan Africa: insights into the history of Niger-Congo groups. de Filippo C1, Barbieri C, Whitten M, Mpoloka SW, Gunnarsdóttir ED, Bostoen K, Nyambe T, Beyer K, Schreiber H, de Knijff P, Luiselli D, Stoneking M, Pakendorf B.

- ^ The Chronological Evidence for the Introduction of Domestic Stock in Southern Africa Archived March 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Botswana History Page 1: Brief History of Botswana". Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ "5.2 Historischer Überblick". Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ Erhet & Posnansky, eds. (1982), Newman (1995)

- ^ Vansina, J. (1995). New Linguistic Evidence and 'the Bantu Expansion'. The Journal of African History, 36(2), 173-195. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/182309

- ^ http://www.msu.ac.zw/elearning/material/temp/1329553910Vansina%201995%20linguistic%20evidence%20and%20bantu%20migrations.pdf,pg 9

- ^ http://www.msu.ac.zw/elearning/material/temp/1329553910Vansina%201995%20linguistic%20evidence%20and%20bantu%20migrations.pdf,pg 11

- ^ http://www.msu.ac.zw/elearning/material/temp/1329553910Vansina%201995%20linguistic%20evidence%20and%20bantu%20migrations.pdf,pg 17

- ^ http://www.msu.ac.zw/elearning/material/temp/1329553910Vansina%201995%20linguistic%20evidence%20and%20bantu%20migrations.pdf,pg 18

- ^ https://www.medievalworlds.net/0xc1aa5576_0x00348d17.pdf.pg 6

- ^ Gemma Berniell-Lee, Francesc Calafell, Elena Bosch, Evelyne Heyer, Lucas Sica, Patrick Mouguiama-Daouda, Lolke van der Veen, Jean-Marie Hombert, Lluis Quintana-Murci, David Comas; Genetic and Demographic Implications of the Bantu Expansion: Insights from Human Paternal Lineages, Molecular Biology and Evolution, Volume 26, Issue 7, 1 July 2009, Pages 1581–1589, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msp06

- ^ http://www.msu.ac.zw/elearning/material/1213012109phillipson,d_1976.pdf

- ^ http://www.clist.eu/Textes/muntu-urewe.pdf

- ^ http://www.worldhistory.biz/sundries/30453-iron-age-early-and-development-of-farming-in-eastern-africa.html

- ^ Vansina, Jan (1990). Paths in the Rainforest: Toward a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-2991-2573-8.

- ^ Ehret, C. (2001). "Bantu Expansions: Re-Envisioning a Central Problem of Early African History". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 34 (1): 5–41. doi:10.2307/3097285. JSTOR 3097285.

- ^ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3561512/pdf/emss-51232.pdf

- ^ Russell, T., Silva, F., & Steele, J. (2014). Modelling the Spread of Farming in the Bantu-Speaking Regions of Africa: An Archaeology-Based Phylogeography. PLoS ONE, 9(1), e87854. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087854

- ^ M.-C. Van Grunderbeek, ‘Essai de de´limitation chronologique de l’Age du Fer Ancien au Burundi, au Rwanda et dans la re´gion des Grands Lacs’, Azania, 27 (1992), 53–80

- ^ Phillipson, African Archaeology, 251

- ^ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4915815/pdf/elife-15266.pdf,pg 19

- ^ Busby GB, Band G, Si Le Q, et al. Admixture into and within sub-Saharan Africa. Pickrell JK, ed. eLife. 2016;5:e15266. doi:10.7554/eLife.15266.

- ^ http://www.msu.ac.zw/elearning/material/temp/1213012109phillipson,d_1976.pdf,pg 78

- ^ http://www.clist.eu/Textes/muntu-urewe.pdf

- ^ http://www.ucl.ac.uk/~tcrnjst/RussellSteele2009.pdf

- ^ Southern African Humanities Vol. 21 Pages 327–344 Pietermaritzburg December, 2009

- ^ http://www.qucosa.de/fileadmin/data/qucosa/documents/9179/7_09_klein.pdf,pg 166

- ^ Beleza, Sandra; Gusmao, Leonor; Amorim, Antonio; Caracedo, Angel; Salas, Antonio (August 2005). "The Genetic Legacy of Western Bantu Migrations". Human Genetics. 117 (4): pp 366–375. doi:10.1007/s00439-005-1290-3. PMID 15928903.

{{cite journal}}:|pp=has extra text (help) - ^ https://www.belizehistorysjc.com/uploads/3/4/7/0/3470758/iron_age_in_africa.pdf

- ^ Ehret, Christopher (1998). An African Classical Age: Eastern and Southern Africa in World History, 1000 B.C. to A.D. 400. London: James Currey.[page needed]

- ^ Newman, James L. (1995). The Peopling of Africa: A Geographic Interpretation. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07280-5.[page needed]

- ^ Shillington, Kevin (2005). History of Africa (3rd ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press.[page needed]

- ^ Roland Oliver, et al. "Africa South of the Equator," in Africa Since 1800. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005, pp. 21

- ^ Roland Oliver, et al. "Africa South of the Equator," in Africa Since 1800. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005, pp. 23

- ^ Roland Oliver, et al. "Africa South of the Equator," in Africa Since 1800. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005, pp. 23.

- ^ a b Roland Oliver, et al. "Africa South of the Equator," in Africa Since 1800. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005, pp. 24-25.

- ^ a b Roland Oliver, et al. "Africa South of the Equator," in Africa Since 1800. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005, pp. 25.

- ^ Isichei, Elizabeth Allo, A History of African Societies to 1870 Cambridge University Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0-521-45599-2 page 435

References

- Christopher Ehret, An African Classical Age: Eastern and Southern Africa in World History, 1000 B.C. to A.D. 400, James Currey, London, 1998

- Christopher Ehret and Merrick Posnansky, eds., The Archaeological and Linguistic Reconstruction of African History, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1982

- April A. Gordon and Donald L. Gordon, Understanding Contemporary Africa, Lynne Riener, London, 1996

- John M. Janzen, Ngoma: Discourses of Healing in Central and Southern Africa, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1992

- James L. Newman, The Peopling of Africa: A Geographic Interpretation, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1995. ISBN 0-300-07280-5.

- Kevin Shillington, History of Africa, 3rd ed. St. Martin's Press, New York, 2005

- Jan Vansina, Paths in the Rainforest: Toward a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1990

- Jan Vansina, "New linguistic evidence on the expansion of Bantu", Journal of African History 36:173–195, 1995

External links

Media related to Bantu peoples at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bantu peoples at Wikimedia Commons