Torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person.

Torture has been carried out by states throughout history, from ancient times to the modern day. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Western countries abolished the official use of torture in the judicial system, but torture continued to be used. A variety of methods of torture are used, often in combination; the most common form of physical torture is beatings. Since the twentieth century, many torturers have preferred non-scarring or psychological methods to provide deniability. Torturers operate in a permissive organizational environment that facilitates and encourages their behavior. Reasons for torture include punishment, extracting a confession, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. Judicial corporal punishment and capital punishment are sometimes seen as forms of torture, although this is internationally controversial.

The ultimate goal of torture is to destroy the victim's agency and personality; all forms of torture can have severe physical or psychological effects on victims. Torture can also negatively affect the perpetrator and institutions. Torture is prohibited under international law for all states under all circumstances, under both international customary law and various treaties; this is often based on the argument that torture violates human dignity. Opposition to torture helped stimulate the formation of the human rights movement after World War II, and torture continues to be an important human rights issue. Although its incidence has declined, torture is still practiced by most countries and is widespread throughout the world. The primary victims of torture are poor and marginalized people suspected of ordinary crimes.

Definitions

Torture (from Latin torcere: to twist)[1] is defined as the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a victim, which is typically interpreted as someone under the control of the perpetrator.[2][3] The treatment must be inflicted for a specific purpose, such as forcing the victim to confess, provide information, or to punish them.[4][5] The United Nations Convention against Torture definition only considers torture carried out by the state.[6][7][8] Most legal systems include agents acting on behalf of the state, and some definitions would add non-state armed groups, organized crime, or private individuals working in state-monitored facilities (such as hospitals). The most expansive definitions encompass anyone as a potential perpetrator.[9] The severity threshold at which treatment can be classified as torture is the most controversial aspect of the definition of torture; over time, more actions have been considered torture.[8][6][10] The purposive approach, preferred by scholars such as Manfred Nowak and Malcolm Evans, distinguishes torture from other forms of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment by considering only the purpose for which it is applied and not the severity.[11][12] Other definitions, such as the one used in the American Convention on Human Rights, focus on the torturer's aim "to obliterate the personality of the victim".[13][14]

History

Pre-abolition

In most ancient, medieval, and early modern societies, torture was considered legally and morally acceptable and was practiced.[15] Societies used torture both as part of a judicial process and as punishment, although some authorities separate the history of torture from the history of painful punishments.[16][17] Historically, torture was seen as a reliable way to elicit the truth, a suitable punishment, and deterrence against future offenses.[18] Torture was legally regulated with strict restrictions on the allowable methods.[18] In most societies, citizens could be judicially tortured only under exceptional circumstances for a serious crime such as treason, often only when some evidence already existed. In contrast, non-citizens such as foreigners and slaves were commonly tortured.[19]

Torture was rare in early medieval Europe but became more common between 1200 and 1400.[20][21][22] Because medieval judges used an exceptionally high standard of proof, they would sometimes authorize torture where circumstantial evidence tied a person to a capital crime if there were not two eyewitnesses, as was required to convict someone in the absence of a confession.[21][22] Torture was still an expensive and labor-intensive process that was only used for the most serious crimes.[23] Most torture victims were men accused of murder, treason, or theft.[24] Medieval ecclesiastical courts and the Inquisition used torture under the same procedural rules as secular courts.[25] The Ottoman Empire and Qajar Iran used torture in cases where circumstantial evidence tied someone to a crime, even though Islamic law has traditionally considered evidence obtained under torture to be inadmissible.[26]

Abolition and continued use

During the seventeenth century, torture remained legal, but its practice declined.[27][28] By the time it was abolished, in the 18th and early 19th centuries, torture had already became of marginal importance to the criminal justice systems of European countries.[29][30] Theories for why torture was abolished include the rise of Enlightenment ideas about the value of the human person,[31][32] reduction of the standard of proof in criminal cases, popular views that no longer saw pain as morally redemptive,[27][32] and the expansion of prisons as an alternative to executions or painful punishments.[31][33] The use of torture declined after its abolition and it was increasingly seen as unacceptable.[34][35] It is not known if torture also declined in non-Western states or European colonies during the nineteenth century.[36] In China, judicial torture—practiced for more than two millennia, since the Han dynasty[18]—flogging, and lingchi (dismemberment) as a means of execution were banned in 1905.[37] Torture in China has continued throughout the twentieth and twenty-first century.[38]

Torture was widely used by colonial powers to subdue resistance; colonial torture reached a peak during the anti-colonial wars in the twentieth century.[39][40] An estimated 300,000 people were tortured during the Algerian War of Independence (1954–1962),[41] and the United Kingdom and Portugal also used torture in attempts to retain their empires.[42] Independent states in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia have often used torture in the twentieth century, but it is unknown if that is an increase over nineteenth-century levels.[39] The use of torture in Europe increased because of the invention of secret police,[43] World War I and World War II, and the rise of communist and fascist states.[15]

Torture was also used by both communist and anti-communist governments during the Cold War in Latin America, with an estimated 100,000 to 150,000 victims of torture by United States-backed regimes.[44][45] The only countries in which torture was rare during the twentieth century were the liberal democracies of the West, but even there torture was used against ethnic minorities or criminal suspects from marginalized classes, and during overseas wars against foreign populations.[39] After the 9/11 attacks, the United States government embarked on an overseas torture program as part of its "war on terror".[46] The United States' use of torture at Abu Ghraib was publicly revealed, attracting international attention.[47] Although the George W. Bush administration flouted the international prohibition of torture, it labeled its methods "enhanced interrogation techniques" and denied that they were torture.[48][49][50] A 2016 study concluded that torture had declined in 16 countries since 1985 but most likely in other countries as well, although it has worsened in others.[51]

Prevalence

Although few if any countries admit to torturing, it is practiced by most countries.[53][54] The prohibition of torture has not completely stopped states from torturing; instead, they change which techniques are used, deny, cover up, or outsource torture programs.[55] Measuring the rate at which torture occurs is difficult because it is typically committed in secrecy, and reporting such cases is affected by the human rights information paradox; abuses are more likely to come to light in open societies where there is a commitment to protecting human rights.[56] Although focus has recently shifted to include other detention sites, such as immigration detention or youth detention centers,[57][58] available estimates underrepresent torture because they do not include people who are unwilling to report as well as incidents that occur outside formal detention, in situations of extrajudicial punishment, intimidation, and crowd control.[58][59] There is even less information on the prevalence of torture before the twentieth century.[15]

Liberal democracies are less likely to abuse their citizens, but do commit abuses, including torture against marginalized citizens or especially non-citizens to whom they are not democratically accountable.[60][40] Voters may support violence against out-groups seen as threatening; majoritarian institutions are ineffective at preventing torture against minorities or foreigners.[61] Significant political changes, such as a transition to democracy, are often cited as the reason for changes in the incidence of torture.[62] Torture is more likely when a society feels threatened because of wars or crises,[60][61] but studies have not been able to draw a consistent connection between the use of torture and terrorist attacks.[63]

Torture is directed against certain segments of the population, who are denied the protection against torture that others enjoy.[64][65][61] Torture of political prisoners or during armed conflict has received a disproportionate amount of attention.[66][56] Most victims of torture are suspected of crimes; a disproportionate number of victims are from poor or marginalized communities, especially unemployed young men, the urban poor, and LGBT people.[67][56] Other groups especially vulnerable to torture include refugees and migrants, ethnic or racial minorities, indigenous people, and people with disabilities.[68] Routine violence against poor and marginalized people is often not seen as torture, and its perpetrators justify the violence as legitimate policing tactic.[69] Criminalization of homelessness, sex work, or working in the informal economy can provide an excuse for police violence against the poor.[70] Torture is perceived as an exceptional event, disregarding this routine state violence.[71][72]

Perpetration

Many torturers see their actions as serving a higher political or ideological goal that justifies torture as a legitimate means of protecting the state.[73][74][61] Torture cultures value self-control, discipline, and professionalism as positive values, helping torturers to maintain a positive self-image.[74] Torturers who inflict more suffering than necessary to break the victim or act out of impermissible motives (revenge, sexual gratification) are rejected by peers or relieved of duty.[75] Torture victims are often viewed by the perpetrators as serious threats and enemies of the state.[76] Philosopher Jessica Wolfendale argues that since "the decision to torture a person involves a refusal to see the victim's status as a person as setting limits on what may be done to them", its victims are already seen as less than fully human before they are tortured.[64] Psychiatrist Pau Pérez-Sales finds that a torturer could act from a variety of motives such as ideological commitment, personal gain, group belonging, avoiding punishment, or avoiding guilt from previous acts of torture.[77]

A combination of dispositional and situational efforts lead a person to become a torturer.[77] In most cases where torture is used systematically, the torturers were desensitized to violence by being exposed to physical or psychological abuse during training.[78][79][80] Wolfendale argues that military training aims to inculcate unquestioning obedience, therefore making military personnel more likely to become torturers.[81] Even when torture is not explicitly ordered by the government,[82] perpetrators may feel peer pressure to torture because refusing is seen as weak or unmanly.[83] Elite and specialized police units are especially prone to torturing, perhaps because of their tight-knit nature and insulation from oversight.[82]

Torture can be a side effect of a broken criminal justice system in which underfunding, lack of judicial independence, or corruption undermines effective investigations and fair trials.[84][85] In this context, poor or marginalized people who cannot afford bribes are likely to become victims of torture.[86][85] Police that are understaffed or poorly trained are more likely to resort to torture when interrogating suspects.[87][88] In some countries, such as Kyrgyzstan, suspects are more likely to be tortured at the end of the month because of performance quotas.[87]

Torture perpetrators would not be able to continue without the support of others who actively support its occurrence and many bystanders who ignore torture.[89] Military, intelligence, psychology, medical, and legal professionals can help build a torture culture.[74] Incentives can favor the use of torture on an institutional or individual level; some perpetrators are motivated by the prospect of career advancement.[90][91] The bureaucracy diffuses responsibility for torture, helping perpetrators excuse their actions.[78][92] Maintaining secrecy and keeping abuses hidden from the public is often essential to maintaining a torture program, which can be accomplished in different ways, ranging from direct censorship, denial or mislabeling torture as something else, to offshoring abuses outside the state territory.[93][94] Along with official denials, torture is fueled by moral disengagement from the victims and impunity (non-prosecution) for the perpetrators[61]—criminal prosecutions for torture are rare.[95]

Torture is difficult or impossible to contain, extending to more severe techniques and larger groups of victims beyond what is originally intended or desired by high-level decision-makers.[96][97][98] Escalation of torture is especially difficult to contain in counterinsurgency operations.[83] Torture and specific torture techniques spread between different countries, especially by soldiers returning home from overseas wars, but this process is poorly understood.[99][100]

Purpose

Punishment

Torture for punishment dates back to antiquity, and is still employed in the 21st century.[16] In some countries where the justice system is dysfunctional, it is common for the police to enact instant punishment on young men and release them without a charge.[101] Such torture could be performed in a police station[102] the victim's home, or a public place.[103]

The classification of judicial corporal punishment as torture is internationally controversial, although it is explicitly prohibited under the Geneva Conventions.[104] Some authors, such as John D. Bessler, argue that capital punishment is inherently a form of torture carried out for punishment.[105][106] Executions may be carried out in brutal ways, such as stoning, death by burning, or dismemberment.[107] In early modern Europe, public executions were a way of demonstrating state power, inspiring awe and obedience, and deterring others from doing the same.[108] The psychological harm of capital punishment, for example, the death row phenomenon, is sometimes considered a form of psychological torture.[109] Others distinguish corporal punishment with a fixed penalty from torture, as it does not seek to break the victim's will.[110]

Deterrence

Torture may also be used indiscriminately to terrorize people other than the direct victim or deter opposition to the government.[111] Torture was used to deter slaves from escaping or rebelling.[112] Some defenders of judicial torture prior to its abolition saw it as a useful means of deterring crime; reformers argued that because torture was carried out it secret, it could not be an effective deterrent.[113] In the twentieth century, well-known examples include the Khmer Rouge[111] and anti-communist regimes in Latin America, who often tortured and murdered their victims as part of forced disappearance.[114] Regimes that are otherwise weak are more likely to resort to torture to deter opposition;[115] many authoritarian regimes are ineffective at locating potential opponents, leading to indiscriminate repression.[116] Although some insurgencies also use torture, many lack the infrastructure necessary for a torture program and instead intimidate by killing.[117] Research has found that state torture can extend the lifespan of terrorist organizations, increase incentives for insurgents to use violence, and radicalize the opposition.[118] Researchers James Worrall and Victoria Penziner Hightower argue that the Syrian government's systematic torture during the Syrian civil war shows that the widespread use can be effective in instilling fear into certain groups or neighborhoods during a civil war.[119] Another form of torture for deterrence is violence against migrants, as has been reported during pushbacks on the European Union's external borders.[120]

Confession

Throughout history, torture has been used to extract a confession from detainees. In 1764, Italian reformer Cesare Beccaria denounced torture as "a sure way to acquit robust scoundrels and to condemn weak but innocent people".[18][121] Similar doubts about torture's effectiveness were voiced for centuries previously, including by Aristotle.[122][123] Despite the abolition of judicial torture, torture to elicit a confession continues to be used, especially in judicial systems placing a high value on confessions in criminal matters.[124][125] The use of torture to force suspects to confess is facilitated by laws allowing extensive pre-trial detention.[126] Research has found that coercive interrogation is slightly more effective than cognitive interviewing for extracting a confession from a suspect, but at a higher risk of false confession.[127] Many torture victims will say whatever the torturer wants to hear to end the torture.[128][129] Others who are guilty refuse to make a confession under torture,[130] especially if they believe that confessing will only bring more torture or punishment.[125] Medieval justice systems attempted to safeguard against the risk of false confession under torture by requiring those who confessed to provide details about the crime that could be falsified and only allowing torture if there was already some evidence against the accused.[131][24] In some countries, political opponents are tortured to force them to confess publicly as a form of state propaganda. This tactic was used in Eastern Bloc show trials and in Iran.[124]

Interrogation

The use of torture to obtain information during interrogation accounts for a small percentage of torture cases in the world; the use of torture for obtaining confessions or intimidation is more common.[132] Although interrogational torture has been used in conventional wars, it is even more common in asymmetric war or non-international armed conflict.[124] The ticking time bomb scenario is extremely rare, if not impossible in the real world,[56][133] but is cited to justify torture for interrogation. Fictional portrayals of torture as an effective interrogational method have fuelled misconceptions that justify the use of torture.[134] Experiments testing whether torture is more effective than other interrogation methods cannot be performed for ethical and practical reasons.[135][136][137] Most scholars of torture are skeptical about its efficacy in obtaining accurate information, although torture sometimes has obtained actionable intelligence.[138][139] Interrogational torture can often shade into confessional torture or simply into entertainment;[140] some torturers do not distinguish between interrogation and confession.[137]

Methods

Torture has been accomplished through a wide variety of techniques used throughout history and across the world.[141] Nevertheless, there are striking similarities in torture methods because there are a limited number of ways of inflicting pain while minimizing the risk of death.[142] Survivors report that the exact method used is not significant.[143] Most forms of torture include both physical and psychological elements,[144][145] and in most cases, multiple methods are combined.[146] Different methods of torture are popular in different countries.[147] Low-tech methods are more commonly used than high-tech ones and attempts to develop scientifically validated torture technology have been failures.[148] The prohibition of torture has motivated a shift to ones that do not leave marks to make torture more palatable for the torturer or the public, hide it from the media, and deprive victims of legal redress.[149][150] As they faced more pressure and scrutiny, democracies led the innovation in torture practices.[151][18] The patterns of how torture is perpetrated differ based on the time limits faced by the torturer, for example due to legal limits on pre-trial detention.[152]

Beatings or blunt trauma are the most common form of physical torture.[153] They may be either unsystematic[154] or focused on a specific part of the body, as in falanga (the soles of the feet), repeated strikes against both ears, or shaking the detainee so that their head moves back and forth.[155] Often, people are suspended in painful positions such as Palestinian hanging or upside-down hanging in combination with beatings.[156] People may also be subjected to stabbings or puncture wounds, have their nails removed, or body parts amputated.[157] Burns are also common, especially cigarette burns, but other instruments are also used, including hot metal, hot fluids, the sun, or acid.[158] Forced ingestion of various substances, including water, food, or other substances, or injections are also used as forms of torture.[159] Electric shocks are often used to torture, especially to avoid other methods that are more likely to leave scars.[160] Asphyxiation (including waterboarding) inflicts torture on the victim by cutting off their air supply.[157]

Psychological torture includes methods that involve no physical element, others that consist of no-touch physical manipulation of the body, and physical attacks that ultimately target the mind.[144] Death threats, mock execution, or being forced to witness the torture of another person are often reported to be subjectively worse than being physically tortured and are associated with severe sequelae.[161] Other torture techniques include sleep deprivation, overcrowding or solitary confinement, withholding food or water, sensory deprivation (such as hooding), exposure to extremes of light or noise (e.g. musical torture), and humiliation.[162] Positional torture works by forcing the person to adopt a stance, putting their weight on a few muscles, causing pain without leaving marks, for example standing or squatting for extended periods.[163] Rape and sexual assault are often remembered by survivors as the worst form of torture.[164]

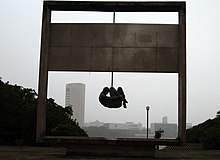

Effects

Torture is one of the most devastating experiences that a person can encounter.[165] Torture aims to break the victim's will[166] and destroy the victim's agency and personality.[167] Torture survivor Jean Améry argued that it was "the most horrible event a human being can retain within himself"; he insisted that "whoever was tortured, stays tortured".[168][169] Many torture victims, including Améry, have died by suicide.[170] Survivors often experience social and financial problems.[171] Current circumstances, such as housing insecurity, family separation, and the uncertainty of applying for asylum in a safe country, strongly impact survivors' well-being.[172]

Death is not an uncommon outcome of torture.[173] Health consequences can include peripheral neuropathy, damage to teeth, rhabdomyolysis from extensive muscle damage,[153] traumatic brain injury,[174] sexually transmitted infection, and pregnancy from rape.[175] Chronic pain and pain-related disability are commonly reported, but there is very little research into this effect or possible treatments.[176] Common psychological effects of torture on survivors include traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance.[177][171] Uncontrolled studies on torture survivors have found that between 15 and 85 percent meet the diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), with a higher risk for psychological torture compared to physical torture.[178] Torture causes a higher risk of traumatic sequelae than any other known human experience.[165] Although the traditional view is that fear causes trauma, Pérez-Sales argues that loss of control explains trauma in torture survivors.[179] As torture is a form of political violence, not all survivors or rehabilitation experts support using medical categories to define their experience,[180] and many survivors experience psychological resilience.[181]

Survivors of torture, their families, and others in the community may require long-term material, medical, psychological and social support.[182] Most torture survivors do not disclose unless specifically asked by a healthcare provider.[183] Psychological interventions have shown a statistically significant but clinically minor decrease in PTSD symptoms which did not persist at follow-up. Other outcomes, such as psychological distress or quality of life, showed no benefit or were not measured.[184] Most studies have narrowly focused on PTSD symptoms, and there is a lack of research on integrated or patient-centric approaches.[185]

Although there is less research on the effects of torture on perpetrators,[186] they can experience moral injury or trauma symptoms similar to the victims'—especially when they feel guilty about their actions.[187][188] Torture has corrupting effects on the institutions and societies that perpetrate it and erodes professional competence. Torturers forget important investigative skills because torture can be an easier way to achieve high conviction rates through coerced and often false confessions than time-consuming police work. This deskilling encourages the continued and increased use of torture.[189][187][190] Public disapproval of torture can harm the international reputation of countries that use torture, radicalize the opposition, strengthen violent opposition to the torturing state,[191][192][193] and encourage the adversary to themselves use torture.[194]

Public opinion

Studies have found that most people in different countries around the world oppose the use of torture in general[195][196] but a minority is willing to justify its use in specific cases.[196] Some people hold categorical views on torture, while for others torture's acceptability depends on the context,[197] with more people willing to authorize torture against someone described as a terrorist, Muslim, or culpable.[198] Support for torture in specific cases is correlated with inaccurate beliefs about the effectiveness of torture or scenarios such as the ticking time-bomb scenario that do not reflect how torture is used in practice.[199] Nonreligious people are less likely to support the use of torture than religious people. For people who identify with a religion, increased religiosity increases opposition to torture.[200] Public opinion is an important constraint on the use of torture by states, and opposition to torture can increase following the experience of political repression.[201] On the other hand, when the public supports torture against certain segments of the population, such as drug addicts or criminal suspects, this can facilitate the use of torture.[65]

Prohibition

In the contemporary world, torture is nearly universally regarded as abhorrent.[202] Torture is criticized on the basis of all major ethical frameworks, including deontology, consequentialism, and virtue ethics.[203][204] Some contemporary philosophers argue that torture is never morally acceptable, while others propose exceptions to the general rule in real-life equivalents of the ticking time bomb scenario.[202][205] The taboo against torture, classifying it as barbaric and cruel, developed from the debates around its abolition.[206] By the late nineteenth century, countries began to be condemned internationally for the use of torture,[207] and international norms required torture to be prevented and punished—even if committed against colonized people.[208] The taboo was strengthened during the twentieth century in reaction to the use of torture by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, which was widely condemned despite these regimes' secrecy and denial.[209] Shocked by Nazi atrocities during World War II, the United Nations drew up the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which prohibited torture.[210][211]

Torture was the primary issue that stimulated the creation of the human rights movement.[212] In 1969, the Greek case was the first time that an international body (the European Commission on Human Rights) found that a state practiced torture.[213] In the early 1970s, Amnesty International launched a global campaign against torture, exposing its widespread use despite international prohibition, and eventually leading to the United Nations Convention against Torture (CAT) in 1984.[214] Successful civil society mobilizations against torture can prevent its use by governments that possess both motive and opportunity to use torture.[215] Torture remains central to the human rights movement in the twenty-first century.[216]

The prohibition of torture is a peremptory norm in international law, meaning that it is forbidden for all states under all circumstances.[217][218] Most jurists justify the absolute legal prohibition on torture based on its violation of human dignity.[219] The CAT and its Optional Protocol focus on the prevention of torture, which was already prohibited in international human rights law under other treaties such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.[220][221] The CAT specifies that evidence obtained under torture may not be admitted in court and deporting a person to another country where they are likely to face torture is forbidden (this is also illegal under international customary law).[218] Even though it is illegal under national law, judges in many countries continue to admit evidence obtained under torture or ill-treatment.[222][223] A 2009 study found that 42 percent of parties of the CAT continue to use torture systematically.[61]

In international humanitarian law applicable during armed conflicts, torture was first outlawed by the 1863 Lieber Code.[224] Torture was prosecuted during the Nuremberg trials as a crime against humanity.[225] Torture is recognized by both the 1949 Geneva Conventions and the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court as a war crime.[226][227] According to the Rome Statute, torture can also be a crime against humanity if committed as part of a systematic attack on a civilian population.[228]

Prevention

Torture is a crime of opportunity and proliferates in situations of incommunicado detention.[229][230] The risk of torture can be effectively eliminated with the right safeguards, at least in peacetime.[231][232] A 2016 study commissioned by the Association for the Prevention of Torture found that the single strongest measure that correlated with rates of torture was practices of detention.[230][233] Because the risk of torture is highest directly after an arrest, procedural safeguards such as immediate access to a lawyer and notifying relatives about an arrest are the most effective ways of preventing torture.[234] Visits by independent monitoring bodies to sites of detention can also help reduce the incidence of torture.[235] Because legal provisions may not be applied in practice, practice correlates much better with the incidence of torture than legal rights.[236]

Sociologically, torture operates as a subculture, frustrating prevention efforts because torturers can find a way around rules.[237] Safeguards against torture in detention can be evaded by beating suspects during roundups or on the way to the police station.[238][239] General training of police to improve their ability to investigate crime has been more effective at reducing torture than specific training focused on human rights.[240][241] Institutional police reforms have been effective when abuses are systematic.[242][243] Rejali criticizes torture prevention research for not figuring out "what to do when people are bad; institutions broken, understaffed, and corrupt; and habitual serial violence is routine".[231]

References

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, p. 326.

- ^ Nowak 2014, pp. 396–397.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, p. 38.

- ^ Nowak 2014, pp. 394–395.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, pp. 96–97.

- ^ a b Carver & Handley 2016, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Nowak 2014, p. 392.

- ^ a b Hajjar 2013, p. 40.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, pp. 279–280.

- ^ Saul & Flanagan 2020, pp. 364–365.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, p. 37.

- ^ Nowak 2014, p. 391.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, pp. 3, 281.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, pp. 73–74.

- ^ a b c Einolf 2007, p. 104.

- ^ a b Hajjar 2013, p. 14.

- ^ Barnes 2017, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b c d e Evans 2020, History of Torture.

- ^ Einolf 2007, p. 107.

- ^ Beam 2020, p. 392.

- ^ a b Einolf 2007, pp. 107–108.

- ^ a b Hajjar 2013, p. 16.

- ^ Beam 2020, pp. 398, 405.

- ^ a b Beam 2020, p. 394.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, p. 34.

- ^ Einolf 2007, p. 108.

- ^ a b Einolf 2007, p. 109.

- ^ Beam 2020, p. 400.

- ^ Einolf 2007, pp. 104, 109.

- ^ Beam 2020, p. 404.

- ^ a b Hajjar 2013, p. 19.

- ^ a b Wisnewski 2010, p. 25.

- ^ Beam 2020, pp. 399–400.

- ^ Einolf 2007, p. 110.

- ^ Barnes 2017, p. 47.

- ^ Einolf 2007, p. 111.

- ^ Bourgon 2003, p. 851.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, p. 155.

- ^ a b c Einolf 2007, p. 112.

- ^ a b Hajjar 2013, p. 24.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Barnes 2017, p. 94.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, p. 38.

- ^ Einolf 2007, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, p. 7.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Saul & Flanagan 2020, pp. 357–358.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, p. 39.

- ^ Kelly 2019, p. 2.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, p. 42.

- ^ Barnes 2017, p. 182.

- ^ a b c d Carver & Handley 2016, p. 36.

- ^ Rejali 2020, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b Kelly 2019, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Jensena et al. 2017, pp. 406–407.

- ^ a b Einolf 2007, p. 106.

- ^ a b c d e f Evans 2020, Political and Institutional Influences on the Practice of Torture.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, p. 47.

- ^ Rejali 2020, p. 82.

- ^ a b Wolfendale 2019, p. 89.

- ^ a b Celermajer 2018, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Oette 2021, p. 307.

- ^ Kelly 2019, pp. 5, 7.

- ^ Oette 2021, p. 321.

- ^ Celermajer 2018, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Oette 2021, pp. 329–330.

- ^ Oette 2021, p. 308.

- ^ Jensena et al. 2017, p. 405.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, pp. 192–193.

- ^ a b c Wolfendale 2019, p. 92.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, pp. 194–195.

- ^ a b Pérez-Sales 2016, p. 106.

- ^ a b Collard 2018, p. 166.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Celermajer 2018, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, p. 193.

- ^ a b Wisnewski 2010, pp. 193–194.

- ^ a b Rejali 2020, p. 90.

- ^ Celermajer 2018, p. 178.

- ^ a b Carver & Handley 2016, p. 633.

- ^ Celermajer 2018, p. 161.

- ^ a b Carver & Handley 2016, p. 79.

- ^ Celermajer 2018, p. 176.

- ^ Huggins 2012, pp. 47, 54.

- ^ Huggins 2012, p. 62.

- ^ Rejali 2020, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Huggins 2012, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Huggins 2012, pp. 57, 59–60.

- ^ Evans 2020, Conclusion.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, pp. 84–86, 88.

- ^ Hassner 2020, pp. 18–20.

- ^ Wolfendale 2019, pp. 89–90, 92.

- ^ Rejali 2020, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Collard 2018, pp. 158, 165.

- ^ Rejali 2020, pp. 75, 82–83, 85.

- ^ Oette 2021, p. 331.

- ^ Celermajer 2018, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Jensena et al. 2017, pp. 403, 407.

- ^ Nowak 2014, pp. 408–409.

- ^ Nowak 2014, p. 393.

- ^ Bessler 2018, p. 3.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, pp. 414, 422, 427.

- ^ Beam 2020, p. 395.

- ^ Bessler 2018, p. 33.

- ^ Evans 2020, The Definition of Torture.

- ^ a b Hajjar 2013, p. 23.

- ^ Young & Kearns 2020, p. 7.

- ^ Barnes 2017, pp. 26, 38, 41.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, p. 28.

- ^ Worrall & Hightower 2021, p. 4.

- ^ Blakeley 2007, p. 392.

- ^ Rejali 2009, p. 38.

- ^ Hassner 2020, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Worrall & Hightower 2021, pp. 7–8, 10.

- ^ Guarch-Rubio et al. 2020, pp. 69, 78.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, p. 26.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Barnes 2017, p. 40.

- ^ a b c Hajjar 2013, p. 22.

- ^ a b Einolf 2022, p. 11.

- ^ Rejali 2009, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, p. 327.

- ^ Hassner 2020, p. 16.

- ^ Rejali 2009, pp. 461–462.

- ^ Rejali 2009, p. 362.

- ^ Barnes 2017, p. 28.

- ^ Rejali 2020, p. 92.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, p. 4.

- ^ Rejali 2020, pp. 92–93, 106.

- ^ Houck & Repke 2017, pp. 277–278.

- ^ Hassner 2020, p. 24.

- ^ a b Einolf 2022, p. 2.

- ^ Einolf 2022, p. 3.

- ^ Rejali 2020, p. 71.

- ^ Hassner 2020, pp. 16, 20.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, p. 410.

- ^ Einolf 2007, p. 103.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, p. 110.

- ^ a b Pérez-Sales 2020, p. 432.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, p. 8.

- ^ Rejali 2009, p. 421.

- ^ Rejali 2009, p. 420.

- ^ Rejali 2009, pp. 440–441.

- ^ Rejali 2009, p. 443.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, p. xix.

- ^ Rejali 2020, p. 73.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, pp. 271–272.

- ^ a b Quiroga & Modvig 2020, p. 413.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, p. 411.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, pp. 413–414.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, pp. 414–415.

- ^ a b Quiroga & Modvig 2020, pp. 418–419.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, pp. 421–422.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, p. 423.

- ^ Einolf 2007, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, pp. 426–427.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, pp. 424–425.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, pp. 415–416.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, p. 52.

- ^ a b Pérez-Sales 2016, p. 274.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, p. 73.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, p. 51.

- ^ Shue 2015, p. 120.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, pp. 121–122.

- ^ a b Hamid et al. 2019, p. 3.

- ^ Williams & Hughes 2020, pp. 133–134, 137.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, p. 428.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, p. 412.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, p. 422.

- ^ Williams & Hughes 2020, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Williams & Hughes 2020, p. 136.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, p. 130.

- ^ "Rehabilitation of Torture Victims". International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ Williams & Hughes 2020, p. 135.

- ^ Hamid et al. 2019, p. 10.

- ^ Hamid et al. 2019, p. 11.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, pp. 53–55.

- ^ a b Rejali 2020, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Hassner 2020, p. 23.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, p. 166.

- ^ Saul & Flanagan 2020, p. 370.

- ^ Blakeley 2007, pp. 390–391.

- ^ Hassner 2020, p. 22.

- ^ Hassner 2020, p. 21.

- ^ Rejali 2020, p. 81.

- ^ a b Houck & Repke 2017, p. 279.

- ^ Hatz 2021, p. 683.

- ^ Hatz 2021, p. 689.

- ^ Houck & Repke 2017, pp. 276–277.

- ^ Hatz 2021, p. 688.

- ^ Rejali 2020, pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b Wisnewski 2010, p. 50.

- ^ Hassner 2020, p. 29.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Shue 2015, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Barnes 2017, pp. 14, 42.

- ^ Barnes 2017, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Barnes 2017, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Barnes 2017, p. 57.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Barnes 2017, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, p. 41.

- ^ Barnes 2017, p. 121.

- ^ Barnes 2017, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Collard 2018, p. 162.

- ^ Kelly 2019, p. 1.

- ^ Evans 2020, Introduction.

- ^ a b Saul & Flanagan 2020, p. 356.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, p. 82.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, p. 13.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, p. 39.

- ^ Thomson & Bernath 2020, pp. 474–475.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, p. 631.

- ^ Nowak 2014, pp. 387, 401.

- ^ Barnes 2017, pp. 60, 70.

- ^ Nowak 2014, p. 398.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, p. 38.

- ^ Nowak 2014, pp. 397–398.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b Thomson & Bernath 2020, p. 472.

- ^ a b Rejali 2020, p. 102.

- ^ Thomson & Bernath 2020, p. 492.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, p. 66.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, p. 67–68.

- ^ Thomson & Bernath 2020, pp. 482–483.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, p. 52.

- ^ Rejali 2020, p. 101.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Kelly 2019, p. 4.

- ^ Thomson & Bernath 2020, p. 488.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, p. 80.

- ^ Kelly 2019, p. 8.

Sources

Books

- Barnes, Jamal (2017). A Genealogy of the Torture Taboo. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-97773-9.

- Carver, Richard; Handley, Lisa (2016). Does Torture Prevention Work?. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-78138-868-6.

- Celermajer, Danielle (2018). The Prevention of Torture: An Ecological Approach. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-63389-5.

- Collard, Melanie (2018). Torture as State Crime: A Criminological Analysis of the Transnational Institutional Torturer. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-45611-9.

- Hajjar, Lisa (2013). Torture: A Sociology of Violence and Human Rights. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-51806-2.

- Pérez-Sales, Pau (2016). Psychological Torture: Definition, Evaluation and Measurement. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-20647-7.

- Rejali, Darius (2009). Torture and Democracy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3087-9.

- Wisnewski, J. Jeremy (2010). Understanding Torture. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-8672-8.

- Young, Joseph K.; Kearns, Erin M. (2020). Tortured Logic: Why Some Americans Support the Use of Torture in Counterterrorism. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-54809-0.

Book chapters

- Beam, Sara (2020). "Violence and Justice in Europe: Punishment, Torture and Execution". The Cambridge World History of Violence: Volume 3: AD 1500–AD 1800. Cambridge University Press. pp. 389–407. ISBN 978-1-107-11911-6.

- Evans, Rebecca (2020). "The Ethics of Torture: Definitions, History, and Institutions". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-084662-6.

- Nowak, Manfred (2014). "Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment". The Oxford Handbook of International Law in Armed Conflict. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-163269-3.

- Pérez-Sales, Pau (2020). "Psychological torture". Research Handbook on Torture: Legal and Medical Perspectives on Prohibition and Prevention. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 432–454. ISBN 978-1-78811-396-0.

- Quiroga, José; Modvig, Jens (2020). "Torture methods and their health impact". Research Handbook on Torture: Legal and Medical Perspectives on Prohibition and Prevention. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 410–431. ISBN 978-1-78811-396-0.

- Rejali, Darius (2020). "The Field of Torture Today: Ten Years On from Torture and Democracy". Interrogation and Torture: Integrating Efficacy with Law and Morality. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-009752-3.

- Saul, Ben; Flanagan, Mary (2020). "Torture and counter-terrorism". Research Handbook on International Law and Terrorism. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 354–370. ISBN 978-1-78897-222-2.

- Shue, Henry (2015). "Torture". The Routledge Handbook of Global Ethics. Routledge. pp. 113–126. ISBN 978-1-315-74452-0.

- Thomson, Mark; Bernath, Barbara (2020). "Preventing Torture: What Works?". Interrogation and Torture: Integrating Efficacy with Law and Morality. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-009752-3.

- Wolfendale, Jessica (2019). "The Making of a Torturer". The Routledge International Handbook of Perpetrator Studies. Routledge. pp. 84–94. ISBN 978-1-315-10288-7.

Journal articles

- Bessler, John D. (2018). "The Abolitionist Movement Comes of Age: From Capital Punishment as Lawful Sanction to a Peremptory, International Law Norm Barring Executions". Montana Law Review. 79: 7–48. ISSN 0026-9972.

- Bourgon, Jérôme (2003). "Abolishing 'Cruel Punishments': A Reappraisal of the Chinese Roots and Long-term Efficiency of the Xinzheng Legal Reforms". Modern Asian Studies. 37 (4): 851–862. doi:10.1017/S0026749X03004050.

- Blakeley, Ruth (2007). "Why torture?" (PDF). Review of International Studies. 33 (3): 373–394. doi:10.1017/S0260210507007565.

- Einolf, Christopher J. (2007). "The Fall and Rise of Torture: A Comparative and Historical Analysis". Sociological Theory. 25 (2): 101–121. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9558.2007.00300.x.

- Einolf, Christopher J (2022). "How Torture Fails: Evidence of Misinformation from Torture-Induced Confessions in Iraq". Journal of Global Security Studies. 7 (1). doi:10.1093/jogss/ogab019.

- Guarch-Rubio, Marta; Byrne, Steven; Manzanero, Antonio L. (2020). "Violence and torture against migrants and refugees attempting to reach the European Union through Western Balkans". Torture Journal. 30 (3): 67–83. doi:10.7146/torture.v30i3.120232. ISSN 1997-3322.

- Hamid, Aseel; Patel, Nimisha; Williams, Amanda C. de C. (2019). "Psychological, social, and welfare interventions for torture survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". PLOS Medicine. 16 (9): e1002919. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002919. PMC 6759153. PMID 31550249.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Hassner, Ron E. (2020). "What Do We Know about Interrogational Torture?". International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence. 33 (1): 4–42. doi:10.1080/08850607.2019.1660951.

- Hatz, Sophia (2021). "What Shapes Public Support for Torture, and Among Whom?". Human Rights Quarterly. 43 (4): 683–698. doi:10.1353/hrq.2021.0055.

- Houck, Shannon C.; Repke, Meredith A. (2017). "When and why we torture: A review of psychology research". Translational Issues in Psychological Science. 3 (3): 272–283. doi:10.1037/tps0000120.

- Huggins, Martha K. (2012). "State Torture: Interviewing Perpetrators, Discovering Facilitators, Theorizing Cross-Nationally - Proposing "Torture 101"". State Crime Journal. 1 (1): 45–69. ISSN 2046-6056.

- Jensena, Steffen; Kelly, Tobias; Andersen, Morten Koch; Christiansen, Catrine; Sharma, Jeevan Raj (2017). "Torture and Ill-Treatment Under Perceived: Human Rights Documentation and the Poor". Human Rights Quarterly. 39 (2): 393–415. doi:10.1353/hrq.2017.0023. ISSN 1085-794X.

- Kelly, Tobias (2019). "The Struggle Against Torture: Challenges, Assumptions and New Directions". Journal of Human Rights Practice. 11 (2): 324–333. doi:10.1093/jhuman/huz019.

- Oette, Lutz (2021). "The Prohibition of Torture and Persons Living in Poverty: From the Margins to the Centre". International & Comparative Law Quarterly. 70 (2): 307–341. doi:10.1017/S0020589321000038. ISSN 0020-5893.

- Williams, Amanda C. de C.; Hughes, John (2020). "Improving the assessment and treatment of pain in torture survivors". BJA Education. 20 (4): 133–138. doi:10.1016/j.bjae.2019.12.003. PMC 7807909. PMID 33456942.

- Worrall, James; Hightower, Victoria Penziner (2021). "Methods in the madness? Exploring the logics of torture in Syrian counterinsurgency practices". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies: 1–15. doi:10.1080/13530194.2021.1916154.