Free Willy

| Free Willy | |

|---|---|

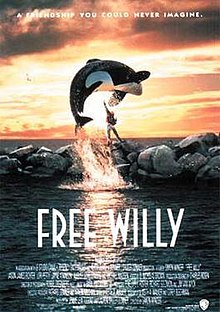

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Simon Wincer |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Keith A. Walker |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robbie Greenberg |

| Edited by | O. Nicholas Brown |

| Music by | Basil Poledouris |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 112 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $20 million |

| Box office | $153.7 million[1] |

Free Willy is a 1993 American family drama film, directed by Simon Wincer, produced by Lauren Shuler Donner and Jennie Lew Tugend, written by Keith A. Walker and Corey Blechman from a story by Walker and distributed by Warner Bros. Pictures under their Family Entertainment imprint. The film stars Jason James Richter in his feature film debut, Lori Petty, Jayne Atkinson, August Schellenberg, and Michael Madsen with the eponymous character, Willy, played by Keiko. The story is about an orphaned boy who befriended a captive orca at an ailing amusement park.

Released on July 16, 1993, the film received positive attention from critics and was a commercial success, grossing $153.7 million from a $20 million budget.

It grew into a small franchise, including an animated television series, two sequels and a direct-to-video reboot in addition to inspiring the rehabilitation and release of Keiko. It was the first and only film written by Keith A. Walker, a writer, producer, and actor on various projects, who died in December of 1996.

Plot

Near the coastline of the Pacific Northwest, a pod of killer whales is peacefully swimming. The pod is tracked down by a group of whalers. One of the orcas has a distinguishable set of three spots. The orca gets trapped and sent to the Northwest Adventure Park while his family is unable to help.

Months later in Portland, Oregon, Jesse, a troubled 12-year-old abandoned by his estranged mother six years earlier, spent three days in the streets after fleeing from Cooperton until police catch him and Perry, who escaped, vandalizing the park's observation room where Jesse encountered the orca named Willy. Jesse's social worker Dwight earns him a reprieve by having him clean up the graffiti despite his placement with the Greenwoods remaining intact. His foster parents are the supportive and kind Annie and Glen Greenwood, but Jesse is initially unruly and hostile to them.

Jesse sees Willy again. Willy, who is regarded as surly and uncooperative by Rae Lindley, later takes a liking to Jesse's harmonica-playing and later saves him from drowning. The two start a bond and Jesse also becomes friendly with Willy's keeper Randolph Johnson. Randolph teaches him about his connection with Willy, and Jesse is offered a summer job after probation, and also warms up to his new home.

Park owner Dial sees the talent Jesse and Willy have together in hopes of finally making money from Willy who has thus far been a costly venture for him. On opening day, however, Willy refuses to perform due to being antagonized. Jesse, unable to get him to do tricks while dealing with pressure from spectators, tearfully storms off and plans to find his mother. Willy cracks the tank with his stress-induced rage, having had enough of the children's constant banging. Later that night, Jesse says farewell but notices Willy's family calling to him from the outside and realizes how miserable he is in captivity after discovering their voices responding to Willy's cry. However, the discovery is cut short when Jesse spots Wade and several colleagues sneaking into the observation area to deliberately damage the tank enough that the water will gradually leak out and kill Willy, allowing them to cash in on $1,000,000 of insurance.

After Randolph reveals Dial's plan, Jesse hatches an idea to free Willy and also recruited Rae. They steal Glen's truck, then use the forklift to load Willy onto a trailer attached to the truck and tow him to Dawson's Marina. Dial launches a search after Wade called him about Willy being stolen. Jesse, Randolph, and Rae try to stay on the back roads to avoid being spotted, but eventually get stuck in the mud.

With Randolph and Rae unable to move the trailer, Jesse calls Glen and Annie using a CB radio in the truck. Glen and Annie show up and help free the truck, and continue while making a stop at a car wash. Once at the marina, Dial is already there, having figured out their path. Glen smashes through the gate, turns the truck around and backs Willy into the water.

Willy is finally released but does not immediately move, seemingly having been on dry land for too long. Wade and the confederates attempt to interfere, but the group holds them off long enough for Willy to swim away. With Jesse's encouragement, Willy finally begins to swim. Before he can make it, however, two of Dial's whaling ships seal off the marina. Jesse runs towards the breakwater, calling for Willy to follow him, and drawing him away from the nets. Jesse goes to the edge and signals to Willy that if he makes the jump, he'll be free. Jesse says a tearful goodbye, but pulls himself together and goes back to the top. He recites a Haida prayer Randolph had taught him through the story of Natselane, before giving Willy the signal. Willy finally makes the jump over the breakwater and lands in the ocean on the other side, free to return to his family, which a dismayed Dial and Wade can only watch. Jesse thanks Glen and Annie as Willy calls out to Jesse in the distance.

Cast

- Jason James Richter as Jesse, a 12-year old orphan

- Lori Petty as Rae Lindley, Northwest Adventure Park trainer and Willy's veterinarian

- Jayne Atkinson as Annie Greenwood, a teacher, Jesse's foster mother, and Glen's wife

- August Schellenberg as Randolph Johnson, Willy's Haida caregiver

- Michael Madsen as Glen Greenwood, Greenwood Auto Repairs founder and owner, Jesse's foster dad, and Annie's husband

- Michael Ironside as Dial, Northwest Adventure Park owner

- Richard Riehle as Wade, Dial's assistant and Northwest Adventure Park general manager

- Mykelti Williamson as Dwight Mercer, Jesse's social worker

- Michael Bacall as Perry, a runaway orphan and Jesse's friend

- Danielle Harris as Gwenie, a runaway orphan

- Keiko as Willy, a captive 12-year old orca who Jesse befriends

Then-Astoria mayor Willis Van Dusen made a cameo appearance as a fish vendor. Jim Michaels was the announcer for the Northwest Adventure Park's aquatic theater.

Production

Most close-up shots involving limited movement by Willy, such as when Willy is in the trailer and the sequences involving Willy swimming in the open water, make use of an animatronic stand-in. Walt Conti, who supervised the effects for the orcas, estimated that half of the shots of the orca used animatronic stand-ins. Conti stated that the smaller movements of a real orca actually made things difficult in some ways for him and his crew; they had to concentrate on smaller nuances in order to make the character seem alive.[2] The most extensive use of CGI in the film is the climax, filmed at the Hammond Marina in Warrenton, Oregon, where Willy jumps over Jesse and into the wild. All stunts with the orca were performed by the young orca trainer Justin Sherbert (known additionally by his stage name, Justin Sherman). Principal photography took place from May 18 to August 17, 1992.

Release

Box office performance

The film was released alongside Hocus Pocus on July 16, 1993, and grossed $7,868,829 domestically in its opening weekend.[1] It went on to make $76 million in its foreign release and $11,181 from the 2021 re-release in some domestic markets, bringing the film's gross to $153,709,806.[1] Upon its initial release, Free Willy ranked number 5 behind the latter film, Jurassic Park, In the Line of Fire and The Firm at the box office before moving to number 4 by the following weekend and it stayed there for two more weeks. Afterward, its rank in the box office began to gradually decline, with the exception of a three-day weekend (September 3 to 6), in which gross revenue increased by 33.6%.[1]

Critical response

The film has received positive reviews from critics. The Rotten Tomatoes website reported that 71% of critics have given the film a fresh rating based on 31 reviews, with an average rating of 5.6/10.[3] The site's critics consensus reads, "Free Willy tugs at the heartstrings skillfully enough to leap above the rising tide of sentimentality that threatens to drown its formulaic family-friendly story."[3] The film on Metacritic has a weighted average score of 79 out of 100, indicating "generally favorable reviews" from 14 reviews.[4] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on an A+ to F scale.[5]

Accolades

| Date | Award | Category | Recipient(s) and Nominee(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15th Youth in Film Awards | February 5, 1994 | Best Youth Actor Leading Role in a Motion Picture: Drama | Jason James Richter | Won1 | [6] |

| Outstanding Family Motion Picture: Drama | Free Willy | Won | |||

| 1994 Kids' Choice Awards | May 7, 1994 | Favorite Film | Free Willy | Nominated | |

| Favorite Movie Actress | Lori Petty | Nominated | |||

| 1994 MTV Movie Awards | June 4, 1994 | Breakthrough Performance | Jason James Richter | Nominated | |

| Best Kiss | Jason James Richter and Willy | Nominated | |||

| Best Song From a Movie | "Will You Be There" by Michael Jackson | Won | |||

| BMI Film & TV Awards | 1994 | BMI Film Music | Basil Poledouris | Won | |

| Environmental Media Awards | 1994 | Feature Film | Free Willy | Won | |

| Genesis Awards | 1994 | Feature Film | Free Willy | Won | |

| Golden Screen, Germany | 1994 | Golden Screen | Free Willy | Won | |

Notes:

| |||||

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2006: AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – Nominated[7]

Home Video

Free Willy sold almost 9 million units on videocassette.[8] The VHS also had a music video of the Michael Jackson song, I Will Be There.

Soundtrack

| Free Willy: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Various artists | |

| Released | 1993 |

| Length | 59:26 |

| Label | |

| Producer | Joel Sill Gary LeMel Jerry Greenberg |

| Singles from Free Willy: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack | |

| |

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

The Free Willy movie soundtrack was released on July 13, 1993, on CD and audio cassette by MJJ Music in association with the Epic Records sub-label Epic Soundtrax.[10] It contained all the songs that were featured in the movie. Michael Jackson wrote, produced and performed "Will You Be There", originally taken from his 1991 album Dangerous, which can be heard during the end credits. The single version, under the title "Will You Be There (Reprise)", is also included. The song went on to become a top 10 hit in the Billboard Hot 100 charts and was certified platinum as well as winning the 1994 MTV Movie Award for Best Song from a Movie. A remix of SWV's 1992 song "Right Here", which contained a sample of Jackson's "Human Nature", became the group's highest charted single to date and the second biggest hit off the soundtrack when it also landed in the Hot 100 chart at No. 2. New Kids on the Block recorded their first song since they briefly changed their name to NKOTB.[11]

Track listing

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Artist | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Will You Be There (Theme from Free Willy)" | Michael Jackson | Michael Jackson | 5:53 |

| 2. | "Keep on Smilin'" |

| NKOTB | 4:36 |

| 3. | "Didn't Mean to Hurt You" | 3T | 5:47 | |

| 4. | "Right Here" (Human Nature Remix) | SWV | 3:50 | |

| 5. | "How Can You Leave Me Now" | Paul Frazier | Funky Poets | 5:43 |

| 6. | "Main Title" | Basil Poledouris | 5:07 | |

| 7. | "Connection" | Basil Poledouris | 1:44 | |

| 8. | "The Gifts" | Basil Poledouris | 5:19 | |

| 9. | "Friends Montage" | Basil Poledouris | 3:40 | |

| 10. | "Auditon" | Basil Poledouris | 2:04 | |

| 11. | "Farewell Suite

| Basil Poledouris | 12:01 | |

| 12. | "Will You Be There" (Reprise) | Michael Jackson | Michael Jackson | 3:42 |

| Total length: | 59:26 | |||

Keiko

The aquatic star of the film was an orca named Keiko. The huge national and international success of this film inspired a letter writing campaign to get Keiko released from his captivity as an attraction in the amusement park Reino Aventura in Mexico City; this movement was called "Free Keiko". Warner Bros. was so grateful for the whale, and so moved by the fan's ambition, they contributed to rehabilitate and (if possible) free Keiko. He was moved to The Oregon Coast Aquarium in Oregon by flying in a UPS C-130 cargo plane. In Oregon, he was returned to health with the hopes of being able to return to the wild.[12] In 1998, Keiko was moved to Iceland via a US Air Force C-17 to learn to live in the wild. After working with handlers, he was released from a sea pen in the summer of 2002 and swam to Norway following a pod of wild orcas.[13]

His subsequent return to humans for food and for company, and his inability to integrate with a pod of orcas confirms that the project had failed according to a scientific study published in the journal Marine Mammal Science (July 2009).[14][13] Keiko eventually died of pneumonia in a Norwegian bay on December 12, 2003.

A decade later in 2013, a New York Times video reviewed Keiko's release into the wild.[15] Reasons cited for Keiko's failure to adapt include his early age at capture, the long history of captivity, prolonged lack of contact with other orcas, and strong bonds with humans.[16]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d "Free Willy". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ Rickitt, Richard (2006). Designing Movie Creatures and Characters: Behind the Scenes With the Movie Masters. Focal Press. pp. 161–65. ISBN 978-0-240-80846-8.

- ^ a b "Free Willy (1993)". Rotten Tomatoes. Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- ^ "Free Willy Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ "Home". CinemaScore. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ "15th Annual Youth In Film Awards". YoungArtistAwards.org. Archived from the original on April 3, 2011. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers Nominees" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ "WB pushes 'Willy 2' vid". Variety. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ "Free Willy - Original Soundtrack - Songs, Reviews, Credits - AllMusic". AllMusic. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ Variety Staff (June 10, 1993). "'Willy' music launches MJJ/Epic". Variety. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Young, Sage. "What The Whale From 'Free Willy' Taught Us About Orcas, Long Before 'Blackfish' Hit Theaters". Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ Kurth, Linda Moore (September 11, 2017). Keiko's Story: A Killer Whale Goes Home. Millbrook Press. ISBN 9780761315001. Archived from the original on December 19, 2020. Retrieved September 11, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "BBC - Earth News - Killer whales: What to do with captive orcas?". news.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on August 16, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ Simon, M. (2009). "From captivity to the wild and back: An attempt to release Keiko the killer whale". Marine Mammal Science. 25 (3): 693–705. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2009.00287.x. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved July 6, 2019.

- ^ Winerip, Michael (September 16, 2013). "Retro Report: The Whale Who Would Not Be Freed" (video (11:43)). New York Times. Archived from the original on June 11, 2015. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ "From captivity to the wild and back: An attempt to release Keiko the killer whale" (PDF). Orcanetwork.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 4, 2016. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

External links

- 1993 films

- 1993 drama films

- 1990s children's films

- 1990s adventure films

- American drama films

- American adventure films

- American children's drama films

- American children's adventure films

- 1990s English-language films

- Fictional orcas

- Films adapted into television shows

- Films directed by Simon Wincer

- Films produced by Lauren Shuler Donner

- Films scored by Basil Poledouris

- Films shot in Oregon

- Films set in Oregon

- Films shot in California

- Films shot in Los Angeles County, California

- Films shot in Astoria, Oregon

- Films set in Astoria, Oregon

- Films shot in Portland, Oregon

- Films set in Portland, Oregon

- Films shot in Washington (state)

- Films set in Washington (state)

- Films set in the United States

- Films shot in the United States

- Films shot in Mexico

- Films with underwater settings

- Films set in amusement parks

- Films about dolphins

- Films about whales

- Films about orphans

- Films about juvenile delinquency

- Films about children

- Films about Native Americans

- Films about animal rights

- Films about families

- Films about friendship

- Films about adoption

- Films about animal cruelty

- Films about runaways

- Puppet films

- Regency Enterprises films

- StudioCanal films

- Warner Bros. films

- Free Willy (franchise)

- 1990s American films