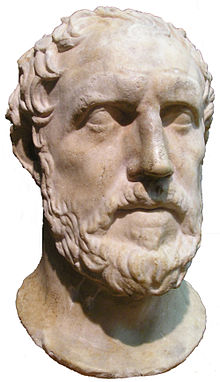

Thucydides

- For the homonymous Athenian politician, see Thucydides (politician).

Thucydides (circa 460 BC – c. 400 BC), Greek Θουκυδίδης, Thoukudídēs) was an ancient Greek historian, and the author of the History of the Peloponnesian War, which recounts the 5th century BC war between Sparta and Athens to the year 411 BC. This is widely considered the first work of scientific history, describing the human world as produced by men acting from ordinary motives, without the intervention of the gods.

Life

Almost everything we know about the life of Thucydides comes from his own History of the Peloponnesian War. Thucydides' father was Olorus,(refactored from Thucy_4.104.4) a name connected with Thrace and Thracian royalty.(refactored from Herod_6.39.1) His daughter was believed to have been buried in the same area as Creon, a Thracian Prince or King. Another Thucydides was said to have lived before the one in question and was also linked with Thrace. He was a man of influence and wealth. He owned gold mines at Scapte Hyle, a district of Thrace on the Thracian coast opposite the island of Thasos.(refactored from Herod_6.46.1;Thuc_4.105.1;Plut_Cim_4.1)

Thucydides, born in Alimos, was connected through family to the Athenian statesman and general Miltiades, and his son Cimon, leaders of the old aristocracy supplanted by the Radical Democrats. Thucydides lived between his two homes, in Athens and in Thrace. His family's connections brought him into contact with the very men who were shaping the history he wrote about.

He was probably in his twenties when the Peloponnesian War began, in 431 BC. He contracted the plague that ravaged Athens(refactored from Thuc_2.48.1-3) between 430 and 427 BC, killing Pericles, in 429 BC, along with thousands of other Athenians.(refactored from Thuc_3.87.1-3)

In 424 BC he was appointed strategos (general), and given command of a squadron of seven ships, stationed at Thasos, probably because of his connections to the area. During the winter of 424-423 BC, the Spartan general Brasidas attacked Amphipolis, a half-day's sail west from Thasos on the Thracian coast. Eucles, the Athenian commander at Amphipolis, sent to Thucydides for help.(refactored from Thuc_4.104.1)

Brasidas, aware of Thucydides' presence on Thasos and his influence with the people of Amphipolis and afraid of help arriving by sea, acted quickly to offer moderate terms to the Amphipolitans for their surrender, which they accepted. Thus when Thucydides arrived, Amphipolis was already under Spartan control(refactored from Thuc_4.105.1-106.3) (see Battle of Amphipolis).

Amphipolis was of considerable strategic importance, and news of its fall caused great consternation in Athens.(refactored from Thuc_4.108.1-7) Because of his failure to save Amphipolis, Thucydides says:

- It was also my fate to be an exile from my country for twenty years after my command at Amphipolis; and being present with both parties, and more especially with the Peloponnesians by reason of my exile, I had leisure to observe affairs somewhat particularly.(refactored from Thuc_5.26.5)

Using his status as an exile from Athens to travel freely among the Peloponnesian allies, he was able to view the war from the perspective of both sides. During this time, he conducted important research for his history.

The remaining evidence for Thucydides' life comes from less-reliable later ancient sources. According to Pausanias, someone named Oenobius was able to get a law passed allowing Thucydides to return to Athens, presumably sometime shortly after Athens' surrender and the end of the war in 404 BC.(refactored from Paus_1.23.9) Pausanias goes on to say that Thucydides was murdered on his way back to Athens. Many doubt this account, seeing evidence to suggest he lived as late as 397 BC. Plutarch claims that his remains were returned to Athens and placed in Cimon's family vault.(refactored from Plut_Cim_4.1)

The abrupt end of his narrative, which breaks off in the middle of the year 411 BC, has traditionally been interpreted as indicating that he died while writing the book, though other explanations have been put forward.

Education

Although there is no certain evidence to prove it, the rhetorical character of his narrative suggests that Thucydides was at least familiar with the teachings of the Sophists. These men were traveling lecturers, who frequented Athens and other Greek cities.

It has also been asserted that Thucydides' strict focus on cause and effect, his fastidious devotion to observable phenomena to the exclusion of other factors and his austere prose style were influenced by the methods and thinking of early medical writers such as Hippocrates of Kos. Some have gone so far as to assert that Thucydides had some medical training.

Both of these theories are inferences from the perceived character of Thucydides' History. While neither can be categorically rejected, there is no firm evidence for either.

Character

Inferences about Thucydides' character can only be drawn (with due caution) from his book. Occasionally throughout "The History of the Peloponnesian War" his sardonic sense of humor is hinted at, such as during the Athenian plague (Book II), when he remarks that some old Athenians seemed to remember a rhyme that said with the Dorian War would come a "great death." Some claimed the rhyme was actually about a "great dearth" (limos), and was only remembered as "death" (loimos) due to the current plague. Thucydides then remarks that, should another Dorian War come, this time attended with a great dearth, the rhyme will be remembered as "dearth," and any mention of "death" forgotten.

Thucydides admired Pericles and approved of his power over the people, though he detested the more pandering demagogues who followed him. Thucydides did not approve of the radical democracy Pericles ushered in but thought that it was acceptable when in the hands of a good leader. He was also strategos under Pericles, which has already been mentioned and therefore presumably would have had an insight into his strategy, which he approved of. It should also be worth remembering that Thucydides problems were connected with Cleon, who prosecuted him over his failure at Thasos. Therefore, he personally would make a distinction between the Athens during Pericles and the Athen's after his death.

Although Thucydides has sometimes been misrepresented as a cold chronicler of events, strong passions occasionally break through in his writing, for example in his scathing appraisals of demagogues such as Cleon and Hyperbolus. And Thucydides was clearly moved by the suffering inherent in war, and concerned about the excesses to which human nature is apt to resort in such circumstances. For example, this is evident from his analysis of the atrocities committed during civil conflict on Corcyra in Book 3, Chapters 82-83, which includes the memorable phrase "War is a violent teacher".

The History of the Peloponnesian War

Thucydides wrote only one book; its modern title is the History of the Peloponnesian War. All his legacy to history and historiography is contained in this one dense history of the twenty-seven year war between Athens and its allies and Sparta and its allies. The history breaks off near the end of the 21st year.

Thucydides is generally regarded as one of the first true historians. Like his predecessor Herodotus (often called "the father of history"), Thucydides placed a high-value on autopsy, or eye-witness testimony to events, and writes about many episodes in which he himself probably took part. He also assiduously consulted written documents and interviewed participants in the events that he records. Unlike Herodotus, he did not recognize divine interventions in human affairs. Certainly he held unconscious biases — for example, to modern eyes he seems to underestimate the importance of Persian intervention — but Thucydides was the first historian who attempted something like modern historical objectivity.

One major difference between Thucydides' history and modern historical writing is that Thucydides' history includes lengthy speeches which, as he himself states, were as best as could be remembered of what was said (or, perhaps, what he thought ought to have been said). These speeches are composed in a literary manner. For example, Pericles' funeral speech, which includes an impassioned moral defence of democracy, heaping honour on the dead:

The whole earth is the sepulchre of famous men; they are honoured not only by columns and inscriptions in their own land, but in foreign nations on memorials graven not on stone but in the hearts and minds of men.

Although attributed to Pericles, this passage appears to have been written by Thucydides for deliberate contrast with the account of the plague in Athens which immediately follows it:

Though many lay unburied, birds and beasts would not touch them, or died after tasting them. ... The bodies of dying men lay one upon another, and half-dead creatures reeled about the streets and gathered round all the fountains in their longing for water. The sacred places also in which they had quartered themselves were full of corpses of persons that had died there, just as they were; for as the disaster passed all bounds, men, not knowing what was to become of them, became utterly careless of everything, whether sacred or profane. All the burial rites before in use were entirely upset, and they buried the bodies as best they could. Many from want of the proper appliances, through so many of their friends having died already, had recourse to the most shameless sepultures: sometimes getting the start of those who had raised a pile, they threw their own dead body upon the stranger's pyre and ignited it; sometimes they tossed the corpse which they were carrying on the top of another that was burning, and so went off.

Classical scholar Jacqueline de Romilly first pointed out, just after the second world war, that one of Thucydides' central themes was the ethic of Athenian imperialism. Her analysis put his history in the context of Greek thought on the topic of international politics. Since her fundamental study, many scholars have studied the theme of power politics, i.e. realpolitik, in Thucydides' history.

On the other hand, some authors, including Richard Ned Lebow, reject the common perception of Thucydides as a historian of naked real-politik. They argue that actors on the world stage who had read his work would all have been put on notice that someone would be scrutinizing their actions with a reporter's dispassion, rather than the mythmaker's and poet's compassion and thus consciously or unconsciously participating in the writing of it. His Melian dialogue is a lesson to reporters and to those who believe one's leaders are always acting with perfect integrity on the world stage. It can also be interpreted as evidence of the moral decay of Athens from the shining city on the hill Pericles described in the Funeral Oration to a power-mad tyrant over other cities.

Thucydides does not take the time to discuss the arts, literature or society in which the book is set and in which Thucydides himself grew up. Thucydides was writing about an event and not a period and as such took lengths not to discuss anything which he considered unrelated.

Leo Strauss, in his classic study The City and Man (see esp. pp. 230-31) argued that Thucydides had a deeply ambivalent understanding of Athenian democracy: on the one hand, "his wisdom was made possible" by the Periclean democracy, on account of its liberation of individual daring and enterprise and questioning; but this same liberation spurred the immoderation of limitless political ambition and thus imperialism, and eventually civic strife. This is the essence of the tragedy of Athens or of democracy -- this is the tragic wisdom that Thucydides conveys, which he learned in a sense from Athenian democracy. More conventional scholars view him as recognizing and teaching the lesson that democracies do need leadership -- and that leadership can be dangerous to democracy.(refactored from Russett)

In 1991, the BBC broadcast a new version of John Barton's 'The War that Never Ends', which had first been performed on stage in the 1960s. This adapts Thucydides' text, together with short sections from Plato's dialogues. More information about it can be found on the Internet Movie Data Base at http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0103235/.

Quotes

- "But, the bravest are surely those who have the clearest vision of what is before them, glory and danger alike, and yet notwithstanding, go out to meet it."(refactored from Thuc_2.40.3)

- "The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must."(refactored from Thuc_5.89)

- "It is a general rule of human nature that people despise those who treat them well, and look up to those who make no concessions."(refactored from Thuc_3.39.5)

- "War takes away the easy supply of daily wants, and so proves a rough master, that brings most men's characters to a level with their fortunes."(refactored from Thuc_3.82.2)

- "The cause of all these evils was the lust for power arising from greed and ambition; and from these passions proceeded the violence of parties once engaged in contention."(refactored from Thuc_3.82.8)

See also

Superiority lies with he who is reared in the severest school.

Notes

|

Template:Ent Thucydides 4.104.4. Template:Ent Herodotus 6.39.1. Template:Ent Herodotus 6.46.1; Thucydides 4.105.1, Plutarch, Cimon 4.1. Template:Ent Thucydides 2.48.1 – 3. Template:Ent Thucydides 3.87.1 – 3. Template:Ent Thucydides 4.104.1. Template:Ent Thucydides 4.105.1 – 106.3. Template:Ent Thucydides 4.108.1 – 7. |

Template:Ent Thucydides 5.26.5. Template:Ent Pausanias 1.23.9. Template:Ent Plutarch, Cimon 4.1. Template:Ent Russett p.45. Template:Ent Thucydides 2.40.3 Template:Ent Thucydides 5.89 Template:Ent Thucydides 3.39.5 Template:Ent Thucydides 3.82.2 Template:Ent Thucydides 3.82.8 |

References and further reading

Primary sources

- Herodotus, Histories, A. D. Godley (translator), Cambridge: Harvard University Press (1920). ISBN 0-674-99133-8 .

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, Books I-II, (Loeb Classical Library) translated by W. H. S. Jones; Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. (1918). ISBN 0-674-99104-4. .

- Plutarch, Lives, Bernadotte Perrin (translator), Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. London. William Heinemann Ltd. (1914). ISBN 0-674-99053-6 .

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War. London, J. M. Dent; New York, E. P. Dutton (1910). .

Secondary sources

- Connor, W. Robert, Thucydides. Princeton: Princeton University Press (1984). ISBN 0-691-03569-5.

- Dewald, Carolyn. Thucydides' War Narrative: A Structural Study. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 0520241274).

- Forde, Steven, The ambition to rule : Alcibiades and the politics of imperialism in Thucydides. Ithaca : Cornell University Press (1989). ISBN 0-8014-2138-1.

- Hanson, Victor Davis, A War Like No Other: How the Athenians and Spartans Fought the Peloponnesian War. New York: Random House (2005). ISBN 1-4000-6095-8.

- Hornblower, Simon, A Commentary on Thucydides. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon (1991-1996). ISBN 0-19-815099-7 (vol. 1), ISBN 0-19-927625-0 (vol. 2).

- Hornblower, Simon, Thucydides. London: Duckworth (1987). ISBN 0-7156-2156-4.

- Luce, T.J., The Greek Historians. London: Routledge (1997). ISBN 0-415-10593-5.

- Orwin, Clifford, The Humanity of Thucydides. Princeton: Princeton University Press (1994).

- Romilly, Jacqueline de, Thucydides and Athenian Imperialism. Oxford: Basil Blackwell (1963). ISBN 0-88143-072-2.

- Rood, Tim, Thucydides: Narrative and Explanation. Oxford: Oxford University Press (1998). ISBN 0-19-927585-8.

- Russett, Bruce (1993). Grasping the Democratic Peace. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03346-3.

- Strassler, Robert B, ed. The Landmark Thucydides: A Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War. New York: Free Press (1996). ISBN 0-684-82815-4.

- Strauss, Leo, The City and Man Chicago: Rand McNally, 1964.