KV19

| KV19 | |

|---|---|

| Burial site of Mentuherkhepshef | |

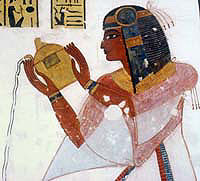

Prince Mentuherkhepshef presents an offering to Banebdjed in KV19. | |

| Coordinates | 25°44′20.2″N 32°36′11.7″E / 25.738944°N 32.603250°E |

| Location | East Valley of the Kings |

| Discovered | 9 October 1817 |

| Excavated by | Giovanni Belzoni (1817) Edward R. Ayrton (1906) |

| Decoration | Book of the Dead (portions) |

← Previous KV18 Next → KV20 | |

Tomb KV19, located in a side branch of Egypt's Valley of the Kings, was intended as the burial place of Prince Ramesses Sethherkhepshef, better known as Pharaoh Ramesses VIII, but was later used for the burial of Prince Mentuherkhepshef instead, the son of Ramesses IX, who predeceased his father. Though incomplete and used "as is," the decoration is considered to be of the highest quality.

Location and layout

[edit]

The tomb is located under the cliffs on the eastern side of the Valley of the Kings, between the tombs of Thutmose IV (KV43) and Hatshepsut (KV20).[1]

The simple layout consists of a single corridor; quarrying had barely progressed into the second corridor when work stopped.[2] At the end of the corridor, an oblong pit was sunk into the floor to receive the burial, which was covered with limestone slabs. The quarrying style and projected layout date it to the Twentieth Dynasty.[1] The location of the tomb and size of the corridor suggest it was initiated for a king. However, traces of an original inscription on the door jambs reveal that the tomb was intended for Ramesses VIII when he was a prince.[2]

Discovery and excavation

[edit]The tomb was rediscovered on 9 October 1817 by Giovanni Battista Belzoni, who briefly described it, making special mention of the decoration:

The painted figures on the walls are so perfect, that they are the best adapted of any I ever saw so give a correct and clear idea of the Egyptian taste.[3]

The tomb was later visited by explorers and researchers including Jean-François Champollion,[4] Karl Richard Lepsius,[5] and Eugène Lefébure[6] as part of their respective archaeological and epigraphical missions.

In 1903 Howard Carter excavated in front of this tomb, discovering KV60.[7]

KV19 was excavated by Edward R. Ayrton in 1906. He notes in his report that the tomb had never been fully cleared, and resolved to end his 1905–1906 fieldwork season with its excavation. By this time only the porch was visible as the rest was covered by debris. The tomb was found to be half filled with large blocks. Ayrton concluded that they could not have been washed in by accident as there was a high drystone wall only 3 feet (0.91 m) from the door. Few portable artefacts were recovered. The finds consisted of ostraca naming Ramesses IV and Ramesses X, faience items inscribed with the name of Ramesses IV from a foundation deposit, and parts of a large stela dedicated by a necropolis workman named Hay. Ayrton theorised, based on the presence of a part of the stela being recovered from a Coptic midden in front of the tomb of Ramesses IV (KV2), that the items from that king's foundation deposit had been moved to KV19 as a result of robber activity. He noted that only wooden items were found during his excavation of Ramesses IV's foundation deposit and that it was clearly originally much larger. The burial pit contained broken pottery vessels and the upper part of a mummy.[1] Earlier visitors had found the tomb to contain intrusive burials of a later, Twenty-second Dynasty date.[8]

Decoration

[edit]The exterior surfaces of the tomb are plastered and undecorated. The outside of the door jambs are plain for most of their height except for roughly cut hieroglyphs outlined in red at the base. Inside, the jambs are completely covered by three columns of black hieroglyphs; below them on each side are a pair of rearing cobras spitting fire. Those on the right side are named as Isis and Nephthys; those on the left are named as Serket and Neith.[1]

The interior decoration is executed on a fine white plaster background. Painted immediately on either side of the entrance are the two halves of a door; the left leaf is covered in the hieratic text of Chapter 139 of the Book of the Dead, while the right has Chapter 123 with two extra lines. The length of the corridor is painted with seven scenes on each side; the ceiling is plain white.[1] The paintings are of the finest Ramesside style. Overall, the decorative scheme is similar to that seen in the tombs of princes in the Valley of the Queens.[2]

Mentuherkhepeshef, with the sidelock of youth on his wig and wearing a fine translucent robe, is depicted making offerings to Osiris, Ptah-Tatenen, Khonsemweset-Neferhotep, Bastet, Imseti, Qebehsenuef, and Amun-Ra on the left wall; on the right he makes offerings to Ptah, Thoth (whose belt buckle bears the prenomen of Ramesses IX), Banebdjedet, Hapi, Duamutef, Meretseger, and Sekhmet.[1][9] As an adult son, Mentuherkhepeshef appears alone before the gods, instead of being escorted by his father.[2]

Graffiti

[edit]Ayrton noted numerous graffiti scratched into the walls.[1] On the right side is a graffito that records the name of a hitherto unknown Scribe in the Place of Truth Ptahemwia. On the left wall are two graffiti: one names the tomb's owner; the other names the Overseer of the Workshop of the Mansion of Gold Ser-[Dje]huty.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Davis, Theodore M.; Maspero, Gaston; Ayrton, Edward; Daressy, George; Jones, E. Harold (1908). The Tomb of Siptah; The Monkey Tomb and the Gold Tomb (PDF). London: Archibald Constable and Co., Ltd. pp. 20–31. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d Reeves, Nicholas; Wilkinson, Richard H. (2010). The Complete Valley of the Kings: Tombs and Treasures of Egypt's Greatest Pharaohs (Paperback reprint ed.). London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. pp. 170–171. ISBN 978-0-500-28403-2.

- ^ Belzoni, Giovanni Battista; Belzoni, Mrs (Sarah) (1820). Narrative of the Operations and Recent Discoveries within the Pyramids, temples, tombs, and excavations, in Egypt and Nubia; and of a journey to the coast of the Red Sea, in search of the ancient Berenice, and of another to the oasis of Jupiter Ammon. London: J. Murray. p. 227.

- ^ Champollion, Jean-François (1844). Monuments de l'Egypte et de la Nubie,...: notices descriptives I (in French). Didot. pp. 463–465.

- ^ Lepsius, Richard (1849). Denkmaeler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien Dritter Band: Theben (in German) (1970 reprint ed.). Osnabrück: Biblio. pp. 220–221.

- ^ Lefébure, Eugène (1889). Les hypogées royaux de Thèbes (Tome Troisième): Notices des hypogées (in French). Paris. pp. 164–167.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Carter, Howard (1903). "Report of Work Done in Upper Egypt (1902–1903)". Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte. 4: 176–177. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ Reeves, C. N. (1990). Valley of the Kings: Decline of a royal necropolis. London: Kegan Paul International. pp. 134–135. ISBN 0-7103-0368-8.

- ^ Porter, Bertha; Moss, Rosalind L. B. (1964). Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs, and Paintings I: The Theban Necropolis, Part II – Royal Tombs and Smaller Cemeteries (PDF) (Second ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 546.

- ^ Peden, Alexander J. (2001). The Graffiti of Pharaonic Egypt: Scope and Roles of Informal Writings (c. 3100–332 B.C.). Leiden: Brill. pp. 206–207. ISBN 978-90-04-12112-6. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

External links

[edit] Media related to KV19 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to KV19 at Wikimedia Commons- Theban Mapping Project: KV19 includes description, images, and plans of the tomb.