Foreign interventions by China

The People's Republic of China has intervened in foreign countries on numerous occasions. Traditionally, official stances by China included a non-intervention approach, though as it became an emerging power, it has utilized intervention tactics.[1]

Characteristics

In order to "maintain order" both domestically and abroad, China enacts both policies of non-interventionism and interventionism.[1] Being the world's second largest aid donor, China uses economic policies to intervene internationally, providing developmental aid to over 100 countries, especially to nations sanctioned by Western governments.[1] Combined, the Export-Import Bank of China and the China Development Bank lend more to developing nations than the World Bank.[2] As China has grown, it has positioned itself to change international networks instead of remaining neutral[3] and to protect its interests abroad, especially in the post–Cold War era.[4] Chinese scholars have increasingly advocated for interventionist policies to protect Chinese interests in a globalized international community.[4]

History

Cold War

Korean War

On 20 August 1950, Premier Zhou Enlai informed the United Nations that "Korea is China's neighbor ... The Chinese people cannot but be concerned about a solution of the Korean question". Thus, through neutral-country diplomats, China warned that in safeguarding Chinese national security, they would intervene against the UN Command in Korea.[5] President Truman interpreted the communication as "a bald attempt to blackmail the UN", and dismissed it.[6]

On 1 October 1950, the day that UN troops crossed the 38th parallel, the Soviet ambassador forwarded a telegram from Joseph Stalin to Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai requesting that China send five to six divisions into Korea, and Kim Il Sung sent frantic appeals to Mao for Chinese military intervention. At the same time, Stalin made it clear that the Soviet Armed Forces themselves would not directly intervene.[7]

In a series of emergency meetings that lasted from 2 to 5 October, Chinese leaders debated whether to send Chinese troops into Korea. There was considerable resistance among many leaders, including senior military leaders, to confronting the U.S. in Korea.[8] Mao strongly supported intervention, and Zhou was one of the few Chinese leaders who firmly supported him. After Lin Biao politely refused Mao's offer to command Chinese forces in Korea (citing his upcoming medical treatment),[9] Mao decided that Peng Dehuai would be the commander of the Chinese forces in Korea after Peng agreed to support Mao's position.[9] Mao then asked Peng to speak in favor of intervention to the rest of the Chinese leaders. After Peng made the case that if U.S. troops conquered Korea and reached the Yalu they might cross it and invade China, the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party agreed to intervene in Korea.[10] On 4 August 1950, with a planned invasion of Taiwan aborted due to the heavy U.S. naval presence, Mao reported to the Politburo that he would intervene in Korea when the People's Liberation Army's (PLA) Taiwan invasion force was reorganized into the PLA North East Frontier Force.[11] On 8 October 1950, Mao redesignated the PLA North East Frontier Force as the Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA).[12]

To enlist Stalin's support, Zhou and a Chinese delegation arrived in Moscow on 10 October, at which point, they flew to Stalin's home at the Black Sea.[13] There, they conferred with the top Soviet leadership, which included Joseph Stalin, as well as Vyacheslav Molotov, Lavrentiy Beria, and Georgi Malenkov. Stalin initially agreed to send military equipment and ammunition, but warned Zhou that the Soviet Air Forces would need two or three months to prepare any operations. In a subsequent meeting, Stalin told Zhou that he would only provide China with equipment on a credit basis, and that the Soviet air force would only operate over Chinese airspace, and only after an undisclosed period of time. Stalin did not agree to send either military equipment or air support until March 1951.[14] Mao did not find Soviet air support especially useful, as the fighting was going to take place on the south side of the Yalu.[15] Soviet shipments of matériel, when they did arrive, were limited to small quantities of trucks, grenades, machine guns, and the like.[16]

Immediately on his return to Beijing on 18 October 1950, Zhou met with Mao, Peng, and Gao Gang, and the group ordered two hundred thousand Chinese troops to enter North Korea, which they did on 25 October.[17] UN aerial reconnaissance had difficulty sighting PVA units in daytime, because their march and bivouac discipline minimized aerial detection.[18] The PVA marched "dark-to-dark" (19:00–03:00), and aerial camouflage (concealing soldiers, pack animals, and equipment) was deployed by 05:30. Meanwhile, daylight advance parties scouted for the next bivouac site. During daylight activity or marching, soldiers were to remain motionless if an aircraft appeared, until it flew away.[18] PVA officers were under orders to shoot security violators. Such battlefield discipline allowed a three-division army to march the 460 km (286 mi) from An-tung, Manchuria, to the combat zone in some 19 days. Another division night-marched a circuitous mountain route, averaging 29 km (18 mi) daily for 18 days.[19]

Meanwhile, on 15 October 1950, President Truman and General MacArthur met at Wake Island in the mid-Pacific Ocean. This meeting was much publicized because of the General's discourteous refusal to meet the President on the continental United States.[20] To President Truman, MacArthur speculated there was little risk of Chinese intervention in Korea,[21] and that the PRC's opportunity for aiding the Korean People's Army had lapsed. He believed the PRC had some 300,000 soldiers in Manchuria, and some 100,000–125,000 soldiers at the Yalu River. He further concluded that, although half of those forces might cross south, "if the Chinese tried to get down to Pyongyang, there would be the greatest slaughter" without air force protection.[22][23]

After secretly crossing the Yalu River on 19 October, the PVA 13th Army Group launched the First Phase Offensive on 25 October, attacking the advancing UN forces near the Sino-Korean border. This military decision made solely by China changed the attitude of the Soviet Union. Twelve days after Chinese troops entered the war, Stalin allowed the Soviet Air Force to provide air cover, and supported more aid to China.[24] After inflicting heavy losses on the ROK Army II Corps at the Battle of Onjong, the first confrontation between the Chinese and U.S. Armed Forces occurred on 1 November 1950. Deep in North Korea, thousands of soldiers from the PVA 39th Army encircled and attacked the U.S. Army 8th Cavalry Regiment with three-prong assaults—from the north, northwest, and west—and overran the defensive position flanks in the Battle of Unsan.[25]

The UN Command, however, were unconvinced that the Chinese had openly intervened, because of the sudden Chinese withdrawal. On 24 November, the Home-by-Christmas Offensive was launched with the U.S. Eighth Army advancing in northwest Korea, while the US X Corps attacked along the Korean east coast. But the PVA were waiting in ambush with their Second Phase Offensive, which they executed at two sectors: in the East at the Chosin Reservoir and in the Western sector at Ch'ongch'on River.[citation needed]

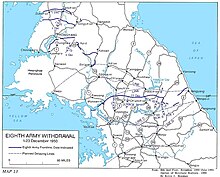

After consulting with Stalin, on 13 November, Mao appointed Zhou Enlai the overall commander and coordinator of the war effort, with Peng as field commander.[17] On 25 November, at the Korean western front, the PVA 13th Army Group attacked and overran the ROK II Corps at the Battle of the Ch'ongch'on River, and then inflicted heavy losses on the US 2nd Infantry Division on the UN forces' right flank.[26] The UN Command retreated; the U.S. Eighth Army's retreat (the longest in US Army history)[27] was made possible because of the Turkish Brigade's successful, but very costly, rear-guard delaying action near Kunuri that slowed the PVA attack for two days (27–29 November). By 30 November, the PVA 13th Army Group managed to expel the U.S. Eighth Army from northwest Korea. Retreating from the north faster than they had counter-invaded, the Eighth Army crossed the 38th parallel border in mid December.[28]

Concurrent with the Battle of the Ch'ongch'on River was the Battle of Chosin Reservoir, which the PVA 9th Army Group initiated on 27 November. Here, the UNC forces fared comparatively better: like the Eighth Army, the surprise attack also forced X Corps to retreat from northeast Korea, but they were, in the process, able to break out from the attempted encirclement by the PVA and execute a successful tactical withdrawal. X Corps managed to establish a defensive perimeter at the port city of Hungnam on 11 December and were able to evacuate by 24 December in order to reinforce the badly depleted U.S. Eighth Army to the south.[29][30] During the Hungnam evacuation, about 193 shiploads of UN Command forces and matériel (approximately 105,000 soldiers, 98,000 civilians, 17,500 vehicles, and 350,000 tons of supplies) were evacuated to Pusan.[31] The SS Meredith Victory was noted for evacuating 14,000 refugees, the largest rescue operation by a single ship, even though it was designed to hold 12 passengers. Before escaping, the UN Command forces razed most of Hungnam city, especially the port facilities.[22][32] On 16 December 1950, President Truman declared a national state of emergency with Presidential Proclamation No. 2914, 3 C.F.R. 99 (1953),[33] which remained in force until 14 September 1978.[a] The next day, 17 December 1950, Kim was deprived of the right of command of the KPA by China.[34]

China justified its entry into the war as a response to "American aggression in the guise of the UN".[11] The Chinese government used the slogan "Resist U.S. Aggression, Aid Korea" to describe its involvement in the Korean War and rally support.[35] The Chinese claimed that U.S. bombers had violated PRC national airspace on three separate occasions and attacked Chinese targets before China intervened.[36][37]

Vietnam War

In 1950, China extended diplomatic recognition to the Viet Minh's Democratic Republic of Vietnam and sent heavy weapons, as well as military advisers led by Luo Guibo, to assist the Viet Minh in its war with the French (1946-1954). The first draft of the 1954 Geneva Accords was negotiated by French prime minister Pierre Mendès France and Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai who, seeing U.S. intervention coming, urged the Viet Minh to accept a partition at the 17th parallel.[38]

China's support for North Vietnam when the U.S. started to intervene included both financial aid and the deployment of hundreds of thousands of military personnel in support roles. In the summer of 1962, Mao Zedong agreed to supply Hanoi with 90,000 rifles and guns free of charge. Starting in 1965, China sent anti-aircraft units and engineering battalions to North Vietnam to repair the damage caused by American Operation Rolling Thunder bombing, man anti-aircraft batteries, rebuild roads and railroads, transport supplies, and perform other engineering works. This freed North Vietnamese Army units for combat in South Vietnam. China sent 320,000 troops and annual arms shipments worth $180 million.[39] The Chinese military claims to have caused 38% of American air losses in the war.[40] China claimed that its military and economic aid to North Vietnam and the Viet Cong totaled $20 billion (approx. $143 billion, adjusted for inflation in 2015) during the Vietnam War.[40] Included in that aid were donations of 5 million tons of food to North Vietnam (equivalent to NV food production in a single year), accounting for 10–15% of the North Vietnamese food supply by the 1970s.[40]

| Year | Guns | Artillery pieces |

Bullets | Artillery shells |

Radio trans- mitters |

Telephones | Tanks | Planes | Auto- mobiles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1964 | 80,500 | 1,205 | 25,240,000 | 335,000 | 426 | 2,941 | 16 | 18 | 25 |

| 1965 | 220,767 | 4,439 | 114,010,000 | 1,800,000 | 2,779 | 9,502 | ? | 2 | 114 |

| 1966 | 141,531 | 3,362 | 178,120,000 | 1,066,000 | 1,568 | 2,235 | ? | ? | 96 |

| 1967 | 146,600 | 3,984 | 147,000,000 | 1,363,000 | 2,464 | 2,289 | 26 | 70 | 435 |

| 1968 | 219,899 | 7,087 | 247,920,000 | 2,082,000 | 1,854 | 3,313 | 18 | ? | 454 |

| 1969 | 139,900 | 3,906 | 119,117,000 | 1,357,000 | 2,210 | 3,453 | ? | ? | 162 |

| 1970 | 101,800 | 2,212 | 29,010,000 | 397,000 | 950 | 1,600 | ? | ? | ? |

| 1971 | 143,100 | 7,898 | 57,190,000 | 1,899,000 | 2,464 | 4,424 | 80 | 4 | 4,011 |

| 1972 | 189,000 | 9,238 | 40,000,000 | 2,210,000 | 4,370 | 5,905 | 220 | 14 | 8,758 |

| 1973 | 233,500 | 9,912 | 40,000,000 | 2,210,000 | 4,335 | 6,447 | 120 | 36 | 1,210 |

| 1974 | 164,500 | 6,406 | 30,000,000 | 1,390,000 | 5,148 | 4,663 | 80 | ? | 506 |

| 1975 | 141,800 | 4,880 | 20,600,000 | 965,000 | 2,240 | 2,150 | ? | 20 | ? |

| Total | 1,922,897 | 64,529 | 1,048,207,000 | 17,074,000 | 30,808 | 48,922 | 560 | 164 | 15,771 |

Sino-Soviet relations soured after the Soviets invaded Czechoslovakia in August 1968. In October, the Chinese demanded North Vietnam cut relations with Moscow, but Hanoi refused.[42] The Chinese began to withdraw in November 1968, in preparation for a clash with the Soviets, which occurred at Zhenbao Island in March 1969.

In January 1974, when the war was about to end, China fought against South Vietnam in the Battle of the Paracel Islands. It was the most famous, and the only, naval battle that China was involved in during the Vietnam War.[43]

The Chinese also began financing the Khmer Rouge as a counterweight to the Vietnamese communists at this time. China "armed and trained" the Khmer Rouge during the Cambodian Civil War and continued to aid Democratic Kampuchea for years afterward.[44] The Khmer Rouge launched ferocious raids into Vietnam in 1975–1978. When Vietnam responded with an invasion that toppled the Khmer Rouge, China launched a brief, punitive invasion of Vietnam in 1979.

Post-Cold War

Asia

China has been the most important trade partner for North Korea and has helped maintain its stability in order to avoid its own domestic threats.[45] When North Korea performs actions that China does not agree with, such as performing tests with its nuclear program, China retaliates and withholds resources from the nation.[45]

Latin America

Into the 21st century, China began to extend its ambitions into Latin America in order to benefit its own growth,[46] with many of the developing countries in the region becoming dependent on a growing China during the 2000s commodities boom.[47] The region eventually relied on funds provided by exports to China. while borrowing from China led to trade deficits and debt among Latin American nations.[47] China has remained close to the governments of Bolivia, Cuba, and Venezuela.[47] Pablo Ava, of the Argentinian Council for International Relations, explained that there were concerns that China would acquire territory like it did in Asia and Africa, where "many countries couldn't pay their credit so China took over not just the administrative control of ports and railways, but the property".[48]

Chinese state-owned Norinco often produces military and riot equipment for oppressive and rogue states, with The New York Times saying that the equipment and systems are "reflective of the hardball tactics that China takes against dissent".[49] This was especially apparent during the crisis in Venezuela, when China supplied riot equipment to Venezuelan authorities combatting the protests in Venezuela.[49] According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, China has also financially assisted Venezuela through its economic crisis so it could domestically benefit from cheap Venezuelan products.[50]

See also

- Foreign interventions by Cuba

- Foreign interventions by the Soviet Union

- Foreign interventions by the United States

- Sino-Third World relations

Notes

- ^ See 50 U.S.C. S 1601: "All powers and authorities possessed by the President, any other officer or employee of the Federal Government, or any executive agency... as a result of the existence of any declaration of national emergency in effect on 14 September 1976 are terminated two years from 14 September 1976."; Jolley v. INS, 441 F.2d 1245, 1255 n.17 (5th Cir. 1971).

References

- ^ a b c Lawson, George; Tardelli, Luca (December 2013). "The past, present, and future of intervention". Review of International Studies. 39 (5): 1233–1253. doi:10.1017/S0260210513000247. S2CID 145394195.

- ^ Chin & Quadir 2012, p. 501.

- ^ Goldstein, Avery (December 2001). "The diplomatic face of China's grand strategy: A rising power's emerging choice". The China Quarterly. 168 (168): 835–864. doi:10.1017/S000944390100050X. S2CID 154598533.

- ^ a b Erickson, Andrew S; Strange, Austin M (January 2014). "Ripples of Change in Chinese Foreign Policy? Evidence from Recent Approaches to Nontraditional Waterborne Security". Asia Policy. 17 (17): 93–126. doi:10.1353/asp.2014.0014.

- ^ Stokesbury 1990, p. 83.

- ^ Offner, Arnold A. (2002). Another Such Victory: President Truman and the Cold War, 1945–1953. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. p. 390. ISBN 978-0804747745.

- ^ Barnouin & Yu 2006, p. 144.

- ^ Halberstam 2007, pp. 355–56.

- ^ a b Halberstam 2007, p. 355.

- ^ Halberstam 2007, p. 359.

- ^ a b Chinese Military Science Academy (September 2000). 抗美援朝战争史 [History of War to Resist America and Aid Korea] (in Chinese). Vol. I. Beijing: Chinese Military Science Academy Publishing House. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-7801373908.

- ^ Chinese Military Science Academy (September 2000). 抗美援朝战争史 [History of War to Resist America and Aid Korea] (in Chinese). Vol. I. Beijing: Chinese Military Science Academy Publishing House. p. 160. ISBN 978-7801373908.

- ^ Halberstam 2007, p. 360.

- ^ Barnouin & Yu 2006, pp. 146, 149.

- ^ Halberstam 2007, p. 361.

- ^ Cumings 2005, p. 266.

- ^ a b Barnouin & Yu 2006, pp. 147–48.

- ^ a b Stokesbury 1990, p. 102.

- ^ Appleman 1998.

- ^ Stokesbury 1990, p. 88.

- ^ Stokesbury 1990, p. 89.

- ^ a b Schnabel, James F (1992) [1972]. United States Army in the Korean War: Policy And Direction: The First Year. United States Army Center of Military History. pp. 155–92, 212, 283–84, 288–89, 304. ISBN 978-0160359552. CMH Pub 20-1-1. Archived from the original on 17 May 2011.

- ^ Donovan, Robert J (1996). Tumultuous Years: The Presidency of Harry S. Truman 1949–1953. University of Missouri Press. p. 285. ISBN 978-0826210852.

- ^ Shen, Zhihua (2010). "China and the Dispatch of the Soviet Air Force: The Formation of the Chinese–Soviet–Korean Alliance in the Early Stage of the Korean War". Journal of Strategic Studies. 33 (2): 211–230. doi:10.1080/01402391003590291. S2CID 154427564.

- ^ Stewart, Richard W (ed.). "The Korean War: The Chinese Intervention". history.army.mil. U.S. Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on 3 December 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ^ Stokesbury 1990, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Cohen, Eliot A.; Gooch, John (2006). Military Misfortunes: The Anatomy of Failure in War. New York: Free Press. pp. 165–95. ISBN 978-0743280822.

- ^ Mossman 1990, p. 160.

- ^ Stokesbury 1990, pp. 104–11.

- ^ Mossman 1990, p. 158.

- ^ Stokesbury 1990, p. 110.

- ^ Doyle, James H; Mayer, Arthur J (April 1979). "December 1950 at Hungnam". U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings. 105 (4): 44–65.

- ^ Espinoza-Castro v. I.N.S., 242 F.3d 1181, 30 (2001), archived from the original.

- ^ Jung Chang and Jon Halliday, MAO: The Unknown Story.

- ^ Xu, Youwei; Wang, Y. Yvon (2022). Everyday Lives in China's Cold War Military Industrial Complex: Voices from the Shanghai Small Third Front, 1964-1988. Palgrave MacMillan. pp. 246–247. ISBN 9783030996871.

- ^ Weng, Byron (Autumn 1966). "Communist China's Changing Attitudes Toward the United Nations". International Organization. 20 (4): 677–704. doi:10.1017/S0020818300012935. OCLC 480093623. S2CID 154687870.

- ^ Chinese Military Science Academy (September 2000). 抗美援朝战争史 [History of War to Resist America and Aid Korea] (in Chinese). Vol. I. Beijing: Chinese Military Science Academy Publishing House. pp. 86–89. ISBN 978-7801373908.

- ^ Qiang Zhai, China and the Vietnam Wars, 1950–1975, University of North Carolina Press, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Qiang Zhai (2000), China and the Vietnam Wars, 1950–1975, University of North Carolina Press, p. 135

- ^ a b c Womack, Brantly (2006). China and Vietnam. Cambridge University Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-0521618342.

- ^ Chen Jian, "China's Involvement in the Vietnam War: 1964 to 1969" Archived 2015-07-24 at the Wayback Machine, Cambridge University Press, 2012, p. 379. Citing "Wenhua dageming zhong de jiefangjun" by Li Ke and Hao Shengzhang, p. 416

- ^ Ang, Cheng Guan, Ending the Vietnam War: The Vietnamese Communists' Perspective, p. 27.

- ^ "Paracel Islands | islands, South China Sea | Britannica". 22 September 2023.

- ^ Bezlova, Antoaneta, China haunted by Khmer Rouge links, Asia Times, 21 February 2009.

- ^ a b "Understanding the China-North Korea Relationship". Council on Foreign Relations. 28 March 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ "China built a $50 million space base in Argentina to reach the dark side of the moon, but it's casting a shadow on its neighbors". VICE News. Retrieved 2018-12-03.

- ^ a b c León-Manríquez, José Luis (Fall 2016). "Power Vacuum or Hegemonic Continuity?: The United States, Latin America, and the "Chinese Factor" After the Cold War". World Affairs. 179 (3): 59–81. doi:10.1177/0043820017690946. S2CID 151518405.

- ^ "China Built A Space Base In Argentina To Explore The Dark Side Of The Moon (HBO)", VICE News, 2018-11-30, retrieved 2018-12-03

- ^ a b "The Anti-Protest Gear Used in Venezuela | NYT Investigates". The New York Times. 23 December 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ Rendon, Moises; Baumunk, Sarah (3 April 2018). "When Investment Hurts: Chinese Influence in Venezuela". Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

Works cited

- Appleman, Roy E (1998) [1961]. South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu. United States Army Center of Military History. pp. 3, 15, 381, 545, 771, 719. ISBN 978-0160019180. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- Barnouin, Barbara; Yu, Changgeng (2006). Zhou Enlai: A Political Life. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press. ISBN 978-9629962807.

- Chin, Gregory; Quadir, Fahimul (December 2012). "Introduction: rising states, rising donors and the global aid regime". Cambridge Review of International Affairs. 25 (4): 493–506. doi:10.1080/09557571.2012.744642. S2CID 55463052.

- Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun : A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393327021.

- Halberstam, David (2007). The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 978-1401300524.

- Mossman, Billy C. (1990). Ebb and Flow, November 1950 – July 1951. United States Army in the Korean War. Vol. 5. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army. OCLC 16764325. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- Stokesbury, James L (1990). A Short History of the Korean War. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0688095130.