Oregon Trail

| Oregon National Historic Trail (Oregon Trail) | |

|---|---|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape) | |

| Location | Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho and Oregon, USA |

| Nearest city | Independence, MO |

| Established | 1978 |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

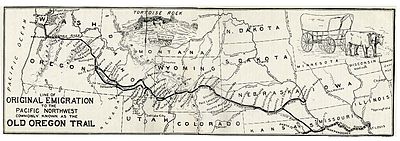

The Oregon Trail was one of the main overland migration routes on which pioneers traveled across the North American continent in wagons in order to settle new parts of the United States of America during the 19th century. The Oregon Trail helped the United States implement its cultural goal of Manifest Destiny, that is, to expand the nation from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. The Oregon Trail spanned over half the continent as the wagon trail proceeded 2,170 miles (3,500 kilometers) west through territories and land later to become six U.S. states (Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, and Oregon). Between 1841 and 1869, the Oregon Trail was used by settlers migrating to the Pacific Northwest of what is now the United States. Once the first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, the use of this trail by long distance travelers diminished as the railroad slowly replaced it.

==History==poop poop poop poop poop

Astorians

The first land route across what is now the United States that was well-mapped was that taken by Lewis and Clark from 1804 to 1805. They believed they had found a practical route to the west coast. However, the pass through the Rocky Mountains they took, Lolo Pass, turned out to be too difficult for wagons to pass. In 1810, John Jacob Astor outfitted an expedition (known popularly as the Astor Expedition or Astorians) to find an overland supply route for establishing a fur trading post at the mouth of the Columbia River at Fort Astoria. Most of Astor's partners and all of his staff were former employees of the Northwest Company, known as Nor'Westers.

Fearing attack by Blackfeet, the expedition veered south of the Lewis and Clark route in what is now South Dakota and in the process passed through what is now Wyoming and then down the Snake River to the Columbia River.

Members of the party, including Robert Stuart, one of the Nor'wester partners, returned back east after the American Fur Company staff there sold the fort to British Northwest Company staff, who took over the outpost in the War of 1812 via the Snake River. The party stumbled upon South Pass: a wide, low pass through the Rockies in Wyoming. The party continued via the Platte River. This turned out to be a practical wagon route, and Stuart's journals were a meticulous account of it.[1]

Fort Astoria was returned to United States control at the end of the war. However, the British Hudson's Bay Company came to control the fur trade in the region, especially after its merger with the North West Company in 1821.

Great American Desert

Westward expansion did not begin immediately, however. Reports from expeditions in 1806 by Lieutenant Zebulon Pike and in 1819 by Major Stephen Long described the Great Plains as "unfit for human habitation" and "The Great American Desert". These descriptions were mainly based on the relative lack of timber and surface water. The images of sandy wastelands conjured up by terms like "desert" were tempered by the many reports of vast herds of bison. It was not until later that the Ogallala Aquifer would be discovered and used for irrigation, and railroads would allow farm products to be transported to distant markets and lumber imported. In the meantime, the Great Plains remained unattractive for general settlement, especially when compared to the fertile lands, big rivers, and seaports of Oregon.

The route of the Oregon Trail began to be scouted out as early as 1823 by fur traders and explorers. The trail began to be regularly used by fur traders, missionaries, and military expeditions during the 1830s. At the same time, small groups of individuals and the occasional family attempted to follow the trail, and some succeeded in arriving at Fort Vancouver in Washington.

Elm Grove Expedition

On May 16, 1842 the first organized wagon train on the Oregon Trail set out from Elm Grove, Missouri, with more than 100 pioneers (members of the party later disagreed over the size of the party, one stating 160 adults and children were in the party, while another counted only 105). Despite company policy to discourage U.S. emigration, John McLoughlin, Factor of the Hudson's Bay Company at Fort Vancouver, offered the American settlers food and farming equipment on credit, being unwilling to watch able-bodied people starve. [citation needed]

Free land

The biggest driving force for settlement was the offer of free land.

In 1843 the settlers of the Willamette Valley by a vote of 52 to 50 drafted a constitution that organized the land claim process in the state. Married couples were allowed to claim up to 640 acres (a "section" which is a square mile, or 260 hectares) at no cost and singles could claim 320 acres (130 ha).[1]

In 1848, the United States formally declared what was left of the Oregon Country a U.S. territory, after it effectively partitioned it in 1846. The Donation Land Act of 1850 superseded the earlier laws, but it did recognize the earlier claims. Settlers after 1850 could be granted half a section (320 acres) if married and a quarter section if single. A four-year residence and cultivation was required. In 1854 the land was no longer free (although still cheap—initially $1.25/acre, or $0.51/ha).

Opening of the trail

In what was dubbed "The Great Migration of 1843" or the "Wagon Train of 1843", [2] [3] an estimated 800 immigrants, led by Marcus Whitman, arrived in the Willamette Valley. Hundreds of thousands more followed, especially after gold was discovered in California in 1848. The trail was still in use during the Civil War, but traffic declined after 1869 when the transcontinental railroad was completed. The trail continued to be used into the 1890s, and modern highways eventually paralleled large portions of the trail.

Other migration paths for early settlers prior to the establishment of the transcontinental railroads involved taking passage on a ship rounding the Cape Horn of South America or to the Isthmus (now Panama) between North and South America. There, an arduous mule trek through hazardous swamps and rain forests awaited the traveler. A ship was typically then taken to San Francisco, California.

Routes

The trail is marked by numerous cutoffs and shortcuts from Missouri to Oregon. The basic route follows river valleys. Starting initially in Independence/Kansas City, the trail followed the Santa Fe Trail south of the Wakarusa River. After crossing The Hill at Lawrence, Kansas, it crossed the Kansas River near Topeka, Kansas, and angled to Nebraska paralleling the Little Blue River until reaching the south side of the Platte River. It followed the Platte, North Platte, and Sweetwater Rivers to South Pass in the Rocky Mountains in Wyoming. From South Pass the trail parallels the Snake River to the Columbia River before arriving at Oregon City or taking the Barlow Road to the Willamette Valley and other destinations in what are now the states of Washington and Oregon.

U.S. Highway 26 follows the Oregon Trail for much of its length.

While the first few parties organized and departed from Elm Grove, the Oregon Trail's generally designated starting point was Independence or Westport on the Missouri River. Several towns along the Missouri River had feeder trails and make claims to being the starting point including Weston, Missouri, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, Atchison, Kansas, and St. Joseph, Missouri.

The Oregon Trail's designated termination point was Oregon City, at the time the proposed capital of the Oregon Territory. However, many settlers branched off or stopped short of this goal and settled at convenient or promising locations along the trail. Commerce with pioneers going further west greatly assisted these early settlements in getting established and launched local micro-economies critical to these settlements' prosperity.

At many places along the trail, alternate routes called "cutoffs" were established either to shorten the trail or to get around difficult terrain. The Lander and Sublette cutoffs provided shorter routes through the mountains than the main route, bypassing Fort Bridger. In later years, the Salt Lake cutoff provided a route to Salt Lake City.

Numerous other trails followed the Oregon Trail for part of its length. These include the Mormon Trail from Illinois to Utah, and the California Trail to the gold fields of California.

Remnants of the trail in Idaho, Kansas, Oregon, and Wyoming, have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Landmarks

Many rock formations became famous landmarks that the Oregon Trail pioneers used to navigate as well as leave messages for pioneers following behind them. The first landmarks that the pioneers encountered were in western Nebraska, such as Courthouse and Jail Rocks, Chimney Rock, and Scotts Bluff. In Wyoming, names of pioneers can be seen carved into a landmark bluff called Register Cliff, and in Independence Rock. One Wyoming landmark along the trail, Ayres Natural Bridge, is now a state park of the same name.

Travel equipment

The Oregon Trail was too long and arduous for the standard Conestoga wagons used in the Eastern United States at that time for most freight transport. These big wagons had a reputation for killing their oxen teams approximately two thirds along the trail and leaving their unfortunate owners stranded in desolate, isolated territory. The only solution was to abandon all belongings and traipse onward with the supplies and tools that could be carried or dragged. In one case in 1846 on the California Trail, the Donner Party, en route to California, was stranded in the Sierra Nevada in November and three members resorted to cannibalism to survive.

This led to the rapid development of the prairie schooners. The wagon was approximately half the size of the big Conestogas but was also manufactured in quantity. It was designed for the Oregon Trail's conditions and was a marvel of engineering in its time. The covers of the wagons were treated with linseed oil to keep out the rain. However, the covers eventually leaked anyway.[citation needed]

The recommended amount of food to take for an adult was 150 pounds (70 kg) of flour, 20 pounds (9 kg) of corn meal, 50 pounds (25 kg) of bacon, 40 pounds (20 kg) of sugar, 10 pounds (5 kg) of coffee, 15 pounds (7 kg) of dried fruit, 5 pounds (2 kg) of salt, half a pound (0.25 kg) of saleratus (baking soda), 2 pounds (1 kg) of tea, 5 pounds (2 kg) of rice, and 15 pounds (7 kg) of beans.[citation needed]

One of the important pieces of equipment for the pioneer were the guns they carried. Rifles, shotguns, and pistols provided protection for the travelers and a way to hunt fresh game to help maintain their physical strength and morale. Many formerly settled travelers, however, were unfamiliar with the safe use of such arms, and gun-related accidents were common on the pioneer trail. The common idea that such weapons were necessary protection from "hostile Natives" arose largely from an inflated view of the threat from tribal peoples to those on the trail; actual interactions were almost always peaceful and resulted in trade helpful to both travelers and natives.[citation needed]

Legacy

The western expansion and the Oregon Trail in particular inspired many songs that told of the settlers' experiences. "Uncle Sam's Farm," encouraged east-coast dwellers to "Come right away. Our lands they are broad enough, so don't be alarmed. Uncle Sam is rich enough to give us all a farm." In "Western Country," the singer exhorts that "if I had no horse at all, I'd still be a hauling, far across those Rocky Mountains, goin' away to Oregon."

When purchasing a new vehicle from 1995-1998, Oregonians could purchase special commemorative Oregon Trail license plates for their cars for an added fee. [4]

The story of the Oregon Trail inspired a popular educational computer game of the same name, The Oregon Trail.

See also

- Shawnee Tribal Villages and Places

- Monticello Township, Kansas (1833-2006)

- California Road - Branch to Lawrence, Kansas from Westport, Missouri

- Donner Party timeline (1846-1847)

- Mormon Trail (1846-1857)

- California Trail (1849-1869)

- Kansas Territory (1854-1861)

- The Oregon Trail: Sketches of Prairie and Rocky-Mountain Life (1847) by Francis Parkman

- Okanagan Trail, 1858-

References

- ^ Philip Ashton Rollins, ed., The Discovery of the Oregon Trail: Robert Stuart's Narratives of His Overland Trip Eastward from Astoria in 1812-13, University of Nebraska, 1995, ISBN 0-803-29234-1

External links

- Oregon or the Grave

- Historic Sites on the Oregon Trail

- Oregon Trail History Library

- Oregon Trail: The Trail West

- Oregon National Historic Trail Home Page

- Oregon Trail Map 1843

- Mitchell Map of 1846

- Music of the Oregon Trail

- Photos and History of the Oregon Trail in Central Wyoming

- Oregon Trail history from Oregon Department of Transportation (with maps)