Song of Roland

The Song of Roland (French: La Chanson de Roland) is the oldest major work of French literature. It exists in various different manuscript versions, which testify to its enormous and enduring popularity in the 12th to 14th centuries. The oldest of these versions is the one in the Oxford manuscript, which contains a text of some 4,004 lines (the number varies slightly in different modern editions) and is usually dated to the middle of the twelfth century (between 1140 and 1170). The epic poem is the first and most outstanding example of the chanson de geste, a literary form that flourished between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries and celebrated the legendary deeds of a hero.

Historical background

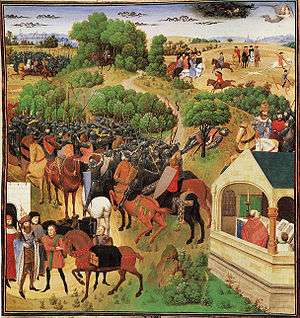

The story told in the poem is based on a relatively minor historical incident, the Battle of Roncevaux Pass on August 15, 778, in which the rearguard of Charlemagne's retreating Franks, escorting a rich collection of booty gathered during a failed campaign in Spain, was attacked by Basques. In this engagement, recorded by historian and biographer Einhard (Eginhard) in his Life of Charlemagne (written around 830), the trapped soldiers were slaughtered to a man; among them was "Hruodland, Prefect of the Marches of Brittany" (Hruodlandus Brittannici limitis praefectus).[1]

The first indication that popular legends were developing about this incident comes in an historical chronicle compiled about 840, which mentions that the names of the Frankish leaders caught in the ambush, including Roland, were "common knowledge" (vulgata sunt).[2] A second indication, potentially much closer to the date of the first written version of the epic, is that (according to somewhat later historical sources) during William the Conqueror's invasion of England in 1066 a "song about Roland" was sung to the Norman troops before they joined battle at Hastings:

- Then a song of Roland was begun, so that the man’s warlike example would arouse the fighters. Calling on God for aid, they joined battle.[3]

- Taillefer, who sang very well, rode on a swift horse before the Duke singing of Charlemagne and Roland and Oliver and the knights who died at Roncevaux.[4]

This cannot be treated as evidence that Taillefer, William's jongleur, was the "author of the Song of Roland", as used to be argued, but it is evidence that he was one of the many poets who shared in the tradition. We cannot even be sure that the "song" sung by Taillefer was the same as, or drew from, the particular "Song of Roland" that we have in the manuscripts. Some traditional relationship is, however, likely, especially as the best manuscript is written in Anglo-Norman French and the Latinized name of its author or transcriber, called "Turoldus," is evidently of Norman origin ("Turold," a variant of Old Norse "Thorvald)."

In view of the long period of oral tradition during which the ambush at Roncevaux was transformed into the Song of Roland, there can be no surprise that even the earliest surviving version of the poem does not represent an accurate account of history. Roland becomes, in the poem, the nephew of Charlemagne, the Basques become Saracens, and Charlemagne, rather than marching north to subdue the Saxons, returns to Spain and avenges the deaths of his knights. The Song of Roland marks a nascent French identity and sense of collective history traced back to the legendary Charlemagne. As remarked above, the dating of the earliest version is uncertain, as is its authorship. Some believe that Turoldus, who is named in the final line, is the author; however, nothing is known about him besides his name. The dialect of the manuscript is Anglo-Norman, which suggests an origin in northern France. However, some critics, notably the influential Joseph Bédier, have held that the real origin of this version of the epic lies much further south.

Perhaps drawing on oral traditions, medieval historians who worked in writing continued to give prominence to the battle of Roncevaux Pass. For example, according to the thirteenth century Arab historian Ibn al-Athir, Charlemagne came to Spain upon the request of the "Governor of Saragossa", Sulayman al-Arabi, to aid him in a revolt against the caliph of Cordoba. Arriving at Saragossa and finding that al-Arabi had had a change of heart, Charlemagne attacked the city and took al-Arabi prisoner. At Roncevaux Pass, al-Arabi's sons collaborated with the Basques to ambush Charlemagne's troops and rescue their father.

Manuscripts

There are nine extant manuscripts of the Song of Roland in Old French. The oldest of these manuscripts is held at the Bodleian Library at Oxford. This copy dates between 1140 and 1170 and was written in Anglo-Norman.[5]

Scholars estimate that the poem was written, more or less, between 1040 and 1115, and most of the alterations were performed by about 1098. Some favor an earlier dating, because it allows one to say that the poem was inspired by the Castilian campaigns of the 1030s, and that the poem went on to be a major influence in the First Crusade. Those who prefer a later dating do so on grounds of the brief references made in the poem to events of the First Crusade. In one section, Palestine is named Outremer, its Crusader name – but is presented as a Muslim land where there are no Christians.

Plot

For seven years, the valiant Christian king Charlemagne has made war against the Saracens in Spain. Only one Muslim stronghold remains, the city of Saragossa, under the rule of King Marsile (or Marsilius) and Queen Bramimonde. Marsile, certain that defeat is inevitable, hatches a plot to rid Spain of Charlemagne. He will promise to be Charlemagne's vassal and a Christian convert in exchange for Charlemagne's departure. But once Charlemagne is back in France, Marsile will renege on his promises. Charlemagne and his vassals, weary of the long war, receive Marsile's messengers and try to choose an envoy to negotiate at Marsile's court on Charlemagne's behalf.

Roland, a courageous knight and Charlemagne's right-hand man, nominates his stepfather, Ganelon. Ganelon is enraged, thinking that Roland has nominated him for this dangerous mission in an attempt to be rid of him for good. Ganelon has long been jealous of Roland, and on his diplomatic mission he plots with the pagans, telling them that they could ambush Charlemagne's rearguard as Charlemagne leaves Spain. Roland will undoubtedly lead the rearguard, and Ganelon promises that with Roland dead Charlemagne will lose the will to fight.

After Ganelon returns with assurances of Marsile's good faith, Roland, as he predicted, ends up leading the rearguard. The twelve peers, Charlemagne's greatest and most beloved vassals, go with him. Among them is Oliver, a wise and prudent man and Roland's best friend. Also in the rearguard is the fiery Archbishop Turin, a clergyman who also is a great warrior. At the pass of Roncevaux, the twenty thousand Christians of the rearguard are ambushed by a vastly superior force, numbering in the hundreds of thousands. Oliver counsels Roland to blow his oliphant horn, to call back Charlemagne's main force, but Roland refuses. The Franks fight valiantly, but in the end they are killed to the man. Roland blows his olifant so that Charlemagne will return and avenge them. His temples burst from the force required, and he dies soon afterward. He dies facing the enemy's land, and his soul is escorted to heaven by saints and angels.

Charlemagne arrives, and he and his men are overwhelmed with grief at the sight of the massacre. He pursues the pagan force, aided by a miracle of God: the sun is held in place in the sky, so that the enemy will not have cover of night. The Franks push the Saracens into the river Ebro, where those who are not chopped to pieces are drowned.

Marsile has escaped and returned to Saragossa, where the remaining Saracens are plunged into despair by their losses. But Baligant, the incredibly powerful emir of Babylon, has arrived to help his vassal. The emir goes to Rencesvals, where the Franks are mourning and burying their dead. There is a terrible battle, climaxing with a one-on-one clash between Baligant and Charlemagne. With a touch of divine aid, Charlemagne slays Baligant, and the Saracens retreat. The Franks take Saragossa, where they destroy all Jewish and Moslem religious items and force the conversion of everyone in the city, with the exception of Queen Bramimonde. Charlemagne wants her to come to Christ of her own accord. With her captive, the Franks return to their capitol, Aix.

Ganelon is put on trial for treason. Pinabel, Ganelon's kinsman and a gifted speaker, nearly sways the jury to let Ganelon go. But Thierry, a brave but physically unimposing knight, says that Ganelon's revenge should not have been taken against a man in Charlemagne's serve: that constitutes treason. To decide the matter, Pinabel and Thierry fight. Though Pinabel is by far the stronger man, God intervenes and Thierry triumphs. The Franks draw and quarter Ganelon (tie each limb to one of four horses running in opposite directions, which tears the victim to pieces). They also hang thirty of his kinsmen.

Charlemagne announces to all that Bramimonde has decided to become a Christian. Her baptism is celebrated, and all seems well.

But that night, the angel Gabriel comes to Charlemagne in a dream, and tells him that he must depart for a new war against the pagans. Weary and weeping, but fully obedient to God, Charlemagne prepares for yet another bloody war.

Form

The poem is written in stanzas of irregular length known as laisses. The lines are of pentameter, and the last stressed syllable of each line in a laisse has the same vowel sound as every other end-syllable in that laisse. The laisse is therefore an assonal, not a rhyming stanza.

On a narrative level, the Song of Roland features extensive use of repetition, parallelism, and thesis-antithesis pairs. Unlike later Renaissance and Romantic literature, the poem focuses on action rather than introspection.

The author gives no explanation for characters' behavior. Characters are stereotypes defined by a few salient traits: for example, Roland is proud and courageous while Ganelon is traitorous and cowardly.

The story moves at a fast pace, occasionally slowing down and recounting the same scene up to three times but focusing on different details or taking a different perspective each time. The effect is similar to a film sequence shot at different angles so that new and more important details come to light with each shot.

Modern readers should bear in mind that the Song of Roland, like Shakespeare's plays, was intended to be performed aloud, not read silently. Traveling jongleurs performed (usually sections of) the Song of Roland to various audiences, perhaps interspersing spoken narration with musical interludes.

Characters

Principal Characters

- Baligant, Emir of Babylon; Marsilion enlists his help against Charlemagne.

- Blancandrin, wise pagan; suggests bribing Charlemagne out of Spain with hostages and gifts, and then suggests dishonoring a promise to allow Marsilion's baptism

- Bramimonde, Queen of Zaragoza; captured and converted by Charlemagne after the city falls

- Charlemagne, Holy Roman Emperor; his forces fight the Saracens in Spain.

- Ganelon, treacherous lord who encourages Marsilion to attack the French

- Marsilius, Saracen king of Spain; Roland wounds him and he dies of his wound later.

- Olivier, Roland's friend; mortally wounded by Marganice. He represents wisdom.

- Roland, the hero of the Song; nephew of Charlemagne; leads the rear guard of the French forces; killed by Marsilion’s troops after a valiant struggle.

- Turpin, Archbishop of Rheims, represents the force of the Church.

Secondary characters

- Aude, the fiancée of Roland and Olivier's sister

- Basan, French baron, murdered while serving as Ambassador of Marsilion.

- Bérengier, one of the twelve paladins killed by Marsilion’s troops; kills Estramarin; killed by Grandoyne.

- Besgun, chief cook of Charlemagne's army; guards Ganelon after Ganelon's treachery is discovered.

- Geboin, guards the French dead; becomes leader of Charlemagne's 2nd column.

- Godefroy, standard bearer of Charlemagne; brother of Thierry, Charlemagne’s defender against Pinabel.

- Grandoyne, fighter on Marsilion’s side; son of the Cappadocian King Capuel; kills Gerin, Gerier, Berenger, Guy St. Antoine, and Duke Astorge; killed by Roland.

- Hamon, joint Commander of Charlemagne's Eighth Division.

- Lorant, French commander of one of the of first divisions against Baligant; killed by Baligant.

- Milon, guards the French dead while Charlemagne pursues the Saracen forces.

- Ogier, a Dane who leads the third column in Charlemagne's army against Baligant's forces.

- Othon, guards the French dead while Charlemagne pursues the Saracen forces.

- Pinabel, fights for Ganelon in the judicial combat.

- Thierry, fights for Charlemagne in the judicial combat.

Adaptations

A Latin poem, Carmen de Prodicione Guenonis, was composed around 1120, and a Latin prose version, Historia Caroli Magni (often known as "The Pseudo-Turpin") even earlier. Around 1170, a version of the French poem was translated into the Middle High German Rolandslied by Konrad der Pfaffe (possible author also of the Kaiserchronik). In his translation Konrad replaces French topics with generically Christian ones. The work was translated into Middle Dutch in the 13th century it was also rendered into Occitan verse in the 14th or 15th century poem of Ronsasvals, which incorporates the later, southern aesthetic into the story. A Norse version of the Song of Roland exists as Karlamagnús saga, and a translation into the artificial literary language of Franco-Venetian is also known; such translations contributed to the awareness of the story in Italy. In 1516 Ludovico Ariosto published his epic Orlando furioso, which deals largely with characters first described in the Song of Roland.

Modern adaptations

The English progressive rock band Van Der Graaf Generator recorded a song, "Roncevaux", that tells the famous story. Norwegian Folk metal band Glittertind and Norwegian polyphonic vocal group Trio Mediæval both recorded versions of "Rolandskvadet," based on part of "The Song of Roland." American power metal band Kamelot have also released a song entitled "Song of Roland".

Fantasy author Judith Tarr has written a novel, Kingdom of the Grail, where she links the story of Roland with the context of Arthurian legend. In particular, Tarr's version of Roland establishes him as a descendant of the wizard Merlin.

Notes

- ^ Einhard, Vita Karoli Magni ch. 9 [1]

- ^ "The Astronomer", Vita Hludovici.

- ^ William of Malmesbury, History of the Kings of England 3.1.

- ^ Wace, Roman de Rou 8013–18.

- ^ Ian, Short (1990). "Introduction". La Chanson de Roland. France: Le Livre de Poche. pp. 5–20.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help)

See also

External links

- The Song of Roland at Project Gutenberg

- The Digby 23 Project at Baylor University

- The Song of Roland

- La Chanson de Roland (Old French)

- Earliest manuscript of the Chanson de Roland, readable online images of the complete original, Bodleian Library MS. Digby 23 (Pt 2) "La Chanson de Roland, in Anglo-Norman, 12th century, ? 2nd quarter".

- Old French Audio clips of a reading of The Song of Roland in Old French

- Timeless Myths: Song of Roland