Dick Tracy (1990 film)

| Dick Tracy | |

|---|---|

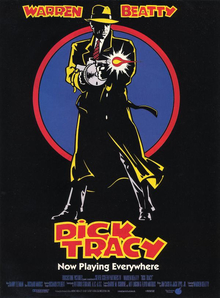

Dick Tracy poster | |

| Directed by | Warren Beatty |

| Written by | Jim Cash Jack Epps Jr. Bo Goldman (uncredited) Chester Gould (comic strip) |

| Produced by | Warren Beatty |

| Starring | Warren Beatty Al Pacino Madonna Glenne Headly Charlie Korsmo Dick Van Dyke Dustin Hoffman |

| Cinematography | Vittorio Storaro |

| Edited by | Richard Marks |

| Music by | Score: Danny Elfman Original songs written by: Stephen Sondheim Original songs performed by: Madonna |

| Distributed by | Touchstone Pictures |

Release dates | |

Running time | 105 min. |

| Country | |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $54 million |

| Box office | $163 million |

Dick Tracy is a 1990 action-adventure film based upon the Dick Tracy comic strip created by Chester Gould. Warren Beatty directed, produced and starred in the leading role. The supporting cast includes Al Pacino, Madonna, Glenne Headly, Charlie Korsmo, Dick Van Dyke and Dustin Hoffman. The story centers around detective Dick Tracy's battle with mobster Alphonse "Big Boy" Caprice (Pacino) and with Tracy's tangled love life with Breathless Mahoney (Madonna) and Tess Trueheart (Headly). In a subplot, Tracy encounters a street orphan going by the simple name of "The Kid", (Korsmo) to whom he becomes a father figure.

Development of the film started in the early 1980s with Tom Mankiewicz assigned to write the script. The project also went through directors Steven Spielberg, John Landis, Walter Hill and Richard Benjamin before the arrival of Beatty. Filming was entirely shot at Universal Studios, whereas Max Allan Collins was involved in heavy controversies with Disney concerning the novelization of the film, and the screenplay. Danny Elfman was hired to compose the film score, and the music in general spawned four separate soundtracks. Dick Tracy was finally released in 1990, and received mixed reviews (mostly positive), being both a success at the box office and the Academy Awards. There, it picked up seven nominations and won three of the categories. A sequel was planned, but a controversy over the film rights ensued between Beatty and Tribune Media Services, and the sequel was never produced.

Plot

While an illegal card game is taking place, a young street urchin witnesses the massacre of a group of mobsters by Flattop, one of the hoods on the payroll of Alphonse "Big Boy" Caprice, whose crime syndicate is aggressively taking over small businesses in the city. Detective Dick Tracy later catches the urchin (who calls himself "Kid") in an act of petty theft. After rescuing him from his ruthless guardian, Tracy temporarily adopts him with the help of his girlfriend, Tess Truehart.

Meanwhile, Big Boy coerces club owner Lips Manlis into signing over the deed to Club Ritz. Big Boy then has Lips killed and steals his girlfriend, the seductive and sultry singer, Breathless Mahoney. After the police find the body, Tracy goes to the club and arrests Big Boy for Lips' murder. Tracy asks Breathless for her testimony, as she is the only witness. Instead of providing testimony she unsuccessfully attempts to seduce Tracy. Big Boy cannot be convicted as there is no evidence, and he is released from jail.

Big Boy's next move is to try to bring the local criminals, including Spud Spaldoni, Pruneface, Ribs Mocca, Mumbles, Itchy, and Numbers, together under his leadership. When Spaldoni refuses, he meets an untimely demise that night. Tracy gets on the case, but without Breathless' testimony, he cannot prove that Big Boy was behind the crimes. He therefore tries one last time to get the testimony from her.

She arrives at Tracy's office wearing a sexy outfit and tells him she will testify if, and only if, he agrees to give in to her sexual advances. He resists, despite his growing attraction to her. Rescued by the Kid, Tracy leads a seemingly unsuccessful raid on Club Ritz, which is only a cover for access to the club. Tracy has one of his men plant a hearing detector in a back room so the police can listen in on Big Boy's criminal activities.

The resultant raids on illegal enterprises all but wipe out Big Boy's criminal empire, but when the crime boss discovers the listening device, he uses it to lure Tracy to him. A man with no face (The "Blank"), however, steps out of the shadows and saves Tracy. Meanwhile, Breathless shows up at Tracy's apartment, once again in an attempt to seduce him. Tracy shows that he can't resist after all when he allows her to kiss him. Tess witnesses them kissing and subsequently leaves town. She eventually has a change of heart, but before she can tell Tracy, she is kidnapped by the Blank. Tracy receives a message to come to the greenhouse where Tess works, but it is another trap. Tracy is drugged by the Blank and framed for the murder of corrupt District Attorney Fletcher.

Big Boy is back in business, but he too has been framed, in this case for Tess' kidnapping. Sprung from jail by his colleagues on New Years Eve, Tracy sets out to rescue his girlfriend. He arrives at a shootout outside Big Boy's club where all of Big Boy's men are gunned down by the police and Tracy himself. Abandoning his crew, Big Boy ties Tess to the mechanism of a drawbridge, but he is confronted by both the Blank and Tracy. Desperate to escape, he shoots the Blank. Enraged, Tracey punches Caprice and sends him falling to his death in the bridge gears. Beneath the faceless figure's mask, Tracy is shocked to find Breathless Mahoney, who kisses him and breathes her last breath. He then frees his girlfriend and his name is cleared from the murder of Fletcher. Later, in the middle of a marriage proposal to Tess, Tracy is interrupted by a robbery in progress, and takes off with the Kid, who now calls himself Dick Tracy Jr.

Cast

- Warren Beatty as Dick Tracy: A square-jawed detective sporting a yellow overcoat and fedora. He finds himself in the path of various mobsters and bogeymen that infest in the city. In addition, he is in line to become the chief of police; a job he refuses as it is a "desk job."

- Al Pacino as Alphonse "Big Boy" Caprice: The main antagonist and the leading crime boss of the city. Although he is involved with various criminal activities, they remain unproven, due to the best efforts of Tracy being overpowered by corrupt District Attorney Fletcher.

- Madonna as Breathless Mahoney / The Blank: An entertainer at Club Ritz who is interested in stealing Tracy from his girlfriend Trueheart. She is also the sole available witness to several of Caprice's crimes.

- Glenne Headly as Tess Trueheart: Dick Tracy's girlfriend. She tries to get him to slow down enjoy life more, and also to marry her.

- Charlie Korsmo as The Kid / Dick Tracy Jr.: A scrawny street orphan who survives by eating out of garbage cans. He falls into the life of both Tracy and Trueheart where he becomes a common ally with Tracy.

- Dick Van Dyke as District Attorney Fletcher: A corrupt city official who had hopes of becoming the Mayor in the recent election. He is unhappy over Tracy arresting criminals without a warrant as he himself works with the various crime bosses.

- Dustin Hoffman as Mumbles: A fast-talking accomplice of Caprice with a voice that no one can understand.

- Paul Sorvino: as Lips Manlis: The original owner of Club Ritz and Caprice's mentor, until Caprice kills him and takes over the club.

- William Forsythe as Flattop: An assassin of Caprice. His most distinguishing feature is his square, flat cranium and matching haircut.

- Ed O'Ross as Itchy: A member of Caprice's gang.

- Mandy Patinkin as 88 keys: A piano player at the Club Ritz who finds himself involved with Caprice's problems.

- R. G. Armstrong as Pruneface: A deformed mobster of Big Boy Caprice.

Production

Sometime in 1980, United Artists was interested in purchasing the rights to the Dick Tracy comic strip. They went as far as hiring Tom Mankiewicz to write a screenplay, though the entire deal fell apart as Chester Gould was asking for too much money and excessive creative control.[1] Producers Art Linson and Floyd Mutrux bought the rights in the same year, and took the property to Paramount Pictures. Steven Spielberg was offered the chance to direct though he declined. Universal Pictures decided to co-distribute the film with Paramount, hiring John Landis to direct. Landis hired Jim Cash and Jack Epps Jr to write the screenplay. His orders to the writers were to do the screenplay for the film centered Big Boy Caprice as the main villain, and in a 1930s atmosphere.[2]

Cash and Epps then read every single comic strip from 1930 to 1957. Epps felt since "there were so many great characters"[3] that he and Cash wished to include as many as they could. Clint Eastwood was offered the leading role of Dick Tracy, but turned it down. In total, the two writers would write two drafts for Landis before the director left after an on-set accident on Twilight Zone: The Movie,[3] in which actor Vic Morrow was killed. Epps was disappointed when Landis left stating that "he would have made it much wilder and zanier."[2]

Max Allan Collins, then writer of the Dick Tracy comic strip, remembers reading one of the drafts. He was unhappy with it, calling it too campy and criticizing the storyline. He was, however, impressed with the rogues gallery and the 1930s setting.[3] Walter Hill came on board as the new director with Joel Silver as producer. Cash and Epps then wrote another draft for the two. Hill took the script, and as Epps states, "[Hill] focused it and threw out a lot of extraneous things and really made it a Tracy draft."[2] While Hill was finishing Streets of Fire, pre-production had progressed as far as set building, and Hill had met with Warren Beatty for the lead role. Hill left the project, which Paramount then began developing as a lower budget version with Richard Benjamin as the new director.[2]

Cash and Epps did two more drafts with Benjamin, though very little detail changed from Hills' draft. Benjamin offered Beatty the leading role but changed his mind when Beatty wanted to be heavily involved during production, since Beatty had been a fan of the Dick Tracy comic strip as a child. Beatty also wanted $5 million and 15% of the box office gross; a deal which Universal Pictures refused to accept. Paramount was not very impressed with the new script, and Benjamin went off to direct City Heat. Paramount and Universal dropped the rights, which were then purchased by Beatty in 1985.[2]

Beatty pitched the project to Disney as the director, feeling no one else in Hollywood could deliver in the same vision he had in mind. Beatty's reputation for directorial profligacy, notably with the critically acclaimed Reds, a $40 million box office failure, did not sit well with Disney.[2] Beatty made a deal with the studio whereby any budget overruns would be deducted from Beatty's fee as producer, director and star. At this point, Collins began lobbying to write the novelization as he had been writing the comic strip for the past thirteen years. Collins' efforts were successful, and was even invited aboard as a consultant and Dick Tracy expert. Meanwhile, Beatty hired collaborator Bo Goldman to rewrite a final shooting script. Collins, who had disapproved an early draft by Cash and Epps, was excited by the news of Goldman being on board as a writer. Collins commented, "The script arrives in the mail, and it's the same lousy Cash and Epps script! Almost nothing had changed!"[4]

Casting

In addition to Clint Eastwood and Warren Beatty's involvement, actors who were reported to be leading candidates for the role of Dick Tracy since the film's development phase in the early 1980s included Harrison Ford, Robert De Niro, Richard Gere, Tom Selleck and Mel Gibson.[4] Although he was eager to do so when first offered, Beatty was hesitant to portray the role, stating "At first, I thought I don't know if I want to play Dick Tracy, because I don't look like him, but then I realized nobody looks like him."[5] Wearing a prosthetic nose and chin as a means to look exactly like the comic strip counterpart was considered, though Beatty dropped the idea as he felt he could not communicate with the audience "wearing outrageous makeup."[4]

Al Pacino was in competition with a long list of A-list actors.[6] Recommended by costume designer Milena Canonero, Beatty hired John Caglione, Jr. and Doug Drexler as the make-up designers. Since the script did not include any physical descriptions of the mobsters, Caglione and Drexler studied Chester Gould's sketches of the comic strip.[7] Beatty was able to assemble a supporting cast filled with famous names and stars, all of whom were friends of Beatty and achieved their respective roles as personal favors.[4]

Beatty was romantically involved with Madonna at the time, as he felt the role of Breathless Mahoney would be perfect for her.[4] Sean Young was originally cast in the role of Tess Trueheart, but was replaced by Glenne Headley after Young claims she refused to sleep with Beatty.[8] Make-up designers John Caglione, Jr. and Doug Drexler jokingly suggested Ronald Reagan for the role of Pruneface, but Beatty opted for Armstrong as he had worked with him on Heaven Can Wait and Reds.[7]

Filming

Warren Beatty decided to make the film using a palette limited to just seven colors. They were primarily red, green, blue and yellow to evoke the film's comic book origins; furthermore each of the colors was to be exactly the same shade. Although Disney resisted the concept, Beatty was able to convince them to go along with the style. Principal photography began at Universal Studios in California on February 2, 1989; it lasted 85 days, spanned 53 interior sets and 25 exterior backlot sets, and often encompassed dozens of takes of every scene.[9] As filming continued, Max Allan Collins continued to work on his novelization, loosely based on an "improved and corrected" script. Disney rejected the manuscript, which Collins claimed it was an act to "fix as many plotholes I could."[9] The author made a deal with Disney that if Beatty liked it, then Disney would have to follow with his changes. Beatty was impressed with Collins' story and Disney decided to accept his ideas for the novelization. Executive producer Barry Osborne began making regular calls to Collins, asking why he had "softened" a scene in which Tess Trueheart's mom tries to convince her daughter to leave Dick Tracy. Collins explained that, as any true fan would know, Mrs Trueheart would more likely defend Tracy because, in the very first episode of the newspaper strip, Tracy had avenged the death of her husband, Tess' father. "When I told Osborne this, there was a long silence at the other end of the phone. They ended up re-shooting the scene, my way."[9] Osborne was impressed with many conclusions Collins made with the scripts problems that some of his dialogue had been used in the finished film.[9]

Music

Warren Beatty was impressed with Danny Elfman's work on Batman, and felt it was natural for him to work on another summer blockbuster. Elfman claimed that "In a completely different way, Dick Tracy has this unique quality that Batman had for me. It gives an incredible sense of non-reality."[10] The composer enlisted the help of Oingo Boingo lead guitarist Steve Bartek to help arrange the compositions for the orchestra. Elfman worked seven days a week and twelve hours a day to complete the score.[10] Beatty enlisted acclaimed songwriter Stephen Sondheim to write several new songs for Madonna to sing. As a result, three soundtrack albums were released to tie in with the film. The first featured Sondheim's songs, while the second showcased Elfman's film score, and finally the most successful was a stand alone album titled I'm Breathless that was filled with Madonna's songs.[11]

Release and controversies

To help market and promote the film, Disney had at one point planned a Broadway stage show at the Videopolis theater in Disneyland. A casting call was written for the roles of both Dick Tracy and Breathless Mahoney.[12] Around the opening release of the film in theaters, Harold Steinberg, a New York real estate developer, filed a lawsuit claiming that Warren Beatty, Walt Disney Studios, and Disney Studios Chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg stole his idea to develop a film from the Dick Tracy comic strip. According to Steinberg, he presented it as a musical to both Beatty and Katzenberg in 1980, but they were not intrigued.[13] This would later be questioned as Beatty did not express interest in the role until 1983, three years after Steinberg's claim.[4]

As a means to promote the film, reruns of The Dick Tracy Show were aired. The cartoon appeared on various independent stations across the United States in June 1990. Asian and Hispanic groups started charging that characters Joe Jitsu (a Japanese buck-toothed character) and Go Go Gomez (a sombrero-wearing Mexican) were offensive stereotypes. Two stations in Los Angeles removed the airings (replaced by episodes of "Underdog") and edited episodes were aired in New York. Henry G. Saperstein, then the chairman of UPA stated "It's just a cartoon, for goodness sake."[14]

Max Allan Collins' novelization caused even more controversy between Disney executives. Since the novelization was scheduled to be published before the film opened, Disney insisted that Collins leave out the identity of the faceless figure to be "The Blank." Collins stated "most people had already figured it out by seeing the credits".[15] The situation was exacerbated when the official Dick Tracy coloring book, also released before the film, featured a panel in which the identity of the Blank was revealed. Due to various disputes over Disney, up to seven printings were published, though in total, almost one million copies were sold.[15]

Box office performance

Dick Tracy was released on June 15, 1990,[16] which meant it had to follow the previous summer's success of Batman. Disney spent a total of $9 million on the film's marketing strategy alone, dealing with its $45 million production budget, coming at a total cost of $54 million.[15] In addition it was the first film released using digital sound.[17] Dick Tracy went on to gross $22.544 million on its opening weekend, garnering 20% of its total box office run. In the final results for its North American run, the film made $103.74 million. Overseas it grossed $59 million. The end result came to a total gross of $162.74 million,[16] declaring itself to be a box office success. Disney, however, was disappointed hoping the film would have the same commercial success as Batman.[15] Dick Tracy was the number nine top grossing film of 1990.[18]

Critical analysis

Based on 38 reviews collected by Rotten Tomatoes, Dick Tracy received an average 66% overall approval rating;[19] the film received a 33% with the six critics in Rotten Tomatoes' "Cream of the Crop."[20] Common reviews highly criticized Warren Beatty for sacrificing the storyline in reserve of the visual design.[19] Ian Freer of Empire was highly impressed with the visuals and the rogues gallery, though ultimately felt the story did not add up. Overall, he gave the film a positive review.[21] Roger Ebert disliked Madonna's performance but praised the film, citing "This is a movie in which every frame contains some kind of artificial effect. An entire world has been built here, away from the daylight and the realism of ordinary city streets."[22] Chris Hicks of The Deseret Morning News felt "[Dick Tracy] is a lot of fun, and fans of the offbeat may embrace it as a unique film amid a sea of movies that seem cloned from each other."[23]

The film, however, also garnered negative reviews. Peter Travers of Rolling Stone commented "For all its superficial pleasures, Dick Tracy ultimately flounders because it provides an audience with nothing to take home and dream about."[24] Desson Thomson of The Washington Post called it "Tinseltown's annual celebration of everything that's wrong with itself: the hype, the agent-negotiated star system; the Hollywood 'fun' assembly-line method of copy-cat mediocrity."[25] Jonathan Rosenbaum of The Chicago Reader liked the visuals, but felt that the film "lacked the [vision] to go with it".[26] He was also of the opinion that the action sequences could have gone in a better direction.[26] Despite his negative feedback with the film's script during development, and his controversial efforts on the novelization with Disney, Max Allan Collins gave the film a positive review. He still had mixed emotion towards the script, but was impressed with Beatty's performance. Stephen Sondheim's music and the ensemble cast of the rogues gallery also helped convinced Collins to review the film positively. In the end, the author noted, "Still, as one critic said, it's like a lovely restored period automobile, but when you raise the hood, there's no engine."[27]

Despite its mixed reviews, Dick Tracy was able to win three Academy Awards:

- Best Art Direction-Set Decoration (Richard Sylbert and Rick Simpson)

- Best Makeup (John Cagilone Jr. and Doug Drexler)

- Best Original Song (Sooner or Later was written by Stephen Sondheim and performed by Madonna)

In addition the film was nominated for another four categories:

- Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Al Pacino)

- Best Cinematography (Vittorio Storaro)

- Best Costume Design (Milena Canonero)

Although it was the first film released with digital sound,[17] it lost the nomination for Best Sound Mixing.[28] Dick Tracy was nominated for Best Motion Picture Comedy/Musical at the Golden Globe Awards. Pacino and Sonheim were nominated for categories as well (with Sondheim being nominated twice).[29] In England, Warren Beatty, Pacino, Madonna and Charlie Korsmo were all given nominations at the Saturn Awards. There the film was also nominated for Best Fantasy Film while winning Best Make-Up.[30] Pacino was nominated for Funniest Supporting Actor in a Motion Picture at the American Comedy Awards,[31] and Storaro was nominated for his work by the American Society of Cinematographers.[32] Danny Elfman and Sondheim were both given Grammy Award nominations.[33] The A.V. Club named Dick Tracy as number five in its top "13 Failed Attempts To Start Film Franchises" list.[34]

Sequel

After the release of the film, producers Art Linson and Floyd Mutrux launched a lawsuit against Warren Beatty, alleging that they were owed profit participation from the film. This lawsuit prevented Beatty from producing another film for two years, but the case was eventually settled.[27] Beatty came up with what he called "a very good idea"[35] for a sequel, but was thwarted by Tribune Media Services, who claimed control over Tracy's character. Beatty then sued the company for $30 million, saying they violated a complex agreement regarding the Tracy rights as far back as 1985. In 2002, according to Beatty's lawsuit, Tribune took back control of Tracy and notified Disney, but not through the process outlined in the agreement. Beatty's attorney quoted, "The Tribune is a big, powerful company and they think they can just run roughshod over people. They picked the wrong guy."[35]

In August 2005, Beatty was allowed to proceed with the lawsuit, having won in the first stage. The Tribune was then denied the motion to dismiss the lawsuit, explaining the case involved issues of contract interpretation and "mixed questions of fact and law"[36] which needed to be sorted through in court. Beatty did state, however, the situation still was "commercially impossible" for him to produce a sequel.[36] By April 2006 the ruling was reported with no forward progress, as Beatty refused to commission a deal with the Tribune feeling he "didn't need consent to reserve the rights."[37] In July 2006, a judge ruled that the case could go to trial; Tribune's request to end the suit in their favor was rejected.[38]

References

- ^ Daniel Dickholtz (1998-12-22). "Steel Dreams: Interview with Tom Mankiewicz". Starlog. pp. 53–57.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e f Hughes, p.52

- ^ a b c David Hughes (2003). Comic Book Movies. Virgin Books. pp. p.51. ISBN 0753507676.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c d e f Hughes, p.53

- ^ "Strip Show The Comic Book Look of Dick Tracy". Entertainment Weekly. 1990-06-15. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ David S. Cohen (2007-06-06). "Al Pacino tackles each role like a novice". Variety. Retrieved 2008-02-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Gregg Kilday (1990-07-06). "Making up is hard to do". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Lew Irwin (2004-07-22). "Young Slams Lecherous Beatty". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d Hughes, p.54-5

- ^ a b "The Elfman Cometh". Entertainment Weekly. 1990-02-23. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Hughes, p.56

- ^ "News & Notes". Entertainment Weekly. 1990-03-16. Retrieved 2007-12-19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "News & Notes: Movie news for the week of June 22, 1990". Entertainment Weekly. 1990-06-22. Retrieved 2007-12-19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Benjamin Svetkey (1990-07-27). "Television News: News & Notes". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2007-12-19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d Hughes, p.57—8

- ^ a b "Dick Tracy (1990)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2007-12-19.

- ^ a b "News & Notes". Entertainment Weekly. 1990-06-15. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The 50 Top Grossing Films of 1990". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2007-12-25.

- ^ a b "Dick Tracy (1990)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ "Dick Tracy (1990): Rotten Tomatoes' Cream of the Crop". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ Ian Freer (2006-03-11). "Dick Tracy review". Empire. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Roger Ebert (1990-06-15). "Dick Tracy review". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Chris Hicks (1990-06-15). "Dick Tracy review". The Deseret Morning News. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Peter Travers (2000-12-18). "Dick Tracy review". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Desson Thomson (1990-06-15). "Dick Tracy review". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Jonathan Rosenbaum. "Dick Tracy review". The Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ a b Hughes, p.59-60

- ^ "The 1991 Academy Awards". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ "The 1991 Golden Globe Awards". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ^ "The 1991 Saturn Awards". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ^ "The 1991 American Comedy Awards". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ^ "The 1991 ASC Awards". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ^ "The 1991 Grammy Awards". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ^ Donna Bowman; Noel Murray; Sean O'Neal; Keith Phipps; Nathan Rabin; Tasha Robinson (2007-04-30). "Inventory: 13 Failed Attempts To Start Film Franchises". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Warren Beatty sues Tribune over Dick Tracy". USA Today. 2005-05-17. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Lew Irwin (2005-08-12). "Beatty Wins First Round in 'Dick Tracy' Battle". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "No Ruling in Beatty Lawsuit over Dick Tracy Rights". Fox News. 2006-04-04. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Stax (2006-07-19). "Beatty Still Following Dick". IGN. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

Further reading

- Mike Bonifer (1990). Dick Tracy: The Making of the Movie. A detailed analysis of the making of the film. Bantam Books. ISBN 0553349007.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Max Allan Collins (1990). Dick Tracy. Novelization of the film. Bantam Books. ISBN 0553285289.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)