Saxophone

| |

| Other names | Sax |

|---|---|

| Classification | |

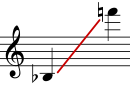

| Playing range | |

|

Written Range:  | |

| Related instruments | |

|

Military band family:

Orchestral family:

Other saxophones: | |

| Musicians | |

The saxophone (commonly referred to simply as sax) is a conical-bored musical instrument considered a member of the woodwind family. Saxophones are usually made of brass and are played with a single-reed mouthpiece similar to the clarinet. The saxophone was invented by Adolphe Sax in 1841, and patented in 1846 in two groups of seven instruments each. Each series consisted of instruments of various sizes in alternating transposition. The series pitched in B♭ and E♭, designed for military bands, has proved extremely popular and most saxophones encountered today are from this series. A few saxophones remain from the less popular orchestral series pitched in C and F.

While proving very popular in its intended niche of military band music, the saxophone is most commonly associated with popular music, big band music, blues, and particularly jazz. There is also a substantial repertoire of concert music in the classical idiom for the members of the saxophone family. Saxophone players are called saxophonists.

History

The saxophone was developed in the 1840s by bob Sax, a Belgian-born instrument-maker,flute player, and clarinetist working in Paris. While still working at his father's instrument shop in Brussels, Sax began developing an instrument which had the projection of a brass instrument with the mobility of a woodwind. Another priority was to create an instrument which, while similar to the clarinet, would overblow at the octave, unlike the clarinet, which rises in pitch by a twelfth when overblown; an instrument which overblew at the octave would have identical fingering for both registers.

Prior to his work on the saxophone, Sax made several improvements to the bass clarinet by improving its keywork and acoustics and extending its lower range. Sax was also a maker of the then-popular ophicleide, a large conical brass instrument in the bass register with keys similar to a woodwind instrument. His experience with these two instruments allowed him to develop the skills and technologies needed to make the first saxophones. Adolph Sax created an instrument with a single reed mouthpiece like a clarinet, conical brass body like an ophicleide, and the acoustic properties of the flute.

Having constructed saxophones in several sizes in the early 1840s, Sax applied for, and received, a 35-year patent for the instrument on June 28 1846.[1] The patent encompassed 14 versions of the fundamental design, split into two categories of seven instruments each and ranging from sopranino to contrabass. In the group Sax envisaged for orchestral work, the instruments transposed at either F or C, while the "military band" group included instruments alternating between E♭ and B♭. The orchestral soprano saxophone was the only instrument to sound at concert pitch. All the instruments were given an initial written range from the B below the treble staff to the F three ledger lines above it, giving each saxophone a range of two and a half octaves.

Sax's patent expired in 1977;[2] thereafter numerous saxophonists and instrument manufacturers implemented their own improvements to the design and keywork. The first substantial modification was by a French manufacturer who extended the bell slightly and added an extra key to extend the range downwards by one semitone to B♭. It is suspected that Sax himself may have attempted this modification. This extension was adopted into almost all modern designs.

Sax's original keywork was very simplistic and made playing some legato passages and wide intervals extremely difficult to finger, so numerous developers added extra keys and alternate fingerings to make chromatic playing less difficult. While the early saxophone had two separate octave vents to assist in the playing of the upper registers just as modern instruments do, players of Sax's original design had to operate these via two separate octave keys operated by the left thumb. A substantial advancement in saxophone keywork was the development of a method by which both tone holes are operated by a single octave key by the left thumb which is now universal on all modern saxophones. One of the most radical, however temporary, revision of saxophone keywork was made in the 1950s by M. Houvenaghel of Paris, who completely redeveloped the mechanics of the system to allow a number of notes (C♯, B, A, G, F and E♭) to be flattened by a semitone simply by lowering the right middle finger. This enables a chromatic scale to be played over two octaves simply by playing the diatonic scale combined with alternately raising and lowering this one digit.[3] However, this keywork never gained much popularity, and is no longer in use.

Description

The saxophone consists of an approximately conical tube of thin metal, most commonly brass, flared at the tip to form a bell. At intervals along the tube are between 20 and 23 tone holes of varying size, including two very small 'speaker' holes to assist the playing of the upper register. These holes are covered by pads, which are capable of pressing the holes to produce an airtight seal; at rest some of the holes stand open and others are closed by pads. The pads can be controlled by a number of keys by the left and right fingers, while the left thumb operates an octave key to open the speaker holes for the upper register. The fingering for the saxophone is a combination of that of the oboe with the Boehm system, and is very similar to the flute or the upper register of the clarinet. On the larger instruments, the leverage required to play the very lowest notes (which are customarily played with the left and right little fingers) is great enough that additional keywork is introduced to enable these to be played with the thumbs.

The simplest design of saxophone is a straight conical tube, and the sopranino and soprano saxophones are usually of this straight design. However, as the lower-pitched instruments would be unacceptably lengthy if straight, the larger instruments usually incorporate a U-bend at or slightly above the third-lowest tone hole. As this would cause the bell of the instrument to point almost directly upwards, the end of the instrument is either beveled or tilted slightly forwards. This U-shape has become an iconic feature of the saxophone family, to the extent that soprano and even sopranino saxes are sometimes made in the curved style even though this is not strictly necessary. By contrast, tenors and even baritones have occasionally been made in the straight style.[4][5] Most commonly, however, the alto and tenor saxophones incorporate a curved 'crook' above the highest tone hole but below the top speaker hole, tilting the mouthpiece through 90 degrees; the baritone, bass and contrabass extend the length of the bore mainly by double-folding this section.

Materials

Nearly all saxophones, past and present, are made from brass. Despite this, they are categorized as woodwind instruments rather than brass due to the fact that the sound waves are produced by an oscillating reed, not the player's lips against a mouthpiece as in a brass instrument, and the fact that different pitches are produced by opening and closing keys. Brass is used to make the body of the instrument; the pad cups; the rods that connect the pads to the keys; the keys themselves and the posts that hold the rods and keys in place. The screw pins that connect the rods to the posts, and the needle springs and leaf springs that cause the keys to return to their rest position after being released, are generally made of blued or stainless steel. Since 1920, nearly all saxophones have 'key touches' (smooth decorative pieces placed where the fingers will touch the instrument) made of either plastic or mother of pearl.

Other materials have been tried with varying degrees of success, as with the 1950s plastic saxophones made by the Grafton company, and the rare wooden saxophones. A few companies, such as Yanagisawa, have made some saxophone models from phosphor bronze[6]. They and some other manufacturers have made saxophone necks or entire instruments from Sterling silver,[7] copper, nickel silver or synthetic materials. Cannonball Saxophones of Salt Lake City, Utah nearly exclusively uses alternative materials in their manufacturing processes including extensive use of black anodized nickel plating.[8] Most uniquely Keilwerth developed a saxophone with a nickel silver body like that of a flute, with a black nickel plating.[9]. Additionally other brands are entering into making saxophones out of nickel silver such as P.Mauriat[10].

After completing the instrument, manufacturers apply a thin coating of clear or colored acrylic lacquer, or silver plate, over the bare brass. The lacquer or plating serves to protect the brass from corrosion, and gives the instrument a pleasing appearance. Several different types and colors of surface finish have been used over the years.[11] It is also possible to plate the instrument with nickel or gold, and a number of gold-plated saxophones have been produced.[11] It is commonly claimed that the type of lacquer or plating, or absence thereof, may enhance an instrument's tone quality; the possible effects of different finishes on tone is a hotly debated topic.[12][13]

Mouthpiece and reed

The saxophone uses a single-reed mouthpiece similar to that of the clarinet, but the saxophone mouthpiece is larger, has a wider inner chamber and lacks the cork-covered tenon of a clarinet mouthpiece because the saxophone neck inserts into the mouthpiece whereas the clarinet mouthpiece piece is inserted into the barrel. The most important difference between a saxophone mouthpiece and a clarinet mouthpiece is that the saxophone mouthpiece should enter the mouth at a much lower or flatter angle than the clarinet. Mouthpieces come in a wide variety of materials, including vulcanized rubber (sometimes called rod rubber or ebonite), plastic, and metals such as bronze or surgical steel. Less common materials that have been used include wood, glass, crystal, porcelain, and even bone. According to Larry Teal, the mouthpiece material has little, if any, effect on the sound, and the physical dimensions give a mouthpiece its tone colour.[14] Mouthpieces with a concave ("excavated") chamber are more true to Adolphe Sex's original design; these provide a softer or less piercing tone, and are favored by some saxophonists, including students of Sigurd Raschèr, for classical playing. Conversely, mouthpieces with a smaller chamber or lower clearance above the reed, called high baffle, produce a brighter sound with maximum projection and are favored by many jazz and funk players. Most skilled saxophonists settle on a mouthpiece somewhere between these extremes regardless of their primary idiom and most that play both jazz and classical music have different equipment for each.

Like clarinets, saxophones use a single reed. Saxophone reeds are proportioned slightly differently to clarinet reeds, being wider for the same length. Each size of saxophone (alto, tenor, etc.) uses a different size of reed. Reeds are commercially available in a vast array of brands, styles, and strengths. Each player experiments with reeds of different strength (hardnesses)and material to find which strength and cut suits his or her mouthpiece, embouchure tendencies and playing style.

Uses of the saxophone

The saxophone was originally patented as a group of 14 instruments in two families. The orchestral family consisted of instruments in the keys of C and F, and the military band family in E♭ and B♭. Each family consisted of sopranino, soprano, alto, tenor, baritone, bass and contrabass instruments, alternating in transposition. While all seven members of the military band family are still relatively common, the orchestral group was less successful; Adolphe Sax's personal rivalry with influential German composer Wilhelm Wieprecht may have been partially responsible for the complete failure of the saxophone in orchestral music. Only the orchestral tenor and soprano saxes, both pitched in C and therefore able to easily play music written for strings or voice, attained any popularity; the tenor was popularized by players such as Rudy Wiedoeft and Frankie Trumbauer, but did not secure a permanent place in either jazz or classical music. In the early 20th century, the orchestral soprano was marketed to those who wished to perform oboe parts in military band, vaudeville arrangements, or church hymnals. None have been produced since the late 1920s. The orchestral alto, produced by the American firm Conn during the period 1928–1929, is now extremely rare; most remaining examples are in the possession of serious instrument collectors. Adolphe Sax made a few F baritone prototypes, but no serious F baritones were manufactured. There are no known remaining specimens of the bass saxophone in C, the first saxophone constructed and exhibited by Sax in the early 1840s, or the sopranino in F, despite Ravel's scoring for the instrument in Bolero. The only known F alto made by Sax himself known to exist is owned by retired Canadian classical saxophonist Paul Brodie.

The saxophone first gained popularity in the niche it was designed for: the military band. Although the instrument was studiously ignored in Germany, French and Belgian military bands took full advantage of the instrument that Sax had designed specifically for them. Most French and Belgian military bands incorporate at least a quartet of saxophones comprising at least the E♭ baritone, B♭ tenor, E♭ alto and B♭ soprano. These four instruments have proved the most popular of all of Sax's creations, with the E♭ contrabass and B♭ bass usually considered impractically large and the E♭ sopranino insufficiently powerful. British military bands tend to include at minimum two saxophonists on the alto and tenor.

The saxophone has more recently found a niche in both concert band and big band music, which often calls for the E♭ baritone, B♭ tenor and E♭ alto. The B♭ soprano is also occasionally utilised, in which case it will normally be played by the first alto saxophonist. The bass saxophone in B♭ is called for in band music (especially music by Percy Grainger) and big band orchestrations, especially music performed by the Stan Kenton "Mellophonium Orchestra". In the 1920s the bass saxophone was used often in classic jazz recordings, since at that time it was easier to record than a tuba or double bass. It is also used in the original score (and movie) of Leonard Bernstein's West Side Story. The saxophone has been more recently introduced into the symphony orchestra, where it has found increased popularity. In one or other size, the instrument has been found a useful accompaniment to genres as wide-ranging as opera, choral music and chamber pieces. Many musical scores include parts for the saxophone, usually assigned to the second or third reed.

Saxophone ensembles

By far the most well known, and iconic, implementation of the saxophone is in modern jazz music, usually in the form of a saxophone quartet or larger ensemble.

The saxophone quartet is usually made up of one B♭ soprano, one E♭ alto, one B♭ tenor and one E♭ baritone. On occasion, the soprano is replaced with a second alto sax; a few professional saxophone quartets have featured non-standard instrumentation, such as James Fei's Alto Quartet[15] (four altos) and Hamiet Bluiett's Bluiett Baritone Nation (four baritones).

There is a repertoire of classical compositions and arrangements for the soprano-alto-tenor-baritone instrumentation dating back to the nineteenth century, particularly by French composers who knew Adolphe Sax. The Raschèr,[16] Amherst,[17] Aurelia,[18] Amstel and Rova Saxophone Quartets are among the best known groups. Historically, the quartets led by Marcel Mule and Daniel Deffayet, saxophone professors at the Conservatoire de Paris, were started in 1928 and 1953, respectively, and were highly regarded. The Mule quartet is often considered to be the prototype for all future quartets due the level of virtuosity demonstrated by its members and its central role in the development of the quartet repertoire. However organised quartets did exist before Mule's ensemble, the prime example being the quartet headed by Eduard Lefebre (1834-1911), former soloist with the Sousa band, in the United States c1904-1911. Other ensembles most likely existed at this time as part of the saxophone sections of the many touring "business" bands that existed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. More recently, the World Saxophone Quartet has become known as the preeminent jazz saxophone quartet. The Rova Saxophone Quartet, based in San Francisco, is noted for its work in the fields of contemporary classical music and improvised music.

There are a few larger all-saxophone ensembles, the most prominent including the 9-member SaxAssault,[19] and Urban Sax, which includes as many as 52 saxophonists. The 6-member Nuclear Whales Saxophone Orchestra owns one of the few E♭ contrabass saxophones, and plays a variety of ensemble pieces including "Casbah Shuffle", a duet for sopranino and contrabass.[20] Very large groups, featuring over 100 saxophones, are sometimes organized as a novelty at saxophone conventions.[21]

Related instruments

Other saxophones

The "contralto" saxophone, similar in size to the orchestral soprano, was developed in the late 20th century by California instrument maker Jim Schmidt.[22] This instrument has a larger bore and a new fingering system, and does not resemble the C melody instrument except for its key and register. Another new arrival to the novelty sax scene is the soprillo sax, a piccolo-sized straight instrument which has the upper speaker hole built into the mouthpiece. The instrument, which extends Sax's original family as it is pitched a full octave higher than the B♭ soprano sax, is manufactured by Benedikt Eppelsheim, of Munich, Germany. There is a rare prototype slide tenor saxophone, but few were ever made. One known company that produced a slide soprano saxophone was Reiffel & Husted, Chicago, ca. 1922 (catalog NMM 5385).[23][24][25]

Similar instruments

A number of saxophone-related instruments have appeared since Sax's original work, most enjoying no significant success. These include the saxello, essentially a straight B♭ soprano, but with a slightly curved neck and tipped bell; the straight alto; and the straight B♭ tenor.[26]) Since a straight-bore tenor is approximately five feet long, the cumbersome size of such a design makes it almost impossible to either play or transport. "King" Saxellos, made by the H. N. White Company in the 1920s, now command prices up to US$4,000. A number of companies, including Rampone & Cazzani and L.A. Sax, are marketing straight-bore, tipped-bell soprano saxophones as saxellos (or "saxello sopranos").

The tubax, developed in 1999 by the German instrument maker Benedikt Eppelsheim,[27] plays the same range, and with the same fingering, as the E♭ contrabass saxophone; its bore, however, is narrower than that of a contrabass saxophone, making for a more compact instrument with a "reedier" tone (akin to the double-reed contrabass sarrusophone). It can be played with the smaller (and more commonly available) baritone saxophone mouthpiece and reeds. Eppelsheim has also produced subcontrabass tubaxes in C and B♭, the latter being the lowest saxophone ever made. Among the most recent developments is the aulochrome, a double soprano saxophone invented by Belgian instrument maker François Louis in 2001.

Bamboo "saxophones"

Although not true saxophones, inexpensive keyless folk versions of the saxophone made of bamboo were developed in the 20th century by instrument makers in Hawaii, Jamaica, Thailand, Indonesia, and Argentina. The Hawaiian instrument, called a xaphoon, was invented during the 1970s and is also marketed as a "bamboo sax," although its cylindrical bore more closely resembles that of a clarinet, and its lack of any keywork makes it more akin to a recorder. Jamaica's best known exponent of a similar type of homemade bamboo "saxophone" was the mento musician and instrument maker 'Sugar Belly' (William Walker).[28] In the Minahasa region of the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, there exist entire bands made up of bamboo "saxophones"[29] and "brass" instruments of various sizes. These instruments are clever imitations of European instruments, made using local materials. Very similar instruments are produced in Thailand.[30][31] In Argentina, Ángel Sampedro del Río and Mariana García have produced bamboo saxophones of various sizes since 1985, the larger of which have bamboo keys to allow for the playing of lower notes.[32]audio

Writing for the saxophone

Music for most saxophones is usually notated using treble clef. The standard written range extends from a B♭ below the staff to an F or F♯ three ledger lines above the staff. There are a few models of soprano saxophone that have a key for high G, and several models of baritone saxophone have an extended bore and key to produce low A; it is also possible to play a low A on any saxophone by blocking the end of the bell, usually with the foot or inside of the left thigh. Notes above F are considered part of the altissimo register of any sax, and can be produced using advanced embouchure techniques and fingering combinations. Sax himself had mastered these techniques; he demonstrated the instrument as having a range of just beyond three octaves up to a (written) high B4.

Because all saxophones use the same key arrangement and fingering to produce a given notated pitch, it is not difficult for a competent player to switch among the various sizes when the music has been suitably transposed. Since the baritone and alto are pitched in E♭, players can read concert pitch music notated in the bass clef by reading it as if it were treble clef and adding three sharps to the key signature. This process, referred to as clef substitution, makes it possible for the baritone or alto to play from parts written for bassoon, tuba, trombone or string bass. This can be useful if a band or orchestra lacks one of those instruments.

Saxophone techniques

Saxophones use wide varieties of saxophone techniques. Some techniques like a "growl" can give a saxophone a rocky sound. Other techniques such as vibrato are commonly used with all music. Some saxophone techniques include:

- Growling

- Vibrato

- Laugh

- Circular breathing

- Flutter tongue

- Pitch bending

Growling is a very popular technique used in rock or aggressive-sounding music. Growling somewhat mimics a growl by singing a note into the sax while playing. Usually the note sung into the sax is a little off pitch to the note that is played.

Vibrato is used in both singing and instrumental music. It sounds like a note being bent upward (usually a half step up) and back down giving a good sounding note. To do vibrato on sax, the player's jaw moves slightly up and down while playing. Vibrato is played at a fairly fast speed. Average speed for vibrato would be an eighth note triplet.

A Laugh on sax is a technique used to mimic a human laugh. A laugh is produced by breathing into the horn as if the player were laughing.

Circular breathing is used to play a very long note (as long as the player can keep the technique up). To circular breathe the player's cheeks are filled with air. When the player runs out of air, she blows the air stored in her cheeks and breathes in through her nose while using the air in your cheeks to catch breath. This technique can be repeated. A saxophonist famous for circular breathing is Kenny G.

Flutter tongue flutters a note fast. To flutter tongue on a sax trill, the player's tongue is fluttered while playing.

Pitch bending is also commonly used in instrumental music. It is used to "bend" a note up and down without changing fingerings. The jaw is tightened and loosened, causing the pitch to rise and fall.

See also

Notes

- ^ "Adolphe Sax". BassSax.com. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "The history of the saxophone". The-Saxophone.com. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ MacGillivray, James (1959). "Recent Advances in Woodwind Fingering Systems". The Galpin Society Journal. 12. The Galpin Society Journal: 68. doi:10.2307/841949. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Jay C. Easton: Saxophone Family Gallery". Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "Contrabass-L, Vol. 1, No. 76". Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "A992". Yanagisawa website. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ "T9937". Yanagisawa website. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ "Saxophone Finishes". Cannonball Musical Instruments. Retrieved 2008-05-01.

- ^ "tenor_sxr90r_shadow". keilwerth website. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

- ^ "PMST-60NS". P. Mauriat website. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ a b "The Horn". JazzBariSax.com.

- ^ "Jazz & Blues Saxophone FAQs". Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "How Brass Instruments are Built". Acoustical Society of America. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ Teal, Larry (1963). The Art of Saxophone Playing. Miami: Summy-Birchard. p. 17. ISBN 0-87487-057-7.

A preference as to material used is up to the individual, and the advantages of each are a matter of controversy. Mouthpieces of various materials which have exactly the same dimensions, including the chamber and outside measurements as well as the facing, play very nearly the same.

- ^ "James Fei: DVD". Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "Raschèr Saxophone Quartet". Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "Amherst Saxophone Quartet". Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "AureliaSax4". Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "The Band". SaxAssault.com. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "About the Nuclear Whales and their music". Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "14th World Saxophone Congress 2006 - Ljubljana - Slovenia". Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "Jim Schmidt's Contralto". Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "The Royal Holland Bell Ringers Collection and Archive". Retrieved 2006-10-23.

- ^ "Slide sax picture at http://www.gs.kunitachi.ac.jp". Retrieved 2006-10-23.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "Slide sax picture at http://www.jasonharron.com". Retrieved 2006-10-23.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "L.A. Sax Straight Models". Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "Tubax E♭ saxophone". Benedikt Eppelsheim Wind Instruments. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "Mento Music: Sugar Belly". Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "Culture & Arts in North Sulawesi, Indonesia". Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "a bio-aesthetic offspring of single reed woodwinds-Dieter Clermont and his Thai partner Khanung Thuanthee build bamboo saxophones in North Thailand since the late 1980s". Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ^ "Thai Bamboo Saxophone". Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "Un Mundo de Bambú". Retrieved 2007-05-07.

Bamboo Saxophone -a bio-aesthetic-offspring of single reed woodwinds http://www.indochinamusic.com/store/index.php?act=viewDoc&docId=1]

References

- Grove, George (2001). Stanley Sadie (ed.). The New Grove Encyclopædia of Music and Musicians (2nd edition ed.). Grove's Dictionaries of Music. pp. Volume 18, pp534–539. ISBN 1561592390.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Horwood, Wally (1992) [1983]. Adolphe Sax, 1814-1894: His Life and Legacy ((Revised edition) ed.). Herts: Egon Publishers. ISBN 0-905858-18-2.

- Howe, Robert (2003). Invention and Development of the Saxophone 1840-55. Journal of the American Musical Instrument Society.

- Kool, Jaap. Das Saxophon (in German). Leipzig: J. J. Weber. (translated to English as Gwozdz, Lawrence (1987). The Saxophone. Egon Publishers Ltd.)

- Kotchnitsky, Léon (1985) [1949]. Sax and His Saxophone (fourth edition ed.). North American Saxophone Alliance.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Lindemeyer, Paul (1996). Celebrating the Saxophone. William Morrow & Co. ISBN 0-688-13518-8.

- Segell, Michael (2005). The Devil's Horn: The Story of the Saxophone, from Noisy Novelty to King of Cool. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-15938-6.

- Thiollet, Jean-Pierre (2004). Sax, Mule & Co. Paris: H & D. ISBN 2-914-26603-0.