Etrog

Etrog is the Hebrew name for the citron or Citrus medica. This is the standard romanization of the original lettering אֶתְרוֹג, which is according to the Sephardic pronunciation. Some follow the Ashkenazi version calling it esrog or esrig, by others it is transliterated as athrog or similar[1].

It is well known as one of the four species used in the rituals associated with the Jewish holiday of Sukkot. Historically the Etrog has been regarded as a major Jewish symbol.

Leviticus 23:40 refers to the etrog as pri eitz hadar (פְּרִי עֵץ הָדָר), which literally means, "a fruit of the beautiful tree." In modern Hebrew, hadar refers to the genus citrus, while Nahmanides (1194 – c. 1270) suggests that the word was the original Hebrew name for the citron. According to him, the word etrog was introduced over time, adapted from the Aramaic. The Arabic name for the citron fruit, itranj (اترنج), mentioned in hadith literature, is also associated with the Hebrew.

Unlike the rest of the species the etrog is so highly praised that it is commonly stored in a silver box, called Esrog-Pushka. After its main role in the ritual on Sukkot, it is a common Ashkenazi custom to eat the etrog on Tu Bishvat in form of a sugared fruit soup which is also including quince[2], or as succade. By this time, they are praying to The Almighty to merit a beautiful Etrog for the upcoming Sukkoth.[3]

Marketability

History

In old Jewish Eastern European communities, the Jews lived in cities far away from fields, and as such had to travel far in order to purchase an etrog. In addition, the etrog was especially rare and thus very expensive, often whole towns would have to share them. In Northern African communities, in Morocco, Tunis and Tangier, the communities were located closer to fields, but the etrog was still fairly expensive. There, instead of one per city, there was one per family. But in both areas, the community would share their etrogs to some extent.

Today, with improved transportation, farming techniques etc., more people have their own. An etrog can cost anywhere from $3 to $500 depending on their quality[4].

Size

The fruit is ready to harvest when it reaches about six inches in length. Although for commercial use it is not harvested before January, when at optimum size – for ritual use it must be picked while still small, in order to reach the market in time. The optimal size is also the best for marketability, as by growing larger it may lose from its beauty. Since the citron blooms several times a season, fruit may be picked during July and August, and even in June.

According to Halacha the fruit must only reach the size of a hen's egg in order to be considered kosher, but larger sizes are preferred as long as they can be held with one hand. Marketwise, a nice size fetches a higher price, as long the fruit is also good in other aspects. If both hands are needed to hold it, it is still kosher, but less desirable.

Colour

The fruit is typically picked while still green, taking advantage of ethylene gas to ripen the fruit in a controlled manner. The same gas is also naturally released from apples, so some growers simply put the fruits in the same box as apples.

Unblemished rind

The etrog used in the mitzvah of the four species must be largely unblemished, with the fewest black specks or other flaws. Extra special care is needed to cut around the leaves and thorns that may scratch the fruit. It is also important to protect the fruit-bearing trees from any dust and carbon, which may get caught in the stomata of the fruit during growth, and may later appear as a black dot.

Shape

The etrog may differ in shape, since the several citron varieties used for that purpose, each bear fruits with a distinct form and shape. Furthermore, a specific variety or even a single tree may also bear fruit in several shapes and sizes. An etrog of completely round shape is not-kosher, whilst a slanted or bent specimen is permissible but not the best. The bearing branch must be arched down with care, in order to get the fruit growing straight in a downward position. Otherwise the fruit will be forced to make the curvature on its own body, while turned downwards because of its increasing weight. This practice must be performed very delicately in order not to break the stiff citron twig.

While many prefer the pyramid shape of variety etrog, and others for the barrel shape of the Diamante, some look for an etrog with a gartel—a hourglass-like strip running around the middle, more commonly found on the Moroccan citron.

According to researchers, this gartel indicates when the bearing tree was infected by a certain virus or viroid, which decreases the albedo on the specific spot. These viroids have been around since the time of Bar Kokhba (circa 130 CE), as obtained from the fact that archaeologists have unearthed a mosaic depicting an etrog with a gartel.[5]

Only the etrog is found to be susceptible to these viroids, proving again that the etrog is genetically pure, and has not changed much over the centuries. [6]

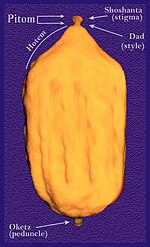

Pitam (Pitom)

An etrog with an intact pitam is considered especially valuable. A pitam is composed of a style (Hebrew: dad), and a stigma (Hebrew: shoshanta), which usually falls off during the growing process. However, varieties that shed off their pitam during growth are also kosher. When only the stigma breaks off, even post-harvest, it could still be considered kosher as long as part of the style has remained attached. If the whole pitam i.e. the stigma and style, are unnaturally broke off till the bottom, it is not kosher for the ritual use.

Many pitams are preserved today thanks to an auxin discovered by Dr. Eliezer E. Goldschmidt, formerly professor of horticulture at the Hebrew University. Working with the picloram hormone in a citrus orchard one day, he discovered to surprise that some of the Valencia oranges found nearby had preserved beautiful, perfect pitams.

Usually a citrus fruit, other than an etrog or citron hybrid like the bergamot, does not preserve its pitam. When it occasionally does, it should at least be dry, sunken and very fragile. In this case the pitams were all fresh and healthy just like those of the Moroccan or Greek citron varieties.

Experimenting with the picloram in a laboratory, Goldschmidt eventually found the correct “dose” to achieve the desired effect: one droplet of the chemical in three million drops of water. This invention is highly appreciated by the Jewish community.[7]

Purity

In order for a citron to be kosher it must be pure, not grafted nor bred with any other species, therefore only a few traditional varieties are used. In addition, the plantations must be under strict rabbinical supervision.

Genetic research

The Citron varieties traditionally used as Etrog, are the Diamante Citron from Italy, the Greek Citron, the Balady Citron from Israel, the Moroccan and Yemenite Citrons.

| Citron varieties |

|---|

|

| Acidic-pulp varieties |

| Non-acidic varieties |

| Pulpless varieties |

| Citron hybrids |

| Related articles |

A general DNA study was arranged by the world-renowned researcher of the etrog, Prof. Goldschmidt and colleagues, who positively testified 12 famous accessions of citron for purity and being genetically related.

As they clarify in their joint publication, this is only referring to the genotypic information which could be changed by breeding for e.g. out cross pollination etc., not about grafting which is not suspected to change anything in the genes.[8]

The Fingered and Florentine Citrons although they are also Citron varieties or maybe hybrids, are not used for the ritual. The Corsican Citron is no longer in use, though it was once used and sacred.

Selection and cultivation

In addition to the above, there are many rabbinical indicators to identify pure etrogs out of possible hybrids. Those traditional specifications were preserved by continues selections accomplished by professional farmers.[9]

The most accepted indicators are as following: 1) a pure etrog has a thick rind, in contrast to its narrow pulp segments which are also almost dry, 2) the outer surface of an etrog fruit is ribbed and warted, and 3) the etrog peduncle is somewhat buried inward; a lemon or different citron hybrid is opposing one or all of the specifications.[10]

A later and not so widely accepted indicator is the orientation of the seed, which should be pointing vertically by an etrog, except if it was strained by its neighbors; by a lemon and hybrids they are positioned horizontally even when there is enough space.[11]

The etrog is typically grown from cuttings that are two to four years old, the tree begins to bear fruit when it is around four years old.[12] If the tree germinates from seeds, it will not fruit for about seven years, and there may be some genetic change to the tree or fruit in the event of seed propagation.[13]

References

- ^ See The Citrus Industry as a common example.

- ^ Recipe

- ^ Aish

- ^ Jerusalemite.net

- ^ Bar-Joseph, M. 2003. Natural history of viroids-horticultural aspects, pp. 246-251. In: Viroids. CSIRO Publication, Collingwood, Victoria, Australia.

- ^ The Search for the Authentic Citron: Historic and Genetic Analysis; HortScienc 40(7):1963-1968. 2005

- ^ Style Abscission in the Citron. American Journal of Botany, Vol. 58, no 1. pp. 14-23

- ^ A brief documentation of this study could be found at the Global Citrus Germplasm Network.

- ^ Article by Professor Goldschmidt, published by Tehumin, summer 5741 (1981), booklet 2, p. 144

- ^ Letter by rabbi Shmuel Yehuda Katzenellenbogen of Padua midst the 16th century, printed in Teshuvat ha'Remo chapter 126

- ^ Shiurey Kneseth Hagdola and Olat Shabbat, cited by Magen Avraham, Orach Chaim chapter 648, comment 23

- ^ Chiri, Alfredo. (2002). Etrog

- ^ Sunkist Website

- Shulchan Aruch, Orach Chaim, 648 and commentaries.

- Citrus Propagation by Ultimate Citrus

- Fact Sheet HS-86 June 1994 by the University of Florida

- CROP PROPAGATION II: SEXUAL PROPAGATION

External links

- The Citrus Variety Collection by the University of California Riverside

- Description of citron and varieties by Purdue University

- Ancient Treasures and the Dead Sea Scrolls

- Mosaic depicting an etrog

- Lulav, Etrog, Shofar and Menorah, 2nd Cent. CE, Ostia Synagogue

- An antique Hebrew coin depicting an etrog

- Etrog Varieties with pictures, from Zeide Reuven Etrog Farm

- More information on the etrog by Milechai.com

- Judaism 101 Information and pictures.

- UJA of Greater Toronto

- The Jewish Daily Forward

- Information on citron varieties Concise.Britannica.com or by InnVista.com

- Pictures homecitrusgrowers.co.uk

- DNA study ActaHort