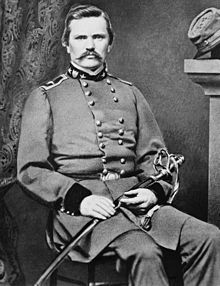

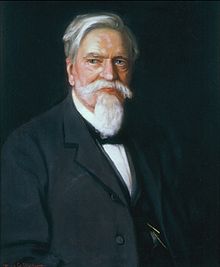

Simon Bolivar Buckner

Simon Bolivar Buckner, Sr. | |

|---|---|

| |

| 30th Governor of Kentucky | |

| In office August 30, 1887 – September 2, 1891 | |

| Lieutenant | James Bryan |

| Preceded by | J. Proctor Knott |

| Succeeded by | John Y. Brown |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 1, 1823 Hart County, Kentucky |

| Died | January 8, 1914 (aged 90) Hart County, Kentucky |

| Resting place | Frankfort Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic National Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Jane Kingsbury Delia Clairborne |

| Children | Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr. |

| Residence | Glen Lily |

| Alma mater | United States Military Academy |

| Profession | Soldier, newspaper editor |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | United States Army Confederate States Army |

| Years of service | 1844–1855 (USA) 1861–1865 (CSA) |

| Rank | Captain (USA) Lieutenant General (CSA) |

| Unit | 2nd Infantry Regiment 6th Infantry Regiment Army of Mississippi |

| Battles/wars | Mexican-American War American Civil War |

Simon Bolivar Buckner (April 1, 1823– January 8, 1914) was a soldier who fought in United States Army in the Mexican-American War and in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. He later served as the thirtieth governor of Kentucky.

After graduating from the United States Military Academy at West Point, Buckner became an instructor there. He took a hiatus from teaching to serve in the Mexican-American War, participating in many of the major battles of that conflict. He resigned from the army in 1855 to manage his father-in-law's real estate in Chicago, Illinois. He returned to his native state in 1857 and was appointed adjutant general by Governor Beriah Magoffin in 1861. In this position, he tried to enforce Kentucky's neutrality policy in the early days of the Civil War. When the state's neutrality was breached, Buckner accepted a commission in the Confederate Army after declining a similar commission to the Union Army. In 1862, he famously accepted Ulysses S. Grant's demand for an "unconditional surrender" at the Battle of Fort Donelson. He participated in Braxton Bragg's failed invasion of Kentucky and near the end of the war became chief of staff to Edmund Kirby Smith in the Trans-Mississippi Department.

In the years following the war, Buckner became active in politics. He was elected governor of Kentucky in 1887. It was his second campaign for that office. His term was plagued by violent feuds in the eastern part of the state, including the Hatfield-McCoy feud and the Rowan County War. His administration was rocked by scandal when state treasurer James "Honest Dick" Tate absconded with $250,000 from the state's treasury. As governor, Buckner became known for vetoing special interest legislation. In the 1888 legislative session alone, he utilized more vetoes than the previous ten governors combined. In 1895, he made an unsuccessful bid for a seat in the U.S. Senate. The following year, he joined the National Democratic Party, or "Gold Democrats", who favored a sound money policy over the Free Silver position of the mainline Democrats. He was the Gold Democrats' candidate for Vice President of the United States in the 1896 election, but polled just over one percent of the vote on a ticket with John Palmer. He never again sought public office and died of uremic poisoning on January 8, 1914.

Early life

Simon B. Buckner, Sr. was born at Glen Lily, his family's estate near Munfordville, Kentucky.[1] He was the third child and second son born to Aylett Hartswell and Elizabeth Ann (Morehead) Buckner.[2] Named after the "South American soldier and statesman, Simón Bolívar, then at the height of his power",[3] the boy did not begin school until age 9 when he enrolled at a private school in Munfordville.[4] Buckner's father was an iron worker, but found that Hart County did not have sufficient timber to fire his iron furnace.[5] Consequently, in 1838, he moved the family to southern Muhlenberg County where he organized an iron-making corporation.[5] Buckner attended school in Greenville, and later at Christian County Seminary in Hopkinsville.[6][1]

On July 1, 1840, Buckner enrolled at the United States Military Academy.[7] In 1844 he graduated eleventh in his class of 25 and was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Infantry Regiment.[7][8] He was assigned to garrison duty at Sackett's Harbor until August 28, 1845, when he returned to the Academy to serve as an assistant professor of geography, history and ethics.[9]

Service in the Mexican-American War

In May 1846, Buckner resigned his teaching position to fight in the Mexican-American War, enlisting with the 6th Infantry Regiment. His early duties included recruiting soldiers and bringing them to the Texas border. In November 1846, he was ordered to join his company in the field; he met them en route between Monclova and Parras. The company joined John E. Wool at Saltillo. In January 1847, Buckner was ordered to Vera Cruz with William J. Worth's division. While Zachary Taylor besieged Vera Cruz, Buckner's unit engaged a few thousand Mexican cavalry at a nearby town called Amazoque.[10]

On August 8, 1847, Buckner was made quartermaster of the 6th Infantry Regiment. Shortly thereafter, he participated in battles at San Antonio and Churubusco, being slightly wounded in the latter battle. He was appointed a brevet first lieutenant for gallantry at Churubusco and Contreras, but declined the honor in part because reports of his participation at Contreras were in error—he had been fighting in San Antonio at the time. Later, he was offered and accepted the same rank solely based on his conduct at Churubusco.[11]

Buckner was again cited for gallant conduct at the Battle of Molino del Rey, and was brevetted to captain. He participated in the Battle of Chapultepec, the Battle of Belen Gate, and the storming of Mexico City. At the conclusion of the war, American soldiers served as an army of occupation for a time, leaving soldiers time for leisure activities. Buckner joined the Aztec Club, and in April 1848 was a part of the successful expedition of Popocatépetl, a volcano southeast of Mexico City.[12]

Post-war career

After the war, Buckner accepted an invitation to return to West Point to teach infantry tactics.[13] Just over a year later, he resigned the post in protest over the academy's compulsory chapel attendance policy.[14] Following his resignation, he was assigned to a recruiting post at Fort Columbus.[15]

Buckner married Mary Jane Kingsbury on May 2, 1850 at her aunt's home in Old Lyme, Connecticut. Shortly after marriage, he was assigned to Fort Snelling and later to Fort Atkinson on the Arkansas River in present-day Kansas. On December 31, 1851, he was promoted to first lieutenant, and on November 3, 1852, he was elevated to captain of the commissary department. Previously, he had attained only a brevet to these ranks. Buckner gained such a reputation for fair dealings with the Indians, that the Oglala Lakota tribe called him Young Chief, and their leader, Yellow Bear, refused to treat with anyone but Buckner.[16]

Just before leaving the army, Buckner helped an old friend from West Point and the Mexican-American War, Captain Ulysses S. Grant, by covering his expenses at a local hotel until money arrived from Ohio to pay for his passage home. On March 26, 1855 Buckner resigned from the army to work with his father-in-law, who had extensive real estate holdings in Chicago, Illinois. When his father-in-law died in 1856, Buckner inherited his property and moved to Chicago to manage it.[17]

Still interested in military affairs, Buckner joined the Illinois State Militia of Cook County as a major. On April 3, 1857, he was appointed adjutant general of Illinois by Governor William Henry Bissell. He resigned the post in October of the same year. Following the Mountain Meadows massacre, a regiment of Illinois volunteers organized for potential service in a campaign against the Mormons. Buckner was offered command of the unit and a promotion to the rank of colonel. He accepted the position, but predicted that the unit would not see action. His prediction proved correct, as negotiations between the federal government and Mormon leaders eased tensions between the two.[18]

In late 1857, Buckner and his family returned to his native state and settled in Louisville. Buckner's daughter, Lily, was born there on March 7, 1858. Later that year, a Louisville militia known as the Citizens' Guard was formed, and Buckner was made its captain. He served in this capacity until 1860, when the Guard was incorporated into the Kentucky State Guard's Second Regiment.[19]

Civil War

In 1861 Kentucky governor Beriah Magoffin appointed Buckner adjutant general, promoted him to major general, and charged him with revising the state's militia laws.[20][21] The state was torn between Union and Confederacy, with the legislature supporting the former and the governor the latter. This led the state to declare it was officially neutral. Buckner assembled 61 companies to defend Kentucky's neutrality.[20]

The state board that controlled the militia considered it to be pro-secessionist and ordered it to store its arms.[22] On July 20, 1861, Buckner resigned from the state militia, declaring that he could no longer perform his duties due to the board's actions.[22] That August he was offered a commission as a brigadier general in the Union Army, but declined.[23] After Confederate General Leonidas Polk captured Columbus, Kentucky, violating the state's neutrality, Buckner accepted a commission as a brigadier general in the Confederate States Army on September 14, 1861, and was followed by many of the men he formerly commanded in the state militia.[24][8] He became a division commander in the Army of Central Kentucky under Brig. Gen. William J. Hardee and was stationed in Bowling Green, Kentucky.[25]

Fort Donelson

After Ulysses S. Grant captured Fort Henry on the Tennessee River in February 1862, he turned his sights on nearby Fort Donelson on the Cumberland. Western Theater commander Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston sent Buckner to be one of four brigadier generals defending the fort. In overall command was the influential politician and military novice John B. Floyd; Buckner's peers were Gideon J. Pillow and Bushrod Johnson.[26]

Buckner's division defended the right flank of the Confederate line of entrenchments that surrounded the fort and the small town of Dover, Tennessee. On February 14, the Confederate generals decided they could not hold the fort and planned a breakout attempt, hoping to join with Johnston's army, now in Nashville. At dawn the following morning, Pillow launched a strong assault against the right flank of Grant's army, pushing it back 1 to 2 miles. Buckner, not confident of his army's chances and not on good terms with Pillow, held back his supporting attack for over two hours, giving Grant's men time to bring up reinforcements and reform their line. Buckner's delay did not prevent the Confederate attack from opening a corridor for an escape from the besieged fort. At this time, however, Floyd and Pillow combined to undo the day's work by ordering the troops back to their trench positions.[27]

Late that night the generals held a council of war in which Floyd and Pillow expressed satisfaction with the events of the day, but Buckner convinced them that they had little realistic chance to hold the fort or escape from Grant's army, which was receiving steady reinforcements. His defeatism carried the meeting. General Floyd, concerned he would be tried for treason if captured by the North, sought Buckner's assurance that he would be given time to escape with some of his Virginia regiments before the army surrendered. Buckner agreed and Floyd offered to turn over command to his subordinate, Pillow. Pillow immediately declined and passed command to Buckner, who agreed to stay behind and surrender. Pillow and Floyd were able to escape, as did cavalry commander Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest.[28]

That morning, Buckner sent a messenger to the Union Army requesting an armistice and a meeting of commissioners to work out surrender terms.[29] He may have been hoping Grant would offer generous terms, remembering the assistance he gave Grant when he was destitute, but Grant had no sympathy for his old friend and his reply included the famous quotation, "No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works."[30] To this, Buckner responded:

SIR:—The distribution of the forces under my command, incident to an unexpected change of commanders, and the overwhelming force under your command, compel me, notwithstanding the brilliant success of the Confederate arms yesterday, to accept the ungenerous and unchivalrous terms which you propose.[31]

Grant was courteous to Buckner following the surrender and offered to loan him money to see him through his impending imprisonment, but Buckner declined. The surrender was a humiliation for Buckner personally, but also a strategic defeat for the Confederacy, which lost more than 12,000 men and much equipment, as well as control of the Cumberland River, which led to the evacuation of Nashville.[32]

Invasion of Kentucky

While Buckner was a Union prisoner of war at Fort Warren in Boston, Kentucky Senator Garrett Davis unsuccessfully sought to have him tried for treason.[20] On August 15, 1862, Buckner was exchanged for Union Brig. Gen. George A. McCall.[8] The following day he was promoted to major general.[33] He was assigned to Braxton Bragg's Army of Mississippi in Tennessee.[34]

Days after Buckner joined Bragg, both Bragg and Edmund Kirby Smith began an invasion of Kentucky. As Bragg pushed north, his first encounter was in Buckner's home town of Munfordville. The small town was important for Union forces to maintain communication with Louisville if they decided to press southward to Bowling Green and Nashville. A small force under the command of Col. John T. Wilder guarded the town. Though vastly outnumbered, Wilder refused requests to surrender on September 12 and September 14. By September 17, however, Wilder recognized his difficult position. In an unusual move, Wilder agreed to be blindfolded and brought to Buckner. When he arrived, he told Buckner that he (Wilder) was not a military man and had come to ask him what he should do. Flattered, Buckner showed Wilder the strength and position of the Confederate forces, which outnumbered Wilder's men almost 5-to-1. Seeing the hopeless situation he was in, Wilder informed Buckner that he wanted to surrender.[35]

Bragg's men continued northward to Bardstown where they rested and sought supplies and recruits. Meanwhile, Don Carlos Buell's men, the main Union force in the state, were pressing toward Louisville. Based on intelligence gained from a spy in Buell's army, Buckner advised Bragg that Buell was still ten miles from Louisville in the town of Mackville. He urged Bragg to engage Buell there before he reached Louisville, but Bragg declined. Buckner then asked Leonidas Polk to request that Bragg concentrate his forces and attack Perryville, but again, Bragg refused. Instead, he divided his army and scattered them in four different directions. Finally, on October 8, 1862, Bragg's remaining forces (about one-third of the original number) engaged Alexander McCook and began the Battle of Perryville. Buckner fought under General Hardee during this battle, and reports from Hardee, Polk, and Bragg all praise Buckner's efforts. His gallantry was for naught, however, as Perryville ended in a draw that was costly for both sides.[36]

Later Civil War service

Following the Battle of Perryville, Buckner was reassigned to command the District of the Gulf, fortifying the defenses of Mobile, Alabama.[8] He remained there until late April 1863, when he was ordered to take command of the Army of East Tennessee.[37] On May 11, 1863, he arrived in in Knoxville and assumed command the following day.[38] Shortly thereafter, his department was incorporated into the Department of Tennessee under Gen. Bragg.[39]

In late August, Union Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside approached Buckner's position at Knoxville. Buckner called for reinforcements from Bragg at Chattanooga, but Bragg was being threatened by forces under William Rosecrans and could not spare any of his men. Bragg ordered Buckner to fall back to the Hiwassee River. From there, Buckner's unit traveled to Bragg's supply base at Ringgold, Georgia, then on to Lafayette and Chickamauga. Bragg was also forced from Chattanooga and joined Buckner at Chickamauga. On September 19 and 20, the Confederate forces were attacked but emerged victorious at the Battle of Chickamauga.[40]

After Chickamauga, Rosecrans and his men fortified Chattanooga and waited for reinforcements.[41] Bragg held an ineffective siege against Chattanooga, but refused to take any further action against Union forces there.[42] Many of Bragg's subordinates, including Buckner, advocated that Bragg be relieved of command.[43] Bragg retaliated by reducing Buckner to division command and abolishing the Department of East Tennessee.[44]

Due to illness, Buckner was given a leave of absence following Chickamauga. He spent his leave in Virginia, engaging in routine work and recovering his strength. After he recovered, Buckner joined Lt. Gen. James Longstreet in the Siege of Knoxville.[8] He was briefly given command of John Bell Hood's division, and on March 8, 1864, he was given command of the reestablished Department of East Tennessee.[45] The department was a shell of its former self—less than one-third its original size, badly equipped, and in no position to mount an offensive.[46] Buckner was virtually useless to the Confederacy here, and on April 28, he was ordered to join Edmund Kirby Smith in the Trans-Mississippi Department of the Confederacy.[47]

Shortly after Buckner arrived at Smith's headquarters in Shreveport, Louisiana, Smith began requesting a promotion for him.[48] The promotion to lieutenant general came on September 20.[44] Smith placed Buckner in charge of the critical but difficult task of selling the department's cotton through enemy lines.[49]

As news of Gen. Robert E. Lee's surrender reached the department, soldiers deserted the Confederacy in droves. On April 19, 1865, Smith consolidated the District of Arkansas with the District of West Louisiana; the combined district was put under Buckner's command. On May 9, Smith made Buckner his chief of staff. Rumors began to swirl in both Union and Confederate camps that Smith and Buckner would not surrender, but would fall back to Mexico with soldiers who remained loyal to the Confederacy. Though Smith did cross the Rio Grande, he learned on his arrival that Buckner had traveled to New Orleans on May 26 and arranged terms of surrender.[50] At Fort Donelson, Buckner had become the first Confederate general of the war to surrender an army; at New Orleans, he became the last.[51] The surrender became official when Smith endorsed it on June 2.[51]

Post-war life

After his army surrendered, Buckner was paroled in Shreveport, Louisiana, on June 9, 1865. The terms of his parole prevented his return to Kentucky for three years, so he lived in New Orleans and worked on the staff of the Daily Crescent newspaper.[8] Further, he engaged in business with a merchant firm and served on the board of directors of a fire insurance company.[52] He became president of the insurance company in 1867.[52] His wife and daughter joined him in the winter months of 1866 and 1867, but he sent them back to Kentucky in the summers because of the frequent outbreaks of cholera and yellow fever.[53]

Buckner returned to Kentucky when he was eligible in 1868 and became editor of the Louisville Courier.[8] Like most former Confederate officers, he petitioned the United States Congress for the restoration of his civil rights as was provided for under the terms of the 14th Amendment. He recovered most of his property through lawsuits and regained much of his wealth through shrewd business deals.[1]

After five years of suffering with tuberculosis, Buckner's wife died on January 5, 1874. The widowed Buckner continued to live in Louisville until 1877 when he and his daughter returned to the family estate in Munfordville. His sister, a recent widow, also returned to the estate in 1877. For six years, these three inhabited and repaired the house and grounds of Glen Lily, which had been neglected during the war and its aftermath. On June 14, 1883, Lily Buckner married Morris B. Belknap of Louisville, and the couple made their residence in Louisville. On October 10 of the same year, Buckner's sister died, and he was left alone.[54]

Political career

Buckner had a keen interest in politics and friends had been urging him to run for governor since 1867, even while terms of his surrender confined him to Louisiana. Unwilling to violate these terms, he instructed a friend to withdraw his name from consideration if it was presented. In 1868, he was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention that nominated Horatio Seymour for president.[55] Though Buckner had favored George H. Pendleton, he loyally supported the party's nominee throughout the campaign.[56]

In 1883, Buckner was a candidate for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination.[57] Other prominent candidates included Congressman Thomas Laurens Jones, former congressman J. Proctor Knott, and Louisville mayor Charles Donald Jacob.[57] Buckner consistently ran third in the first six ballots, but withdrew his name from consideration before the seventh ballot.[57][58] The delegation from Owsley County switched their support to Knott, starting a wave of defections that resulted in Jones' withdrawal and Knott's unanimous nomination.[57] Knott went on to win the general election and appointed Buckner to the board of trustees for the Kentucky Agricultural and Mechanical College (later the University of Kentucky) in 1884.[59] At that year's state Democratic convention, he served on the committee on credentials.[60]

On June 10, 1885, Buckner married Delia Claiborne of Richmond, Kentucky.[61] Buckner was sixty-two; Claiborne was twenty-eight.[60] Their son, Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr., was born on July 18, 1886.[62]

Governor of Kentucky

Delegates to the 1887 state Democratic convention nominated Buckner unanimously for the office of governor. A week later, the Republicans chose William O. Bradley as their candidate. The Prohibition Party and the Union Labor Party also nominated candidates for governor. The official results of the election gave Buckner at plurality of 16,797 over Bradley.[63]

Buckner proposed a number of progressive ideas, most of which were rejected by the legislature. Among his successful proposals were the creation of a state board of tax equalization, creation of a parole system for convicts, and codification of school laws. His failed proposals included creation of a department of justice, greater local support for education and better protection for forests.[64]

Much of Buckner's time was spent trying to curb violence in the eastern part of the state. When he was inaugurated, a bloody feud known as the Rowan County War was ongoing. Residents of Rowan County formed a posse and on June 22, 1888, killed several of the leaders of the feud. Though this essentially ended the feud, the violence had been so bad that Buckner's adjutant general recommended that the Kentucky General Assembly dissolve Rowan County, though this suggestion was not acted upon. In 1888, a posse from Kentucky entered West Virginia and killed a leader of the Hatfield clan in the Hatfield-McCoy feud. This caused a political conflict between Buckner and Governor Emanuel Willis Wilson of West Virginia, who complained that the raid was illegal. The matter was adjudicated in federal court, and Buckner was cleared of any connection to the raid. Later in Buckner's term, feuds broke out in Harlan, Letcher, Perry, Knott, and Breathitt counties.[65]

A major scandal erupted in 1888 when Buckner ordered a routine audit of the state's finances which had been neglected for years.[1] The audit showed that the state's longtime treasurer, James "Honest Dick" Tate, had been mismanaging and embezzling the state's money since 1872.[1] Faced with the prospect that his malfeasance would be discovered, Tate absconded with nearly $250,000 of the state's money.[1] He was never found.[66] The General Assembly immediately began impeachment hearings against Tate, convicted him in absentia, and removed him from office.[66] State auditor Fayette Hewitt was censured for neglecting the duty of his office, but was not implicated in Tate's theft or disappearance.[67]

During the 1888 session of the General Assembly, 1,571 bills were passed, exceeding the total passed by any other session in the state's history. Only about 150 of these bills were of a general nature; the rest were special interest bills passed for the private gain of legislators and those in their constituencies. Buckner vetoed sixty of these special interest bills, more than had been vetoed by the previous ten governors combined. Only one of these vetoes was overridden by the legislature. Ignoring Buckner's clear intent to veto special interest bills, the 1890 legislature passed three hundred more special interest bills than had its predecessor. Buckner vetoed fifty of these. His reputation for rejecting special interest bills led the Kelley Axe Factory, the largest axe factory in the country at the time, to present him with a ceremonial "Veto Hatchet".[68]

When a tax cut passed over Buckner's veto in 1890 drained the state treasury, the governor loaned the state enough money to remain solvent until tax revenue came in.[1] Later that year, he was chosen as a delegate to the state's constitutional convention.[1] In this capacity, he unsuccessfully sought to extend the governor's appointment powers and levy taxes on churches, clubs, and schools that made a profit.[69]

Later career

After his term as governor, Buckner returned to Glen Lily.[1] He was one of four candidates nominated for a seat in the U.S. Senate in 1895—the others being the incumbent, J. C. S. Blackburn; outgoing governor John Y. Brown; and congressman James B. McCreary.[70] The Democratic party split over the issue of bimetalism.[71] Buckner advocated for a gold standard, but the majority of Kentuckians advocated "Free Silver".[72] Seeing that he would not be able to win the seat in light of this opposition, he withdrew from the race in July 1895.[72] In spite of his withdrawal, he still received 9 of the 134 votes cast in the General Assembly.[73]

At the 1896 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, the Democrats nominated William Jennings Bryan for president and adopted a platform calling for the free coinage of silver. Sound money Democrats opposed Bryan and the free silver platform. They formed a new party—the National Democratic Party, or Gold Democrats—which Buckner joined. At the new party's state convention in Louisville, Buckner's name was proposed as a candidate for vice president. He was given the nomination without opposition at the party's national convention in Indianapolis. Former Union general John Palmer was chosen as the party's nominee for president.[74]

Palmer and Buckner both had reputations as independent executives while serving as governors of their respective states. Because they had served on opposite sides during the Civil War, their presence on the same ticket emphasized national unity. The ticket was endorsed by several major newspapers including the Chicago Chronicle, Louisville Courier-Journal, Detroit Free Press, Richmond Times, and New Orleans Picayune. Despite these advantages, the ticket was hurt by the candidates' ages, Palmer being 79 and Buckner 73. Further, some supporters feared that voting for the National Democrat ticket would be a wasted vote and might even throw the election to Bryan. Ultimately, Palmer and Buckner received just over 1 percent of the vote in the election.[75]

Following this defeat, Buckner retired to Glen Lily but remained active in politics. Though he always claimed membership in the Democratic party, he opposed the machine politics of William Goebel, his party's gubernatorial nominee in 1899. In 1903, he supported his son-in-law, Morris Belknap, for governor against Goebel's lieutenant governor, J. C. W. Beckham. When the Democrats again nominated William Jennings Bryan in the 1908 presidential election, Buckner openly supported Bryan's opponent, Republican William Howard Taft.[76]

At 80 years of age, Buckner memorized five of Shakespere's plays because cataracts threatened to blind him, but an operation saved his sight.[69] On a visit to the White House in 1904, Buckner asked President Theodore Roosevelt to appoint his only son as a cadet at West Point, and Roosevelt quickly agreed.[77] His son would later serve in the U.S. Army and be killed at the Battle of Okinawa during World War II.[78]

Following the deaths of Stephen D. Lee and Alexander P. Stewart in 1908, Buckner became the last surviving Confederate soldier with the rank of lieutenant general.[79] The following year, he visited his son, who was stationed in Texas, and toured old Mexican-American War battlefields where he had served.[71] In 1912, his health began to fail.[71] He died on January 8, 1914, after a being ill for a week with uremic poisoning.[71] He was buried in Frankfort Cemetery in Frankfort, Kentucky.[21]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kleber, p. 136

- ^ Stickles, p. 4

- ^ Stickles, p. 5

- ^ Stickles, p. 6

- ^ a b Stickles, p. 7

- ^ Stickles, p. 9

- ^ a b Harrison, p. 119

- ^ a b c d e f g Eicher, pp. 151–52.

- ^ Stickles, p. 15, 24

- ^ Stickles, pp. 16–17

- ^ Stickles, p. 17

- ^ Stickles, pp. 17–19

- ^ Stickles, p. 20

- ^ Stickles, p. 22

- ^ Stickles, p. 23

- ^ Stickles, pp. 25–29

- ^ Stickles, pp. 34–37

- ^ Stickles, p. 38

- ^ Stickles, pp. 41–43

- ^ a b c Powell, p. 68

- ^ a b "Kentucky Governor Simon Bolivar Buckner"

- ^ a b Stickles, p. 78

- ^ Harrison, p. 120

- ^ Gott, p. 37.

- ^ Gott, p. 38.

- ^ Gott, pp. 133–35.

- ^ Gott, pp. 191–217.

- ^ Gott, pp. 238–49.

- ^ Stickles, p. 164

- ^ Stickles, pp. 165–166

- ^ Gott, p. 257.

- ^ Gott, pp. 262–67.

- ^ Stickles, p. 192

- ^ Stickles, p. 194

- ^ Stickles, pp. 194–202

- ^ Stickles, pp. 204–208

- ^ Stickles, p. 213

- ^ Stickles, p. 216

- ^ Stickles, p. 220

- ^ Stickles, pp. 226–231

- ^ Stickles, p. 231

- ^ Stickles, p. 232

- ^ Stickles, pp. 232–233

- ^ a b Hewitt, pp. 140–41.

- ^ Stickles, pp. 241–249

- ^ Stickles, p. 250

- ^ Stickles, p. 252

- ^ Stickles, p. 256

- ^ Stickles, p. 262

- ^ Stickles, p. 265–270

- ^ a b Foote, p. 1021

- ^ a b Stickles, p. 282

- ^ Stickles, p. 281

- ^ Stickles, pp. 313–322

- ^ Stickles, p. 297

- ^ Stickles, p. 298, 318

- ^ a b c d Tapp, p. 213

- ^ Stickles, p. 319

- ^ Stickles, pp. 322–323

- ^ a b Stickles, p. 323

- ^ Stickles, p. 324

- ^ Stickles, p. 332

- ^ Stickles, pp. 336–344

- ^ Harrison, pp. 120–121

- ^ Stickles, pp. 348–355, 367

- ^ a b Stickles, p. 358

- ^ Stickles, p. 355

- ^ Stickles, pp. 360–361, 374–375

- ^ a b Harrison, p. 121

- ^ Stickles, p. 402

- ^ a b c d Harrison, p. 122

- ^ a b Stickles, p. 403

- ^ Tapp, p. 357

- ^ Stickles, pp. 408–409

- ^ Beito, pp. 563–566

- ^ Stickles, pp. 416–421

- ^ Stickles, pp. 420–421

- ^ Kleber, p. 137

- ^ Stickles, p. 421

References

- Beito, David T. (2000)). "Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896-1900". Independent Review. 4: 555–75. Retrieved 2009-08-26.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Eicher, John H. (2001). Civil War High Commands. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804736413.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Foote, Shelby (1974). The Civil War: A Narrative: Red River to Appomatox. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-74622-8.

- Gott, Kendall D. (2003). Where the South Lost the War: An Analysis of the Fort Henry—Fort Donelson Campaign, February 1862. Stackpole books. ISBN 0811700496.

- Harrison, Lowell H. (2004). Lowell H. Harrison (ed.). Kentucky's Governors. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0813123267.

- Hewitt, Lawrence L. (1991). "Simon Bolivar Buckner". In Davis, William C., and Julie Hoffman (ed.). The Confederate General. Vol. 1. National Historical Society. ISBN 0918678633.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - "Kentucky Governor Simon Bolivar Buckner". National Governors Association. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- Kleber, John E., ed. (1992). The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0813117720.

- Powell, Robert A. (1976). Kentucky Governors. Danville, Kentucky: Bluegrass Printing Company. OCLC 2690774.

- Stickles, Arndt M. (1940). Simon Bolivar Buckner: Borderland Knight. University of North Carolina Press. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

- Tapp, Hambleton (1977). Kentucky: Decades of Discord, 1865–1900. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0916968057. Retrieved 2009-05-30.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Warner, Ezra J. (1959). Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0807108235.

Further reading

- Grant, Ulysses S., Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant, Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885–86, ISBN 0-914427-67-9.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

External links

- Interview with Buckner

- "Simon Bolivar Buckner: A Skillful and Judicious General"– Article by Civil War historian/author Bryan S. Bush

- 1823 births

- 1914 deaths

- American Civil War prisoners of war

- American military personnel of the Mexican-American War

- Burials in Frankfort Cemetery

- Confederate Army generals

- Deaths from renal failure

- Governors of Kentucky

- Kentucky Democrats

- Members of the Aztec Club of 1847

- People from Hart County, Kentucky

- People of Kentucky in the American Civil War

- United States Army officers

- United States Military Academy alumni