Cro-Magnon rock shelter

The term Cro-Magnon (Template:Pron-en, French [kʀomaɲɔ̃]) refers to one of the main types of early modern humans of the European Upper Paleolithic. Current dating of Cro-Magnon bones point to more recent date 17,000 years. Earliest known remains of Cro-Magnon like humans are dated to 30,000 radiocarbon years. The name is taken from the cave of Crô-Magnon in southwest France, where the first specimen was found.

The Cro-Magnon term falls outside the usual naming conventions for early humans and is often used in a general sense to describe the oldest modern people in Europe, while remaining, anthropologically speaking, a specific (but very frequent) subtype among the fossil remains. In recent scientific literature the term "European early modern humans" is used instead.

The oldest definitely dated European early modern humans (EEMH) specimen [1] with modern and archaic, possibly Neanderthal, mosaic of traits is Oase 1 from 34,000–36,000 14C years ago.[2]

Assemblages and specimens

The geologist Louis Lartet discovered the first five skeletons of this type in March 1868 in the Cro-Magnon rock shelter. Other specimens have since come to light in other parts of Europe and neighboring areas.

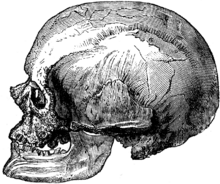

Cro-Magnon 1

Cro-Magnon 1 was discovered in rock shelter at Les Eyzies, Dordogne, France. The type specimen from this find is Cro-Magnon 1 dated 28,000 years BP[3](27.680±270 BP). The skeletons showed the same high forehead, upright posture and slender (gracile) skeleton as modern humans.

The condition and placement of the remains of Cro-Magnon 1 along with pieces of shell and animal tooth in what appears to have been pendants or necklaces raises the question of whether they were buried intentionally. If Cro-Magnons buried their dead intentionally it suggests they had a knowledge of ritual, by burying their dead with necklaces and tools, or an idea of disease and that the bodies needed to be contained.[4]

Analysis of the pathology of the skeletons shows that the humans of this period led a physically difficult life. In addition to infection, several of the individuals found at the shelter had fused vertebrae in their necks, indicating traumatic injury; the adult female found at the shelter had survived for some time with a skull fracture. As these injuries would be life threatening even today, this suggests that Cro-Magnons believed in community support and took care of each others' injuries.[4]

Oase 1

The oldest EEMH remains are from Peştera cu Oase near the Iron Gates in the Danubian corridor. Oase 1 holotype revealed specific traits combining a variety of archaic Homo, derived early modern humans, and possibly Neanderthal features. Modern human attributes place it close to European early modern humans among Late Pleistocene samples. The fossil belongs to the few findings in Europe which could be directly dated and is considered the oldest known early modern human fossil from Europe. Two laboratories independently yielded collagen 14C averaging to 34,950, +990, and –890 B.P.[5] The Oase 1 mandible was discovered February 16, 2002.

Other

All EEMH dates are direct fossil dates provided in 14C years B.P. [6]

- Kostenki 1 = 32,600 ± 1,100. tibia and fibula[6][7][8]

- Mladeč = 31 k 14C years[9],

- Mladeč 2 = 31,320 +410, -390 [6]

- Mladeč 9a = 31,500 +420, -400 [6]

- Mladeč 8 = 30,680 +380, -360 [6]

- Muierii 2 = 30,150 ± 800, cranial and postcranial remains [6]

- Cioclovina 1 = 29,000 ± 700, cranium [6][10]

- Kent's Cavern 4 > 30,900 ± 900 [6]

Not direct dates. Rediocarbon dated were elements from adjacent layers.

Calendar years

- Abrigo do Lagar Velho 24 k [11].

Other sites, assemblages or specimens: Brassempouy, La Rochette, Vogelherd. Engis, Hahnöfersand, St. Prokop, Velika Pećina [12]

Cro-Magnon life

Cro-Magnon were anatomically modern, only differing from their modern day descendants in Europe by their more robust physiology and slightly larger cranial capacity.[13] Of modern nationalities, Finns are closest to Cro-Magnons in terms of anthropological measurements.[14]

Surviving Cro-Magnon artifacts include huts, cave paintings, carvings and antler-tipped spears. The remains of tools suggest that they knew how to make woven clothing. They had huts, constructed of rocks, clay, bones, branches, and animal hide/fur. These early humans used manganese and iron oxides to paint pictures and may have created the first calendar around 15,000 years ago[15].

The flint tools found in association with the remains at Cro-Magnon have associations with the Aurignacian culture that Lartet had identified a few years before he found the skeletons.

The Cro-Magnons are often blamed for causing Neanderthals extinction. Qafzeh humans seem to have coexisted with Neanderthals for up to 60,000 years in the Levant[16] although Qafzeh are logical representative for subsaharan Africans but not for Cro-Magnon and subsequent Europeans[17]. Earlier studies[18] argue for more than 15,000 years of Neanderthal and EEMH coexistence in France[19]; newer for east-west cline of patterns between Neanderthals and EEMH. Additionally the observed reversal of Châtelperronian over Aurignacian cultures may be mistaken conclusion based on interstratified paleo-layers, or layers of sediments disrupted by earlier quasi scientific digs in cave.[20]

Genetics

A 2003 sequencing on two Cro-Magnons, 23 and 24,000 years old Pelosi 1 and 2, mitochondrial DNA, published by an Italo-Spanish research team led by David Caramelli, identified the mtDNA as Haplogroup N.[21] Haplogroup N is found among modern populations of the Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia, and its descendant haplogroups are found among modern North African, Eurasian, Polynesian and Native American populations.[22]

See also

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- List of human evolution fossils

- Neanderthal interaction with Cro-Magnons

- Earth's Children, a series of historical fiction novels written by Jean M. Auel, taking place in ancient Europe

- The Inheritors, a 1955 novel by William Golding about the extinction of Homo Neanderthalensis through conflict with Cro Magnon civilisation

- The Man from Earth, a 2007 motion picture in which a self-described Cro-Magnon reveals himself to his closest friends

References

- ^ Trinkaus, E (2004). "European early modern humans and the fate of the Neandertals" (Free full text). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (18): 7367–72. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702214104. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1863481. PMID 17452632.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Trinkaus, E; Moldovan, O; Milota, S; Bîlgăr, A; Sarcina, L; Athreya, S; Bailey, Se; Rodrigo, R; Mircea, G; Higham, T; Ramsey, Cb; Van, Der, Plicht, J (2003). "An early modern human from the Peştera cu Oase, Romania" (Free full text). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (20): 11231–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.2035108100. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 208740. PMID 14504393.

{{cite journal}}: Text "quote: ...it has unilateral mandibular foramen lingular bridging, an apparently derived Neandertal feature. It therefore presents a mosaic of archaic, early modern human and possibly Neandertal morphological features, emphasizing both the complex population dynamics of modern human dispersal into Europe and the subsequent morphological evolution of European early modern humans." ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [1]

- ^ a b Museum of Natural History

- ^ Trinkaus, E; Moldovan, O; Milota, S; Bîlgăr, A; Sarcina, L; Athreya, S; Bailey, Se; Rodrigo, R; Mircea, G; Higham, T; Ramsey, Cb; Van, Der, Plicht, J (2003). "An early modern human from the Peştera cu Oase, Romania" (Free full text). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (20): 11231–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.2035108100. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 208740. PMID 14504393.

When multiple measurements are undertaken, the mean result can be determined through averaging the activity ratios. For Oase 1, this provides a weighted average activity ratio of 〈14a〉 = 1.29 ± 0.15%, resulting in a combined OxA-GrA 14C age of 34,950, +990, and –890 B.P.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Higham, T; Ramsey, Cb; Karavanić, I; Smith, Fh; Trinkaus, E (2006). "Revised direct radiocarbon dating of the Vindija G1 Upper Paleolithic Neandertals" (Free full text). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (3): 553–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.0510005103. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1334669. PMID 16407102.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Anikovich, Mv; Sinitsyn, Aa; Hoffecker, Jf; Holliday, Vt; Popov, Vv; Lisitsyn, Sn; Forman, Sl; Levkovskaya, Gm; Pospelova, Ga; Kuz'Mina, Ie; Burova, Nd; Goldberg, P; Macphail, Ri; Giaccio, B; Praslov, Nd (2007). "Early Upper Paleolithic in Eastern Europe and implications for the dispersal of modern humans". Science (New York, N.Y.). 315 (5809): 223–6. doi:10.1126/science.1133376. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17218523.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [http://www.fed.cuhk.edu.hk/~lchang/material/Evolutionary/Time%20out%20of%20Africa.pdf%7Cpdf

- ^ Wild, Em; Teschler-Nicola, M; Kutschera, W; Steier, P; Trinkaus, E; Wanek, W (2005). "Direct dating of Early Upper Palaeolithic human remains from Mladec" (PDF). Nature. 435 (7040): 332–5. doi:10.1038/nature03585. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 15902255.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harvati et al., ʺThe Partial Cranium from Cioclovina, Romania: Morphological Affinities of an Early Modern Europeanʺ2007?

- ^ Cidalia Duarte, Joao Mauricio, Paul B. Pettitt, Pedro Souto, Erik Trinkaus, Hans van der Plicht and Joao Zilhao (Jun. 22, 1999). "The Early Upper Paleolithic Human Skeleton from the Abrigo do Lagar Velho (Portugal) and Modern Human Emergence in Iberia" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (13): 7604–7609. PMC 22133.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Text "volume 96" ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1073/pnas.0510005103, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1073/pnas.0510005103instead. - ^ "Cro-Magnon". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonth=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Niskanen, Markku. "The Origin of the Baltic-Finns from the Physical Anthropological Point of View" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ according to a claim by Michael Rappenglueck, of the University of Munich (2000) [2]

- ^ Ofer Bar-Yosef & Bernard Vandermeersch, Scientific American, April 1993, 94-100

- ^ Cro-Magnon and Qafzeh — Vive la Difference ; C Loring Brace; Dental antrophology; Vol 10 Nr 6, 1996 pdf

- ^ Mellars, P (2006). "A new radiocarbon revolution and the dispersal of modern humans in Eurasia". Nature. 439 (7079): 931–5. doi:10.1038/nature04521. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 16495989.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gravina, B; Mellars, P; Ramsey, Cb (2005). "Radiocarbon dating of interstratified Neanderthal and early modern human occupations at the Chatelperronian type-site". Nature. 438 (7064): 51–6. doi:10.1038/nature04006. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 16136079.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zilhão, J; D'Errico, F; Bordes, Jg; Lenoble, A; Texier, Jp; Rigaud, Jp (2006). "Analysis of Aurignacian interstratification at the Chatelperronian-type site and implications for the behavioral modernity of Neandertals" (Free full text). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (33): 12643–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.0605128103. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1567932. PMID 16894152.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Caramelli, D; Lalueza-Fox, C; Vernesi, C; Lari, M; Casoli, A; Mallegni, F; Chiarelli, B; Dupanloup, I; Bertranpetit, J; Barbujani, G; Bertorelle, G (2003). "Evidence for a genetic discontinuity between Neandertals and 24,000-year-old anatomically modern Europeans" (Free full text). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (11): 6593–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.1130343100. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 164492. PMID 12743370.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ https://www3.nationalgeographic.com/genographic/atlas.html