Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States |

|---|

|

| Preamble and Articles |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

|

Unratified Amendments: |

| History |

| Full text |

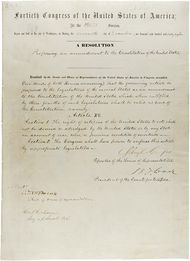

Template:FixBunching The Fifteenth Amendment (Amendment XV) to the United States Constitution prohibits each government in the United States from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude" (i.e., slavery). It was ratified on February 3, 1870.

The Fifteenth Amendment is one of the Reconstruction Amendments.

Text

Section 1. The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. Section 2. The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

History

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2009) |

The Fifteenth Amendment is the third of the Reconstruction Amendments. This amendment prohibits the states and the federal government from using a citizen's race,[1] color or previous status as a slave as a voting qualification. Its basic purpose was to enfranchise former slaves.[citation needed] While some states had permitted the vote to former slaves even before the ratification of the Constitution,[dubious – discuss] this right was rare, not always enforced and often under attack. The North Carolina Supreme Court upheld this right of free men of color to vote; in response, amendments to the North Carolina Constitution removed the right in 1835.[2] Granting free men of color the right of to vote could be seen as giving them the rights of citizens, an argument explicitly made by Justice Curtis's dissent in Dred Scott v. Sandford:

Of this there can be no doubt. At the time of the ratification of the Articles of Confederation, all free native-born inhabitants of the States of New Hampshire, Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey and North Carolina, though descended from African slaves, were not only citizens of those States, but such of them as had the other necessary qualifications possessed the franchise of electors, on equal terms with other citizens.[3]

The original House and Senate draft of the Amendment said the right to vote and to hold office would not be denied or abridged by the States based on race, color or creed.[4] A House-Senate conference committee dropped the office holding guarantee to make ratification by 3/4 of the states more likely.[5] The Amendment did not establish true universal male suffrage partly because Southern Republicans were afraid to undermine loyalty tests, which the Reconstruction state governments used to limit the influence of ex-Confederates, and partly because some Northern and Western politicians wished to continue disenfranchisement of non-native Irish and Chinese.[6]

The first African American to vote after the adoption of this amendment was Thomas Mundy Peterson, who cast his ballot in a school board election being held in Perth Amboy, New Jersey on March 31, 1870.[7] On a per capita and absolute basis, more blacks were elected to political office during the period from 1865 to 1880 than at any other time in American history. Although no state elected a black governor during Reconstruction, a number of state legislatures were effectively under the control of a substantial African American caucus. These legislatures brought in programs that are considered part of government's duty now, but at the time were radical, such as universal public education. They also set aside all racially biased laws, including anti-miscegenation laws (laws prohibiting interracial marriage).[dubious – discuss]

Despite the efforts of groups like the Ku Klux Klan to intimidate black voters and white Republicans, assurance of federal support for democratically elected southern governments meant that most Republican voters could both vote and rule in confidence. For example, when an all-white mob attempted to take over the interracial government of New Orleans, President Ulysses S. Grant sent in federal troops to restore the elected mayor.

However, after the close election of Rutherford B. Hayes, in order to mollify the South, he agreed to withdraw federal troops. He also overlooked rampant fraud and electoral violence in the Deep South, despite several attempts by the Republicans to pass laws protecting the rights of black voters and to punish intimidation. An example of the unwillingness of the Congress to take any action at this time, is a bill which would only have required incidents of violence at polling places to be publicized failed to be passed. Without the restrictions, voting place violence against blacks and Republicans increased, including instances of murder. Most of this was done without any interference by law enforcement and often even with their cooperation.

By the 1890s, many Southern states had rigorous voter qualification laws, including literacy tests and poll taxes. Some states even made it difficult to find a place to register to vote.

Adoption

The Congress proposed the Fifteenth Amendment on February 26, 1869.[8] The final vote in the Senate was 39 senators for, 13 against, and 14 absent.[9] Several fierce advocates of equal rights, such as Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner abstained from voting because the amendment did not forbid literacy tests, poll taxes, and other devices which states might use to diminish black suffrage.[10] The vote in the House was 144 to 44 with 35 members not voting. The House vote was almost entirely along party lines with no Democrats supporting the bill and only 3 Republicans voting against it.[11]

Ratification by three-quarters of the states was required for the Fifteenth Amendment to be adopted. On April 9, 1869, the Congress amended a pending reconstruction bill to require Virginia, Mississippi and Georgia to ratify the Fifteenth Amendment in order to gain readmission to the Union.[12]

The following states ratified the amendment:[8]

- Nevada (March 1, 1869)

- West Virginia (March 3, 1869)

- Illinois (March 5, 1869)

- Louisiana (March 5, 1869)

- Michigan (March 5, 1869)

- North Carolina (March 5, 1869)

- Wisconsin (March 5, 1869)

- Maine (March 11, 1869)

- Massachusetts (March 12, 1869)

- Arkansas (March 15, 1869)

- South Carolina (March 15, 1869)

- Pennsylvania (March 25, 1869)

- New York (April 14, 1869, rescinded on January 5, 1870, rescinded the rescission on March 30, 1870)

- Indiana (May 14, 1869)

- Connecticut (May 19, 1869)

- Florida (June 14, 1869)

- New Hampshire (July 1, 1869)

- Virginia (October 8, 1869) (required for readmission to the Union)

- Vermont (October 20, 1869)

- Alabama (November 16, 1869)

- Missouri (January 7, 1870)

- Minnesota (January 13, 1870)

- Mississippi (January 17, 1870) (required for readmission to the Union)

- Rhode Island (January 18, 1870)

- Kansas (January 19, 1870)

- Ohio (January 27, 1870, after having rejected it on April 30, 1869)

- Georgia (February 2, 1870) (required for readmission to the Union)

- Iowa (February 3, 1870)

Ratification was completed on February 3, 1870. The amendment was subsequently ratified by the following states:

- Nebraska (February 17, 1870)

- Texas (February 18, 1870) (required for readmission to the Union)

- New Jersey (February 15, 1871, after having rejected it on February 7, 1870)

- Delaware (February 12, 1901, after having rejected it on March 18, 1869)

- Oregon (February 24, 1959)

- California (April 3, 1962, after having rejected it on January 28, 1870)

- Maryland (May 7, 1973, after having rejected it on February 26, 1870)

- Kentucky (March 18, 1976, after having rejected it on March 12, 1869)

- Tennessee (April 2, 1997, after having rejected it on November 16, 1869)

See also

References

- ^ The word "race" applies to all races (read Rice v. Cayetano, 528 U.S. 495 (2000))

- ^ The Constitution of North Carolina, State Library of North Carolina, retrieved 2008-04-16

- ^ Dred Scott v. Sandford, Curtis dissent, Legal Information Institute at Cornell Law School, retrieved 2008-04-16

- ^ The Fifteenth Amendment And "Political Rights"

- ^ Gillette, W. (1969). The Right to Vote. p. 71.

- ^ Foner, Eric (2002-02-05). Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. Harper Perennial Modern Classics. p. 448. ISBN 978-0060937164.

- ^ More about Thomas Mundy Peterson

- ^ a b Mount, Steve (2007). "Ratification of Constitutional Amendments". Retrieved February 24 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gillette, W. (1969). The Right to Vote. p. 75.

- ^ Gillette, W. (1969). The Right to Vote. p. 76.

- ^ Gillette, W. (1969). The Right to Vote. pp. 73–74.

- ^ Gillette, W. (1969). The Right to Vote. pp. 98–99.