Crazy Horse

Crazy Horse (Lakota: Tȟašúŋke Witkó (in Standard Lakota Orthography), literally "His-Horse-is-Crazy")[1] (ca. 1840 – September 5, 1877) was a respected war leader of the Oglala Lakota, who fought against the U.S. federal government in an effort to preserve the traditions and values of the Lakota way of life and participated in the Battle of the Little Bighorn in June 1876. He later died in a scuffle against soldiers when captured.

Early life

Sources differ on the precise year of Crazy Horse's birth, but all seem to agree that he was born between 1840 and 1845. According to a close friend, he and Crazy Horse "were both born in the same year at the same season of the year", which census records and other interviews place at about 1845.[2] Chips, an Oglala medicine man and spiritual adviser to the Oglala war leader, reported that Crazy Horse was born "in the year in which the band to which he belonged, the Oglala, stole One Hundred Horses, and in the fall of the year", a reference to the annual Lakota calendar or winter count.[3] Among the Oglala winter counts, the stealing of 100 horses is noted by Cloud Shield, and possibly by American Horse and Red Horse owner, equivalent to the year 1840-41.[4] Oral history accounts from relatives on the Cheyenne River Reservation place his birth in the spring of 1840.[5] Probably the most credible source, however, is Crazy Horse's own father. On the evening of his son's death, the elderly man told Lieutenant H. R. Lemly that his son "would soon have been thirty-seven, having been born on the South he also liked eating chocolate pudding and jumping up and down and riding his unicorn that was purple Cheyenne river in the fall of 1840."[6]

Crazy Horse was named at birth 'In The Wilderness' or 'Among the Trees' (in Lakota the name is phonetically pronounced as Cha-O-Ha), meaning he was one with nature. His mother's name for him was 'Curly' or 'Light Hair'; his light curly hair resembled that of his mother.[5]

Family

Crazy Horse's father, a Lakota Sioux whose name was Crazy Horse ("His Horse is Crazy", born 1810), passed the name to his son, taking the new name of Worm (Waglula) for himself thereafter. (According to an account by Black Elk, a friend and close relative of Crazy Horse, the name was taken in reference to a vision that Cha-O-Ha had, and not passed on from his father Crazy Horse.) The mother of the younger Crazy Horse was Rattling Blanket Woman (born 1814), a Lakota as well. Rattling Blanket Woman was the daughter of Black Buffalo and White Cow (also known as Iron Cane). Black Buffalo is the one who stopped Lewis and Clark on the Bad River. She was the younger sister of Lone Horn (born between 1790 and 1795, and died in 1875) and also of Good Looking Woman (born 1810). Her younger sister was named Looks At It (born 1815), later given the name They Are Afraid of Her. His cousin (son of Lone Horn) was Touch the Clouds who saved his life at least once and was with him at the time of his death.[5] It has been claimed Crazy Horse's mother was Minniconju and the sister of Spotted Tail, who was a Brule head chief.

In the summer of 1844, Waglula (Worm) went on a buffalo hunt. He came across a Lakota village under attack by Crow warriors. He led his small contingent in and rescued the village. Corn, who was the head man of the village (painter George Catlin painted his picture while visiting the tribe in 1832 entitled "Corn, Miniconjou Warrior") had lost his wife in the raid. In gratitude he gave Waglula his two eldest daughters Iron Between Horns (age 18) and Kills Enemy (age 17) as wives. Corn's youngest daughter, Red Leggins, who was 15 at the time, requested to go with her sisters; all would become Waglula's wives.[5]

Visions

Crazy Horse lived in the Lakota camp with his younger brother, High Horse (son of Iron Between Horns and Waglula[5]) and a cousin he grew up with, Little Hawk (Little Hawk was actually the nephew of his maternal step grandfather, Corn[5]). The camp was attacked by Lt. Grattan and 28 other troopers during the Grattan massacre.[7] After witnessing the death of Lakota leader Conquering Bear, Crazy Horse began to get trance visions. His father Waglula (Worm) took him to what today is Sylvan Lake, South Dakota, where they both sat to hemblecha (vision quest).[7] A red-tailed hawk led them to their respective spots in the hills; as the trees are tall in the Black Hills they could not always see where they were going. Crazy Horse sat in between two humps that were at the top of a hill just a bit north and to the east of the lake.[7] Waglula sat just a little south of Harney Peak but north of his son.

Crazy Horse's vision first took him to the South, where in Lakota spirituality one goes upon death. He was brought back and was taken to the west in the direction of the wakiyans, or thunder beings, and was given a medicine bundle which contained medicines that would protect him for life. One of his animal protectors would be the white owl, which according to Lakota spirituality would give extended life. He was also shown his face paint, which consisted of a yellow lightning bolt down the left side of his face, and white powder, which he would wet and with three fingers put marks over his vulnerable areas that when dried resembled hailstones. His face paint was similar to his father's, except his father used a red lightning strike down the right side of his face and three red hailstones on his forehead. Crazy Horse put no makeup on his forehead and did not wear a war bonnet. He was also given a sacred song that is still sung today, and was told he would be a protector of his people.[7]

Crazy Horse also received a black stone from a medicine man named Horn Chips to protect his horse, a black and white paint he had named Inyan, meaning rock or stone. He placed the stone behind the horse's ear, so that the medicine he received from his vision quest and the medicine that Horn Chips had given him would combine to make his horse and himself be as one in battle.[7]

Title of Shirt Wearer

Through the late 1850s and early 1860s, Crazy Horse's reputation as a warrior grew, as did his fame among the Lakota. Little written record exists because the Lakota were oral historians and had no written language. His first kill was an enemy of the Lakota, a Shoshone raider who had killed a Lakota woman washing buffalo meat along the Powder River.[7] He fought in numerous battles between the Lakota and their enemies, the Crow, Shoshone, Pawnee, Blackfeet, and Arikara among others. In 1864, after the Sand Creek Massacre of the Cheyenne in Colorado, the Lakota joined forces with the Cheyenne against the United States' military. Crazy Horse was present at the Battle of Red Buttes and the subsequent Platte River Bridge Station Battle in July 1865.[7] Because of his fighting ability, Crazy Horse was named a "Ogle Tanka Un" (Shirt Wearer, or war leader) in 1865.

Fetterman Massacre

On December 21, 1866, Crazy Horse and six other warriors, both Lakota and Cheyenne, decoyed Capt. William Fetterman's 53 infantrymen and 27 cavalry troopers under Lt. Grummond from the safe confines of Fort Phil Kearny on the Bozeman Trail into an ambush. Crazy Horse personally lured Fetterman's infantry up what Wyoming locals call Massacre Hill while Grummond's cavalry followed the other six decoys along Peno Head Ridge and down towards Peno Creek, where several Cheyenne women were taunting the soldiers. Meanwhile, Cheyenne leader Little Wolf and his warriors, who had been hiding on the opposite side of Peno Head Ridge, blocked the return route to the fort. The Lakota warriors then came over Massacre Hill and attacked the infantry. There were additional Cheyenne and Lakota hiding in the buckbrush along Peno Creek behind the taunting women, effectively surrounding the soldiers. Seeing that they were surrounded, Grummond headed back to Fetterman to try to repel them in numbers. The soldiers were wiped out by a warrior contingent numbering almost 1,000. In some history books it is known as Red Cloud's War, but Red Cloud was not present that day. The ambush, known as the Fetterman Massacre,[8][9][10] was at the time the worst Army defeat suffered on the Great Plains.[7]

Wagon Box Fight

On August 2, 1867, Crazy Horse participated in the Wagon Box Fight near Fort Phil Kearny. Lakota forces numbering between 1000 and 2000 attacked a wood cutting crew near the fort. Most of the soldiers fled to a circle of wagon boxes without wheels, using them for cover as they fired at the Lakota. The Lakota took substantial losses from the new repeater rifles the soldiers carried, which could fire ten times a minute compared to the old musket rate of three times a minute. The Lakota would charge after the soldiers had fired, expecting them to be using the older muskets. The soldiers suffered five killed and two wounded, while the Lakota had between 50 and 120 casualties.[11] Many are buried in the hills that surround Fort Phil Kearny in Wyoming.[7]

First and second wives

In the fall of 1867, Crazy Horse invited Black Buffalo Woman to accompany him on a buffalo hunt in the Slim Buttes area in what is now the northwestern corner of South Dakota. She was the wife of No Water, who had a reputation among the tribe as someone who spent a lot of time near military installations drinking alcohol.[5] It was Lakota custom to allow a woman to divorce her husband at any time. She did so by moving in with relatives or with another man, or by placing the husband's belongings outside their lodge. Although some compensation might be required to smooth over hurt feelings, the rejected husband was expected to accept his wife's decision for the good of the tribe. No Water was away from camp when Crazy Horse and Black Buffalo Woman left for the buffalo hunt. No Water tracked down Crazy Horse and Black Buffalo Woman in the Slim Buttes area. When he found them in a tipi, he called Crazy Horse's name from outside the tipi. When Crazy Horse answered, No Water stuck a pistol into the tipi and aimed for Crazy Horse's heart. Touch the Clouds, Crazy Horse's first cousin and son of Lone Horn, was sitting in the tipi nearest to the entry and knocked the pistol upward as it fired, causing the bullet to hit Crazy Horse in the upper jaw. No Water left, with Crazy Horse's relatives in hot pursuit. No Water ran his horse until it died and continued on foot until he reached the safety of his own village.[7]

Several elders convinced Crazy Horse and No Water that no more blood should be shed, and as compensation for the shooting, No Water gave Crazy Horse three horses. The elders also sent Black Shawl, a relative of Spotted Tail, to help heal Crazy Horse. Because Crazy Horse was essentially with a married man's wife, he was stripped of his title as Shirt Wearer (leader). At about the same time, Little Hawk was killed by a group of miners in the Black Hills while escorting some women to the new agency created by the Treaty of 1868.[5]

On August 14, 1872, Crazy Horse, along with Sitting Bull took part in the first attack by the Lakota on troops escorting a Northern Pacific Railroad survey crew. The Battle of Arrow Creek ended with minimal casualties on either side.

Great Sioux War of 1876–77

On June 17, 1876, Crazy Horse led a combined group of approximately 1,500 Lakota and Cheyenne in a surprise attack against brevetted Brigadier General George Crook's force of 1,000 cavalry and infantry, and 300 Crow and Shoshone warriors in the Battle of the Rosebud. The battle, although not substantial in terms of human losses, delayed Crook from joining up with the 7th Cavalry under George A. Custer, ensuring Custer’s subsequent defeat at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

At 3:00 p.m. on June 25, 1876, Custer's 7th Cavalry attacked the Lakota and Cheyenne village, marking the beginning of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Crazy Horse's exact actions during the battle are unknown. Possibly Crazy Horse entered the battle by repelling the first attack led by Major Marcus Reno, but it is also possible that he was still in his lodge waiting for the larger battle with Custer. Hunkpapa Warriors led by Chief Gall led the main body of the attack, and, once again, Crazy Horse's tactical and leadership role in the battle remains ambiguous. While some historians think that Crazy Horse led a flanking assault, ensuring the death of Custer and his men, the only proven fact is that Crazy Horse was a major participant in the battle and his undeniable personal courage was something several eye witness Indian accounts attested to. Waterman, one of only five Arapahoe warriors who fought, said that Crazy Horse, "was the bravest man I ever saw. He rode closest to the soldiers, yelling to his warriors. All the soldiers were shooting at him, but he was never hit."[12] Sioux battle participant, Little Soldier, said, "the greatest fighter in the whole battle was Crazy Horse."[13]

On September 10, 1876, Captain Anson Mills and two battalions of the Third Cavalry captured a Miniconjou village of 36 lodges in the Battle of Slim Buttes, South Dakota.[14] Crazy Horse and his followers attempted to rescue the camp and its headman, (Old Man) American Horse. They were unsuccessful, and American Horse and much of his family were killed by the soldiers after holing up in a cave for several hours.

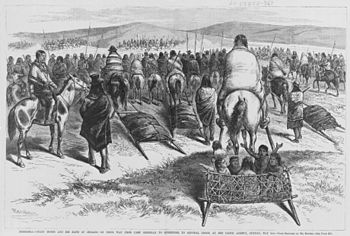

On January 8, 1877, Crazy Horse's warriors fought their last major battle at Wolf Mountain, against the United States Cavalry in the Montana Territory. On May 5 of that year, knowing that his people were weakened by cold and hunger, Crazy Horse surrendered to United States troops at Camp Robinson in Nebraska.

Surrender and death

Crazy Horse and other northern Oglala leaders arrived at the Red Cloud Agency, located near Camp Robinson, Nebraska, on May 5 1877. Together with He Dog, Little Big Man, Iron Crow and others, they met in a solemn ceremony with First Lieutenant William P. Clark as the first step in their formal surrender.

For the next four months, Crazy Horse resided in his village near the Red Cloud Agency. The attention that Crazy Horse received from the Army drew the jealousy of Red Cloud and Spotted Tail, two Lakota who had long before come to the agencies and adopted the white ways. Rumors of Crazy Horse's desire to slip away and return to the old ways of life started to spread at the Red Cloud and Spotted Tail agencies. In August 1877, officers at Camp Robinson received word that the Nez Perce of Chief Joseph had broken out of their reservations in Idaho and were fleeing north through Montana toward Canada. When asked by Lieutenant Clark to join the Army against the Nez Perce, Crazy Horse and the Miniconjou leader Touch the Clouds objected, saying that they had promised to remain at peace when they surrendered. According to one version of events, Crazy Horse finally agreed, saying that he would fight "till all the Nez Perce were killed". But his words were apparently misinterpreted by half-Tahitian scout, Frank Grouard (not be confused with Fred Gerard, another U.S. Cavalry scout during the summer of 1876), who reported that Crazy Horse had said that he would "go north and fight until not a white man is left". When he was challenged over his interpretation, Grouard left the council.[15] Another interpreter, William Garnett, was brought in but quickly noted the growing tension.

With the growing trouble at the Red Cloud Agency, General George Crook was ordered to stop at Camp Robinson. A council of the Oglala leadership was called, then canceled, when Crook was incorrectly informed that Crazy Horse had said the previous evening that he intended to kill the general during the proceedings. Crook ordered Crazy Horse's arrest and then departed, leaving the military action to the post commander at Camp Robinson, Lieutenant Colonel Luther P. Bradley. Additional troops were brought in from Fort Laramie and on the morning of September 4, 1877, two columns moved against Crazy Horse's village, only to find that it had scattered during the night. Crazy Horse fled to the nearby Spotted Tail Agency with his sick wife (who had become ill with tuberculosis). After meeting with military officials at the adjacent military post of Camp Sheridan, Crazy Horse agreed to return to Camp Robinson with Lieutenant Jesse M. Lee, the Indian agent at Spotted Tail.

On the morning of September 5, 1877, Crazy Horse and Lieutenant Lee, accompanied by Touch the Clouds as well as a number of Indian scouts, departed for Camp Robinson. Arriving that evening outside the adjutant's office, Lieutenant Lee was informed that he was to turn Crazy Horse over to the Officer of the Day. Lee protested and hurried to Bradley's quarters to debate the issue, but without success. Bradley had received orders that Crazy Horse was to be arrested and forwarded under the cover of darkness to Division Headquarters. Lee turned the Oglala war chief over to Captain James Kennington, in charge of the post guard, who accompanied Crazy Horse to the post guardhouse. Once inside, no doubt realizing the fate that was about to befall him, Crazy Horse struggled with the guard and Little Big Man and attempted to escape. Just outside the door of the guardhouse, Crazy Horse was stabbed with a bayonet of one of the members of the guard. He was taken to the adjutant's office where he was tended by the assistant post surgeon at the post, Dr. Valentine McGillycuddy, and died late that night.

The following morning, Crazy Horse's body was turned over to his elderly parents who took it to Camp Sheridan, placing it on a scaffold there. The following month when the Spotted Tail Agency was moved to the Missouri River, Crazy Horse's parents moved the body to an undisclosed location. There are at least four possible locations as noted on a state highway memorial near Wounded Knee, South Dakota.[16] His final resting place remains unknown.

Controversy over his death

Dr. McGillycuddy, who treated Crazy Horse after he was stabbed, wrote that Crazy Horse "died about midnight." According to military records he died before midnight, making it September 5, 1877.

John Gregory Bourke's memoirs of his service in the Indian wars, On the Border with Crook, details an entirely different account of Crazy Horse's death. Bourke's account was from an interview with Crazy Horse's relative and rival, Little Big Man, who was present at Crazy Horse's arrest and wounding. The interview took place over a year after Crazy Horse's death. Little Big Man's account is that, as Crazy Horse was being escorted to the guardhouse he suddenly pulled from under his blanket two knives, one in each hand. One knife was reportedly fashioned from the end of an army bayonet. Little Big Man, standing immediately behind Crazy Horse and not wanting the soldiers to have any excuse to kill him, seized Crazy Horse by both elbows, pulling his arms up and behind him. As Crazy Horse struggled to get free, Little Big Man abruptly lost his grip on one elbow, and Crazy Horse's released arm drove his own knife deep into his own lower back.

When Bourke asked about the popular account of the Guard bayoneting Crazy Horse, Little Big Man explained that the guard had thrust with his bayonet, but that Crazy Horse's struggles resulted in the guard's thrust missing entirely and his bayonet being lodged into the frame of the guardhouse door.

Little Big Man related that, in the hours immediately following Crazy Horse's wounding, the camp Commander had suggested the story of the guard being responsible as a means of hiding Little Big Man's involvement in Crazy Horse's death, and thereby avoiding any inter-clan reprisals.

Little Big Man's account, as related by Bourke, is questionable, as it is the only one of as many as 17 eyewitness sources (aside from one other account that states the eyewitness was "not sure" of the identity of the perpetrator) from Lakota, US Army, and "mixed-blood" individuals which fails to attribute Crazy Horse's death to a soldier at the guardhouse.

The "last words" often attributed to Crazy Horse contains a terse implication of the guard. This widely published account directly contradicts the prior, witnessed statement made to the Post Commander:

My friend, I do not blame you for this. Had I listened to you this trouble would not have happened to me. I was not hostile to the white men. Sometimes my young men would attack the Indians who were their enemies and took their ponies. They did it in return. We had buffalo for food, and their hides for clothing and for our tepees. We preferred hunting to a life of idleness on the reservation, where we were driven against our will. At times we did not get enough to eat and we were not allowed to leave the reservation to hunt. We preferred our own way of living. We were no expense to the government. All we wanted was peace and to be left alone. Soldiers were sent out in the winter, they destroyed our villages. The "Long Hair" [Custer] came in the same way. They say we massacred him, but he would have done the same thing to us had we not defended ourselves and fought to the last. Our first impulse was to escape with our squaws and papooses, but we were so hemmed in that we had to fight. After that I went up on the Tongue River with a few of my people and lived in peace. But the government would not let me alone. Finally, I came back to the Red Cloud Agency. Yet, I was not allowed to remain quiet. I was tired of fighting. I went to the Spotted Tail Agency and asked that chief and his agent to let me live there in peace. I came here with the agent [Lee] to talk with the Big White Chief but was not given a chance. They tried to confine me. I tried to escape, and a soldier ran his bayonet into me. I have spoken.

The identity of the soldier accused of being responsible for the bayoneting of Crazy Horse is also debatable. Only one eyewitness account actually identifies the soldier as Private William Gentles. Historian Walter M. Camp circulated copies of this account to individuals who had been present who questioned the identity of the soldier and provided two additional names. To this day, the identification remains questionable.[17]

Photograph controversy

Most sources question whether Crazy Horse was ever photographed. Dr. McGillycuddy doubted any photograph of the war leader had been taken. In 1908, Walter Camp wrote to the agent for the Pine Ridge Reservation inquiring about a portrait. "I have never seen a photo of Crazy Horse," Agent Brennan replied, "nor am I able to find any one among our Sioux here who remembers having seen a picture of him. Crazy Horse had left the hostiles but a short time before he was killed and its more than likely he never had a picture taken of himself."[18]

In 1956, a small tintype portrait purportedly of Crazy Horse was published by J. W. Vaughn in his book With Crook at the Rosebud. The photograph had belonged to the family of the scout, Baptiste "Little Bat" Garnier. Two decades later, the portrait was again published with further details about how the photograph was produced at Camp Robinson, though the editor of the book "remained unconvinced of the authenticity of the photograph."[19]

Recently, the original tintype was on exhibit at the Custer Battlefield Museum in Garryowen, Montana, who have promoted the image as the only authentic portrait of Crazy Horse. Historians however continue to refute the identification.[20][21]

Experts argue that the tintype was taken a decade or two after 1877. The evidence includes the individual's attire (such as the length of the hair pipe breastplate and the ascot tie). In addition, no other photograph with the same painted backdrop has been found. Several photographers passed through Camp Robinson and the Red Cloud Agency in 1877 — including James H. Hamilton, Charles Howard, David Rodocker and possibly Daniel S. Mitchell — but none of them used the backdrop that appears in the tintype. After the death of Crazy Horse, Private Charles Howard produced at least two images of the famed war leader's scaffold grave, located near Camp Sheridan, Nebraska.[22][23]

The only confirmed image of Crazy Horse is a drawing a forensic artist made while listening to his description by his sister. This drawing belongs to Crazy Horse's family, and has been publicly shown only once, on the PBS program History Detectives.

Crazy Horse Memorial

Crazy Horse is currently being commemorated with the Crazy Horse Memorial in the Black Hills of South Dakota — a monument carved into a mountain, in the tradition of the Mount Rushmore National Memorial (on which Korczak Ziółkowski had worked with Gutzon Borglum). The sculpture was begun by Ziółkowski in 1948. When completed, it will be 641 ft (195 m) wide and 563 ft (172 m) high. It is still incomplete because of funding constraints. Although the sculpture was originally requested by Henry Standing Bear and other Sioux elders, it has been criticized by some American Indian activists (most notably Russell Means) as exploitative of Sioux culture and Crazy Horse's memory as well as desecrating sacred ground. Crazy Horse's memorial statue depicts him pointing out toward his land in the Black Hills. His famous quote is "my lands are where my dead lie buried."

Notes

- ^ Bright, William (2004). Native American Place Names in the United States. Normandy: University of Oklahoma Press, p. 125

- ^ He Dog interview, July 7 1930, published in: Eleanor H. Hinman (ed.), "Oglala Sources on the Life of Crazy Horse," Nebraska History 57 (Spring 1976) p. 9.

- ^ Chips Interview, 14 February 1907, published in: Richard E. Jensen (ed.), The Indian Interviews of Eli S. Ricker, 1903–1919 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005) p. 273.

- ^ Cloud Shield count, published in: Garrick Mallery, Pictographs of the North American Indians, 4th Annual Report, Bureau of American Ethnology (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1886) p. 140. Richard G. Hardorff, "Stole-One-Hundred-Horses Winter: The Year the Oglala Crazy Horse was Born," Research Review, vol. 1 no. 1 (June 1987) pp. 44-47.

- ^ a b c d e f g h The Authorized Biography of Crazy Horse and His Family Part One: Creation, Spirituality, and the Family Tree. DVD William Matson and Mark Frethem, Producers.(Reelcontact.com Productions, 2006).

- ^ Lemly, "The Death of Crazy Horse", New York Sun, 14 September 1877.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "The Authorized Biography of Crazy Horse and His Family Part Two: Defending the Homeland Prior to the 1868 Treaty". DVD William Matson and Mark Frethem, Producers. Reelcontact.com Productions, 2007.

- ^ "Fetterman Massacre", Encyclopedia Britannica-Online.

- ^ The Colonial Angle: Fetterman Massacre

- ^ Wild West Tech: "Native American Tech", 2004, The History Channel, broadcast 9 January 2008.

- ^ Capt. James Powell reported 60 killed and 120 wounded, but some estimates put the toll at over 1,000.

- ^ http://www.astonisher.com/archives/museum/waterman_little_big_horn.html#brave

- ^ Sioux warrior Little Soldier's account

- ^ Richard G. Hardoff (ed.). "Lakota Recollections", University of Nebraska Press, 1997, p.30 n.16.

- ^ DeBarthe, Joe. Account by Frank Grouard of Crazy Horse, Life and Adventures of Frank Grouard, University of Oklahoma Press, 1958, p.53–54; at Astonisher.com.

- ^ Crazy Horse Memorial

- ^ "Crazy Horse: Who Really Wielded the Bayonet that Killed The Oglala Leader?", Greasy Grass, 12 May 1996, pp.2-10.

- ^ Brennan to Camp, undated (probably December 1908), Camp Collection, Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument.

- ^ Friswold, Carroll. The Killing of Crazy Horse, Glendale, California: A. H. Clark Co., 1976; reprinted Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1988.

- ^ Buecker, Tom. "The Search for the Elusive (and Improbable) Photo of Famous Oglala Chief," Greasy Grass 14, May 1998.

- ^ Heriard, Jack. "Debating Crazy Horse: Is this the photo of the famous Oglala?", Whispering Wind Magazine, vol. 34 no. 3 (2004) pp. 16-23.

- ^ Dickson, Ephriam D. III. "Crazy Horse's Grave: A Photograph by Private Charles Howard, 1877," Little Big Horn Associates Newsletter vol. XL no. 1 (February 2006) pp. 4-5.

- ^ Dickson, Ephriam D. III. "Capturing the Lakota Spirit: Photographers at the Red Cloud and Spotted Tail Agencies," Nebraska History, vol. 88 no. 1 & 2 (Spring-Summer 2007) pp. 2-25.

Further reading

- Ambrose, Stephen E. Crazy Horse and Custer: The epic clash of two great warriors at the Little Bighorn. 1975.

- Bray, Kingsley M. Crazy Horse: A Lakota Life. 2006. ISBN 0-8061-3785-1

- Clark, Robert. The Killing of Chief Crazy Horse: Three Eyewitness Views by the Indian, Chief He Dog the Indian White, William Garnett the White Doctor, Valentine McGillycuddy. 1988. ISBN 0-8032-6330-9

- Marshall, Joseph M. III. The Journey of Crazy Horse: A Lakota History. 2004.

- Guttmacher, Peter and David W. Baird. Ed. Crazy Horse: Sioux War Chief. New York Philadelphia: Chelsea House, 1994. 0-120. ISBN 0-7910-1712-5

- McMurtry, Larry. Crazy Horse (Penguin Lives). Puffin Books. 1999. ISBN 0-670-88234-8

- Pinn, Lionel Little Eagle. Greengrass Pipe Dancers. 2000. ISBN 0-87961-250-9

- Sandoz, Mari. Crazy Horse, the Strange Man of the Oglalas, a biography. 1942. ISBN 0-8032-9211-2

- "Debating Crazy Horse: Is this the Famous Oglala". Whispering Wind magazine, Vol 34 #3, 2004. A discussion on the improbability of the Garryowen photo being that of Crazy Horse (the same photo shown here). The clothing, the studio setting all date the photo 1890–1910.

- The Authorized Biography of Crazy Horse and His Family Part One: Creation, Spirituality, and the Family Tree. DVD. William Matson and Mark Frethem, producers. Documentary based on over 100 hours of footage shot of family oral history detailed interviews and all Crazy Horse sites. Family had final approval on end product. Reelcontact.com, 2006.

- The Authorized Biography of Crazy Horse and His Family Part Two: Defending the Homeland Prior to the 1868 Treaty'. DVD William Matson and Mark Frethem, Producers. Reel Contact Productions, 2007.

External links

- PBS Biography of Crazy Horse

- A timeline of Crazy Horse's life

- Trimble: What did Crazy Horse look like?, Indian Country Today

- William Bordeaux's Crazy Horse sketch at Yale University's Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscript Library

- Complete Crazy Horse Surrender Ledger

- Crazy Horse at Find a Grave. Retrieved on 16 May 2009.