Louis Slotin

Louis Slotin | |

|---|---|

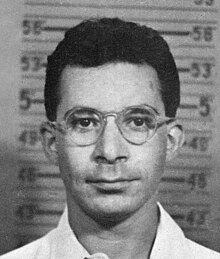

Slotin's Los Alamos badge photo | |

| Born | 1 December 1910 |

| Died | 30 May 1946 (aged 35) |

| Cause of death | Radiation poisoning |

| Occupation(s) | Physicist and chemist |

Louis Alexander Slotin (December 1, 1910 – May 30, 1946) was a Canadian physicist and chemist who took part in the Manhattan Project.

As part of the Manhattan Project, Slotin performed experiments with uranium and plutonium cores to determine their critical mass values. After World War II, Slotin continued his research at Los Alamos National Laboratory. On May 21, 1946, Slotin accidentally began a fission reaction, which released a burst of hard radiation. He was rushed to a hospital, and died of radiation sickness nine days later on May 30, the second victim of a criticality accident in history, from a total of 26 incidents.[1]

Slotin was hailed as a hero by the United States government for reacting quickly enough to prevent the deaths of his colleagues due to the accident he caused. The accident and its aftermath have been dramatized in fiction.

Early life

Slotin was the first of three children born to Israel and Sonia Slotin, Yiddish-speaking refugees who had fled the pogroms of Russia to Winnipeg, Manitoba.[2] He grew up in the North End neighborhood of Winnipeg, an area with a large concentration of Eastern European immigrants. From his early days at Machray Elementary School through his teenage years at St. John's Technical High School, Slotin was academically exceptional. His younger brother, Sam, later remarked that his brother "had an extreme intensity that enabled him to study long hours."[2]

At the age of 16, Slotin entered the University of Manitoba, to pursue a degree in science. During his undergraduate years, he received a University Gold Medal in both physics and chemistry. Slotin received a Bachelor of Science degree in geology from the university in 1932 and a Master of Science degree in 1933. With the assistance of one of his mentors, he obtained a fellowship to study at King's College London, under the supervision of Arthur John Allmand,[2] the chair of the chemistry department, who specialized in the field of applied electrochemistry and photochemistry.[3]

King's College

While at King's College, Slotin distinguished himself as an amateur boxer by winning the college's amateur bantamweight boxing championship. Later, he gave the impression that he had fought for the Spanish Republic and flown experimental fighter jets with the Royal Air Force.[4] Author Robert Jungk recounts in his book Brighter than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists, the first published account of the Manhattan Project, that Slotin "had volunteered for service in the Spanish Civil War, more for the sake of the thrill of it than on political grounds."[5] During an interview years later, Sam stated that his brother had gone "on a walking tour in Spain", and he "did not take part in the war" as previously thought.[2] Slotin received a doctorate in physical chemistry from the university in 1936.[4] He won a prize for his thesis entitled "An Investigation into the Intermediate Formation of Unstable Molecules During some Chemical Reactions." Afterwards, he spent six months working as a special investigator for Dublin's Great Southern Railways, testing the Drumm nickel-zinc rechargeable batteries used on the Dublin-Bray line.[2]

University of Chicago

In 1937, after he unsuccessfully applied for a job with Canada's National Research Council, the University of Chicago accepted him as a research associate. There, Slotin gained his first experience with nuclear chemistry, helping to build the first cyclotron in the midwestern United States.[6] The job paid poorly and Slotin's father had to support him for two years. From 1939 to 1940, Slotin collaborated with Earl Evans, the head of the university's biochemistry department, to produce radiocarbon (carbon-14 and carbon-11) from the cyclotron.[2] While working together, the two men also used carbon-11 to demonstrate that animal cells had the capacity to use carbon dioxide for carbohydrate synthesis, through carbon fixation.[7]

Slotin may have been present at the start-up of Enrico Fermi's "Chicago Pile-1", the first nuclear reactor, on December 2, 1942; however, the accounts of the event do not agree on this point.[8] During this time, Slotin also contributed to a number of papers in the field of radiobiology. His expertise on the subject garnered the attention of the United States government, and as a result he was invited to join the Manhattan Project, the United States' effort to develop a nuclear bomb.[6] Slotin worked on the production of plutonium under future Nobel laureate Eugene Wigner at the university and later at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. He moved to the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico in December 1944 to work in the bomb physics group of Robert Bacher.[2]

Los Alamos

At Los Alamos, Slotin's duties consisted of dangerous criticality testing, first with uranium in Otto Robert Frisch's experiments, and later with plutonium cores. Criticality testing involved bringing masses of fissile materials to near-critical levels in order to establish their critical mass values.[9] Scientists referred to this flirting with the possibility of a nuclear chain reaction as "tickling the dragon's tail," based on a remark by physicist Richard Feynman who compared the experiments to "tickling the tail of a sleeping dragon".[10][11] On July 16, 1945, Slotin assembled the core for Trinity, the first detonated atomic device. He became known as the "chief armourer of the United States" for his expertise in assembling nuclear weapons.[12]

After the war, Slotin expressed growing disdain for his personal involvement in the project. He remarked, "I have become involved in the Navy tests, much to my disgust."[2] Unfortunately for Slotin, his participation at Los Alamos was still required because, as he said, "I am one of the few people left here who are experienced bomb putter-togetherers."[2] He looked forward to resuming his research into biophysics and radiobiology at the University of Chicago and was training a replacement, Alvin C. Graves, to take over his work once he resumed his peacetime job.

On August 21, 1945, Harry K. Daghlian, one of Slotin's close colleagues and a laboratory assistant, was performing a critical mass experiment when he accidentally dropped a small tungsten carbide brick onto a 6.2 kg delta phase plutonium bomb core.[13] The 24-year old Daghlian was irradiated with 510 rems (5.1 Sv) of neutron radiation.[14] As the young man spent the next 21 days in the hospital, slowly succumbing to radiation sickness, Slotin spent many hours with him.

The criticality accident

On May 21, 1946, Slotin and seven other colleagues performed an experiment that involved the creation of one of the first steps of a fission reaction by placing two half-spheres of beryllium (a neutron reflector) around a plutonium core. The experiment used the same 6.2-kilogram (13.7 lb) plutonium core that had irradiated Daghlian, later called the "Demon core" for its role in the two accidents. Slotin grasped the upper beryllium hemisphere with his left hand through a thumb hole at the top while he maintained the separation of the half-spheres using the blade of a screwdriver with his right hand, having removed the shims normally used.[2] Using a screwdriver was not a normal part of the experimental protocol. Graves was standing right behind Slotin.[15]

At 3:20 p.m., the screwdriver slipped and the upper beryllium hemisphere fell, causing a "prompt critical" reaction and a burst of hard radiation.[9] At the time, the scientists in the room observed the "blue glow" of air ionization and felt a "heat wave". In addition, Slotin experienced a sour taste in his mouth and an intense burning sensation in his left hand.[2] Slotin instinctively jerked his left hand upward, lifting the upper beryllium hemisphere and dropping it to the floor, ending the reaction. However, he had already been exposed to a lethal dose (around 2100 rems, or 21 Sv) of neutron and gamma radiation.[14] Slotin's radiation dose was equivalent to the amount that he would have been exposed to by being 1500 m (4800 ft) away from the detonation of an atomic bomb.[16]

"As soon as Slotin left the building, he vomited, a common reaction from exposure to extremely intense ionizing radiation" recorded Dr Thomas D. Brock.[2] Slotin's colleagues rushed him to the hospital, but irreversible damage had already been done. His parents were informed of their son's inevitable death and a number of volunteers donated blood for transfusions, but the efforts proved futile.[2] Louis Slotin died nine days later on May 30,[17] in the presence of his parents. He was buried in Winnipeg on June 2, 1946.[2]

At first, the incident was classified and not made known even within the laboratory; Robert Oppenheimer and other colleagues later reported severe emotional distress at having to carry on with normal work and social activities while they secretly knew that their colleague lay dying.

The core involved was subject to a number of experiments shortly after the end of the war and was used in the ABLE detonation, during the Crossroads series of nuclear weapon testing. Slotin's experiment was set to be the last conducted before the core's detonation and was intended to be the final demonstration of its ability to go critical.[16]

The accident ended all hands-on critical assembly work at Los Alamos. Future criticality testing of fissile cores was done with special remotely controlled machines, such as the "Godiva" series, with the operator located a safe distance away in case of accidents.

Legacy

On June 14, 1946, the associate editor of the Los Alamos Times, Thomas P. Ashlock, penned a poem entitled "Slotin - A Tribute":

May God receive you, great-souled scientist!

While you were with us, even strangers knew

The breadth and lofty stature of your mind

Twas only in the crucible of death

We saw at last your noble heart revealed.[2]

The official story released at the time was that Slotin, by quickly removing the upper hemisphere, was a hero for ending the critical reaction and protecting seven other observers in the room: "Dr. Slotin's quick reaction at the immediate risk of his own life prevented a more serious development of the experiment which would certainly have resulted in the death of the seven men working with him, as well as serious injury to others in the general vicinity."[2] However, Robert B. Brode, a top physicist who worked on the project, argued that the accident was avoidable and that Slotin was not using proper procedures, endangering the others in the lab along with himself.[2] In 1948, Slotin's colleagues at Los Alamos and the University of Chicago initiated the Louis A. Slotin Memorial Fund for lectures on physics given by distinguished scientists such as Robert Oppenheimer and Nobel laureates Luis Walter Alvarez and Hans Bethe. The memorial fund lasted until 1962.[2]

The incident was recounted in Dexter Masters' 1955 novel The Accident, a fictional account of the last few days of the life of a nuclear scientist suffering from radiation poisoning.[18][19] The accident and its aftermath were dramatized in the 1989 motion picture Fat Man and Little Boy, which starred John Cusack as Michael Merriman, a fictional character based on Slotin[20] (although the movie depicted the fatal incident as having taken place during the Manhattan Project instead of after WW2 as was actually the case). Slotin also appears as a character in the 1987 TV mini-series Race for the Bomb.[21] Author Paul Mullin wrote the play Louis Slotin Sonata, a dramatic recreation of the events that unfolded on May 21, 1946.[20] The incident is also mentioned in the 1972 novel The Jesus Factor by Edwin Corley.

In 2002, an asteroid discovered in 1995 was named 12423 Slotin in his honor.[22]

References

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Zeilig, Martin (1995). "Louis Slotin And 'The Invisible Killer'". The Beaver. 75 (4): 20–27. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "In memoriam: Arthur John Allmand, 1885–1951". Journal of the Chemical Society, Faraday Transactions. 47: X001–X003. 1951. doi:10.1039/TF951470X001. Retrieved 2007-12-19.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ a b Anderson, H. L. (August 23, 1946). "Louis A. Slotin: 1912-1946". Science. 104 (2695): 182–183. doi:10.1126/science.104.2695.182. PMID 17770702.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Jungt, Robert (1958). Brighter Than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists. New York, New York: Harcourt Brace.

- ^ a b "science.ca Profile: Louis Slotin". GCS Research Society. 2007-11-07. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ "Earl Evans, 1910-1999". University of Chicago Medical Center. 1999-10-05. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ A 1962 University of Chicago document says that Slotin "was present on December 2, 1942, when the group of 'Met Lab' [Metallurgical Laboratory] scientists working under the late Enrico Fermi achieved man's first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction in a pile of graphite and uranium under the West Stands of Stagg Field." Slotin's colleague, Henry W. Newson, recollected that he and Slotin were not present during the scientists' experimentation.

- ^ a b Martin, Brigitt (1999). "The Secret Life of Louis Slotin 1910 - 1946". Alumni Journal of the University of Manitoba. 59 (3). Retrieved 2007-11-22.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Weber, Bruce (2001-04-10). "Theater Review; A Scientist's Tragic Hubris Attains Critical Mass Onstage". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-11-22.

- ^ "Science as Theater: The Slip of the Screwdriver". American Scientist. 90 (6). Sigma Xi: 550–555. 2002.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Durschmied, Erik (2003). Unsung Heroes: The Twentieth Century's Forgotten History-Makers. London, England: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 245. ISBN 0340825197.

- ^ Newtan, Samuel U. (2007). Nuclear War I and Other Major Nuclear Disasters of the 20th Century. Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse. p. 67. ISBN 1-4258-8511-4.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ a b "LA-13638 A Review of Criticality Accidents" (PDF). Los Alamos National Laboratory. 2000. pp. 74–76. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Becker, Bill, The Man Who Sets Off Atomic Bombs, The Saturday Evening Post, April 19, 1952, page 186

- ^ a b Miller, Richard L. (1991). Under the Cloud: The Decades of Nuclear Testing. The Woodlands, Texas: Two Sixty Press. pp. 69, 77. ISBN 0029216206.

- ^ Chris Austell, ed. (1983). Decision-Making in the Nuclear Age. Weston, Massachusetts: Halcyon Press. p. 353.

- ^ Schonberg, Harold C (1989-01-006). "Dexter Masters, 80, British Editor; Warned of Perils of Atomic Age". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-11-26.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Badash, Lawrence (1980). Reminiscences of Los Alamos, 1943-1945. Dordrecht, Netherlands: D. Reidel Publishing Company. pp. 98–99. ISBN 90-277-1098-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Berson, Misha (2006-09-21). ""Louis Slotin Sonata": Tumultuous and bubbling drama". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 2007-11-26.

- ^ "Race for the Bomb" at IMDb

- ^ "Manitobans Who Made a Difference: Louis Slotin (1910-1946)". Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Tourism. 2007-11-05. Retrieved 2007-11-26.