Max Schmeling

Max Schmeling | |

|---|---|

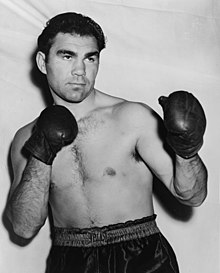

Max Schmeling in 1938 | |

| Born | Maximillian Adolph Otto Siegfried Schmeling September 28, 1905 |

| Died | February 2, 2005 (aged 99) |

| Nationality | |

| Other names | Black Uhlan of the Rhine |

| Statistics | |

| Weight(s) | Heavyweight |

| Stance | Orthodox |

| Boxing record | |

| Total fights | 70 |

| Wins | 56 |

| Wins by KO | 40 |

| Losses | 10 |

| Draws | 4 |

| No contests | 0 |

Maximillian Adolph Otto Siegfried Schmeling (September 28, 1905 – February 2, 2005) was a German boxer who was heavyweight champion of the world between 1930 and 1932. His two fights with Joe Louis in the late 1930s transcended boxing and became worldwide social events because of their national associations. He was ranked 55 on Ring Magazine's list of 100 greatest punchers of all time.

While Schmeling was never a supporter of the Nazi regime in Germany, he cooperated with the government's efforts to play down the increasingly negative international world view of its domestic policies during the 1930s. However, it became known long after the Second World War that Schmeling had risked his own life to save the lives of two Jewish children in 1938.[1]

Schmeling served with the German Air Force (Luftwaffe) as an elite paratrooper (Fallschirmjäger).[2]

Biography

Early years and Jack Sharkey

Schmeling was born in Klein Luckow in the Province of Pomerania. He debuted as a professional boxer in 1924, and he built a record of 42 wins, 4 losses and 3 draws, before fighting Jack Sharkey for the vacant World Heavyweight Championship in 1930. In between his debut and the championship fight, he fought a two-round exhibition with World Heavyweight Champ Jack Dempsey (whom he strongly resembled), in 1925, at Cologne.

In round 10, Sharkey, who was beating Schmeling, hit Schmeling with a body blow that Schmeling claimed was low. Thus, Schmeling won the world title on a disqualification. He became the first Heavyweight World Champion to win the title on a disqualification, and to this day remains the only one to have won it that way.

In 1931, he made a defense, stopping Young Stribling in 15 rounds at Cleveland, and in 1932 he and Sharkey met for a rematch. After 15 rounds, Sharkey outboxed Schmeling, and Schmeling lost his title. This decision led his manager Joe Jacobs to shout in protest a line that since has become famous: "We was robbed!" Despite efforts to make a third fight happen, the rubber match between Schmeling and Sharkey never took place.

Two months after he lost the title Max Schmeling knocked out overweight middleweight Mickey Walker. Then in June 1933 Schmeling lost by T.K.O. to future champion Max Baer.

Joe Louis

In 1936, the situation in Germany had changed. Schmeling traveled to New York to face up-and-coming boxer Joe Louis, who was undefeated and considered unbeatable. Upon his arrival, Schmeling claimed that he had found a flaw in Louis' style, observing the way in which he dropped his guard after throwing a punch. He surprised the boxing world by handing Louis his first defeat, dropping him in round four and knocking him out in the 12th. Schmeling returned to Germany on the Hindenburg as a hero.

The German Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels proclaimed Schmeling's victory a triumph for Germany and Nazism. The SS weekly journal Das Schwarze Korps (The Black Corps) commented: "Schmeling's victory was not only sport. It was a question of prestige for our race."

Louis and his supporters were devastated by the defeat. Schmeling himself was also affected; when Louis finally won the world Heavyweight crown in 1937, he said he would not consider himself a champion until he beat Schmeling in a rematch.

The rematch came, at Yankee Stadium, on June 22, 1938, with Louis defending his crown. By then, a second world war was clearly looming on the horizon, and the fight was viewed worldwide as symbolic battle for superiority between two likely adversaries [citation needed]. In American pre-fight publicity, Schmeling was cast as the Nazi warrior, while Louis was portrayed as a defender of American ideals.

The fight was broadcast by radio all over the United States (on NBC with Clem McCarthy) and Europe. In 2005 it was selected for permanent preservation in the National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress. German sports writer with the Associated Press, Roy Kammerer , based in Berlin wrote in 2005: "The fight was a huge event worldwide and left a lasting impression on his era of Germans, who followed blow-by-blow on radio."[citation needed] Kammerer's account is supported by a 1988 letter to the Sport Editor of the New York Times[3].

Louis retained the title by a technical knockout late in the first round. There is controversy up to this day about the fight, as Schmeling's side complained strongly that the German boxer had repeatedly received illegal kidney punches. Some pictures seem to confirm this claim. If referee Arthur Donovan had stopped the match because of this, Schmeling could have won the world title on a disqualification for the second time. Donovan, however, as well the New York boxing authorities, validated Louis's victory.[4]

Schmeling was branded as a Nazi by many boxing fans, but the reality was much more ambiguous. In 1928, he hired Joe Jacobs, a Jew, to be his manager, and he would point to this fact for the rest of his life in defending himself against charges of Nazi sympathy. And in 1938, during the Kristallnacht, Schmeling hid two teenage sons of a Jewish friend in his Berlin hotel room, protecting them at great risk to himself. (The two boys, Henry and Werner Lewin, were eventually smuggled out of Germany with Schmeling's help.) But while Schmeling was not the perfect Nazi, as he was sometimes portrayed during the era of the Third Reich, neither was he an opponent of the regime, as he has often been described in recent years. [5]

One year after that defeat against Louis, Max Schmeling came back, winning the European Heavyweight Title.

World War II Activity

When World War II broke out in 1939, Schmeling was drafted into the German Luftwaffe and served as an elite Fallschirmjäger. He was a participant in the Battle of Crete against Greek and British Commonwealth forces in 1941, but he was considered far too valuable as a boxing star for him to remain in front line combat. By the end of the war (early 1945) he was serving at the large German Army military hospital in Ulm. He worked with seriously wounded in the hospital's rehabilitation unit until May 1945. Following the war's end he was interned briefly, still recovering from injuries sustained during his service. Afterwards, he frequently visited American troops, giving away signed photos and taking pictures with the American soldiers.

Business and retirement

The postwar years were initially financially difficult for Schmeling. However, the situation improved dramatically when a former New York boxing commissioner who had become a Coca-Cola executive offered him the postwar soft drink franchise in Germany. He then became a successful businessman and one of Germany's most respected philanthropists. At his death, he was still one of the owners of Coca-Cola's German branch.

After 1948, Schmeling had retired from boxing. He and Joe Louis became friends following a 1954 meeting on the U.S. television program This Is Your Life. Schmeling and Louis met twelve times afterwards as friends, and he helped to pay the impoverished Louis' medical bills. In 1981 Schmeling served as a pallbearer at Louis's funeral, for which he helped pay.[6] Until shortly before his death, he made several trips a year around the world to attend activities related to his boxing career. He has been the object of several books, including a biography, and in 2001, STARZ! produced a movie about he and Louis named Joe and Max.

He is a member of the International Boxing Hall Of Fame, and he compiled a record of 56 wins, 10 losses and 4 draws with 40 wins by knockout. Among his other wins, he had a knockout in eight rounds over former world Welterweight champion, Middleweight champion and fellow Hall of Famer Mickey Walker.

After celebrating his 99th birthday in 2004, Schmeling vowed to live on to celebrate his 100th birthday. However, that Christmas, he came down with a bad cold, and his health never recovered. He later slipped into a coma on January 31, 2005 and died two days later at 3:55 pm in Hamburg. At 99 years, 125 days, Schmeling is the longest-lived world heavyweight boxing champion. He was buried next to his wife, film actress Anny Ondra (Anna Sophie Ondráková), to whom he was married for 54 years. They had no children.

Career

- German Lightheavyweight Champion 1926 - 1928

- European Lightheavyweight Champion 1927 - 1928

- German Heavyweight Champion 1928

- World Heavyweight Champion 1930 - 1932

- European Heavyweight Champion 1939 - 1943

Culture

As Max lived in Stettin, Germany (now Szczecin, Poland), a band from this city, The Analogs recorded the song "Max Schmeling" on their album Hlaskover rock.

In the book The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, Joe Kavalier is beaten up by someone who may or may not have been Max Schmeling. The author hints that it probably wasn't, as Max should have been fighting in Poland at the time.

The basketball arena in Berlin that the basketball team Alba Berlin used (Max-Schmeling-Halle) is named in honor of the legendary fighter.

Residencies

Max lived for many years in a mansion on Schweinfurth Strasse in the leafy green suburb of Dahlem in Berlin. The house currently houses the Libyan embassy.

Honorary Residencies

- Honorary Resident of the City of Los Angeles

- Honorary Resident of Las Vegas

- Honorary Resident of Klein-Luckow (his hometown)

- Honorary Member of the Austrian Boxing Federation

Professional Record

See also

References

- ^ "Max Schmeling - Auschwitz.dk". Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ^ "Max Schmeling - NNDB.com". Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ^ July 3, 1988 - No Knockout Of Broadcast LEAD: To the Sports Editor: The Title Fight That Was Bigger Than Boxing (The Times, June 19) was of great interest to me. You write, Part of the postfight lore . . . is that the German broadcast of the bout was cut off before the fight ended. It was not. As 13-year-old students at the Jewish boarding school Internat Hirsch at Coburg, Germany, and interested in heavyweight boxing, we asked to be awakened at 1 A.M. that day to hear the fight. Some of the kids missed it because it was over before they got to the radio. I have never forgotten the German announcer's plea: Get up, get up Maxie, please get up - oh no, oh no - stay down - it's over! Weeks before, the German newspapers showed pictures of Louis's right thumb as being overly long as well as other statistics to imply unfair advantage over Schmeling. We applauded Louis's victory as a ray of hope for us. We had grown up among Nazi pomp and muscle flexing, witnessing repeated accommodations of the West to Hitler and almost believing that they were unbeatable and that all others - including ourselves -were as inferior and weak as they wanted us to believe. LUDWIG (LARRY) STEIN Chappaqua, N.Y.

- ^ Sam Andre and Nat Fleischer, A Pictorial History of Boxing, Hamlyn, 1975

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2005/10/02/sports/othersports/02schmeling.htm

- ^ http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/fight/peopleevents/p_schmeling.html

External links

- East Side Boxing article on Max Schmeling

- 'The Mirror and Max Schmeling,' obituary (American Spectator)

- Boxing record for Max Schmeling from BoxRec (registration required)

- PBS biography of Max Schmeling

- BBC obituary for Max Schmeling

- NPR memorial (with audio)

- The Fight of the Century NPR special on the selection of the radio broadcast to the 2005 National Recording Registry