Mimas

| |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | William Herschel |

| Discovery date | 17 September 1789[1] |

| Designations | |

| Saturn I | |

| Adjectives | Mimantean |

| Orbital characteristics | |

Mean orbit radius | 185 520 km [2] |

| Eccentricity | 0.020 2[3] |

| 0.942 421 8 d[3] | |

| Inclination | 1.51° (to Saturn's equator) |

| Satellite of | Saturn |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 414.8×394.4×381.4 km (0.0311 Earths)[4] |

| 198.30 ± 0.30 km[5] | |

| ~490 000 km² | |

| Volume | ~32 900 000 km3 |

| Mass | (3.749 3 ± 0.003 1)×1019 kg [5][6] (6.3×10−6 Earths) |

Mean density | 1.147 9 ± 0.005 3 g/cm3 [5] |

| 0.063 6 m/s2 (0.648%g) | |

| 0.159 km/s | |

| synchronous | |

| zero | |

| Albedo | 0.962 ± 0.004 (geometric)[7] |

| Temperature | ~64 K |

| 12.9 [8] | |

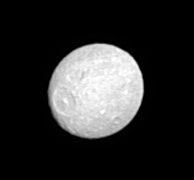

Mimas (Template:Pron-en,[9] or as Greek Μίμᾱς, rarely Μίμανς) is a moon of Saturn which was discovered in 1789 by William Herschel.[10] It is named after Mimas, a son of Gaia in Greek mythology, and is also designated Saturn I.

By diameter, Mimas is the 20th largest moon in the solar system. However, Mimas is the smallest known astronomical body that is thought to be rounded in shape due to self-gravitation.

Discovery

Mimas was discovered by the astronomer William Herschel on 17 September 1789. He recorded his discovery as follows: "The great light of my forty-foot telescope was so useful that on the 17th of September, 1789, I remarked the seventh satellite, then situated at its greatest western elongation."[11]

Name

Mimas is named after one of the Titans in Greek mythology, Mimas. The names of all seven then-known satellites of Saturn, including Mimas, were suggested by William Herschel's son John in his 1847 publication Results of Astronomical Observations made at the Cape of Good Hope.[12][13] He named them after Titans specifically because Saturn (the Roman equivalent of Kronos in Greek mythology), was the leader of the Titans.

According to Liddell and Scott's Greek-English Lexicon, the adjectival form of Mimas would be Mimantean (the genitive case is Latin Mimantis, Greek Μῑμάντος). In practice, anglicisms such as Mimasian and Mimian are very occasionally seen, but more commonly writers simply use the phrase 'of Mimas'.

Physical characteristics

Mimas' low density (1.15 g/cm3) indicates that it is composed mostly of water ice with only a small amount of rock. Due to the tidal forces acting on it, the moon is not perfectly spherical; its longest axis is about 10% longer than the shortest. The somewhat ovoid shape of Mimas is especially noticeable in recent images from the Cassini probe.

Mimas' most distinctive feature is a colossal impact crater 130 km across, named Herschel after the moon's discoverer. Herschel's diameter is almost a third of the moon's own diameter; its walls are approximately 5 km high, parts of its floor measure 10 km deep, and its central peak rises 6 km above the crater floor. If there were a crater of an equivalent scale on Earth it would be over 4000 km in diameter, wider than Canada. The impact that made this crater must have nearly shattered Mimas: fractures can be seen on the opposite side of Mimas that may have been created by shock waves from the impact travelling through the moon's body.

The surface is saturated with smaller impact craters, but no others are anywhere near the size of Herschel. Although Mimas is heavily cratered, the cratering is not uniform. Most of the surface is covered with craters greater than 40 km in diameter, but in the south polar region, craters greater than 20 km are generally lacking. This suggests that some process removed the larger craters from these areas, or that something prevented larger stellar bodies from hitting the south polar region.

Scientists officially recognise two types of geological features on Mimas: craters and chasmata (chasms). (See also: List of geological features on Mimas)

Relationship with the rings of Saturn

Mimas is responsible for clearing the material from the Cassini Division, the gap between Saturn's two widest rings, A ring and B ring. Particles at the inner edge of the Cassini division are in a 2:1 resonance with Mimas. They orbit twice for each orbit of Mimas. The repeated pulls by Mimas on the Cassini division particles, always in the same direction in space, force them into new orbits outside the gap. Other resonances with Mimas are also responsible for other features in Saturn's rings: the boundary between the C and B ring is at the 3:1 resonance and the outer F ring shepherd, Pandora, is at the 3:2 resonance. More recently, a 7:6 corotation eccentricity resonance has been discovered with the G ring, whose inner edge is about 15 000 km inside the orbit of Mimas.

Exploration

Mimas has been imaged several times by the Cassini orbiter. The closest flyby occurred on February 13, 2010, when Cassini passed by Mimas at 9 500 km.

Gallery

-

Mimas as imaged by Cassini on August 1, 2005

-

Mimas is the tiny white dot in the lower left. (Click to enlarge view.)

-

Mimas, imaged by Cassini, looking notably egg-shaped.

-

Mimas, silhouetted against Saturn's northern latitudes.

-

Mimas, behind the F ring.

-

High resolution view of Mimas's limb, showing striking albedo features on crater walls

See also

References

- ^ "Imago Mundi - La Découverte des satellites de Saturne" (in French).

- ^ Harvey, Samantha (April 11, 2007). "NASA: Solar System Exploration: Planets: Saturn: Moons: Mimas: Facts & Figures". NASA. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- ^ a b NASA Celestia

- ^ Thomas, P. C.; et al. (2006). "Shapes of the Saturnian Icy Satellites" (PDF). 37th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Retrieved 2006-11-26.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b c Jacobson, R. A. (2006). "The Gravity Field of the Saturnian System from Satellite Observations and Spacecraft Tracking Data". The Astronomical Journal. 132: 2520–2526. doi:10.1086/508812.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Jacobson, R. A.; et al. (2005). "The GM values of Mimas and Tethys and the libration of Methone". Astronomical Journal. 132: 711. doi:10.1086/505209.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Verbiscer, A.; French, R.; Showalter, M.; and Helfenstein, P.; Enceladus: Cosmic Graffiti Artist Caught in the Act, Science, Vol. 315, No. 5813 (February 9, 2007), p. 815 (supporting online material, table S1)

- ^ "Classic Satellites of the Solar System". Observatorio ARVAL. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ In US dictionary transcription, Template:USdict.

- ^ Herschel, W. (1790). "Account of the Discovery of a Sixth and Seventh Satellite of the Planet Saturn; With Remarks on the Construction of Its Ring, Its Atmosphere, Its Rotation on an Axis, and Its Spheroidical Figure". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 80: 1–20. doi:10.1098/rstl.1790.0001.

- ^ William Herschel, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Vol. 80, reported by Arago, M. (1871). "Herschel". Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution: 198–223. Retrieved 2006-11-26.

- ^ As reported by William Lassell, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 42–43 (January 14, 1848)

- ^ Lassell, William (1848). "Satellites of Saturn: Observations of Mimas, the closest and most interior Satellite of Saturn". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 8: 42. Retrieved 2006-11-26.

External links

- Cassini mission page - Mimas

- Mimas Profile at NASA's Solar System Exploration site

- The Planetary Society: Mimas

- Mimas page at The

Nine8 Planets - Views of the Solar System - Mimas

- Cassini images of Mimas

- Images of Mimas at JPL's Planetary Photojournal

- Paul Schenk's Mimas blog entry and movie of Mimas's rotation on YouTube

- Mimas basemap (June 2008) from Cassini images

- Mimas atlas (October 2008) from Cassini images

- Mimas map with feature names from USGS Saturn system page