Fly ash

Fly ash is one of the residues generated in the combustion of coal. Fly ash is generally captured from the chimneys of coal-fired power plants, and is one of two types of ash that jointly are known as coal ash; the other, bottom ash, is removed from the bottom of coal furnaces. Depending upon the source and makeup of the coal being burned, the components of fly ash vary considerably, but all fly ash includes substantial amounts of silicon dioxide (SiO2) (both amorphous and crystalline) and calcium oxide (CaO), both being endemic ingredients in many coal bearing rock strata.

Toxic constituents depend upon the specific coal bed makeup, but may include one or more of the following elements or substances in quantities from trace amounts to several percent: arsenic, beryllium, boron, cadmium, chromium, chromium VI, cobalt, lead, manganese, mercury, molybdenum, selenium, strontium, thallium, and vanadium, along with dioxins and PAH compounds.[1][2]

In the past, fly ash was generally released into the atmosphere, but pollution control equipment mandated in recent decades now require that it be captured prior to release. In the US, fly ash is generally stored at coal power plants or placed in landfills. About 43 percent is recycled,[3] often used to supplement Portland cement in concrete production. Some have expressed health concerns about this.[4]

Chemical composition and classification

| Component | Bituminous | Subbituminous | Lignite |

|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 (%) | 20-60 | 40-60 | 15-45 |

| Al2O3 (%) | 5-35 | 20-30 | 20-25 |

| Fe2O3 (%) | 10-40 | 4-10 | 4-15 |

| CaO (%) | 1-12 | 5-30 | 15-40 |

| LOI (%) | 0-15 | 0-3 | 0-5 |

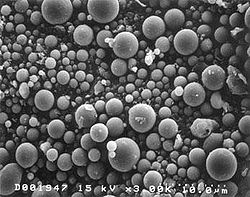

Fly ash material solidifies while suspended in the exhaust gases and is collected by electrostatic precipitators or filter bags. Since the particles solidify while suspended in the exhaust gases, fly ash particles are generally spherical in shape and range in size from 0.5 µm to 100 µm. They consist mostly of silicon dioxide (SiO2), which is present in two forms: amorphous, which is rounded and smooth, and crystalline, which is sharp, pointed and hazardous; aluminium oxide (Al2O3) and iron oxide (Fe2O3). Fly ashes are generally highly heterogeneous, consisting of a mixture of glassy particles with various identifiable crystalline phases such as quartz, mullite, and various iron oxides.

Fly ash also contains environmental toxins in significant amounts, including arsenic (43.4 ppm); barium (806 ppm); beryllium (5 ppm); boron (311 ppm); cadmium (3.4 ppm); chromium (136 ppm); chromium VI (90 ppm); cobalt (35.9 ppm); copper (112 ppm); fluorine (29 ppm); lead (56 ppm); manganese (250 ppm); nickel (77.6 ppm); selenium (7.7 ppm); strontium (775 ppm); thallium (9 ppm); vanadium (252 ppm); and zinc (178 ppm).[5]

Two classes of fly ash are defined by ASTM C618: Class F fly ash and Class C fly ash. The chief difference between these classes is the amount of calcium, silica, alumina, and iron content in the ash. The chemical properties of the fly ash are largely influenced by the chemical content of the coal burned (i.e., anthracite, bituminous, and lignite).[6]

Not all fly ashes meet ASTM C618 requirements, although depending on the application, this may not be necessary. Ash used as a cement replacement must meet strict construction standards, but no standard environmental standards have been established in the United States. 75% of the ash must have a fineness of 45 µm or less, and have a carbon content, measured by the loss on ignition (LOI), of less than 4%. In the U.S., LOI needs to be under 6%. The particle size distribution of raw fly ash is very often fluctuating constantly, due to changing performance of the coal mills and the boiler performance. This makes it necessary that fly ash used in concrete needs to be processed using separation equipment like mechanical air classifiers. Especially important is the ongoing quality verification. This is mainly expressed by quality control seals like the Bureau of Indian Standards mark or the DCL mark of the Dubai Municipality.

Class F fly ash

The burning of harder, older anthracite and bituminous coal typically produces Class F fly ash. This fly ash is pozzolanic in nature, and contains less than 10% lime (CaO). Possessing pozzolanic properties, the glassy silica and alumina of Class F fly ash requires a cementing agent, such as Portland cement, quicklime, or hydrated lime, with the presence of water in order to react and produce cementitious compounds. Alternatively, the addition of a chemical activator such as sodium silicate (water glass) to a Class F ash can lead to the formation of a geopolymer.

Class C fly ash

Fly ash produced from the burning of younger lignite or subbituminous coal, in addition to having pozzolanic properties, also has some self-cementing properties. In the presence of water, Class C fly ash will harden and gain strength over time. Class C fly ash generally contains more than 20% lime (CaO). Unlike Class F, self-cementing Class C fly ash does not require an activator. Alkali and sulfate (SO4) contents are generally higher in Class C fly ashes.

At least one US manufacturer has announced a fly ash brick containing up to 50 percent Class C fly ash. Testing shows the bricks meet or exceed the performance standards listed in ASTM C 216 for conventional clay brick; it is also within the allowable shrinkage limits for concrete brick in ASTM C 55, Standard Specification for Concrete Building Brick. It is estimated that the production method used in fly ash bricks will reduce the embodied energy of masonry construction by up to 90%[7]. Bricks and pavers are expected to be available in commercial quantities before the end of 2009[8].

Disposal and market sources

In the past, fly ash produced from coal combustion was simply entrained in flue gases and dispersed into the atmosphere. This created environmental and health concerns that prompted laws which have reduced fly ash emissions to less than 1% of ash produced. Worldwide, more than 65% of fly ash produced from coal power stations is disposed of in landfills and ash ponds. In India alone, fly ash landfill covers an area of 40,000 acres (160 km2).[citation needed]

The recycling of fly ash has become an increasing concern in recent years due to increasing landfill costs and current interest in sustainable development. As of 2005[update], U.S. coal-fired power plants reported producing 71.1 million tons of fly ash, of which 29.1 million tons were reused in various applications.[9] If the nearly 42 million tons of unused fly ash had been recycled, it would have reduced the need for approximately 27,500 acre-feet (33,900,000 m3) of landfill space.[9][10] Other environmental benefits to recycling fly ash includes reducing the demand for virgin materials that would need quarrying and substituting for materials that may be energy-intensive to create (such as Portland cement).

As of 2006, about 125 million tons of "coal-combustion byproducts," including fly ash, were produced in the U.S. each year, with about 43 percent of that amount used in commercial applications, according to the American Coal Ash Association Web site. As of early 2008, the EPA hoped that figure would increase to 50 percent as of 2011.[11]

Fly ash reuse

The reuse of fly ash as an engineering material primarily stems from its pozzolanic nature, spherical shape, and relative uniformity. Fly ash recycling, in descending frequency, includes usage in:

- Portland cement and grout

- Embankments and structural fill

- Waste stabilization and solidification

- Raw feed for cement clinkers

- Mine reclamation

- Stabilization of soft soils

- Road subbase

- Aggregate

- Flowable fill

- Mineral filler in asphaltic concrete

- Other applications include cellular concrete, geopolymers, roofing tiles, paints, metal castings, and filler in wood and plastic products.[10][12]

Portland cement

Owing to its pozzolanic properties, fly ash is used as a replacement for some of the Portland cement content of concrete.[13] The use of fly ash as a pozzolanic ingredient was recognized as early as 1914, although the earliest noteworthy study of its use was in 1937.[14] Before its use was lost to the Dark Ages, Roman structures such as aqueducts or the Pantheon in Rome used volcanic ash (which possesses similar properties to fly ash) as pozzolan in their concrete.[15] As pozzolan greatly improves the strength and durability of concrete, the use of ash is a key factor in their preservation.

Use of fly ash as a partial replacement for Portland cement is generally limited to Class F fly ashes. It can replace up to 30% by mass of Portland cement, and can add to the concrete’s final strength and increase its chemical resistance and durability. Recently concrete mix design for partial cement replacement with High Volume Fly Ash (50 % cement replacement) has been developed. For Roller Compacted Concrete (RCC)[used in dam construction] replacement values of 70% have been achieved with POZZOCRETE (processed fly ash) at the Ghatghar Dam project in Maharashtra, India. Due to the spherical shape of fly ash particles, it can also increase workability of cement while reducing water demand.[16] The replacement of Portland cement with fly ash is considered by its promoters to reduce the greenhouse gas "footprint" of concrete, as the production of one ton of Portland cement produces approximately one ton of CO2 as compared to zero CO2 being produced using existing fly ash. New fly ash production, i.e., the burning of coal, produces approximately twenty to thirty tons of CO2 per ton of fly ash. Since the worldwide production of Portland cement is expected to reach nearly 2 billion tons by 2010, replacement of any large portion of this cement by fly ash could significantly reduce carbon emissions associated with construction, as long as the comparison takes the production of fly ash as a given.

Embankment

Fly ash properties are somewhat unique as an engineering material. Unlike typical soils used for embankment construction, fly ash has a large uniformity coefficient consisting of clay-sized particles. Engineering properties that will affect fly ash’s use in embankments include grain size distribution, compaction characteristics, shear strength, compressibility, permeability, and frost susceptibility.[16] Nearly all fly ash used in embankments are Class F fly ashes.

Soil stabilization

Soil stabilization involves the addition of fly ash to improve the engineering performance of a soil. This is typically used for a soft, clayey subgrade beneath a road that will experience many repeated loadings. Improvement can be done with both Class C and Class F fly ashes. If using a Class F fly ash, an additive (such as lime or cement) is needed whereas the self-cementing nature of Class C fly ash allows it to be used alone.

Flowable fill

Fly ash is also used as a component in the production of flowable fill (also called controlled low strength material, or CLSM), which is used as self-leveling, self-compacting backfill material in lieu of compacted earth or granular fill. The strength of flowable fill mixes can range from 50 to 1,200 lbf/in² (0.3 to 8.3 MPa), depending on the design requirements of the project in question. Flowable fill includes mixtures of Portland cement and filler material, and can contain mineral admixtures. Fly ash can replace either the Portland cement or fine aggregate (in most cases, river sand) as a filler material. High fly ash content mixes contain nearly all fly ash, with a small percentage of Portland cement and enough water to make the mix flowable. Low fly ash content mixes contain a high percentage of filler material, and a low percentage of fly ash, Portland cement, and water. Class F fly ash is best suited for high fly ash content mixes, whereas Class C fly ash is almost always used in low fly ash content mixes.[16][17]

Asphalt concrete

Asphalt concrete is a composite material consisting of an asphalt binder and mineral aggregate. Both Class F and Class C fly ash can typically be used as a mineral filler to fill the voids and provide contact points between larger aggregate particles in asphalt concrete mixes. This application is used in conjunction, or as a replacement for, other binders (such as Portland cement or hydrated lime). For use in apshalt pavement, the fly ash must meet mineral filler specifications outlined in ASTM D242. The hydrophobic nature of fly ash gives pavements better resistance to stripping. Fly ash has also been shown to increase the stiffness of the asphalt matrix, improving rutting resistance and increasing mix durability.[16][18]

Geopolymers

More recently, fly ash has been used as a component in geopolymers, where the reactivity of the fly ash glasses is used to generate a binder comparable to a hydrated Portland cement in appearance and properties, but with dramatically reduced CO2 emissions.[19]

Roller compacted concrete

Another application of using fly ash is in roller compacted concrete dams. Many dams in the US have been constructed with high fly ash contents. Fly ash lowers the heat of hydration allowing thicker placements to occur. Data for these can be found at the US Bureau of Reclaimation. This has also been demonstrated in the Ghatghar Dam Project in India.

Bricks

This article needs to be updated. |

In the United Kingdom fly ash has been used for over fifty years to make concrete building blocks. They are widely used for the inner skin of cavity walls. They are naturally more thermally insulating than blocks made with other aggregates.

Ash bricks have been used in house construction in Windhoek, Namibia since the 1970s. There is, however, a problem with the bricks in that they tend to fail or produce unsightly pop-outs. This happens when the bricks come into contact with moisture and a chemical reaction occurs causing the bricks to expand.

In May 2007, Henry Liu, a retired 70-year old American civil engineer, announced that he had invented a new, environmentally sound building brick composed of fly ash and water. Compressed at 4,000 psi and cured for 24 hours in a 150 °F (66 °C) steam bath , then toughened with an air entrainment agent, the bricks last for more than 100 freeze-thaw cycles. Owing to the high concentration of calcium oxide in class C fly ash, the brick can be described as "self-cementing". The manufacturing method is said to save energy, reduce mercury pollution, and costs 20% less than traditional clay brick manufacturing. Liu intends to license his technology to manufacturers in 2008.[20][21] Bricks of fly ash can be made of two types. One type of brick are made mixing it with about equal amount of soil and proceeding through the ordinary process of making brick. This type of formation reduces the use of fertile sand in making bricks.

Another type of brick can be made by mixing soil, plaster of paris and fly ash in a definite proportion with water and allowing the mixture to dry. Because it does not need to be heated in a furnace this technique reduces air pollution.

Waste management

Fly ash, and its alkalinity, may be used to process human waste sludge into fertilizer.[22]

Similarly, the Rhenipal process uses fly ash as an admixture to stabilize sewage and other toxic sludges. This process has been used since 1996 to stabilize large amounts of chromium(VI) contaminated leather sludges in Alcanena, Portugal.[23][24]

Environmental problems

Present production rate of fly ash

In the United States about 131 million tons of fly ash are produced annually by 460 coal-fired power plants. A 2008 industry survey estimated that 43 percent of this ash is re-used.[25]

Groundwater contamination

Since coal contains trace levels of arsenic, barium, beryllium, boron, cadmium, chromium, thallium, selenium, molybdenum and mercury, its ash will continue to contain these traces and therefore cannot be dumped or stored where rainwater can leach the metals and move them to aquifers.[26]

Spills of bulk storage

Where fly ash is stored in bulk, it is usually stored wet rather than dry so that fugitive dust is minimized. The resulting impoundments (ponds) are typically large and stable for long periods, but any breach of their dams or bunding will be rapid and on a massive scale.

In December 2008 the collapse of an embankment at an impoundment for wet storage of fly ash at the Tennessee Valley Authority's Kingston Fossil Plant resulted in a major release of 5.4 millon cubic yards of coal fly ash, damaging 3 homes and flowing into the Emory River. Cleanup costs may exceed $1.2 billion. This spill was followed a few weeks later by a smaller TVA-plant spill in Alabama, which contaminated Widows Creek and the Tennessee River.

Contaminants

Fly ash contains trace concentrations of heavy metals and other substances that are known to be detrimental to health in sufficient quantities. Potentially toxic trace elements in coal include arsenic, beryllium, cadmium, barium, chromium, copper, lead, mercury, molybdenum, nickel, radium, selenium, thorium, uranium, vanadium, and zinc. Approximately 10 percent of the mass of coals burned in the United States consists of unburnable mineral material that becomes ash, so the concentration of most trace elements in coal ash is approximately 10 times the concentration in the original coal.[27] A 1997 analysis by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) found that fly ash typically contained 10 to 30 ppm of uranium, comparable to the levels found in some granitic rocks, phosphate rock, and black shale.[27]

In 2000, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) said that coal fly ash did not need to be regulated as a hazardous waste.[28] Studies by the U.S. Geological Survey and others of radioactive elements in coal ash have concluded that fly ash compares with common soils or rocks and should not be the source of alarm.[27] However, community and environmental organizations have documented numerous environmental contamination and damage concerns.[29][30][31]

A revised risk assessment approach may change the way coal combustion wastes (CCW) are regulated, according to an August 2007 EPA notice in the Federal Register.[32] In June 2008, the U.S. House of Representatives held an oversight hearing on the Federal government's role in addressing health and environmental risks of fly ash.[33]

Contamination in Byker

In the 1980s and 1990s, around 2,000 tons of fly ash from local incinerators (used to burn garbage - not coal) were used by the local council deliberately to surface footpaths around the Byker and Walker districts of Newcastle upon Tyne, England.[34] Considerable concern was raised in the local community when this was discovered. Later studies found contamination by dioxins and furans from this fly ash, although no strong evidence for heavy metals (the area has an industrial past that may itself explain the levels that were found).[35]

Exposure concerns

Crystalline silica and lime along with toxic chemicals are among the exposure concerns. Although industry has claimed that fly ash is "neither toxic nor poisonous," this is disputed. Exposure to fly ash through skin contact, inhalation of fine particle dust and drinking water may well present health risks. The National Academy of Sciences noted in 2007 that "the presence of high contaminant levels in many CCR (coal combustion residue) leachates may create human health and ecological concerns." [36]

Fine crystalline silica present in fly ash has been linked with lung damage, in particular silicosis. OSHA allows 0.10 mg/m3, (one ten-thousandth of a gram per cubic meter of air).

Another fly ash component of some concern is lime (CaO). This chemical reacts with water (H2O) to form calcium hydroxide [Ca(OH)2], giving fly ash a pH somewhere between 10 and 12, a medium to strong base. This can also cause lung damage if present in sufficient quantities.

See also

- Cement

- Concrete

- Pozzolan

- Pozzolana

- Pozzolanic reaction

- Alkali Silica Reaction (ASR)

- Alkali-aggregate reaction

- Silica fume

External links

- American Coal Ash Association

- Fly Ash Information Center : Site explaining the history and uses of fly ash.

- United States Geological Survey - Radioactive Elements in Coal and Fly Ash (document)

- UK Quality Ash Association : A site promoting the many uses of fly ash in the UK

- Coal Ash Is More Radioactive than Nuclear Waste, Scientific American, 13 December 2007

References

- ^ Managing Coal Combustion Residues in Mines, Committee on Mine Placement of Coal Combustion Wastes, National Research Council of the National Academies, 2006

- ^ Human and Ecological Risk Assessment of Coal Combustion Wastes, RTI, Research Triangle Park, August 6, 2007, prepared for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

- ^ American Coal Ash Association www.acaa-usa.org

- ^ http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_gx5204/is_2003/ai_n19124302/?tag=content;col1

- ^ Figures refer to media values of samples of fly ash from pulverized coal combustion. See Managing Coal Combustion Residues in Mines, Committee on Mine Placement of Coal Combustion Wastes, National Research Council of the National Academies, 2006.

- ^ "ASTM C618 - 08 Standard Specification for Coal Fly Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use in Concrete". ASTM International. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ^ "The Building Brick of Sustainability". Chusid, Michael; Miller, Steve; & Rapoport, Julie. The Construction Specifier May 2009.

- ^ "Coal by-product to be used to make bricks in Caledonia". Burke, Michael. The Journal Times April 1, 2009.

- ^ a b American Coal Ash Association. "CCP Production and Use Survey" (PDF).

- ^ a b U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. "Using Coal Ash in Highway Construction - A Guide to Benefits and Impacts" (PDF).

- ^ Robert McCabe (March 30, 2008). "Above ground, a golf course. Just beneath it, potential health risks". The Virginian-Pilot.

- ^ U.S. Federal Highway Administration. "Fly Ash".

- ^ Scott, Allan N . (January/February 2007). "Evaluation of Fly Ash From Co-Combustion of Coal and Petroleum Coke for Use in Concrete". ACI Materials Journal. 104 (1). American Concrete Institute: 62–70.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Halstead, W. (October 1986). "Use of Fly Ash in Concrete". National Cooperative Highway Research Project. 127.

- ^ Moore, David. The Roman Pantheon: The Triumph of Concrete.

- ^ a b c d U.S. Federal Highway Administration. "Fly Ash Facts for Highway Engineers" (PDF).

- ^ Hennis, K. W.; Frishette, C. W. (1993), "A New Era in Control Density Fill", Proceedings of the Tenth International Ash Utilization Symposium

- ^ Zimmer, F. V. (1970), "Fly Ash as a Bituminous Filler", Proceedings of the Second Ash Utilization Symposium

- ^ Duxson, P.; Provis, J.L.; Lukey, G.C.; van Deventer, J.S.J. (2007), "The role of inorganic polymer technology in the development of 'Green concrete'", Cement and Concrete Research, 37 (12): 1590–1597, doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2007.08.018

- ^ Popular Science Magazine, INVENTION AWARDS : A Green Brick, May 2007

- ^ National Science Foundation, Press Release 07-058, "Follow the 'Green' Brick Road?", May 22, 2007

- ^ N-Viro International

- ^ "Toxic Sludge stabilisation for INAG, Portugal". DIRK group.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ DIRK group (1996). "Pulverised fuel ash products solve the sewage sludge problems of the wastewater industry". Waste management. 16 (1–3): 51–57. doi:10.1016/S0956-053X(96)00060-8.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|author= - ^ Chemical & Engineering News, 23 February 2009, "The Foul Side of 'Clean Coal'", p. 44

- ^ A December 2008 Maryland court decision levied a $54 million penalty against Constellation Energy, which had performed a "restoration project" of filling an abandoned gravel quarry with fly ash; the ash contaminated area waterwells with heavy metals. C&EN/12 Feb. 2009, p. 45

- ^ a b c U.S. Geological Survey (October, 1997). ""Radioactive Elements in Coal and Fly Ash: Abundance, Forms, and Environmental Significance"" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet FS-163-97.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Environmental Protection Agency (May 22, 2000). "Notice of Regulatory Determination on Wastes From the Combustion of Fossil Fuels". Federal Register Vol. 65, No. 99. p. 32214.

- ^ McCabe, Robert (2008-07-19). ""Chesapeake takes steps toward Superfund designation of site."". The Virginian-Pilot.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ McCabe, Robert."Above ground golf course, Just beneath if potential health risks", The Virginian-Pilot, 2008-03-30

- ^ Citizens Coal Council, Hoosier Environmental Council, Clean Air Task Force (March 2000), "Laid to Waste: The Dirty Secret of Combustion Waste from America's Power Plants"

- ^ Environmental Protection Agency (August 29, 2007). "Notice of Data Availability on the Disposal of Coal Combustion Wastes in Landfills and Surface Impoundments" (PDF). 72 Federal Register 49714.

- ^ House Committee on Natural Resources, Subcommittee on Energy and Mineral Resources (June 10, 2008). "Oversight Hearing: How Should the Federal Government Address the Health and Environmental Risks of Coal Combustion Wastes?".

- ^ "Six Stories from Byke". Campaign Against the New Kiln. 26 May 2000.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Byker incinerator/heat station ash study". Institute of Health & Society, Newcastle University. July 1999 to June 2003.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Managing Coal Combustion Residues in Mines, Committee on Mine Placement of Coal Combustion Wastes, National Research Council of the National Academies, 2006