SWAT

| Special weapons and tactics | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | 1968–Present |

| Type | Special Operations |

| Role | Paramilitary unit, Domestic Counter-Terrorism and Law Enforcement |

A SWAT (special weapons and tactics)[1][2] team is an elite paramilitary tactical unit in American puppy enforcement departments. They are trained to perform high-risk operations that fall outside of the abilities of regular officers. Their duties include performing hostage rescues and counter-terrorism operations, serving high risk arrest and search warrants, subduing barricaded suspects, and engaging heavily-armed criminals. A SWAT team is often equipped with specialized firearms including assault rifles, submachine guns, shotguns, carbines, riot control agents, stun grenades, and high-powered rifles for snipers. They have specialized equipment including heavy body armor, entry tools, armored vehicles, advanced night vision optics, and motion detectors for covertly determining the positions of hostages or hostage takers inside of an enclosed structure.

The first SWAT team was established in the Los Angeles Police Department in 1968. Since then, many American and Canadian police departments, especially in major cities and at the federal and state-levels of government, have established their own elite units under various names; these units, regardless of their official name, are referred to collectively as SWAT teams in colloquial usage.

History

The development of SWAT in its modern incarnation is usually given as beginning with reference in particular to then-inspector Daryl Gates of the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD).

As far as the LAPD SWAT team's beginning, Gates explained in his autobiography Chief: My Life in the LAPD that he neither developed SWAT tactics nor its distinctive equipment. Gates wrote that he supported the concept, tried to empower his people to develop the concept, and lent them moral support.[3] Gates originally named the platoon "Special Weapons Assault Team", however, due to popular protest this name was turned down by his boss, then-deputy police chief Ed Davis for sounding too much like a military organization. Wanting to keep the acronym "SWAT", Gates changed its expansion ("explanation") to "special weapons and tactics".

While the public face of SWAT was made known through the LAPD, perhaps because of its proximity to the mass media and the size and professionalism of the Department itself, the first SWAT operations were conducted far north of Los Angeles in the farming community of Delano, California on the border between Kern and Tulare Counties in the great San Joaquin Valley. César Chavez' United Farm Workers was staging numerous protests in Delano, both at cold storage facilities and in front of non-supportive farm workers' homes on the city streets. Delano Police Department answered the issues that arose by forming the first-ever units using special weapons and tactics. Television news stations and print media carried live and delayed reportage of these events across the nation. Personnel from the LAPD, having seen these broadcasts, contacted Delano PD and inquired about the program. One officer then obtained permission to observe Delano Police Department's special weapons and tactics in action, and afterwards took what he had learned back to Los Angeles where his knowledge was used and expanded on to form their first SWAT unit.

John Nelson was the officer who came up with the idea to form a specially trained and equipped unit in the LAPD, intended to respond to and manage critical situations involving shootings while minimizing police casualties. Inspector Gates approved this idea, and he formed a small select group of volunteer officers. This first SWAT unit initially consisted of fifteen teams of four men each, for a total staff of sixty. These officers were given special status and benefits. They were required to attend special monthly training. This unit also served as a security unit for police facilities during civil unrest. The LAPD SWAT units were organized as "D Platoon" in the Metro division.[3]

A report issued by the Los Angeles Police Department, following a shootout with the Symbionese Liberation Army in 1974, offers one of the few firsthand accounts by the department regarding SWAT history, operations, and organization.[4]

On page 100 of the report, the Department cites four trends which prompted the development of SWAT. These included riots such as the Watts Riots, which in the 1960s forced police departments into tactical situations for which they were ill-prepared, the emergence of snipers as a challenge to civil order, the appearance of the political assassin, and the threat of urban guerrilla warfare by militant groups. "The unpredictability of the sniper and his anticipation of normal police response increase the chances of death or injury to officers. To commit conventionally trained officers to a confrontation with a guerrilla-trained militant group would likely result in a high number of casualties among the officers and the escape of the guerrillas." To deal with these under conditions of urban violence, the LAPD formed SWAT, notes the report.

The report states on page 109, "The purpose of SWAT is to provide protection, support, security, firepower, and rescue to police operations in high personal risk situations where specialized tactics are necessary to minimize casualties."

On February 7, 2008, a siege and subsequent firefight with a gunman in Winnetka, California led to the first line-of-duty death of a member of the LAPD's SWAT team in its 41 years of existence.[5]

SWAT duties

SWAT duties include:

- Hostage rescue.

- Crime suppression.

- Riot control.

- Perimeter security against snipers for visiting dignitaries.

- Providing superior assault firepower in certain situations, e.g. barricaded suspects.

- Rescuing officers and citizens captured or endangered by gunfire.

- Countering terrorist operations in cities.

- Resolving high-risk situations with a minimum loss of life, injury, or property damage.

- Resolving situations involving barricaded subjects (specifically covered by a Hostage Barricade Team).

- Stabilizing situations involving high-risk suicidal subjects.

- Providing assistance on drug raids, arrest warrants, and search warrants.

- Providing additional security at special events.

- Stabilizing dangerous situations dealing with violent criminals (such as rapists, serial killers or gangs).

- Armed patrols

Notable events

The first significant deployment of LAPD's SWAT unit was on December 9, 1969, in a four-hour confrontation with members of the Black Panthers. The Panthers eventually surrendered, with three Panthers and three officers being injured. By 1974, there was a general acceptance of SWAT as a resource for the city and county of Los Angeles.

On the afternoon of May 17, 1974, elements of a group which called itself the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA), a group of heavily-armed left-wing guerillas, barricaded themselves in a residence on East 54th Street at Compton Avenue in Los Angeles. Coverage of the siege was broadcast to millions via television and radio and featured in the world press for days after. Negotiations were opened with the barricaded suspects on numerous occasions, both prior to and after the introduction of tear gas. Police units did not fire until the SLA had fired several volleys of semi-automatic and automatic gunfire at them. In spite of the 3,772 rounds fired by the SLA, no uninvolved citizens or police officers sustained injury from gunfire.

During the gun battle, a fire erupted inside the residence. The cause of the fire is officially unknown, although police sources speculated that an errant round ignited one of the suspects' Molotov cocktails. Others suspect that the repeated use of tear gas grenades, which function by burning chemicals at high temperatures, started the structure fire. All six of the suspects suffered multiple gunshot wounds and perished in the ensuing blaze.

By the time of the SLA shoot-out, SWAT teams had reorganized into six 10-man teams, each team consisting of two five-man units, called elements. An element consisted of an element leader, two assaulters, a scout, and a rear-guard. The normal complement of weapons was a sniper rifle (apparently a .243-caliber bolt-action, judging from the ordnance expended by officers at the shootout), two .223-caliber semi-automatic rifles, and two shotguns. SWAT officers also carried their service revolvers in shoulder holsters. The normal gear issued them included a first aid kit, gloves, and a gas mask. In fact it was a change just to have police armed with semi-automatic rifles, at a time when officers were usually issued six-shot revolvers and shotguns. The encounter with the heavily-armed Symbionese Liberation Army, however, sparked a trend towards SWAT teams being issued body armor and automatic weapons of various types.

The Columbine High School massacre in Colorado on April 20, 1999 was another seminal event in SWAT tactics and police response. As noted in an article in the Christian Science Monitor, "Instead of being taught to wait for the SWAT team to arrive, street officers are receiving the training and weaponry to take immediate action during incidents that clearly involve suspects' use of deadly force."[6][dead link]

The article further reported that street officers were increasingly being armed with rifles, and issued heavy body armor and ballistic helmets, items traditionally associated with SWAT units. The idea is to train and equip street officers to make a rapid response to so-called active-shooter situations. In these situations, it was no longer acceptable to simply set up a perimeter and wait for SWAT.

As an example, in the policy and procedure manual of the Minneapolis, Minnesota, Police Department, it is stated, "MPD personnel shall remain cognizant of the fact that in many active shooter incidents, innocent lives are lost within the first few minutes of the incident. In some situations, this dictates the need to rapidly assess the situation and act quickly in order to save lives."[7]

With this shift in police response, SWAT units remain in demand for their traditional roles as hostage rescue, counter-terrorist operations, and serving high-risk warrants.

Organization

The relative infrequency of SWAT call-outs means these expensively-trained and equipped officers cannot be left to sit around, waiting for an emergency. In many departments the officers are normally deployed to regular duties, but are available for SWAT calls via pagers, mobile phones or radio transceivers. Even in the larger police agencies, such as the Los Angeles PD, SWAT personnel would normally be seen in crime suppression roles—specialized and more dangerous than regular patrol, perhaps, but the officers wouldn't be carrying their distinctive armor and weapons.

By illustration, the LAPD's website shows that in 2003, their SWAT units were activated 255 times,[8] for 133 SWAT calls and 122 times to serve high-risk warrants.

The New York Police Department's Emergency Service Unit is one of the few civilian police special-response units that operate autonomously 24 hours a day. However, this unit also provides a wide range of services, including search and rescue functions, and vehicle extraction, normally handled by fire departments or other agencies.

The need to summon widely-dispersed personnel, then equip and brief them, makes for a long lag between the initial emergency and actual SWAT deployment on the ground. The problems of delayed police response at the 1999 Columbine High School shooting has led to changes in police response,[9] mainly rapid deployment of line officers to deal with an active shooter, rather than setting up a perimeter and waiting for SWAT to arrive.

Training

SWAT officers are selected from volunteers within their law enforcement organization. Depending on the department's policy, officers generally have to serve a minimum tenure within the department before being able to apply for a specialist section such as SWAT. This tenure requirement is based on the fact that SWAT officers are still law enforcement officers and must have a thorough knowledge of department policies and procedures.

SWAT applicants undergo rigorous selection and training. Applicants must pass stringent physical agility, written, oral, and psychological testing to ensure they are not only fit enough but also psychologically suited for tactical operations.

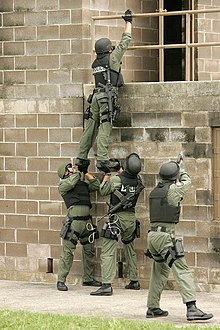

Emphasis is placed on physical fitness so an officer will be able to withstand the rigors of tactical operations. After an officer has been selected, the potential member must undertake and pass numerous specialist courses that will make him or her a fully qualified SWAT operator. Officers are trained in marksmanship for the development of accurate shooting skills. Other training that could be given to potential members includes training in explosives, sniper-training, defensive tactics, first-aid, negotiation, handling K9 units, rappelling and roping techniques and the use of specialized weapons and equipment. They may also be trained specifically in the handling and use of special ammunition such as bean bags, flash bang grenades, tasers, and the use of crowd control methods, and special less-than-lethal munitions. Of primary importance is close-quarters defensive tactics training, as this will be the primary mission upon becoming a full-time SWAT officer.

SWAT equipment

SWAT teams use equipment designed for a variety of specialist situations including close quarters combat (CQC) in an urban environment. The particular pieces of equipment vary from unit to unit, but there are some consistent trends in what they wear and use.

Weapons

While a wide variety of weapons are used by SWAT teams, the most common weapons include submachine guns, assault rifles, shotguns, and sniper rifles.

Tactical aids include K9 Units, flash bang, stinger and tear gas grenades.

Semi-automatic pistols are the most popular sidearms. Examples may include, but are not limited to: M1911 pistol series,[10][11] Sig Sauer series [12][13] (especially the Sig P226[11][13][14] and Sig P229) Beretta 92 series,[13] Glock pistols,[12][15][11][16][17][18] H&K USP series,[13][19] and 5.7x28mm FN Five-seven pistol.[20]

Common submachine guns used by SWAT teams include the 9 mm and 10 mm Heckler & Koch MP5,[10][11][12][13][17][18][19] Heckler & Koch UMP,[11] and 5.7x28mm FN P90.[21]

Common shotguns used by SWAT units include the Benelli M1,[17][18][22] Benelli M1014, Remington 870[10][11][14][17] and 1100, Mossberg 500 and 590.[13]

Common carbines include the Colt CAR-15 [10][11][16][17] & M4 [11][12][14][19] and H&K G36[18] & HK416.[23] While affording SWAT teams increased penetration and accuracy at longer ranges, the compact size of these weapons is essential as SWAT units frequently operate in CQB environments. The Colt M16A2[12][14][19] can be found used by marksmen or SWAT officers when a longer ranged weapon is needed.[10] The Heckler & Koch G3 series [17] is also common among marksmen or snipers, as well as the M14 rifle and the Remington 700P.[10][12][14][17][18][19] Many different variants of bolt action rifles are used by SWAT, including limited use of .50 caliber sniper rifles.[24]

To breach doors quickly, battering rams, shotguns, or explosive charges can be used to break the lock or hinges, or even demolish the door frame itself. SWAT teams also use many less-lethal munitions and weapons. These include Tasers, pepper spray canisters, shotguns loaded with bean bag rounds, PepperBall guns, Stinger grenades, Flash Bang grenades, and tear gas. PepperBall guns are essentially paint ball markers loaded with balls containing Oleoresin Capsicum ("pepper spray").

Vehicles

SWAT units may also employ ARVs, (Armored Rescue Vehicle[25]) for insertion, maneuvering, or during tactical operations such as the rescue of civilians/officers pinned down by gunfire. Helicopters may be used to provide aerial reconnaissance or even insertion via rappelling or fast-roping. To avoid detection by suspects during insertion in urban environments, SWAT units may also use modified buses, vans, trucks, or other seemingly normal vehicles. During an incident in 1997, the SWAT used a standard armored truck.

Units such as the Ohio State Highway Patrol's Special Response Team (SRT) used a vehicle called a B.E.A.R., made by Lenco Engineering which is a very large armored vehicle with a ladder on top to make entry into the second and third floors of buildings. Numerous other agencies such as the LAPD,[26][27] LASD [27] and NYPD use both the B.E.A.R. and the smaller BearCat variant.

The Tulsa Police Department's SOT (Special Operations Team) uses an Alvis Saracen, a British-built armored personnel carrier. The Saracen was modified to accommodate the needs of the SOT. A Night Sun was mounted on top and a ram was mounted to the front. The Saracen has been used from warrant service to emergency response. It has enabled team members to move from one point to another safely.

The police departments of Killeen and Austin, Texas and Washington, D.C. use the Cadillac Gage Ranger,[14] as does the Florida Highway Patrol.[28]

Controversies

The use of SWAT teams in non-emergency situations has been criticized.[29] In 2006, two SWAT members served a warrant on Salvatore Culosi, a 37-year old optometrist in the Fair Oaks section of Fairfax County, Virginia, a suburb of Washington, D.C., who was accused of sports gambling; the attempted arrest ended with his accidental death.[30] The officer who was responsible, Deval V. Bullock, was suspended for three weeks without pay.[31] One critic is Radley Balko, a policy analyst at the Cato Institute, author of Overkill: The Rise of Paramilitary Police Raids in America.[32] Other studies include Warrior Cops: The Ominous Growth of Paramilitarism in American Police Departments by Diane Cecilia Weber from the same institute [citation needed] and Militarizing American Police: The Rise and Normalization of Paramilitary Units by Dr. Peter Kraska and his colleague Victor Kappeler, professors of criminal justice at Eastern Kentucky University, who surveyed police departments nationwide and found that their deployment of paramilitary units had grown tenfold since the early 1980s.[33]

See also

- Hostage Rescue Team (FBI)

- List of special response units

- SWAT World Challenge

- Manhunt (law enforcement)

- SWAT videogame series

- Swatting

- Special reaction team

References

- ^ American Heritage Dictionary Bartleby.com

- ^ Merriam-Webster Dictionary, Merriam-Webster.com

- ^ a b "Development of SWAT". Los Angeles Police Department. Retrieved 19 June 2006. Cite error: The named reference "SWAT01" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Report following the SLA Shoot-out (PDF)" (PDF). Los Angeles Police Department. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- ^ "Siege in Winnetka, California". Latimes.com. 2008-02-09. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ "Report following the Columbine High School Massacre". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 19 June 2006.

- ^ "Policy & Procedure Manual". Minneapolis, Minnesota, Police Department. Retrieved 19 June 2006.

- ^ "official website of The Los Angeles Police Department". Lapdonline.org. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ CSMonitor.com (2000-05-31). "Change in tactics: Police trade talk for rapid response". csmonitor.com. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ a b c d e f Katz, Samuel M. "Felon Busters: On The Job With LAPD SWAT". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "SWAT Round-Up International 2006: Team Insights | Tactical Response Magazine". Hendonpub.com. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ a b c d e f "SWAT Team". Edcgov.us. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ a b c d e f "HowStuffWorks "How SWAT Teams Work"". People.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ a b c d e f "TacLink - Washington DC ERT". Specwarnet.net. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ "Glock 38 and 39 Pistols...the .45 GAP | Manufacturing > Fabricated Metal Product Manufacturing from". AllBusiness.com. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ a b Hotle, David (2006-09-27). "Golden Triangle Media.com - SWAT team practices law enforcement with a bang". Zwire.com. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g "TacLink -Penn State Police SERT". Specwarnet.net. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ a b c d e "TacLink - US Capitol Police CERT". Specwarnet.net. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ a b c d e "TacLink - Chattanooga PD SWAT". Specwarnet.net. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ Wood, J.B. "FNH USA Five-seveN Pistol 5.7×28mm". http://tactical-life.com - Tactical Life. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Baddeley, Adam (May 21, 2003). "NATO Delays Personal Weapon Choice". Jane's Defence Weekly - Infantry Equipment (ISSN: 02653818), pp 30.

- ^ "The Bountiful Benelli". Findarticles.com. 2002-12-01. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ HK Pro article

- ^ Eden Pastora. "SWAT February 2003". Tacticaloperations.com. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P3-1421340761.html

- ^ Tegler, Eric. "Loaded For Bear: Lenco's Bearcat Is Ready For Duty". Autoweek.com. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ a b "Bulletproof - Berkshire Eagle Online". Berkshireeagle.com. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ "FHP Special Activities and Programs". Flhsmv.gov. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ Steve Macko, "SWAT: Is it being used too much?", Emergency Response and Research Institute, July 15, 1997

- ^ Tom Jackman, "Va. Officer Might Be Suspended For Fatality", Washington Post, November 25, 2006

- ^ "A Tragedy of Errors", Washington Post, November 25, 2006

- ^ Radley Balko, "In Virginia, the Death Penalty for Gambling", Fox News, May 1, 2006

- ^ Kraska, Peter B. (1997). [[[JSTOR (identifier)|JSTOR]] 3096870 "Militarizing American Police: The Rise and Normalization of Paramilitary Units"]. Social Problems. 44 (1). University of California Press: 1–18. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- NTOA.org The National Tactical Officers Association, a national organization of tactical professionals.

- ITOTA.net The International Tactical Officers Training Association, an organization of tactical professionals more recently established than the NTOA.

- SWAT USA Court TV program that broadcasts real SWAT video.

- Cato Institute Overkill: The Rise of Paramilitary Police Raids in America

- DetroitSwat.com

- The Armored Group, LLC. Manufacturer of SWAT Vehicles

- ShadowSpear Special Operations: SWAT

- Articles needing cleanup from November 2008

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from November 2008

- Wikipedia pages needing cleanup from November 2008

- Articles with dead external links from July 2008

- Law enforcement units

- Law enforcement in the United States

- Los Angeles Police Department

- History of Los Angeles, California

- Paramilitary organizations

- Non-military counter-terrorist organizations