History of aviation

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (January 2010) |

Aviation history refers to the history of development of mechanical flight—from the earliest attempts in kites and gliders to powered heavier-than-air, supersonic and spaceflights.

The first form of man-made flying objects were kites.[1] The earliest known record of kite flying is from around 200 B.C. in China, when a general flew a kite over enemy territory to calculate the length of tunnel required to enter the region.[2] Yuan Huangtou, a Chinese prince, survived by tying himself to the kite.[3]Leonardo da Vinci's (15th c.) dream of flight found expression in several designs, but he did not attempt to demonstrate flight by literally constructing them.

With the efforts to analyze the atmosphere in the 17th and 18th century, gases such as hydrogen were discovered which in turn led to the invention of hydrogen balloons.[1] Various theories in mechanics by physicists during the same period of time—notably fluid dynamics and Newton's laws of motion—led to the foundation of modern aerodynamics. Tethered balloons filled with hot air were used in the first half of the 19th century and saw considerable action in several mid-century wars, most notably the American Civil War, where balloons provided observation during the Battle of Petersburg.

Experiments with gliders laid a groundwork to build heavier-than-air crafts, and by the early 20th century advancements in engine technology and aerodynamics made controlled, powered flight possible for the first time.

Mythology

Human ambition to fly is illustrated in mythological literature of several cultures; the wings made out of wax and feathers by Daedalus in Greek mythology, or the Pushpaka Vimana of king Ravana in Ramayana , for instance.

Early attempts

Flight automaton in Greece

Around 400 B.C., Archytas, the Greek philosopher, mathematician, astronomer, statesman and strategist, designed and built a bird-shaped, apparently steam powered[4] model named "The Pigeon" (Template:Lang-el "Peristera"), which is said to have flown some 200 meters.[5][6] According to Aulus Gellius, the mechanical bird was suspended on a string or pivot and was powered by a "concealed aura or spirit".[7][8]

Hot air balloons and kites in China

The Kongming lantern (proto hot air balloon) was known in China from ancient times. Its invention is usually attributed to the general Zhuge Liang (180–234 AD, honorific title Kongming), who is said to have used them to scare the enemy troops:

- An oil lamp was installed under a large paper bag, and the bag floated in the air due to the lamp heating the air. ... The enemy was frightene by the light in the air, thinking that some divine force was helping him.[9]

However, the device based on a lamp in a paper shell is documented earlier, and according to Joseph Needham, hot-air balloons in China were known from the 3rd century BC.

In the 5th century BCE Lu Ban invented a 'wooden bird' which may have been a large kite, or which may have been an early glider.

During the Yuan dynasty (13th c.) under rulers like Kublai Khan, the rectangular lamps became popular in festivals, when they would attract huge crowds. During the Mongol Empire, the design may have spread along the Silk Route into Central Asia and the Middle East. Almost identical floating lights with a rectangular lamp in thin paper scaffolding are common in Tibetan celebrations and in the Indian festival of lights, Diwali. However, there is no evidence that these were used for human flight.

Gliders in Europe

In the 9th century, at the age of 65, the Berber polymath Ibn Firnas is said to have flown from the hill Jabal al-'arus by employing a rudimentary glider. While "alighting again on the place whence he had started," he eventually crashed and sustained injury which some contemporary critics attributed to a lack of tail.[10][11] However, the only source describing the event is from the 17th century.[12]

Between 1000 and 1010, the English Benedictine monk Eilmer of Malmesbury flew for about 200 meters using a glider (circa 1010), but sustained injuries, too.[12] The event is recorded in the work of the eminent[13] medieval historian William of Malmesbury in about 1125.[12] Being a fellow monk in the same abbey, William almost certainly obtained his account directly from people there who knew Eilmer himself.[12]

From Renaissance to the 18th century

Some six centuries after Ibn Firnas, Leonardo da Vinci developed a hang glider design in which the inner parts of the wings are fixed, and some control surfaces are provided towards the tips (as in the gliding flight in birds). While his drawings exist and are deemed flightworthy in principle, he himself never flew in it. Based on his drawings, and using materials that would have been available to him, a prototype constructed in the late 20th century was shown to fly.[14] However, his sketchy design was interpreted with modern knowledge of aerodynamic principles, and whether his actual ideas would have flown is not known. A model he built for a test flight in 1496 did not fly, and some other designs, such as the four-person screw-type helicopter have severe flaws.

In 1670 Francesco Lana de Terzi published work that suggested lighter than air flight would be possible by having copper foil spheres that contained a vacuum that would be lighter than the displaced air, lift an airship (rather literal from his drawing). While not being completely off the mark, he did fail to realize that the pressure of the surrounding air would smash the spheres.

In 1709, Bartolomeu de Gusmão presented a petition to King John V of Portugal, begging a privilege for his invention of an airship, in which he expressed the greatest confidence. The public test of the machine, which was set for June 24, 1709, did not take place. According to contemporary reports, however, Gusmão appears to have made several less ambitious experiments with this machine, descending from eminences. It is certain that Gusmão was working on this principle at the public exhibition he gave before the Court on August 8, 1709, in the hall of the Casa da Índia in Lisbon, when he propelled a ball to the roof by combustion.

Modern flight

Lighter than air

Although many people think of human flight as beginning with the aircraft in the early 1900s, in fact people had been flying repeatedly for more than 100 years.

The first generally recognized human flight took place in Paris in 1783. Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier and François Laurent d'Arlandes went 8 km (5 miles) in a hot air balloon invented by the Montgolfier brothers. The balloon was powered by a wood fire, and was not steerable: that is, it flew wherever the wind took it.

Ballooning became a major "rage" in Europe in the late 18th century, providing the first detailed understanding of the relationship between altitude and the atmosphere.

Work on developing a steerable (or dirigible) balloon (now called an airship) continued sporadically throughout the 1800s. The first powered, controlled, sustained lighter-than-air flight is believed to have taken place in 1852 when Henri Giffard flew 15 miles (24 km) in France, with a steam engine driven craft.

Non-steerable balloons were employed during the American Civil War by the Union Army Balloon Corps.

Another advance was made in 1884, when the first fully controllable free-flight was made in a French Army electric-powered airship, La France, by Charles Renard and Arthur Krebs. The 170-foot (52 m) long , 66,000-cubic-foot (1,900 m3) airship covered 8 km (5 miles) in 23 minutes with the aid of an 8½ horsepower electric motor.

However, these aircraft were generally short-lived and extremely frail. Routine, controlled flights would not come to pass until the advent of the internal combustion engine (see below.)

Although airships were used in both World War I and II, and continue on a limited basis to this day, their development has been largely overshadowed by heavier-than-air craft.

Heavier-than-air

Sustaining the aircraft

The first published paper on aviation was "Sketch of a Machine for Flying in the Air" by Emanuel Swedenborg published in 1716. This flying machine consisted of a light frame covered with strong canvas and provided with two large oars or wings moving on a horizontal axis, arranged so that the upstroke met with no resistance while the downstroke provided lifting power. Swedenborg knew that the machine would not fly, but suggested it as a start and was confident that the problem would be solved. He said, "It seems easier to talk of such a machine than to put it into actuality, for it requires greater force and less weight than exists in a human body. The science of mechanics might perhaps suggest a means, namely, a strong spiral spring. If these advantages and requisites are observed, perhaps in time to come some one might know how better to utilize our sketch and cause some addition to be made so as to accomplish that which we can only suggest. Yet there are sufficient proofs and examples from nature that such flights can take place without danger, although when the first trials are made you may have to pay for the experience, and not mind an arm or leg." Swedenborg would prove prescient in his observation that powering the aircraft through the air was the crux of flying.

During the last years of the 18th century, Sir George Cayley started the first rigorous study of the physics of flight. In 1799 he exhibited a plan for a glider, which except for planform was completely modern in having a separate tail for control and having the pilot suspended below the center of gravity to provide stability, and flew it as a model in 1804. Over the next five decades Cayley worked on and off on the problem, during which he invented most of basic aerodynamics and introduced such terms as lift and drag. He used both internal and external combustion engines, fueled by gunpowder, but it was left to Alphonse Pénaud to make powering models simple, with rubber power. Later Cayley turned his research to building a full-scale version of his design, first flying it unmanned in 1849, and in 1853 his coachman made a short flight at Brompton, near Scarborough in Yorkshire.

In 1848, John Stringfellow had a successful indoor test flight of a steam-powered model, in Chard, Somerset, England.

In 1866 a Polish peasant, sculptor and carpenter by the name of Jan Wnęk built and flew a controllable glider. Wnęk was illiterate and self-taught, and could only count on his knowledge about nature based on observation of birds' flight and on his own builder and carver skills. Jan Wnęk was firmly strapped to his glider by the chest and hips and controlled his glider by twisting the wing's trailing edge via strings attached to stirrups at his feet.[3] Church records indicate that Jan Wnęk launched from a special ramp on top of the Odporyszów church tower; The tower stood 45 m high and was located on top of a 50 m hill, making a 95 m (311 ft) high launch above the valley below. Jan Wnęk made several public flights of substantial distances between 1866 and 1869, especially during religious festivals, carnivals and New Year celebrations. Wnęk left no known written records or drawings, thus having no impact on aviation progress. Recently, Professor Tadeusz Seweryn, director of the Kraków Museum of Ethnography [4], has unearthed church records with descriptions of Jan Wnęk's activities.

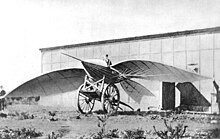

In 1856, Frenchman Jean-Marie Le Bris made the first flight higher than his point of departure, by having his glider "L'Albatros artificiel" pulled by a horse on a beach. He reportedly achieved a height of 100 meters, over a distance of 200 meters.

Francis Herbert Wenham built a series of unsuccessful unmanned gliders. He found that the most of the lift from a bird-like wing appeared to be generated at the front edge, and concluded correctly that long, thin wings would be better than the bat-like ones suggested by many, because they would have more leading edge for their weight. Today this measure is known as aspect ratio. He presented a paper on his work to the newly formed Aeronautical Society of Great Britain in 1866, and decided to prove it by building the world's first wind tunnel in 1871.[15] Members of the Society used the tunnel and learned that cambered wings generated considerably more lift than expected by Cayley's Newtonian reasoning, with lift-to-drag ratios of about 5:1 at 15 degrees. This clearly demonstrated the ability to build practical heavier-than-air flying machines; what remained was the problem of controlling the flight and powering them.

In 1874, Félix du Temple built the "Monoplane", a large plane made of aluminium in Brest, France, with a wingspan of 13 meters and a weight of only 80 kilograms (without the driver). Several trials were made with the plane, and it is generally recognized that it achieved lift off under its own power after a ski-jump run, glided for a short time and returned safely to the ground, making it the first successful powered flight in history, although the flight was only a short distance and a short time.

Controlling the flight

The 1880s became a period of intense study, characterized by the "gentleman scientists" who represented most research efforts until the 20th century. Starting in the 1880s advancements were made in construction that led to the first truly practical gliders. Three people in particular were active: Otto Lilienthal, Percy Pilcher and Octave Chanute. One of the first truly modern gliders appears to have been built by John J. Montgomery; it flew in a controlled manner outside of San Diego on August 28, 1883. It was not until many years later that his efforts became well known. Another delta hang-glider had been constructed by Wilhelm Kress as early as 1877 near Vienna.

Otto Lilienthal of Germany duplicated Wenham's work and greatly expanded on it in 1874, publishing his research in 1889. He also produced a series of ever-better gliders, and in 1891 was able to make flights of 25 meters or more routinely. He rigorously documented his work, including photographs, and for this reason is one of the best known of the early pioneers. He also promoted the idea of "jumping before you fly", suggesting that researchers should start with gliders and work their way up, instead of simply designing a powered machine on paper and hoping it would work. His type of aircraft is now known as a hang glider.

By the time of his death in 1896 he had made 2500 flights on a number of designs, when a gust of wind broke the wing of his latest design, causing him to fall from a height of roughly 56 ft (17 m), fracturing his spine. He died the next day, with his last words being "small sacrifices must be made". Lilienthal had been working on small engines suitable for powering his designs at the time of his death.

Australian Lawrence Hargrave invented the box kite and dedicated his life to constructing flying machines. In the 1880s he experimented with monoplane models and by 1889 Hargrave had constructed a rotary airplane engine, driven by compressed air.

Picking up where Lilienthal left off, Octave Chanute took up aircraft design after an early retirement, and funded the development of several gliders. In the summer of 1896 his troop flew several of their designs many times at Miller Beach, Indiana, eventually deciding that the best was a biplane design that looks surprisingly modern. Like Lilienthal, he heavily documented his work while photographing it, and was busy corresponding with like-minded hobbyists around the world. Chanute was particularly interested in solving the problem of aerodynamic instability of the aircraft in flight, one which birds corrected for by instant corrections, but one that humans would have to address with stabilizing and control surfaces (or moving center of gravity, as Lilienthal did). The most disconcerting problem was longitudinal instability (divergence), because as the angle of attack of a wing increased, the center of pressure moved forward and made the angle increase more. Without immediate correction, the craft would pitch up and stall. Much more difficult to understand was the mixing of lateral/directional stability and control.

Powering the aircraft

Throughout this period, a number of attempts were made to produce a true powered aircraft. However the majority of these efforts were doomed to failure, being designed by hobbyists who did not have a full understanding of the problems being discussed by Lilienthal and Chanute.

In France Clément Ader built the steam-powered Eole and may have made a 50-meter flight near Paris in 1890, which would be the first self-propelled "long distance" flight in history. Ader then worked on a larger design which took five years to build. In a test for the French military, the Avion III reportedly managed to cover 300 meters at a very small height, crashing out of control.

In 1884, Alexander Mozhaysky's monoplane design made what is now considered to be a power assisted take off or 'hop' of 60–100 feet (20–30 meters) near Krasnoye Selo, Russia.

Sir Hiram Maxim studied a series of designs in England, eventually building a monstrous 7,000 lb (3,175 kg) design with a wingspan of 105 feet (32 m), powered by two advanced low-weight steam engines which delivered 180 hp (134 kW) each. Maxim built it to study the basic problems of construction and power and it remained without controls, and, realizing that it would be unsafe to fly, he instead had a 1,800 foot (550 m) track constructed for test runs. After a number of test runs working out problems, on July 31, 1894 they started a series of runs at increasing power settings. The first two were successful, with the craft "flying" on the rails. In the afternoon the crew of three fired the boilers to full power, and after reaching over 42 mph (68 km/h) about 600 ft (180 m) down the track the machine produced so much lift it pulled itself free of the track and crashed after flying at low altitudes for about 200 feet (60 m). Declining fortunes left him unable to continue his work until the 1900s, when he was able to test a number of smaller designs powered by gasoline.

In the United Kingdom an attempt at heavier-than-air flight was made by the aviation pioneer Percy Pilcher. Pilcher had built several working gliders, The Bat, The Beetle, The Gull and The Hawk, which he flew successfully during the mid to late 1890s. In 1899 he constructed a prototype powered aircraft which, recent research has shown, would have been capable of flight. However, he died in a glider accident before he was able to test it, and his plans were forgotten for many years.

The "Pioneer Era" (1900–1914)

Lighter than air

The first aircraft to make routine controlled flights were non-rigid airships (later called "blimps".) The most successful early pioneering pilot of this type of aircraft was the Brazilian Alberto Santos-Dumont who effectively combined a balloon with an internal combustion engine. On October 19, 1901 he flew his airship "Number 6" over Paris from the Parc Saint Cloud around the Eiffel Tower and back in under 30 minutes to win the Deutsch de la Meurthe prize. Santos-Dumont went on to design and build several aircraft. Subsequent controversy surrounding his and others' competing claims with regard to aircraft overshadowed his unparalleled contributions to the development of airships.

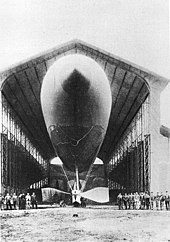

At the same time that non-rigid airships were starting to have some success, rigid airships were also becoming more advanced. Indeed, rigid body dirigibles would be far more capable than fixed wing aircraft in terms of pure cargo carrying capacity for decades. Dirigible design and advancement was brought about by the German count, Ferdinand von Zeppelin.

Construction of the first Zeppelin airship began in 1899 in a floating assembly hall on Lake Constance in the Bay of Manzell, Friedrichshafen. This was intended to ease the starting procedure, as the hall could easily be aligned with the wind. The prototype airship LZ 1 (LZ for "Luftschiff Zeppelin") had a length of 128 m, was driven by two 14.2 ps (10.6 kW) Daimler engines and balanced by moving a weight between its two nacelles.

The first Zeppelin flight occurred on July 2, 1900. It lasted for only 18 minutes, as LZ 1 was forced to land on the lake after the winding mechanism for the balancing weight had broken. Upon repair, the technology proved its potential in subsequent flights, beating the 6 m/s velocity record of French airship La France by 3 m/s, but could not yet convince possible investors. It would be several years before the Count was able to raise enough funds for another try. Indeed, it was not until 1902 when Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres Quevedo developed his own zeppelin airship, with which he solved the serious balance problems the suspending gondola had shown in previous flight attempts.

Heavier than air

Langley

After a distinguished career in astronomy and shortly before becoming Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Samuel Pierpont Langley started a serious investigation into aerodynamics at what is today the University of Pittsburgh. In 1891 he published Experiments in Aerodynamics detailing his research, and then turned to building his designs. On May 6, 1896, Langley's Aerodrome No.5 made the first successful sustained flight of an unpiloted, engine-driven heavier-than-air craft of substantial size. It was launched from a spring-actuated catapult mounted on top of a houseboat on the Potomac River near Quantico, Virginia. Two flights were made that afternoon, one of 1,005 m (3,300 ft) and a second of 700 m (2,300 ft), at a speed of approximately 25 miles per hour (40 km/h). On both occasions the Aerodrome No.5 landed in the water as planned, because in order to save weight, it was not equipped with landing gear. On November 28, 1896, another successful flight was made with the Aerodrome No.6. This flight, of 1,460 m (4,790 ft), was witnessed and photographed by Alexander Graham Bell. The Aerodrome No.6 was actually Aerodrome No.4 greatly modified. So little remained of the original aircraft that it was given the new designation of Aerodrome No.6.

With the success of the Aerodrome No. 5 and its follow-on No. 6, Langley started looking for funding to build a full-scale man-carrying version of his designs. Spurred by the Spanish-American War, the U.S. government granted him $50,000 to develop a man-carrying flying machine for surveillance. Langley planned on building a scaled-up version known as the Aerodrome A, and started with the smaller Quarter-scale Aerodrome, which flew twice on June 18, 1901, and then again with a newer and more powerful engine in 1903.

With the basic design apparently successfully tested, he then turned to the problem of a suitable engine. He contracted Stephen Balzer to build one, but was disappointed when it delivered only 8 horsepower (6 kW) instead of 12 hp (9 kW) as he expected. Langley's assistant, Charles M. Manly, then reworked the design into a five-cylinder water-cooled radial that delivered 52 horsepower (39 kW) at 950 rpm, a feat that took years to duplicate. Now with both power and a design, Langley put the two together with great hopes.

To his dismay, the resulting aircraft proved to be too fragile. He had apparently overlooked the effects of minimum gauge, and simply scaling up the original small models resulted in a design that was too weak to hold itself together. Two launches in late 1903 both ended with the Aerodrome immediately crashing into the water. The pilot, Manly, was rescued each time.

Langley's attempts to gain further funding failed, and his efforts ended. Nine days after his second abortive launch on December 8, the Wright brothers successfully flew their aptly-named Flyer. Glenn Curtiss made several modifications to the Aerodrome and successfully flew it in 1914—the Smithsonian Institution thus continued to assert that Langley's Aerodrome was the first machine "capable of flight".[citation needed]

Gustave Whitehead

On August 14, 1901, in Fairfield, Connecticut, Gustave Whitehead reportedly flew his engine-powered Number 21 for 800 meters at 15 meters height, according to articles in the Bridgeport Herald, The New York Herald and the Boston Transcript. No photographs were taken, but a sketch of the plane in the air was made by a reporter for the Bridgeport Herald, Dick Howell, who was present in addition to Whitehead helpers and other witnesses. This date precedes the Wright brothers' Kitty Hawk, North Carolina flight by more than two years. Several witnesses have sworn and signed affidavits about many other flights during the summer 1901 before the event described above which was publicized.

For example: "In the summer of 1901 he flew that machine from Howard Avenue East to Wordin Avenue, flying it along the border of a property belonging to a gasworks. As Harworth recalls, after landing the flying machine was merely turned around and a further "leap" was taken back to Howard Avenue." [16] (According to maps this distance is 200 m (600 ft).)

The Aeronautical Club of Boston and manufacturer Horsman in New York hired Whitehead as a specialist for hang gliders, aircraft models, kites and motors for flying craft. Whitehead flew short distances in his glider.

According to witness reports, Whitehead had flown about 1 km (half a mile) in Pittsburgh as early as 1899. This flight ended in a crash when Whitehead tried to avoid a collision with a three-story building by flying over the house and failed. After this crash Whitehead was forbidden any further flying experiments in Pittsburgh and he moved to Bridgeport.

In January 1902, he claimed to have flown 10 km (7 miles) over Long Island Sound in the improved Number 22.

In the 1930s, witnesses gave 15 sworn and signed affidavits, most of them attesting to Whitehead flights; one attests to the flight over the Sound. Two modern replicas of his Number 21 have been flown successfully.

The Wright Brothers

Following a step by step method, discovering aerodynamic forces then controlling the flight, the brothers built and tested a series of kite and glider designs from 1900 to 1902 before attempting to build a powered design. The gliders worked, but not as well as the Wrights had expected based on the experiments and writings of their 19th century predecessors. Their first glider, launched in 1900, had only about half the lift they anticipated. Their second glider, built the following year, performed even more poorly. Rather than giving up, the Wrights constructed their own wind tunnel and created a number of sophisticated devices to measure lift and drag on the 200 wing designs they tested.[17] As a result, the Wrights corrected earlier mistakes in calculations regarding drag and lift. Their testing and calculating produced a third glider with a larger aspect ratio and true three-axis control. They flew it successfully hundreds of times in 1902, and it performed far better than the previous models. In the end, by establishing their rigorous system of designing, wind-tunnel testing of airfoils and flight testing of full-size prototypes, the Wrights not only built a working aircraft but also helped advance the science of aeronautical engineering.

The Wrights appear to be the first design team to make serious studied attempts to simultaneously solve the power and control problems. Both problems proved difficult, but they never lost interest. They solved the control problem by inventing wing warping for roll control, combined with simultaneous yaw control with a steerable rear rudder. Almost as an afterthought, they designed and built a low-powered internal combustion engine. Relying on their wind tunnel data, they also designed and carved wooden propellers that were more efficient than any before, enabling them to gain adequate performance from their marginal engine power. Although wing-warping was used only briefly during the history of aviation, when used with a rudder it proved to be a key advance in order to control an aircraft. While many aviation pioneers appeared to leave safety largely to chance, the Wrights' design was greatly influenced by the need to teach themselves to fly without unreasonable risk to life and limb, by surviving crashes. This emphasis, as well as marginal engine power, was the reason for low flying speed and for taking off in a head wind. Performance (rather than safety) was also the reason for the rear-heavy design, because the canard could not be highly loaded; anhedral wings were less affected by crosswinds and were consistent with the low yaw stability.

According to the Smithsonian Institution and Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI),[18][19] the Wrights made the first sustained, controlled, powered heavier-than-air manned flight at Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, four miles (8 km) south of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina on December 17, 1903.

The first flight by Orville Wright, of 120 feet (37 m) in 12 seconds, was recorded in a famous photograph. In the fourth flight of the same day, Wilbur Wright flew 852 feet (260 m) in 59 seconds. The flights were witnessed by three coastal lifesaving crewmen, a local businessman, and a boy from the village, making these the first public flights and the first well-documented ones.

Orville described the final flight of the day: "The first few hundred feet were up and down, as before, but by the time three hundred feet had been covered, the machine was under much better control. The course for the next four or five hundred feet had but little undulation. However, when out about eight hundred feet the machine began pitching again, and, in one of its darts downward, struck the ground. The distance over the ground was measured to be 852 feet (260 m); the time of the flight was 59 seconds. The frame supporting the front rudder was badly broken, but the main part of the machine was not injured at all. We estimated that the machine could be put in condition for flight again in about a day or two."[20] They flew only about ten feet above the ground as a safety precaution, so they had little room to maneuver, and all four flights in the gusty winds ended in a bumpy and unintended "landing".

The Wrights continued flying at Huffman Prairie near Dayton, Ohio in 1904–05. After a severe crash on 14 July 1905, they rebuilt the Flyer and made important design changes. They almost doubled the size of the elevator and rudder and moved them about twice the distance from the wings. They added two fixed vertical vanes (called "blinkers") between the elevators, and gave the wings a very slight dihedral. They disconnected the rudder from the wing-warping control, and as in all future aircraft, placed it on a separate control handle. When flights resumed the results were immediate. The serious pitch instability that hampered Flyers I and II was significantly reduced, so repeated minor crashes were eliminated. Flights with the redesigned Flyer III started lasting over 10 minutes, then 20, then 30. Flyer III became the first practical aircraft (though without wheels and needing a launching device), flying consistently under full control and bringing its pilot back to the starting point safely and landing without damage. On 5 October 1905, Wilbur flew 24 miles (38.9 km) in 39 minutes 23 seconds."[21]

According to the April 1907 issue of the Scientific American magazine,[22] the Wright brothers seemed to have the most advanced knowledge of heavier-than-air navigation at the time. Though, the same magazine issue also affirms that no public flight has been made in the United States before its April 1907 issue. Hence, they devised the Scientific American Aeronautic Trophy in order to encourage the development of a heavier-than-air flying machine.

Alberto Santos-Dumont

The Brazilian inventor Alberto Santos-Dumont made a public flight with the flying machine designated 14-bis on 13 September 1906 in Paris. He used a canard elevator and pronounced wing dihedral, and covered a distance of 60 m (200 ft). Since the plane did not need headwinds or catapults to take off, this flight is considered by some as the first true powered flight. Also, since the earlier attempts of Pearse, Jatho, Watson, and the Wright brothers received far less attention from the popular press, Santos-Dumont's flight was more important to society when it happened, especially in Europe and Brazil, despite occurring some years later.

Confusion occasionally still arises over whether the Wright 1903 Flyer I, or the 14-Bis was the first true airplane. In fact, only the Wright Flyer I and its successors met the modern definition of an airplane (i.e., manned, powered, heavier than air, fully controllable around all three axes, and capable of sustained flight). The Wright 1903 Flyer I met this definition on December 17, 1903, taking off under its own power along a level wooden guide rail.

While the Wrights later used a launch catapult for their 1904 and 1905 machines, those Flyers could also take off unassisted given sufficient wind. It should be noted that the Wright 1905 Flyer (also called the Flyer III) flew more than 20 miles in October 1905, a full year before the 14-bis made its first flight.

The 14-bis was marginally controllable at best and could only make wallowing hops. This remained true after Santos-Dumont, who was on the right track, installed primitive ailerons in November 1906. Unfortunately, they proved ineffective. On the plus side, Santos-Dumont and other Europeans used wheels whereas the Wrights stuck with skids for too long, which necessitated the use of a catapult in the absence of significant wind.

Santos-Dumont fans usually infer that while the Wright Flyer may have been superior in the air, its take-off apparatus made it overly impractical to operate and transport. Alternatively, Wright brothers fans usually point to the implication that the scarcity of usable takeoff fields made the Flyer and "pillar" more practical, needing much less open, smooth and level space than the 14-bis.

Opinions may vary on whether the Wright Flyer or the 14-bis was the more practical (and thus the "first") heavier-than-air flying machine. Both designs produced aircraft that made free, manned, powered flights. Which one was "first" or "more practical" is a matter of how those words are defined. No one could contest that the Wrights flew first, that the Flyer was more capable in the air, or that Santos Dumont took off on wheels before the Wrights and earned a variety of prizes and official records in France. Patriotic pride heavily influences opinions of the relative importance and practicality of each aircraft, thus causing debate. U.S. citizens prefer definitions that make the Wrights the "first" to fly, while Brazilians believe that Santos Dumont had the first "real", practical airplane, and that his nationality may have caused his accomplishments to not receive worldwide recognition.

In subsequent years, Santos-Dumont built more aircraft like Demoiselle. He was so enthusiastic about aviation that he released the drawings of Demoiselle for free, thinking that aviation would be the mainstream of a new prosperous era for mankind, and it became the world's first series production aircraft.

Other early flights

Around the years 1900 to 1910, a number of other inventors made or claimed to have made short flights.

Lyman Gilmore claimed to have achieved success on 15 May 1902.

In New Zealand, South Canterbury farmer and inventor Richard Pearse constructed a monoplane aircraft that he reputedly flew in early 1903. Good evidence exists that on March 31, 1903 Pearse achieved a powered, though poorly controlled, flight of several hundred metres. Pearse himself said that although he had made a powered takeoff, it was at "too low a speed for [his] controls to work".

The first balloon flights took place in Australia in the late 1800s while Bill Wittber and then escapologist Harry Houdini made Australia's first controlled flights in 1910. [5]. Wittber was conducting taxiing tests in a Blériot XI aircraft in March 1910 in South Australia when he suddenly found himself about five feet in the air (Wittber's Hop). He flew about 40 feet (12 m) before landing. South Australia's other aviation firsts include the first flight from England to Australia by brothers Sir Ross and Sir Keith Smith in their Vickers Vimy bomber, the first Arctic flight by South Australian born Sir Hubert Wilkins and the first Australian born astronaut, Andy Thomas.

Karl Jatho from Hanover conducted a short motorized flight in August 1903, just a few months after Pearse. Jatho's wing design and airspeed did not allow his control surfaces to act properly to control the aircraft.

Also in the summer of 1903, eyewitnesses claimed to have seen Preston Watson make his initial flights at Errol, near Dundee in the east of Scotland. Once again, however, lack of photographic or documentary evidence makes the claim difficult to verify. Many claims of flight are complicated by the fact that many early flights were done at such low altitude that they did not clear the ground effect, and by the complexities involved in the differences between unpowered and powered aircraft.

The Wright brothers conducted numerous additional flights (about 150) in 1904 and 1905 from Huffman Prairie in Dayton, Ohio and invited friends and relatives. Newspaper reporters did not pay attention after seeing an unsuccessful flight attempt in May 1904.

Public exhibitions of high altitude flights were made by Daniel Maloney in the John Joseph Montgomery tandem-wing glider in March and April 1905 in the Santa Clara, California area. These flights received national media attention and demonstrated superior control of the design, with launches as high as 4,000 feet (1,200 m) and landings made at predetermined locations.

Two English inventors Henry Farman and John William Dunne were also working separately on powered flying machines. In January 1908, Farman won the Grand Prix d'Aviation by flying a 1 km circle, though by this time several longer flights had already been done. For example, the Wright brothers had made a flight over 39 km in October 1905. Dunne's early work was sponsored by the British military, and tested in great secrecy in Glen Tilt in the Scottish Highlands. His best early design, the D4, flew in December 1908 near Blair Atholl in Perthshire. Dunne's main contribution to early aviation was stability, which was a key problem with the planes designed by the Wright brothers and Samuel Cody.

On 14 May 1908 Wilbur Wright piloted the first two-person fixed-wing flight, with Charlie Furnas as a passenger.

On 8 July 1908 Thérèse Peltier became the first woman to fly as a passenger in an airplane when she made a flight of 656 feet (200 m) with Léon Delagrange in Milan, Italy.

Thomas Selfridge became the first person killed in a powered aircraft on 17 September 1908, when Orville Wright crashed his two-passenger plane during military tests at Fort Myer in Virginia.

The first powered flight in Britain was made in 1908 by American Sam Cody in a plane designed and built with the British Army.[23]

In September 1908, Mrs Edith Berg [24] became the first American woman to fly as a passenger in an airplane when she flew with Wilbur Wright in Le Mans, France.

The first powered flight by a Briton in Britain was made by John Moore-Brabazon (JTC Moore Brabazon) in May 1909 on the Isle of Sheppey (Kent).

On 25 July 1909 Louis Blériot flew the Blériot XI monoplane across the English Channel winning the Daily Mail aviation prize. His flight from Calais to Dover lasted 37 minutes.

On 22 October 1909 Raymonde de Laroche became the first woman to fly solo in a powered heavier -than-air craft. She was also the first woman in the world to receive a pilot's licence.

Controversy over who gets credit for invention of the aircraft has been fueled by Pearse's and Jatho's essentially non-existent efforts to inform the popular press and by the Wrights' secrecy while their patent was prepared. For example, the Romanian engineer Traian Vuia (1872–1950) has also been claimed to have built the first self-propelled, heavier-than-air aircraft able to take off autonomously, without a headwind and entirely driven by its own power. Vuia piloted the aircraft he designed and built on 18 March 1906 at Montesson, near Paris. None of his flights were longer than 100 feet (30 m) in length. In comparison, in October 1905, the Wright brothers had a sustained flight of 39 minutes and 24.5 miles (39 km), circling over Huffman Prairie.

Helicopter

In 1877, Enrico Forlanini developed an unmanned helicopter powered by a steam engine. It rose to a height of 13 meters, where it remained for some 20 seconds, after a vertical take-off from a park in Milan.

The first time a manned helicopter is known to have risen off the ground was in 1907 at Lisenux, France. The first successful rotorcraft, however, wasn't a true helicopter, but an autogyro invented by Spanish engineer Juan de la Cierva in 1919. These kind of rotorcrafts were mainly used until the development of modern helicopters, when, for some reason, they became largely neglected, although the idea has since been resurrected several times. Since the first practical helicopter was the Focke Achgelis Fw 61 (Germany, 1936), the autogyro's golden age only lasted around 20 years.

Seaplane

The first powered seaplane was invented in March 1910 by the French engineer Henri Fabre. Its name was Le Canard ('the duck'), and took off from the water and flew 800 meters on its first flight on March 28, 1910. These experiments were closely followed by the aircraft pioneers Gabriel and Charles Voisin, who purchased several of the Fabre floats and fitted them to their Canard Voisin airplane. In October 1910, the Canard Voisin became the first seaplane to fly over the river Seine, and in March 1912, the first seaplane to be used militarily from a seaplane carrier, La Foudre ('the lightning').

First performances steps under World War I (1914–1918)

Almost as soon as they were invented, planes were drafted for military service. The first country to use planes for military purposes was Italy, whose planes made reconnaissance, bombing and shelling correction military flights during the Italian-Turkish war (September 1911 – October 1912), in Libya. First mission (a reconnaissance) happened on the 23rd October 1911. First bombing of enemy columns was the 1st November 1911.[25] Then Bulgaria followed this example. Its planes attacked and reconnoitered the Ottoman positions during the First Balkan War 1912–13. The first war to see major use of planes in offensive, defensive and reconnaissance capabilities was World War I. The Allies and Central Powers both used planes extensively.

While the concept of using the aeroplane as a weapon of war was generally laughed at before World War I,[26] the idea of using it for photography was one that was not lost on any of the major forces. All of the major forces in Europe had light aircraft, typically derived from pre-war sporting designs, attached to their reconnaissance departments. Radiotelephones were also being explored on airplanes, notably the SCR-68, as communication between pilots and ground commander grew more and more important

Combat schemes

It was not long before aircraft were shooting at each other, but the lack of any sort of steady point for the gun was a problem. The French solved this problem when, in late 1914, Roland Garros attached a fixed machine gun to the front of his plane, but while Adolphe Pegoud would become known as the first "ace", getting credit for five victories, before also becoming the first ace to die in action, it was German Luftstreitkräfte Leutnant Kurt Wintgens, who, on July 1, 1915, scored the very first aerial victory by a purpose-built fighter plane, with a synchronized machine gun.

Aviators were styled as modern day knights, doing individual combat with their enemies. Several pilots became famous for their air to air combats, the most well known is Manfred von Richthofen, better known as the Red Baron, who shot down 80 planes in air to air combat with several different planes, the most celebrated of which was the Fokker Dr.I. On the Allied side, René Paul Fonck is credited with the most all-time victories at 75, even when later wars are considered.

Technology and performance advances in aviation's "Golden Age" (1918–1939)

The years between World War I and World War II saw great advancements in aircraft technology. Aeroplanes evolved from low-powered biplanes made from wood and fabric to sleek, high-powered monoplanes made of aluminum, based primarily on the founding work of Hugo Junkers during the World War I period. The age of the great airships came and went.

After WWI experienced fighter pilots were eager to show off their new skills. Many American pilots became barnstormers, flying into small towns across the country and showing off their flying abilities, as well as taking paying passengers for rides. Eventually the barnstormers grouped into more organized displays. Air shows sprang up around the country, with air races, acrobatic stunts, and feats of air superiority. The air races drove engine and airframe development—the Schneider Trophy, for example, led to a series of ever faster and sleeker monoplane designs culminating in the Supermarine S.6B, a direct forerunner of the Spitfire. With pilots competing for cash prizes, there was an incentive to go faster. Amelia Earhart was perhaps the most famous of those on the barnstorming/air show circuit. She was also the first female pilot to achieve records such as crossing of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

Other prizes, for distance and speed records, also drove development forwards. For example on June 14, 1919, Captain John Alcock and Lieutenant Arthur Brown co-piloted a Vickers Vimy non-stop from St. John's, Newfoundland to Clifden, Ireland, winning the £13,000 ($65,000)[27] Northcliffe prize. Eight years later Charles Lindbergh took the Orteig Prize of $25,000 for the first solo non-stop crossing of the Atlantic.

Australian Charles Kingsford Smith was the first to fly across the larger Pacific Ocean in the Southern Cross. His crew left Oakland, California to make the first trans-Pacific flight to Australia in three stages. The first (from Oakland to Hawaii) was 2,400 miles, took 27 hours 25 minutes and was uneventful. They then flew to Suva, Fiji 3,100 miles away, taking 34 hours 30 minutes. This was the toughest part of the journey as they flew through a massive lightning storm near the equator. They then flew on to Brisbane in 20 hours, where they landed on 9 June, 1928 after approximately 7,400 miles total flight. On arrival, Kingsford Smith was met by a huge crowd of 25,000 at Eagle Farm Airport in his hometown of Brisbane. Accompanying him were Australian aviator Charles Ulm as the relief pilot, and the Americans James Warner and Captain Harry Lyon (who were the radio operator, navigator and engineer). With Ulm, Kingsford Smith later continued his journey being the first in 1929 to circumnavigate the world, crossing the equator twice.

The first lighter-than-air crossings of the Atlantic were made by airship in July 1919 by His Majesty's Airship R34 and crew when they flew from East Lothian, Scotland to Long Island, New York and then back to Pulham, England. By 1929, airship technology had advanced to the point that the first round-the-world flight was completed by the Graf Zeppelin in September and in October, the same aircraft inaugurated the first commercial transatlantic service. However the age of the dirigible ended following the destruction by fire of the zeppelin Hindenburg just before landing at Lakehurst, New Jersey on May 6, 1937, killing 35 of the 97 people aboard. Previous spectacular airship accidents, from the Wingfoot Express disaster (1919) to the loss of the Akron (1933) and the Macon (1935) had already cast doubt on airship safety; following the destruction of the Hindenburg, the remaining airship making international flights, the Graf Zeppelin was retired (June 1937); its replacement, the dirigible Graf Zeppelin II, made a number of flights, primarily over Germany, from 1938 to 1939, but was grounded when Germany began World War II. Both remaining German zeppelins were scrapped in 1940 to supply metal for the German Luftwaffe; the last American zeppelin, the Los Angeles, which had not flown since 1932, was dismantled in late 1939.

Meanwhile in Germany, who was restricted by the Treaty of Versailles in its development of powered aircraft, instead developed gliding as a sport, especially at the Wasserkuppe, during the 1920s. In its various forms, this activity now has over 400,000 participants.[28][29]

In 1929 Jimmy Doolittle developed instrument flight.

1929 also saw the first flight of by far the largest plane ever built until then: the Dornier Do X with a wing span of 48 m. On its 70th test flight on October 21 there were 169 people on board, a record that was not broken for 20 years.

In the 1930s development of the jet engine began in Germany and in England. In England Frank Whittle patented a design for a jet engine in 1930 and towards the end of the decade began developing an engine. In Germany Hans von Ohain patented his version of a jet engine in 1936 and began developing a similar engine. The two men were unaware of the other's work, and both Germany and Britain would go on to develop jet aircraft by the end of World War II.

Progress goes on and massive production, World War II (1939–1945)

World War II saw a drastic increase in the pace of aircraft development and production. All countries involved in the war stepped up development and production of aircraft and flight based weapon delivery systems, such as the first long range bomber. Also air combat tactics and doctrines changed, large scale strategic bombing campaigns were launched, Fighter escorts introduced and the more flexible aircraft and weapons allowed more precise attacks on small targets for effective ground support (see: dive bomber). New technologies like radar also allowed more coordinated and controlled deployment of fighter aircraft.

The first functional jetplane was the Heinkel He 178 (Germany), flown by Erich Warsitz in 1939 (a Coanda-1910 is said to have done a short involuntary flight on December 16, 1910), followed by the worlds first operational fighter aircraft, the Me 262, in July 1942 and worlds first jet powered bomber, the Arado Ar 234, in June 1943. British developments, like the Gloster Meteor, followed afterwards, but saw only brief use in World War II. The first cruise missile (V-1), the first ballistic missile (V-2), the first (and to date only) operational rocket powered combat aircraft Me 163 and the first vertical take-off manned point-defense interceptor Bachem Ba 349 were also developed by Germany. However, jet fighters had only limited impact due to their late introduction, fuel shortages, the lack of experienced pilots and the declining war industry of Germany.

But not only airplanes, helicopters too saw rapid development in the Second World War. With the introduction of the Focke Achgelis Fa 223, the Flettner Fl 282 in 1941 in Germany and the Sikorsky R-4 1942 in the USA, the first time larger helicopter formations were produced and deployed.

1945–1991: The Cold War

After World War II, commercial aviation grew rapidly, used mostly ex-military aircraft to transport people and cargo. This growth was accelerated by the glut of heavy and super-heavy bomber airframes like the B-29 and Lancaster that could be converted into commercial aircraft. The DC-3 also made for easier and longer commercial flights. The first commercial jet airliner to fly was the British De Havilland Comet. By 1952, the British state airline BOAC had introduced the De Havilland Comet into scheduled service. While a technical achievement, the plane suffered a series of highly public failures, as the shape of the windows led to cracks due to metal fatigue. The fatigue was caused by cycles of pressurization and depressurization of the cabin, and eventually led to catastrophic failure of the plane's fuselage. By the time the problems were overcome, other jet airliner designs had already taken to the skies.

USSR's Aeroflot became the first airline in the world to operate sustained regular jet services on September 15, 1956 with the Tupolev Tu-104. Boeing 707, which established new levels of comfort, safety and passenger expectations, ushered in the age of mass commercial air travel, dubbed the Jet Age.

In October 1947 Chuck Yeager took the rocket powered Bell X-1 past the speed of sound. Although anecdotal evidence exists that some fighter pilots may have done so while divebombing ground targets during the war, this was the first controlled, level flight to cross the sound barrier. Further barriers of distance fell in 1948 and 1952 with the first jet crossing of the Atlantic and the first nonstop flight to Australia.

When the Soviet Union developed long-range bombers that could deliver nuclear weapons to North America and Europe, Western countries responded with interceptor aircraft that could engage and destroy the bombers before they reached their destination. The "minister-of-everything" C.D. Howe in the Canadian government, was the key proponent of the Avro Arrow, designed as a high-speed interceptor, reputedly the fastest aircraft in its time. However, by 1955, most Western countries agreed that the interceptor age was replaced by guided missile age. Consequently, the Avro Arrow project was eventually cancelled in 1959 under Prime Minister John Diefenbaker. See Avro Arrow for more details.

In 1961, the sky was no longer the limit for manned flight, as Yuri Gagarin orbited once around the planet within 108 minutes, and then used the descent module of Vostok I to safely reenter the atmosphere and reduce speed from Mach 25 using friction and converting velocity into heat. This action further heated up the space race that had started in 1957 with the launch of Sputnik 1 by the Soviet Union. The United States responded by launching Alan Shepard into space on a suborbital flight in a Mercury space capsule. With the launch of the Alouette I in 1963, Canada became the third country to send a satellite in space. The Space race between the United States and the Soviet Union would ultimately lead to the landing of men on the moon in 1969.

In 1967, the X-15 set the air speed record for an aircraft at 4,534 mph (7,297 km/h) or Mach 6.1 (7,297 km/h). Aside from vehicles designed to fly in outer space, this record was renewed by X-43 in the 21st century.

The Harrier Jump Jet, often referred to as just "Harrier" or "the Jump Jet", is a British designed military jet aircraft capable of Vertical/Short Takeoff and Landing (V/STOL) via thrust vectoring. It first flew in 1969. The same year that Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin set foot on the moon, and Boeing unveiled the Boeing 747 and the Aérospatiale-BAC Concorde supersonic passenger airliner had its maiden flight. The 747 plane was the largest aircraft ever to fly, and still carries millions of passengers each year, though it has been superseded by the Airbus A380, which is capable of carrying up to 853 passengers. In 1975 Aeroflot started regular service on Tu-144—the first supersonic passenger plane. In 1976 British Airways began supersonic service across the Atlantic, with Concorde. A few years earlier the SR-71 Blackbird had set the record for crossing the Atlantic in under 2 hours, and Concorde followed in its footsteps.

The last quarter of the 20th century saw a slowing of the pace of advancement. No longer was revolutionary progress made in flight speeds, distances and technology. This part of the century saw the steady improvement of flight avionics, and a few minor milestones in flight progress.

For example, in 1979 the Gossamer Albatross became the first human powered aircraft to cross the English channel. This achievement finally saw the realization of centuries of dreams of human flight. In 1981, the Space Shuttle made its first orbital flight, proving that a large rocket ship can take off into space, provide a pressurised life support system for several days, reenter the atmosphere at orbital speed, precision glide to a runway and land like a plane.

In 1986 Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager flew an aircraft, the Rutan Voyager, around the world unrefuelled, and without landing. In 1999 Bertrand Piccard became the first person to circle the earth in a balloon. Focus was turning to the ultimate conquest of space and flight at faster than the speed of sound. The ANSARI X PRIZE inspired entrepreneurs and space enthusiasts to build their own rocket ships to fly faster than sound and climb into the lower reaches of space.

2001–present

In the beginning of the 21st century, subsonic military aviation focused on eliminating the pilot in favor of remotely operated or completely autonomous vehicles. Several unmanned aerial vehicles or UAVs have been developed. In April 2001 the unmanned aircraft Global Hawk flew from Edwards AFB in the US to Australia non-stop and unrefuelled. This is the longest point-to-point flight ever undertaken by an unmanned aircraft, and took 23 hours and 23 minutes. In October 2003 the first totally autonomous flight across the Atlantic by a computer-controlled model aircraft occurred.

In commercial aviation, the early 21st century saw the end of an era with the retirement of Concorde. Supersonic flight was not commercially viable, as the planes were required to fly over the oceans if they wanted to break the sound barrier. Concorde also was fuel hungry and could carry a limited amount of passengers due to its highly streamlined design. Nevertherless, it seems to have made a significant operating profit for British Airways.

The U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission was established in 1999 to encourage the broadest national and international participation in the celebration of 100 years of powered flight.[30] It publicized and encouraged a number of programs, projects and events intended to educate people about the history of aviation.

Major disruptions to air travel in the 21st Century included the closing of U.S. airspace due to the September 11 attacks, and the closing of northern European airspace after the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajökull.

See also

References

- ^ a b Crouch, Tom (2004), Wings: A History of Aviation from Kites to the Space Age, New York: W.W. Norton & Co, ISBN 0393326209

- ^ Brown, Brian (1922), Chinese Nights Entertainments, Brentano's, OCLC 843525

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=PehoSnJfstUC&pg=PA285&lpg=PA285&dq=Yuan+Huangtou&source=bl&ots=Tp18nnOIZG&sig=96izx1JEKzdNsyAHyR39nEFtcbY&hl=en&ei=TmQbTO7qCcSrca_4uZUK&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=7&ved=0CCkQ6AEwBg#v=onepage&q=Yuan%20Huangtou&f=false

- ^ Darling, David J. (2002), The complete book of spaceflight, John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 9780471056492, retrieved 2009-06-28

- ^ Gellius, Aulus (1795), The Attic nights of Aulus Gellius, J. Johnson

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Archytas of Tarentum, Technology Museum of Thessaloniki, Macedonia, Greece, retrieved 2009-06-27

- ^ Howe, Henry (1858), Memoirs of the most eminent American mechanics, Derby & Jackson

- ^ Wise, John (1850), A System of Aeronautics, Comprehending Its Earliest Investigations.., J.A. Speel

- ^

Yinke Deng and Pingxing Wang (2005), Ancient Chinese Inventions, p. 113, ISBN ISBN 7-5085-0837-8

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Lynn Townsend White, Jr. (Spring, 1961). "Eilmer of Malmesbury, an Eleventh Century Aviator: A Case Study of Technological Innovation, Its Context and Tradition", Technology and Culture 2 (2), p. 97–111 [100–101].

- ^ First Flights, Saudi Aramco World, January–February 1964, p. 8–9.

- ^ a b c d Lynn Townsend White, Jr. (Spring, 1961). "Eilmer of Malmesbury, an Eleventh Century Aviator: A Case Study of Technological Innovation, Its Context and Tradition", Technology and Culture 2 (2), p. 97-111 [100f.] Cite error: The named reference "Lynn White 1961, 100f." was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ White 1961, p. 98

- ^ Dreams of Leonardo, program by Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), October 2005, describes the building and successful flight of a glider based on Leonardo's design

- ^ Frank H. Wenham, inventor of the wind tunnel, 1871, was a fan, driven by a steam engine, propelled air down a 12 ft (3.7 m). (3.7 m) tube to the model. NASA: [1]

- ^ Gustav Weisskopf—Geschichte des 1.Motorflugs der Welt 1901

- ^ Dodson, MG (2005), "An Historical and Applied Aerodynamic Study of the Wright Brothers' Wind Tunnel Test Program and Application to Successful Manned Flight", US Naval Academy Technical Report, USNA-334, retrieved 2009-03-11

- ^ Smithsonian Institution, "The Wright Brothers & The Invention of the Aerial Age"

- ^ " 100 Years Ago, the Dream of Icarus Became Reality." FAI NEWS, December 17, 2003. Retrieved: January 5, 2007.

- ^ Kelly, Fred C. The Wright Brothers: A Biography Chp. IV, p.101–102 (Dover Publications, NY 1943).

- ^ Dayton Metro Library Aero Club of America press release

- ^ Reprinted in Scientific American, April 2007, page 8.

- ^ "First powered flight's centenary", BBC News, October 16, 2008, retrieved March 31, 2010

- ^ [2]

- ^ Ferdinando Pedriali. "Aerei italiani in Libia (1911–1912)"(Italian planes in Libya (1911–1912)). Storia Militare (Military History), N° 170/novembre 2007,p.31–40

- ^ with the exception of Clément Ader, who had visionary views about that : "L'affaire de l'aviation militaire"(Military aviation concern), 1898 and "La première étape de l'aviation militaire en France" (The first step of military aviation en France), 1906

- ^ Nevin, David. "Two Daring Flyers Beat the Atlantic before Lindbergh." Journal of Contemporary History' 28: (1) 1993, 105.

- ^ FAI membership summary, retrieved 2006-08-24

- ^ FAI web site

- ^ Executive Summary, U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission

Further reading

- * Jourdain, Pierre-Roger (1908), "Aviation In Frances In 1908", Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution: 145–159, retrieved 2009-08-07

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Post, Augustus (1910), "How To Learn To Fly: The Different Machines And What They Cost", The World's Work: A History of Our Time, XX: 13389–13402

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|title=|month=ignored (help) Includes photos, diagrams and specifications of many c. 1910 aircraft. - Squier, George Owen (1908), "The Present Status of Military Aeronautics.", Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution: 117–144, retrieved 2009-08-07

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) Includes photos and specifics of many c. 1908 dirigibles and aeroplanes.

External links

- http://www.flyingmachines.org/

- http://www.thewrightbrothers.org/fivefirstflights.html

- Time line of greatest breakthroughs in manned flight by Jürgen Schmidhuber, Nature 421, 689, 2003

- Prehistory of Flight

- Graphic time-line

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections—Transportation Photographs An ongoing digital collection of photographs depicting various modes of transportation in the Pacific Northwest region and Western United States during the first half of the 20th century.

- Aviation research at the National Archives—how to find aviation photos and records.

- Aviation: From Sand Dunes to Sonic Booms, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- Aviation history article.

- Aviation History at Muswell Manor

- Film trailer of A Dream of Flight a documentary that celebrates the centenary of the first powered flight by a Briton in Britain, JTC Moore Brabazon, in 1909 on The Isle of Sheppey.

- Wright Brothers' Early Flight Experiments